Mastering Your Observership: How IMGs Can Shine in U.S. Clinical Settings

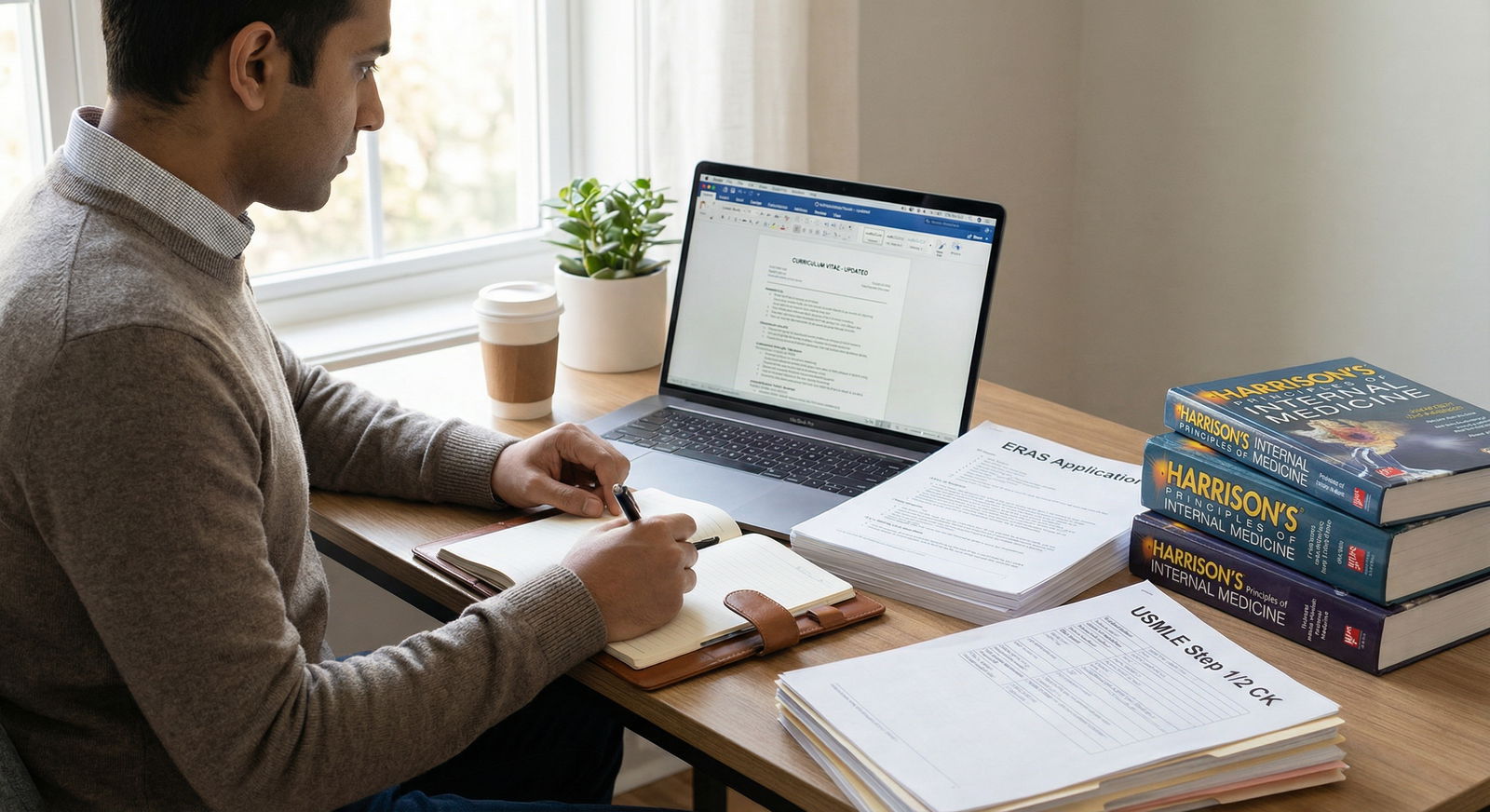

Observerships are one of the most important early steps International Medical Graduates (IMGs) can take on the journey toward a successful U.S. residency application. While they do not involve direct patient care, a well-chosen and well-executed observership can significantly strengthen your profile, expand your professional network, and deepen your understanding of the American healthcare system.

