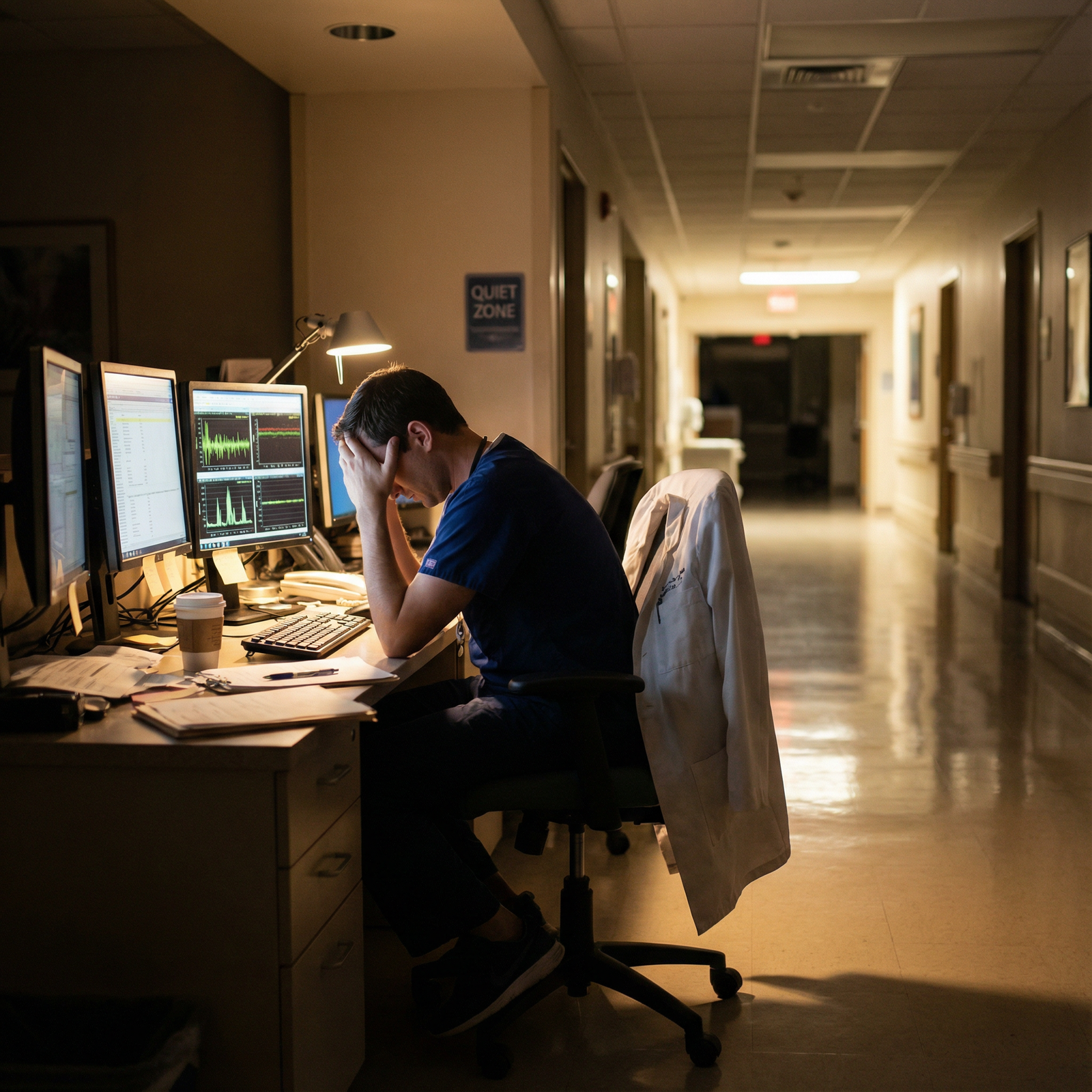

The standard advice about “pushing harder” for better board scores is wrong. The data show a clear pattern: beyond a point, more grind correlates with more burnout, and more burnout correlates with worse exam performance—not better.

