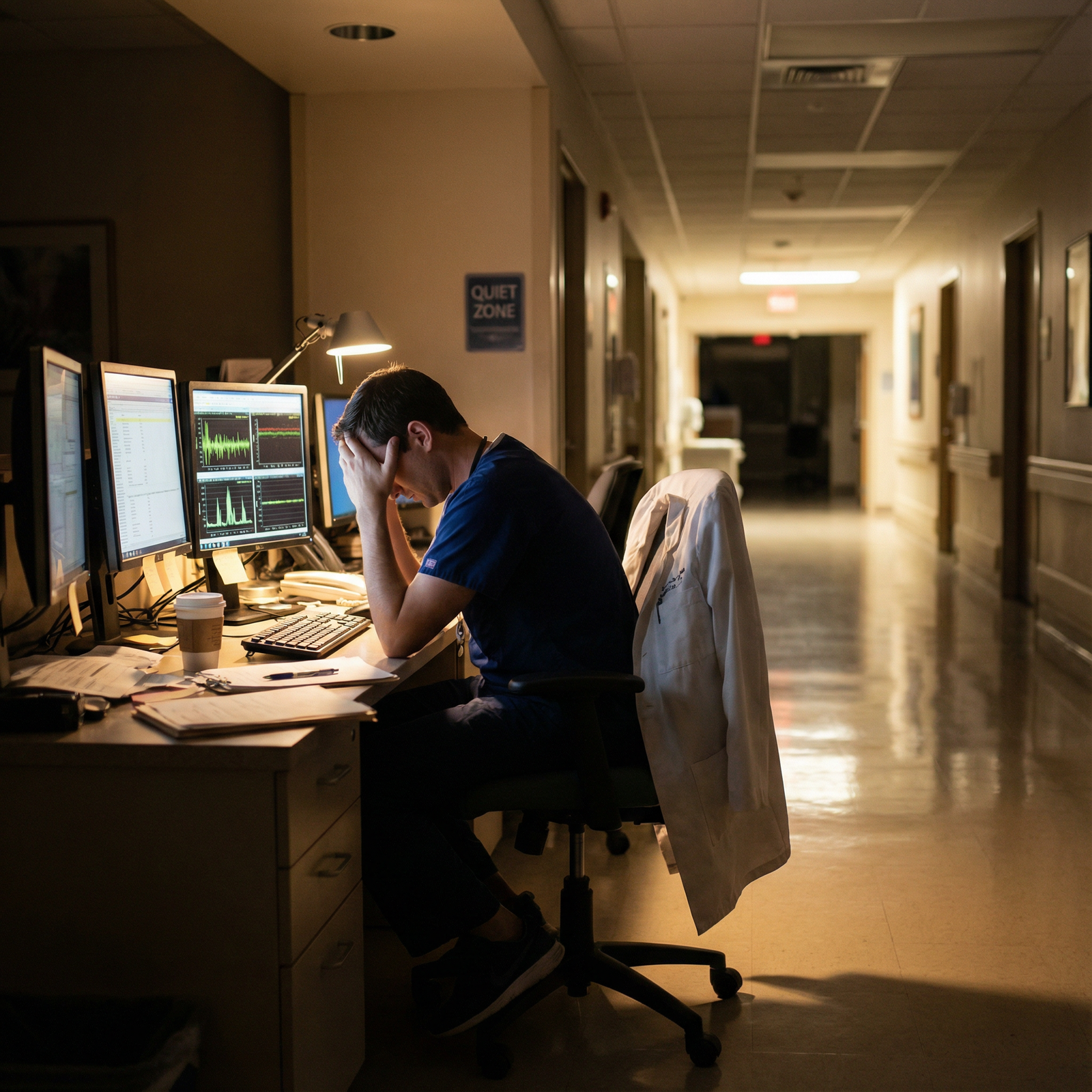

What do you do when your pager, your parent’s medication schedule, and your own collapsing mental health are all screaming at you… at the same time?

If you’re in med school or residency and also caring for a sick parent, you’re in one of the hardest double-binds in medicine. People will say “that must be so hard” then immediately ask if you can stay late to cover. Your classmates will worry about shelf scores; you’re worrying about whether your mother will fall in the shower.

Let’s treat this like what it is: a high-acuity, long-term situation. Not a “be more resilient” poster. You need tactics.

Step 1: Get Real About the Situation You’re Actually In

Most trainees in this spot underestimate the severity of their own situation. Because that’s what you’ve been trained to do—minimize your needs, keep going.

Here’s the blunt reality: you’re doing two demanding jobs at once.

- Trainee physician (med student, resident, fellow).

- Primary or near-primary caregiver for a sick parent.

That has consequences.

Start by naming exactly what you’re dealing with. Not “my dad’s not doing great.” I mean specifics:

- Diagnosis: CHF with frequent exacerbations? Dementia? Metastatic cancer on chemo?

- Functional level: Can they toilet alone? Eat independently? Walk unassisted?

