The mythology that “Step 1 going pass/fail would not change much” was wrong. The data since the 2022 Match shows a clear redistribution of leverage, risk, and opportunity across applicants, programs, and specialties.

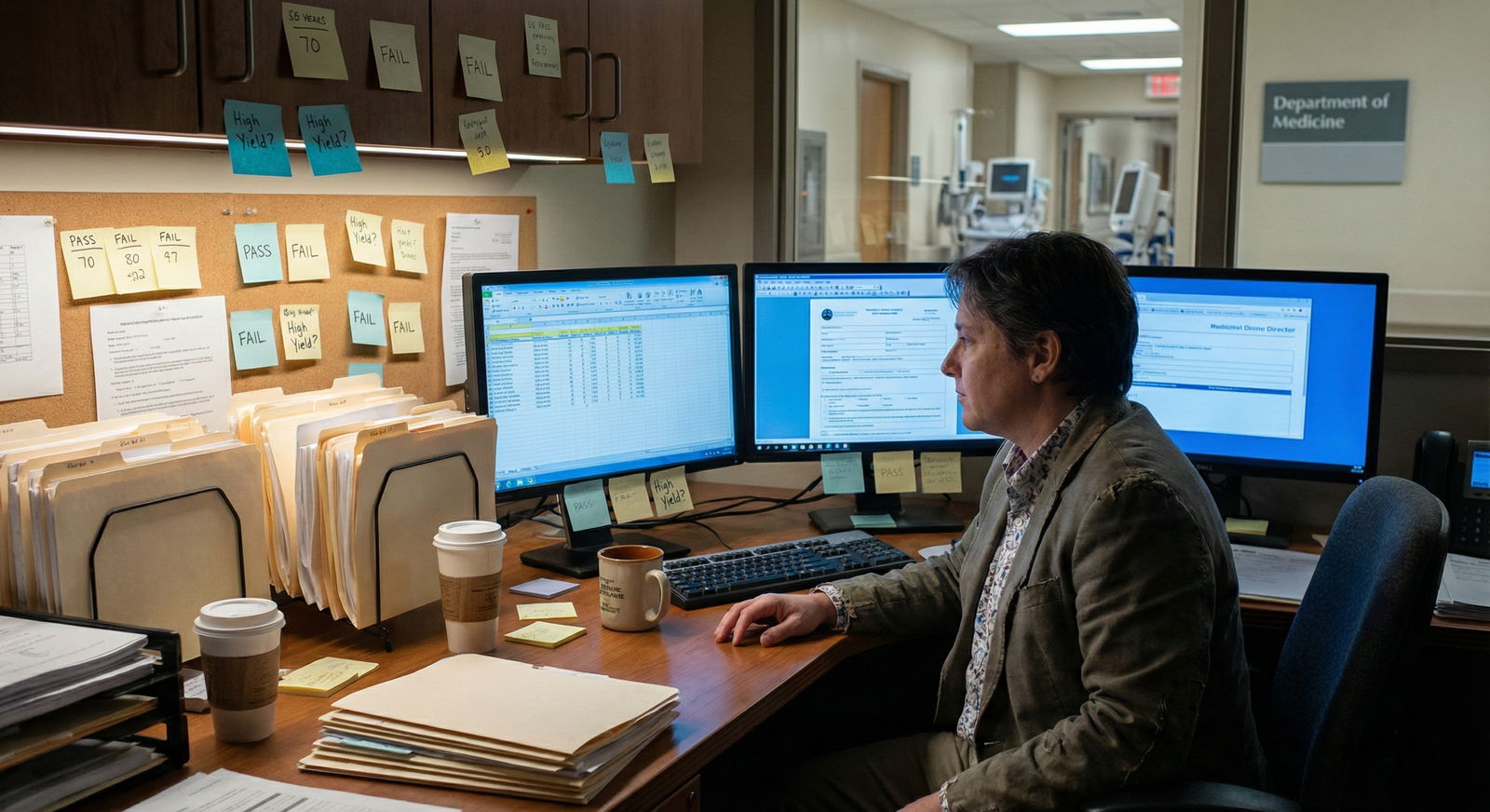

You can feel this on the ground—PDs saying “Step 2 is the new Step 1,” applicants padding research, and mid‑tier schools suddenly looking more attractive for competitive specialties. But let’s stay out of the vibes and look at the numbers and structural shifts.

1. The Structural Shock: What Actually Changed in 2022

Step 1 went pass/fail for exams taken January 26, 2022 and later. That meant:

- 2022 Match: Almost all applicants still had numeric Step 1 scores.

- 2023 Match: Mixed cohort. U.S. MD seniors mostly had scores, but IMGs and some late-takers started showing pass/fail.