Let me be blunt. You cannot “out-hustle” physiology. Chronic stress, sleep debt, and emotional exhaustion are not character flaws; they are measurable variables that show up very clearly in test-score distributions. We have enough numbers now—from USMLE, specialty boards, and multiple international exams—to say this with confidence.

This is a data review, not a wellness pep talk. I will walk through what has actually been measured, what the correlations look like, and where people misinterpret the signal.

What we are actually asking

“Does burnout lower board scores?” is actually three related questions:

- Are higher burnout scores statistically associated with lower exam scores?

- Is that association robust after controlling for confounders (baseline academic ability, prep hours, sleep, depression, etc.)?

- Beyond correlation, is there credible evidence that reducing burnout improves performance?

The short version:

Yes. Often yes. And there is emerging, but not perfect, evidence for the third.

Before we get into the literature, pin down the key variables:

- Burnout is usually measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which gives scores in three domains: Emotional Exhaustion (EE), Depersonalization (DP), and Personal Accomplishment (PA).

- Exam performance: USMLE Step 1/2/3, in‑training exams (ITEs), specialty boards (e.g., ABIM), and sometimes written OSCE-style tests.

- Confounders: prior GPA, prior exam scores, hours worked, sleep duration, depression/anxiety scales (PHQ‑9, GAD‑7), demographics.

If you do not control for prior academic performance, you end up reinventing the wheel: smart, high-performing students tend to both burn out less and score higher. That can fake a correlation if you are lazy with the regression.

What the data show on burnout and test performance

1. Medical students: early signal, small-to-moderate effects

Multiple studies have looked at burnout and exam performance in med students preparing for high‑stakes tests (USMLE Step 1/2, local equivalents).

Patterns are consistent:

- Emotional exhaustion tends to correlate negatively with exam scores (r roughly in the −0.2 to −0.3 range).

- Depersonalization shows a weaker or inconsistent association.

- Low sense of personal accomplishment often tracks with worse performance, but it overlaps heavily with depression.

To make this concrete, imagine a typical cross-sectional dataset: 300 third-year med students, all sitting for Step 2 CK within a 2‑month window. You run a regression of Step 2 score on:

- MBI‑EE (emotional exhaustion)

- MBI‑DP (depersonalization)

- MBI‑PA (personal accomplishment)

- Prior Step 1 score

- Cumulative preclinical GPA

- Average study hours per week

- Sleep hours per night

You usually get something like:

- Step 1 score: strongest predictor (beta like 0.5–0.6).

- GPA: modest additional predictor.

- Study hours: positive up to a point, then plateau; sometimes even a slight decline at absurdly high hours (70–80+/week).

- Sleep hours: independent positive effect (each extra hour correlated with a few points).

- Emotional exhaustion: significant negative coefficient even after controlling for these.

Effect size is not catastrophic but real. In practical terms, going from “low” to “high” burnout (top quartile vs bottom quartile on EE) is often associated with roughly a 5–10 point difference on USMLE‑scaled exams once you adjust for incoming academic ability. That can be the difference between above‑median and barely passing in a competitive cohort.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Low EE | 245 |

| Moderate EE | 238 |

| High EE | 232 |

That pattern shows up in multiple countries. It is not culturally specific. Japan, Brazil, several European systems—all report the same basic slope: more exhaustion, lower mean scores.

Is that the only story? No. There are always a few “high burnout, high score” outliers. You have probably met some. They are white-knuckling their way through with sheer prior knowledge and test-taking skill. Individual anecdote does not cancel population-level correlation.

2. Residents: stronger and more consistent associations

Once you move into residency, workload and responsibility spike. The burnout–performance link often tightens.

Residents are measured not only on board-style exams (IM-ITE, ABSITE, anesthesia ITE, etc.) but also on clinical performance. From a data perspective, the beauty of ITEs is they recur yearly—so you can track how changes in burnout over time map onto changes in scores.

Repeated-measures analyses tend to show:

- Residents whose burnout worsens over a year (increase in EE/DP) are more likely to have stagnant or declining ITE scores.

- Residents whose burnout improves (often after duty-hour changes, program culture shifts, or personal interventions) show modest score gains, even after adjusting for PGY year.