- Time demands: How many hours a week are you spending on:

- Direct care (bathing, meds, appointments)

- Logistics (insurance calls, forms, pharmacy)

- Emotional labor (sitting with them when they’re afraid or confused)

Write it down. On one page. No prose. Just brutal bullet points.

Why? Because this becomes your script for conversations with program leadership, school administration, and siblings who think “you can handle it” because you’re in medicine.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical Work | 60 |

| Studying | 10 |

| Parent Care | 25 |

| Everything Else | 5 |

If your combined weekly load is consistently >80–90 hours, you are not just “busy.” You are in a chronic overload state. That informs how aggressive you need to be about boundaries and accommodations.

Step 2: Decide Your Non‑Negotiables (Before Crisis Hits)

If you wait until a 3 a.m. call that your mother fell to decide what you’re willing to miss, you will make panicked, guilt-driven decisions. Build your “if X then Y” rules now.

Think in three buckets:

- Absolute emergencies where you drop everything

- Parent in the ED with stroke symptoms

- Rapid deterioration, ICU transfer

- New severe confusion and they live alone

For these, your rule might be: “I will leave any clinical setting and call my chief/faculty on the way out. I will accept the professional fallout.”

- Important but not emergent

- New oncology visit

- Family meeting about goals of care

- Pre- or post-op consultations

Here, you plan: request time off or half-days weeks in advance, get coverage, communicate clearly. Treat it like your own essential procedure.

- Things you will not always be present for

- Every routine follow-up

- Every scan result discussion that isn’t time-sensitive

- Every home health visit

This is harsh. But necessary. You cannot physically attend everything if you’re on q4 call or in ICU month. Decide now which ones you’ll miss and how you’ll ensure someone else is there (another family member, trusted friend, or even you on speakerphone post-call).

Write your three buckets in your notes app. When something comes up, put it in a bucket, then act accordingly. It reduces the emotional chaos.

Step 3: Stop Being the Only Adult in the Room

You might be the only medically literate person in the family. That does not mean you should be the only responsible one.

You need a care team. Not in the abstract “it takes a village” way. Literally list names.

| Role | Possible Person/Resource |

|---|---|

| Medical lead | You + primary care physician |

| Backup decision maker | Sibling, aunt/uncle, close friend |

| Logistics lead | Sibling, spouse, cousin |

| Daytime eyes-on | Home health aide, neighbor |

| On-call local help | Neighbor, nearby relative |

Then you make actual asks. Not the vague “let me know if you can help.” That gets you nothing. Try:

- “Can you come Tuesdays 5–8 pm so I can study/sleep?”

- “Can you be the default person to go to appointments I cannot attend?”

- “Can you handle all insurance phone calls and send me a brief summary?”

If you have no family nearby or they’re genuinely unavailable or useless (it happens), you pivot to formal supports.

Look at:

- Home health agencies (even a few hours/week helps)

- Adult day programs

- Social work consult through your parent’s primary or hospital system

- Community resources: local senior centers, religious communities, disease-specific orgs (Alzheimer’s Association, American Cancer Society)

If money is tight, say that to the social worker. They cannot read your mind, but they usually know low-cost or subsidized options. I’ve seen trainees discover benefits their parents were eligible for years ago but never accessed because nobody asked the right person.

Step 4: Be Strategic About What You Tell Your Program/School

Here’s the part people screw up. They either:

- Tell no one and crash spectacularly, or

- Trauma-dump to the wrong person at the wrong time and get labeled “unreliable.”

You’re aiming for a middle path: targeted transparency.

Who actually needs to know?

- Med students: Dean of students / student affairs, course/clerkship directors when relevant

- Residents/Fellows: Program director, chief residents, maybe one trusted faculty mentor

What do you say? You use the one-page situation summary from Step 1 and translate it into “program language”:

Brief situation:

“My mother has metastatic breast cancer and significant functional decline. I am one of her primary caregivers and the only medical person in the family.”Concrete impact:

“This primarily affects my evenings/nights and occasional weekdays for major appointments and emergencies.”Specific requests:

- For med students:

“I may need 1–2 excused absences for major oncology appointments, with advance notice. If an acute emergency happens, I will inform the clerkship director as soon as possible and make up missed shifts.” - For residents:

“I am asking for flexibility with scheduling: avoiding back-to-back ICU months for the next year, and the ability to step out for true emergencies occasionally, with coverage arranged by chiefs when possible.”

- For med students:

Your commitment:

“I am committed to completing all required duties and communicating proactively. I am not asking for reduced expectations, just structured flexibility given the caregiving situation.”

Then you send an email requesting a meeting, not dumping this in a hallway conversation between pages.

Step 5: Use Formal Accommodations and Leave Without Apologizing It Away

There is this toxic myth in medicine that if you ask for any accommodation, you’ve failed some unspoken toughness test. Ignore that. The toughness test is surviving this without imploding.