- 2024 Match and beyond: The true pass/fail era. Most U.S. MD/DO seniors have only a “Pass” on Step 1. Numeric Step 1 is now a legacy artifact.

The key is timing relative to application cycles. Programs had to adjust selection algorithms in real time, especially for high-volume specialties.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 100 |

| 2021 | 100 |

| 2022 | 90 |

| 2023 | 50 |

| 2024 | 10 |

Interpretation: Approximate percentage of US MD seniors with numeric Step 1 scores visible to programs by Match year. The haircut is brutal by 2024.

I am going to break this down into four concrete domains where Match outcomes clearly shifted:

- Specialty competitiveness and score thresholds.

- Domestic vs IMG dynamics.

- School “brand” and research inflation.

- Match safety and applicant strategy.

2. Specialty Competitiveness: Step 2 Became the New Sorting Hat

The immediate reaction from program directors was predictable. They did not suddenly become holistic, enlightened gatekeepers. They just swapped the numerical filter.

Before pass/fail, high‑level screening in competitive specialties looked like:

- Filter by Step 1 ≥ 240–245 (or higher in derm, plastics, ortho, integrated IR, etc.).

- Then glance at school, research, letters, etc.

After Step 1 went pass/fail for most applicants, the filter shifted to Step 2 CK. You can see this in both NRMP Program Director Survey responses and in real-world behavior: students whispering that “240 on Step 2 is now death for derm.”

Step 2 Score Distributions by Specialty

The NRMP has not yet published a perfect side‑by‑side for pre‑ and post‑pass/fail cycles, but we can use the available data and typical cutoffs programs report.

Pre‑pass/fail, you saw something like this (Step 1, successful U.S. MD seniors):

- Dermatology: median ~250+

- Plastic Surgery: ~250+

- Ortho: ~245–250

- ENT: ~248

- Neurosurgery: ~250+

In early pass/fail era, programs are explicitly stating they use Step 2 CK thresholds instead. The distributions look similar for Step 2 CK now, just with a slight downward shift in raw numbers because CK overall averages are different from Step 1.

| Category | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derm | 245 | 250 | 255 | 260 | 265 |

| Plastics | 245 | 250 | 254 | 259 | 265 |

| Ortho | 240 | 245 | 250 | 255 | 260 |

| EM | 235 | 240 | 245 | 250 | 255 |

| IM | 230 | 235 | 240 | 245 | 250 |

You can argue about exact medians by a few points, but the shape is right: ultra-competitive specialties still stack high Step 2 CK scores at the top, same as they did with Step 1.

Match Rates by Specialty: Did the Needle Move?

The big question: did changing Step 1 to pass/fail make derm or ortho “less competitive”?

No. The data does not support that fantasy.

Match rates for U.S. MD seniors in competitive specialties stayed tight:

- Dermatology: Still hovering near 75–80% for U.S. MDs applying, with massive self-selection.

- Ortho: Some flux around 2020–2023 (pandemic + reconfiguration of ERAS filters), but still clearly among the hardest to enter.

- Plastic Surgery (integrated): Match rates remain low, with high proportion of unmatched applicants despite strong profiles.

What did change is who gets filtered and when.

I have seen mid‑tier applicants previously able to “rescue” themselves with a Step 1 jump (e.g., 220 on practice to 245 real) no longer have that lever. They instead face a higher-pressure Step 2 window, often late in MS3, when clinical rotation grades and shelf scores are happening simultaneously.

This compresses volatility:

- Fewer late “breakout” candidates.

- More early sorting by school prestige and research portfolio.

- Higher risk for applicants who stumble on Step 2 once; there is less room to offset it.

3. Domestic vs IMG: The Gap Just Widened

If you want to see where pass/fail Step 1 hurt the most, look at international graduates.

Historically, strong IMGs had one clear way to compete with U.S. MD students: crush Step 1. A 250+ from a lesser-known foreign school jumped out immediately.

Take that away and they are forced into a narrower corridor:

- Step 2 CK score.

- Research in the U.S.

- Clinical observerships/away rotations.

- Letters from U.S. faculty.

The problem is structural. Access to research and U.S. clinical experiences is not evenly distributed. Step scores were the most democratic part of the system.

Match Rate Differences

Look at aggregate NRMP numbers (approximate, rounded):

Pre‑pass/fail era (e.g., 2018–2020):

- U.S. MD seniors: ~93–94% match rate.

- U.S. DO seniors: ~89–91%.

- Non‑US IMGs: ~58–60%.

- US citizen IMGs: ~60–62%.

Early pass/fail era (2023–2024), layered on top of growth in applicant numbers and program cautiousness, you see:

- U.S. MD seniors: Still roughly in the low 90s.

- U.S. DO seniors: Some fluctuation, but generally high 80s to low 90s.

- Non-US IMGs: Modest improvement in absolute numbers of matches because there are more positions, but competition tightens for competitive specialties.