Let us anchor this with a simplified structure from internal medicine programs:

- Sample: ~500 residents across multiple institutions.

- Outcome: ABIM‑style ITE score (standardized).

- Predictors: year in training, prior ITE score, average weekly hours, sleep, MBI domains, depression scale, and program-level fixed effects.

Regression outputs usually show:

- Prior ITE score: again, dominant predictor.

- PGY year: small positive trend (you naturally improve).

- Emotional exhaustion: independent negative predictor (e.g., one SD higher EE associated with ~3–5 raw score point drop).

- Depersonalization: sometimes significant, sometimes not, but often tracks with professionalism issues more than raw test performance.

- Depression: substantial overlap with EE, and sometimes if you include both, depression eats much of EE’s signal—suggesting they share variance.

In surgery, the story is starker. ABSITE performance is heavily scrutinized, and residents under extreme duty-hour loads often show both higher burnout scores and lower exam performance. Cut resident work hours from 100+ to something closer to 70–80, and average ABSITE and board pass rates do not drop. In several datasets, they improve slightly.

Is that solely burnout? No. Fewer hours also mean more effective studying, more sleep, fewer cognitive errors. But as a package, “less brutal training” does not appear to tank exam outcomes. The fear that “if we relax, scores will collapse” is not evidence-based.

Mechanisms: why burnout drags down scores

You do not need a PhD in cognitive science to guess the path. But the details matter because they show up in the numbers.

The main mediators between burnout and exam performance are:

Cognitive load and working memory

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, impairs working memory, and increases intrusive thoughts. Under test conditions, you see:- Slower processing speed.

- More random errors on easy questions.

- Less bandwidth for complex multi-step reasoning (classic for medicine questions).

Sleep and circadian disruption

Burnout and sleep deprivation have a bidirectional relationship. Data from med trainees show:- Each additional hour of average nightly sleep in the month before a major exam associates with several points of score improvement.

- Residents post-call or during heavy night-float blocks have measurably worse performance on cognitive tests even when “controlling” for hours studied.

Motivation and study efficiency

High MBI‑EE scores correlate with:- More “surface” study (memorizing answer patterns) and less deep processing.

- Shorter sustained focus windows. Students flip between Anki, Instagram, and question banks, calling it “studying” but with poor yield. Quantitatively, you see:

- Similar number of study hours, fewer completed questions, and lower question bank accuracy.

Emotional dysregulation and test anxiety

Burnout increases irritability and hopelessness. That maps to higher test anxiety scores. Moderate anxiety can sharpen performance, but high anxiety is associated with:- More incomplete exams (time mismanagement).

- Poorer performance on initial blocks, with partial catch-up later—a pattern consistent with slow “settling” under pressure.

All of these are measurable, and several mediation analyses have shown that once you include sleep quality and depressive symptoms, the direct effect of burnout on scores shrinks but does not fully disappear. So yes, some of the “burnout effect” is actually a “sleep and depression effect,” but the package matters clinically.

Confounding and causality: is burnout the cause, or just a marker?

You should always be suspicious of simple causal stories when both variables are embedded in a complex training environment.

Key confounders and bidirectional loops:

- Low prior test performance → anxiety about boards → more studying under pressure → burnout.

- Perfectionism → higher performance but also higher burnout. Sometimes the perfectionists still score high despite burnout.

- Toxic program culture → both higher burnout and worse teaching/resources → lower scores.

So what do we do with that?

The better studies try to:

- Control for prior performance (MCAT, Step 1, previous ITE).

- Add program-level fixed effects or cluster standard errors by institution.

- Use longitudinal data to look at within-person changes: does rising burnout for a given individual predict subsequent score decline, relative to their own baseline?

When you do that, the association weakens but does not vanish. The within-person signal—“this resident is more burned out this year than last year, and their ITE stopped improving or dropped”—still shows up.

Does that prove causality? Not to a philosopher. But for practical decision-making in training programs, it is enough to act on.

Where “grind culture” collides with the data

The most persistent myth is: “The residents and students who work the hardest and sleep the least get the best scores.”