This expanded guide goes beyond the basics to help you not only “get through” an observership, but truly master it—transforming a short-term experience into long-term career value in medical education and clinical practice.

Understanding Observerships for International Medical Graduates

What Is an Observership?

An observership is a structured, non-clinical, unpaid experience in which an IMG or medical student observes patient care, clinical workflows, and healthcare team dynamics within a U.S. hospital or clinic. Unlike hands-on clinical electives, observers do not independently examine patients, write notes, or enter orders. Instead, you:

- Shadow attending physicians, residents, or fellows

- Watch patient encounters and procedures (with patient permission)

- Learn how care teams communicate and make decisions

- Familiarize yourself with U.S. medical documentation and systems

For many IMGs, observerships are the first real exposure to the U.S. healthcare environment—its expectations, pace, culture, and professional norms.

Observerships vs. Other U.S. Clinical Experiences

It is important to distinguish observerships from other types of U.S. clinical experience (USCE):

Observership

- Non-clinical; observation only

- Often for IMGs who have already graduated

- No direct patient care or documentation

- Valuable for healthcare networking and system familiarity

Externship

- May include limited supervised hands-on tasks

- Sometimes allows documentation or basic procedures

- Often geared toward demonstrating clinical skills

Elective / Sub-internship (for current students)

- Hands-on clinical role with defined responsibilities

- Strongest form of USCE for residency applications

Even if observerships are less “hands-on,” they can still be powerful components of your residency application when you approach them strategically.

Why Institutions Offer Observerships

Understanding the institution’s perspective will help you align your behavior with their expectations. Institutions typically offer observerships to:

- Support global medical education and international collaboration

- Identify potential residency candidates early

- Build diverse, culturally competent care environments

- Contribute to professional development for IMGs

When you act like a motivated future colleague rather than a passive observer, you fit exactly what these programs hope to achieve.

Why a Strong Observership Matters for Your Residency Application

A thoughtfully selected and well-executed observership can impact multiple parts of your residency journey.

1. Strengthening Your Residency Application Profile

Programs increasingly look for evidence that an IMG understands U.S. healthcare culture and expectations. A strong observership can:

Boost your CV

- Lists as U.S. clinical experience under "Observerships"

- Shows specialty alignment (e.g., cardiology observership for internal medicine applications)

- Demonstrates initiative to learn beyond your home country

Improve your personal statement

- Real patient scenarios and reflections demonstrate insight

- Clear examples of growth in communication, professionalism, or systems-based practice

Support interview performance

- You can answer questions with concrete U.S.-based examples

- Shows that your interest in the specialty is based on first-hand exposure

2. Building a Strategic Healthcare Network

Healthcare networking is one of the most underestimated benefits of an observership. Through daily interactions, you can:

- Meet attendings and fellows who may later advocate for you

- Connect with residents who recently navigated the Match

- Learn about research, quality improvement, or teaching opportunities

- Receive informal advice on programs, regions, and strategies for IMGs

When nurtured thoughtfully, connections you make during a four-week observership can influence your career for years.

3. Earning Strong Letters of Recommendation

Some observership programs allow attendings to provide letters of recommendation (LoRs) if:

- You attend regularly and on time

- You are engaged, prepared, and professional

- You show evidence of growth, insight, and reliability

These LoRs may explicitly state the nature and limits of your role (observer vs. hands-on), but they still carry weight—especially if the letter writer is well-known in the specialty or within a residency program.