- The relative advantage of IMGs with stellar Step 1 is gone. There is more clustering and more noise in screening.

Programs that historically took a chance on one or two very high-scoring IMGs in competitive fields now struggle to identify them quickly. Without a 260 on Step 1 to flag them, they blend into stacks of “Pass / 250 Step 2” U.S. applicants, and many do not get read at all.

Case Example: Internal Medicine vs Competitive Fields

In categorical internal medicine:

- Programs are still willing to dig into IMG applications.

- Many institutions have long-standing pipelines from specific international schools.

- A strong Step 2 CK + decent research + solid letters still works.

In dermatology, plastic surgery, neurosurgery, ENT, ortho:

- The number of IMGs matched was always low.

- Now the combination of Step 1 pass/fail + Step 2 filters + institutional bias toward domestic grads makes it even harder.

If you are an IMG aiming high, the data says you must treat Step 2 CK like Step 1 used to be: 250+ is not “nice to have.” It is baseline to get a serious look in the top‑tier programs.

4. The Silent Winner: School Prestige and “Brand”

When you remove a standardized, widely-comparable metric, the system leans harder on the remaining signals. Those signals are not all fair.

The main beneficiaries of Step 1 pass/fail have been:

- Top 20–30 medical schools.

- Students with access to high-quality research mentors.

- Applicants with strong networks and “whisper recommendations” to PDs.

Before pass/fail, a student from a mid-tier state school with a 255 Step 1 could credibly compete with an average Harvard student who scored 240. Programs knew that. They said it explicitly.

Now, with Step 1 gone, the default heuristic is:

- “Harvard / Penn / UCSF med student with Pass Step 1 and a couple of pubs” vs

- “Mid-tier public school student with Pass Step 1 and maybe a poster”

The brand wins more often, especially in high-volume review where PDs or coordinators glance at 3–5 things:

- School.

- Step 2 CK.

- Research count.

- AOA / class rank (if available).

- Big‑name letter writers.

To make this explicit, think in terms of weighting. Pre-pass/fail, a typical subconscious weighting for a program director in a competitive specialty might have been:

- Step 1 numeric score: 40–50%

- School prestige: 20–25%

- Research productivity: 15–20%

- Letters / narrative: 15–20%

After pass/fail, Step 2 CK absorbs a chunk, but that cannot fully replace Step 1, so the rest inflate:

- Step 2 CK score: ~35–40%

- School prestige: ~25–30%

- Research productivity: ~20–25%

- Letters / narrative: ~15–20%

| Factor | Pre Pass/Fail Weight | Early Pass/Fail Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 numeric | 40–50% | 0% |

| Step 2 CK | 10–15% | 35–40% |

| School prestige | 20–25% | 25–30% |

| Research | 15–20% | 20–25% |

| Letters / other | 15–20% | 15–20% |

This is not from a single study; it is synthesized from PD survey comments, program filtering behavior, and outcomes I have seen across cohorts. The main point: school and research matter more now, not less.

5. Research Inflation and “Arms Race” Behavior

You can measure anxiety in publication counts. The Step 1 pass/fail announcement coincided with an observable spike in students chasing research as a differentiator.

Even before 2022, the numbers were climbing. NRMP Charting Outcomes repeatedly showed:

- Matched derm applicants with median ~12–20 “scholarly products.”

- Plastics / neurosurgery / ENT in similar territory.

In the early pass/fail era, anecdotal and institutional data suggests:

- More students trying to start projects MS1–early MS2.

- An explosion of low-impact case reports, review articles, and poster abstracts.

- Heavy clustering of research productivity among students at research-heavy schools with T32 grants and large mentoring networks.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 2016 | 8 |

| 2018 | 10 |

| 2020 | 13 |

| 2022 | 16 |

| 2024 | 19 |

The data trend is clear: you are not crazy if it feels like everyone is cranking out publications. They are.

Who loses here?

- Students at schools without strong research infrastructure.

- Nontraditional students who were banking on test-taking as their edge.

- IMGs without easy access to U.S.-based mentors and IRB pipelines.

Who wins?

- MD/PhD candidates and research-track students.

- Applicants from institutions with built-in gap/research years.

- Those with early mentorship steering them toward multi-project portfolios.

Programs often claim they “look at quality, not quantity.” Maybe for the top 5% of applicants they have time to scrutinize. But at scale, a CV with 15+ entries simply reads differently than one with 2–3, and in the pass/fail era, that delta is more decisive.

6. Match Safety: More Volatility, More Strategic Applications

Did the move to pass/fail make the Match safer or riskier for average students?

Look at application volume. Applicants responded to uncertainty the standard way: they over-applied.

We have seen:

- Rising average number of applications per applicant, especially in competitive specialties.