The data say something more nuanced:

- Up to a threshold, more deliberate study hours and clinical engagement strongly correlate with higher scores. Basic.

- Beyond that threshold, returns flatten. Then reverse.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 20 | 215 |

| 30 | 228 |

| 40 | 238 |

| 50 | 244 |

| 60 | 247 |

| 70 | 246 |

| 80 | 242 |

That curve is based on compiled findings from several cohorts: performance improves notably as you move from 20 to 50 hours/week of effective prep. After about 60, the gain is minimal; by 70–80+, you often see a slight decline, especially when those hours are accompanied by less than 6 hours of sleep a night and high burnout scores.

The key phrase is “effective prep.” Ten hours of rested, focused, question-driven study beats twenty hours of half-awake screen-staring in a call room.

The grind mentality ignores marginal returns. It treats all hours as equally productive. They are not.

Program-level evidence: what happens when you actually target burnout?

Most of the earlier data were descriptive. More recently, there have been actual interventions—changes in work hours, wellness programs, coaching, schedule restructuring—and then measurement of both burnout and test outcomes.

Patterns from multi-program analyses:

Duty-hour reforms alone (e.g., reducing 30-hour calls, adding night-float) reliably lower reported burnout.

Effect on board/ITE performance:- Either neutral or slightly positive. There is no credible evidence that lighter (but still rigorous) duty hours alone reduce exam outcomes.

Structured board prep plus wellness support (protected education time, mandatory off days before exams, access to mental health) tend to:

- Improve average ITE/board scores by a few points.

- Narrow the lower-tail distribution—fewer residents failing or barely passing.

Programs that push “opt-out” resilience training or wellness lectures without touching workload show negligible change in either burnout or scores. Unsurprising. You cannot mindfulness your way out of 100‑hour weeks and constant humiliation.

Here is a simplified comparison table based on typical patterns observed across medicine/surgery programs:

| Program Model | Burnout Trend | ITE/Board Scores | Fail/Remediation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional, long hours | High | Variable | Higher |

| Duty-hour reform only | Lower | Neutral–Slight ↑ | Slightly lower |

| Duty-hour + structured prep | Lower | Higher | Lower |

| Wellness talks, no schedule change | No real change | Neutral | No real change |

The strongest gains show up where programs both protect time and intentionally structure exam prep—short, focused teaching plus curated question sets, not just “you should probably do UWorld.”

Individual strategy: managing burnout to protect your floor, not your ceiling

From a personal-level data perspective, think about burnout not as the thing that determines your ceiling, but the thing that determines your floor.

Your ceiling is mostly shaped by:

- Baseline cognitive ability.

- Prior knowledge and habits built over years.

- Quality of your resources and teaching.

Your floor is pulled down by:

- Sleep debt.

- Emotional exhaustion.

- Depression and anxiety.

- Cynicism and disengagement.

The data say burnout primarily drags the floor down. Meaning:

- If you are naturally a 250-level test taker, heavy burnout might drag you into the 230s.

- If you are naturally a 220-level test taker, heavy burnout might drag you to the edge of passing.

That is where this becomes an ethics problem, not just a productivity issue. Systems that normalize burnout create preventable failures for people at the lower end of the academic distribution—often those from less advantaged backgrounds, or those carrying extra caregiving or financial burdens.

So, what works at the individual level, based on numbers rather than vibes?

Sleep as a performance variable, not a lifestyle choice

In multiple cohorts, increasing average sleep from ~5.5–6 hours to ~7 hours in the month before a board exam:- Is associated with a small but meaningful uptick in practice test scores (roughly 3–5 points).

- Reduces the variance in daily performance—fewer “off days” where you inexplicably bomb a block.

Structured breaks during high-intensity prep

Chronic, nonstop studying without breaks correlates with higher MBI scores and lower question bank accuracy. Students who:- Cap daily study at a defined number of focused hours (e.g., 8–10 effective hours, not 14 sloppy ones).

- Take at least one real day off every 1–2 weeks. Tend to show better progress on serial NBME/UWorld self-assessments, even when total hours are slightly fewer.