4. Developing Critical Soft Skills

Beyond clinical knowledge, observerships help you:

- Refine medical English in real clinical conversations

- Learn how to communicate concisely with busy teams

- Experience interprofessional collaboration among physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and others

- Become more comfortable with U.S. cultural norms around professionalism, hierarchy, consent, and patient autonomy

These soft skills are major differentiators for IMGs in residency interviews and during intern year.

Preparing for Your Observership: Before Day One

Thorough preparation is what separates a routine observership from an exceptional one. Preparation shows respect for the institution and maximizes your learning.

Researching the Institution and Department

Go beyond the hospital’s homepage. Before you start:

Study the institution

- Mission, values, patient population

- Teaching hospital vs. community setting

- Affiliation with a medical school or residency program

Learn about the department

- Clinical services and subspecialty clinics

- Types of patients commonly seen (e.g., oncology, trauma, cardiac)

- Academic strengths (e.g., strong in research, quality improvement, medical education)

Review physician profiles

- Training background and subspecialty interests

- Recent publications or ongoing research

- Leadership roles (program director, clerkship director, chief of service)

Use this knowledge to ask informed questions, show genuine interest, and target your discussions (e.g., “I read your paper on heart failure readmissions and was curious about…”).

Setting Clear, Measurable Goals

Arrive with concrete goals rather than vague hopes “to learn more about U.S. medicine.” Consider goals in these domains:

Clinical knowledge

- “Understand diagnostic approaches to chest pain in the U.S.”

- “Learn how chronic diseases like diabetes are managed in outpatient settings.”

System and communication skills

- “Observe at least three family meetings or goals-of-care discussions.”

- “Learn how the team uses EHRs and order sets to standardize care.”

Career and application strategy

- “Clarify which subspecialty of internal medicine may fit me best.”

- “Obtain feedback on my CV and residency application strategy.”

Write your goals down and share 1–2 of them with your supervising physician during the first days. This signals intentionality and helps them tailor your experience.

Organizing Documentation and Compliance

Every institution has its own checklist, but most require:

Proof of immunizations and tests

- Hepatitis B, MMR, Varicella

- TB test (PPD or IGRA)

- Flu and/or COVID vaccination (seasonal and policy-dependent)

Background checks and training

- Criminal background screening

- Drug screening (less common, but possible)

- Online modules: HIPAA, infection control, safety training

Miscellaneous documents

- Copy of medical diploma or transcript

- Passport/visa documents if required

- Signed observership agreement or institutional forms

Start gathering these documents well in advance; delays in background checks or immunization records are common and can postpone your start date.

Clinical and Cultural Preparation

You will get more out of your observership if you refresh your medical knowledge and familiarize yourself with U.S. norms:

Clinical review

- Revisit common conditions in the specialty (e.g., hypertension, COPD, ACS, sepsis)

- Review recent U.S.-based guidelines (ACC/AHA, IDSA, ADA, etc.)

- Practice presenting cases concisely, even if you won’t be formally presenting

Cultural and communication preparation

- Learn typical structures: “SOAP” notes, SBAR communication, handoffs

- Watch videos of U.S. patient-physician interactions (YouTube, MedEd resources)

- Review basics of shared decision-making and informed consent in the U.S.

This preparation allows you to follow discussions more easily and ask higher-level questions.

How to Make a Lasting Impression During Your Observership

The way you conduct yourself day-to-day is what supervisors remember when later writing evaluations, providing advice, or deciding whom to recommend for opportunities.

Professionalism and Attitude

Show Up Prepared and On Time

- Arrive 10–15 minutes early each day

- Know the schedule: clinic days, rounds, conferences

- Bring a small notebook, pen, and any required ID badges

Reliability is one of the strongest positive signals you can send.

Maintain a Positive, Humble, and Curious Attitude

- Be enthusiastic without being intrusive

- Accept feedback graciously, even if it is critical

- Avoid complaining about long hours or comparing negatively with your home system

Supervisors are more likely to invest time in learners who are clearly motivated and respectful.