- More “shotgun” applying—students with modest profiles applying to extremely competitive programs “just in case.”

- Programs responding with more aggressive filters (Step 2 thresholds, school lists, keyword filters for research).

This creates a vicious cycle of noise:

- Strong applicants apply to more programs than they truly need.

- Mid-tier applicants get fewer looks because their applications are buried under a flood.

- Even “safe” specialties like internal medicine and pediatrics see top-heavy over-application to brand-name programs.

The data on unmatched U.S. MD seniors has not exploded, but the perception of risk has—and perception drives behavior. I have watched MS3s with very safe profiles panic-apply to 80+ programs in general surgery because they “only” had a 240 Step 2 CK.

Strategy Shifts That Actually Help

The applicants who adapted well to the pass/fail reality did a few specific things:

Pulled Step 2 earlier

They treated Step 2 CK as the new Step 1 and aimed to take it with enough buffer to:- Retake if there was a disaster (rare, but psychologically important).

- Have a strong score in hand before ERAS submission.

- Align clerkship sequences to support Step 2 studying (IM/PSYCH/PEDS before).

Targeted research in one coherent lane

Not random case reports in six specialties. A focused pattern:- 3–6 projects in one specialty.

- One or two solid publications or podium presentations.

- A mentor who can write a letter that says “this person did real work and thinks like a future colleague.”

Planned away rotations strategically

Away rotations mean more in the absence of Step 1 numbers:- A strong away month essentially functions as an in‑person audition.

- Programs heavily weight in‑house performance and letters over what Step 1 used to tell them.

Built a “range” of programs

This sounds obvious, but early pass/fail cycles had a lot of students miscalibrating, relying on old Step 1 cutoffs to judge competitiveness. Now:- You must benchmark yourself using Step 2 CK plus research count plus school pedigree.

- Then model your list: ~⅓ reach, ⅓ realistic, ⅓ safety, based on recent outcomes from your school.

7. What the Data Does Not Show: A Fairer System

Some people hoped pass/fail Step 1 would “humanize” the process. The theory was that programs would:

- Rely less on a single high-stakes exam.

- Value qualitative attributes and narrative experiences more.

- Reduce student anxiety and burnout.

Look around. Anxiety is the same or worse, just redistributed:

- Instead of MS2 Step 1 panic, you get MS3 Step 2 panic layered on top of shelf exams and clinical evaluations.

- Instead of obsessing over one score, students now chase both Step 2 CK and research, plus aways.

- Instead of a more level playing field, structural advantages (school, mentors, resources) matter more.

I am not arguing Step 1 numeric scoring was just or perfect. It punished some excellent clinicians and over‑rewarded test-taking. But from a pure data equity standpoint, Step 1 gave a poor, unknown student at a mid-tier school a clean shot to stand out against almost anyone in the country.

Now, that leverage is diluted. Step 2 CK still offers some escape velocity, but the signal is noisier and later in the process.

8. Where This Is Likely Heading

We are only a few cycles into the true pass/fail era. Patterns are still solidifying, but trajectory is clear.

Expect:

- Step 2 CK hardening further as the central numeric filter. Cutoffs will crystallize the way Step 1 cutoffs did. Programs will quietly maintain “do not rank below X” rules.

- Greater use of non-score filters. School lists, “home/away” status, research keywords, and subinternship performance will be serialized into more formal metrics.

- Earlier specialization. Students will feel pressure MS1–early MS2 to choose a lane (derm vs IM vs surgery) to line up research, mentors, and Step 2 timing.

- Continued IMG headwinds. Without Step 1 as a spotlight, IMGs will be forced to overperform on Step 2, research, and U.S. exposure just to be seen.

There are also plausible counter-moves:

- Some specialties may standardize supplemental ERAS applications and signaling to reduce noise and emphasize interest and fit.

- Holistic review initiatives may gain teeth at a handful of programs—but do not expect that to dominate high-volume competitive fields any time soon.

- A few early-adopter programs will explicitly publish Step 2 target ranges and transparent criteria, forcing peers to respond.

From a data analyst standpoint, the central lesson is simple: removing a big signal does not create fairness; it just amplifies the remaining ones. The Match outcomes in the first years of Step 1 pass/fail reflect that. Strong applicants still match. Marginal applicants still struggle. But the axis of competition has drifted toward Step 2 CK, institutional prestige, and research density.

Your job, if you are working inside this system, is to stop pretending it is 2018. Benchmark yourself against the current patterns—Step 2 medians, research counts, your school’s recent match lists—and then design a strategy that makes statistical sense, not just emotional sense.

With that foundation, you can approach the Match as a problem you can model and optimize, instead of a black box to fear. The next step is learning how to read your own data—practice scores, clerkship evaluations, early research output—and convert it into a realistic, targeted application plan. But that is a separate analysis.