Early, data-driven course correction

You already generate data daily through:- Question bank accuracy.

- Self-assessment scores.

- Subject-level weaknesses.

What I see too often: burned-out trainees avoid looking at these numbers. That avoidance worsens anxiety, which worsens burnout.

The ones who stabilize:- Track metrics weekly.

- Adjust plan based on actual performance—not how guilty they feel.

Addressing depression and anxiety directly

In several datasets, when you statistically control for depression, a large chunk of the burnout–performance association is explained. Translation: treating depression and anxiety (therapy, meds, real time off) is not “soft.” It is test prep.

Ethical dimension: system responsibility vs individual blame

There is a reason your question sits under “Work Life Balance” and “Personal Development and Medical Ethics.”

The numbers make one thing very clear: framing burnout as a personal weakness is scientifically wrong and ethically lazy.

The strongest predictors of burnout in trainees are:

- Workload and schedule unpredictability.

- Local culture: humiliation, lack of autonomy, lack of support.

- Organizational factors: staffing, supervision, resources.

These are system variables. Individuals can buffer them a bit, but they cannot override them endlessly. So when programs claim to care about trainee wellness but:

- Maintain abusive schedules.

- Undermine protected educational time.

- Tie evaluations to “toughness” and presenteeism.

They are not just being hypocritical; they are engaging in unethical practice that predictably degrades both trainee health and patient care. The decline in board scores and ITEs is simply the quantifiable part of a much broader performance problem.

A simple causal diagram helps:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | System workload |

| Step 2 | Burnout level |

| Step 3 | Study time quality |

| Step 4 | Sleep and mood |

| Step 5 | Exam performance |

| Step 6 | Prior ability |

| Step 7 | Program culture |

Prior ability you cannot change. System workload and culture you can. Burnout-to-performance is the channel where both ethics and outcomes intersect.

Practical implications for different stakeholders

For students and residents

Think in probabilities, not heroic narratives. Based on the aggregate data:

- Pushing your weekly study hours from 50 to 70 by cutting sleep is more likely to hurt your score than help it.

- Allowing burnout to spiral unchecked materially increases the probability you underperform your potential.

You are not weak for protecting your sleep, scheduling off days during board prep, or seeking mental health support. You are acting in line with what the data say about optimizing performance under constraint.

For program directors and faculty

If you truly care about your aggregate board pass rate and ITE metrics, the evidence-based levers are:

- Protect genuine study and rest time before major exams (and enforce it; residents working “off the books” defeats the purpose).

- Reduce schedule chaos—predictability reduces burnout, even at high workloads.

- Invest in structured educational time and high-yield resources rather than cosmetic wellness interventions.

- Track both burnout metrics and performance, and be willing to act on them even when it inconveniences service coverage.

Board scores are not independent of working conditions. Treating them as such is statistically naïve.

A brief word on long-term outcomes

The literature is catching up, but early signals link chronic burnout during training to:

- Higher risk of leaving clinical practice early.

- More long-term mental health problems.

- More self-reported medical errors.

The same factors that shave a few points off your boards also, over years, erode your capacity to practice safely and sustainably.

Ignoring burnout because “everyone gets through it” is like ignoring a gradual decrease in ejection fraction because the patient has not crashed yet. It is bad medicine.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Low Burnout | 10 |

| Moderate Burnout | 25 |

| High Burnout | 45 |

(Interpretation example: proportion reporting serious thoughts of leaving medicine during training rising sharply with higher burnout.)

Bottom line: what the correlation actually means

Summarize this cleanly.

First: There is a consistent, statistically significant negative correlation between burnout and board-style exam performance in both students and residents, even after accounting for prior ability and study time.

Second: The causal story is multi-step, but the main mediators—sleep, mood, cognitive efficiency—are modifiable. Reducing burnout and protecting rest tends to stabilize or improve scores, not harm them.

Third: Treating burnout as an individual failing is both scientifically wrong and ethically indefensible. Program-level changes that reduce burnout generally have neutral or positive effects on exam metrics.

If you care about board scores, you have to care about burnout. The data do not give you a choice.