Dress and Professional Demeanor

Follow the institution’s dress code precisely:

Typical expectations

- Business-casual or professional attire

- White coat if required by the program

- Closed-toe shoes; minimal jewelry; clean, neat appearance

What to avoid

- Denim, athletic wear, overly tight or revealing clothing

- Strong perfumes or colognes

- Visible unprofessional logos or slogans

Your appearance is part of the first impression you make on patients, staff, and physicians.

Communication and Respect for the Team

Respect applies to everyone, not only faculty:

- Address all staff politely and by their preferred titles

- Learn and use people’s names whenever possible

- Acknowledge nurses, medical assistants, and administrative staff—they often are key to your daily experience and to whether you are welcomed back

When you show that you value each team member, the entire environment becomes more supportive of your learning.

Asking Thoughtful, Strategic Questions

You are there to learn, but clinical environments are busy. To ask good questions:

Choose your timing wisely

- During walking between patients

- After rounds

- During clinic downtimes or after the session

Frame questions to show preparation

- Instead of: “What is atrial fibrillation?”

- Try: “I read that U.S. guidelines for atrial fibrillation emphasize CHA₂DS₂-VASc scoring—how does that influence your anticoagulation decisions in older patients?”

Link questions to observed decisions

- “I noticed we ordered a CT rather than an MRI—can you share what factors guided that choice?”

This kind of questioning shows critical thinking and respect for the physician’s time.

Observing Actively and Taking Smart Notes

You are an observer, not a transcriber. Focus your notes on:

- Clinical reasoning patterns

- Language and phrases used in patient explanations

- How teams manage difficult conversations

- System processes: order sets, discharge planning, coordination with social work

Do not record identifiable patient information (names, dates of birth, medical record numbers). Keeping your notes de-identified is crucial for patient privacy and HIPAA compliance.

Patient Privacy and HIPAA Awareness

As an observer:

- Only enter rooms where you have been explicitly allowed and where patients have agreed to your presence

- Never photograph or record anything in patient-care areas

- Do not access EHRs unless specifically and formally permitted by the institution

- Avoid discussing cases in public spaces (elevators, cafeterias, hallways)

Demonstrating strong respect for confidentiality reassures staff that you are safe to have in clinical areas—and this reputation follows you.

Strategic Healthcare Networking During Your Observership

Networking should be organic and respectful, not forced. Some practical strategies:

Brief introductions

- “I’m Dr. [Name], an international medical graduate from [Country], here for a four-week observership in [Department]. I’m interested in [Specialty/Area].”

Ask for career advice

- “As an IMG, I’d value your thoughts on which experiences are most helpful for a strong residency application in this specialty.”

Attend educational events

- Morning report, noon conference, grand rounds, journal clubs

- Introduce yourself to presenters or residents afterward if appropriate

Follow up professionally

- Connect via email or LinkedIn after the observership

- Remind them briefly who you are and what you appreciated about working with them

Over time, these connections can lead to mentorship, research roles, or even residency interview recommendations.

Seeking and Using Feedback

Before your observership ends:

- Ask your supervising physician, “Could you share any feedback on my performance or how I can better prepare for residency?”

- Request specific feedback on communication style, clinical reasoning, and professionalism

- If appropriate and allowed by the institution, politely ask whether they might feel comfortable writing a letter of recommendation in the future, based on your observership

Be ready to accept both positive and constructive feedback. Then, document this feedback and incorporate it into your development plan.

After the Observership: Turning Experience Into Career Advancement

What you do after the observership often determines how much long-term value you gain.

Reflecting and Documenting Your Experience

Within a few days of finishing:

Write a structured reflection:

- Key clinical insights

- Memorable patient cases (de-identified)

- Communication or professionalism lessons

- Differences between your home system and the U.S. system

Capture details for your CV:

- Exact dates and duration

- Department and hospital name

- Supervising physician’s name and title

- Main activities and focus areas

This reflection will help you articulate your observership in personal statements and residency interviews.

Following Up with Gratitude and Professionalism

Send personalized thank-you messages to:

- Supervising attendings

- Residents or fellows who spent time teaching you

- Key administrative or nursing staff who helped coordinate your experience

In your messages:

- Express appreciation for their time and teaching

- Mention one or two specific things you learned

- Briefly share your next steps (e.g., “I will be applying in the 2026 Match for internal medicine.”)

Thoughtful follow-up leaves a lasting positive impression and keeps doors open.

Integrating Your Observership Into Your Residency Application

Use your observership experience across your residency materials:

Personal statement

- Highlight one or two impactful encounters or lessons

- Show how the experience clarified your specialty choice

- Demonstrate growth in understanding U.S. medical culture

ERAS application

- List under “Work Experience” or “Volunteer Experience” as “Observer”

- Provide a concise description: “Observed inpatient internal medicine team, attended rounds and conferences, participated in case discussions, and learned about chronic disease management in a U.S. academic medical center.”

Interviews

- Be prepared to answer:

- “What did you learn during your U.S. observership?”

- “How did it change your understanding of [specialty]?”

- “What differences did you notice between your home country’s healthcare system and the U.S.?”

- Be prepared to answer:

Your goal is to demonstrate that your observership was not passive, but a deliberate educational step in your medical career.

Maintaining and Growing Your Network

Healthcare networking does not end when you leave the hospital:

- Periodically send concise updates to mentors (e.g., after step exams, when you submit your ERAS application, or after Match results)

- Share significant achievements, such as publications or research projects

- Offer to contribute if opportunities arise (e.g., remote research collaboration)

Over time, you build a circle of professional contacts who can support and advise you across different phases of your career.

FAQs: Observerships for International Medical Graduates

Q1: How long does an observership typically last, and what duration is best for residency applications?

Most observerships last 2–8 weeks. A 4-week observership is common and usually enough time for faculty to get to know you. Programs value depth over sheer number of brief experiences; one or two well-executed 4-week observerships in your target specialty can be more impactful than multiple 1-week experiences.

Q2: Are there prerequisites for IMG observerships, and do I need to pass USMLE exams first?

Requirements vary by institution, but commonly include:

- Proof of medical education (diploma or enrollment verification)

- Immunization records and sometimes TB/flu/COVID documentation

- Background checks and institutional training modules

Some programs prefer or require that you have passed USMLE Step 1 and/or Step 2 CK, while others do not. Always check each program’s specific eligibility criteria.

Q3: Can observerships lead directly to residency interviews or positions?

Observerships do not guarantee interviews or residency positions, but they can:

- Increase your visibility to a program

- Provide U.S.-based mentors who can advocate for you

- Lead to letters of recommendation from U.S. faculty

- Help you tailor your application to that institution or region

Programs often value candidates who already know their system and have demonstrated professionalism in their environment.

Q4: How can I find observership opportunities as an IMG?

Common strategies include:

- Official hospital programs: Many academic centers have dedicated observership pages on their websites

- Networking: Ask faculty from your home institution, past supervisors, or alumni with U.S. connections

- Professional organizations: Specialty societies sometimes list observership or shadowing opportunities

- Direct outreach: E-mail department coordinators or faculty with a concise CV and a clear request

Start your search 6–12 months in advance, as spots can be limited and application processing can be slow.

Q5: Are observerships paid, and can I perform clinical tasks?

Observerships are almost always unpaid, and observers typically:

- Do not independently examine patients

- Do not write progress notes or orders

- Do not prescribe medications

Some institutions or roles may allow minimal supervised interactions (e.g., taking a brief history), but this varies and must always comply with hospital policy. Your primary role is observation and learning, not clinical service.

By preparing thoroughly, acting professionally, and reflecting intentionally, you can transform an observership from a simple requirement into a powerful stepping stone toward a successful residency match in the U.S. healthcare system.