Things you may be entitled to or can reasonably request:

- Short-term leave of absence

- Part-time status (for some fellowship/graduate programs)

- Schedule modifications (cluster heavy rotations away from crises)

- Extra time to complete certain requirements

- Remote completion of some didactics or admin requirements

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Schedule flexibility | 70 |

| Short leave | 40 |

| Reduced duties | 25 |

| Remote coursework | 35 |

You’re not gaming the system. You’re trying not to break.

If you’re in residency and your parent’s health suddenly tanks, a 4–6 week personal leave is not insane. Programs survive maternity leaves, medical leaves, military leaves. They can survive yours. They may need to extend your training. That is still better than you white-knuckling through and making errors or ending up in the hospital yourself.

Key point: do not wait until you’re non-functional. If you’re crying in stairwells every day and dreading both home and work, that’s your early warning sign—not “rock bottom.”

Step 6: Triage Your Guilt (Because It Will Eat You Alive)

This situation runs on guilt. Guilt that you’re not studying enough. Guilt that you’re not home enough. Guilt that you’re not grateful enough. It’s endless.

You will not get rid of guilt. You can make it smaller and less decisive.

Here’s the mental reframe I’ve seen help:

You are not choosing between “being a good child” and “being a good doctor.” You are choosing between:

- Being a burned-out, resentful caregiver who might make dangerous mistakes at work

versus - Being a sustainable caregiver-doctor hybrid who sometimes misses things but is present and functional when it counts.

That second one is the ethical choice. For your patients and your parent.

Also: your parent’s illness is not an exam you can ace. There is no perfect set of actions that will make you feel like “I did everything.” That fantasy needs to die early or it will torture you.

Concrete tactic: When guilt hits, ask yourself one question:

“Given the constraints I have, am I acting with basic decency and effort?”

Not perfection. Not martyrdom. Basic decency and effort.

If the honest answer is yes, then guilt is just noise. Note it, but do not obey it.

Step 7: Don’t Be Your Parent’s Only Doctor

You’ve been in lecture for two months and suddenly your family is looking at you like you’re the attending oncologist.

You are not your parent’s physician. And you should not pretend to be.

You can:

- Help translate medical jargon

- Advocate for appropriate workup and referrals

- Catch obviously missed safety issues (e.g., major drug interactions, fall risks)

You should not:

- Be the only one deciding major treatment pivots

- Prescribe or write orders for them if there’s any boundary issue (and there is)

- Override the actual treating team because “I’m in medicine”

Instead, find one clinician in their system who will be the real point person: PCP, oncologist, geriatrician, whoever fits. Ask for a dedicated visit or phone call where you introduce yourself as “family and a medical trainee” and build a working relationship.

You can say:

“I’m in medical training, so I understand a lot, but I am also very emotionally involved and I do not want to be the only person steering this ship. Can we set up a clear plan and communication channel so we’re not scrambling at 2 am?”

You’re allowed to be both informed and vulnerable. Those two are not mutually exclusive.

Step 8: Create Micro-Systems So You’re Not Running On Memory

Your brain is already over-utilized. Stop trying to remember everything. Externalize.

Systems that actually work in this situation:

Command center binder or shared drive

- Medication list (updated, doses, who prescribed what)

- Problem list and summary

- Appointment list with locations, phone numbers

- Legal docs: advance directives, healthcare proxy, power of attorney

Shared calendar (Google, Apple, whatever)

- Put all appointments there

- Color code: red = must-attend, yellow = nice-to-attend, grey = others can handle

Communication rules with family

- Group chat for updates (not 500 side-texts)

- Only true emergencies = phone calls at night

- One person designated to talk to clinicians most of the time

- Template messages

- Draft text/email you can reuse with chiefs:

“Family medical emergency with my parent. I need to step away now; I will update you within X hours and coordinate coverage.”

- Draft text/email you can reuse with chiefs:

When you’re post-call, sleep-deprived, and your sibling texts “what’s the med dose again???” you’ll be glad you built this.

Step 9: Protect a Tiny, Non-Negotiable Slice of Your Own Life

You probably rolled your eyes at that header. Fair. But hear me out.

You cannot make this sustainable if literally every waking moment is either clinical work or caregiving. That is how people end up drinking, dissociating, or just numb.

I’m not talking about yoga retreats. I mean one small, protected thing that’s for you and not for anyone else.

Examples I’ve seen work:

- 20-minute walk alone before you go into the house after a shift

- A weekly hour in a coffee shop with headphones and a book that is not about medicine

- Two therapy sessions a month, booked like they’re tumor board—immovable

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 hours | 30 |

| 1-2 hours | 35 |

| 3-4 hours | 25 |

| 5+ hours | 10 |

If someone pushes back—program, family, or your own guilty brain—remember: you are not abandoning your parent to go party. You’re preserving the one person who is holding multiple worlds together. That person needs oxygen.

Step 10: Think Ahead About Ethical and Emotional Landmines

There are some specific heavy spots you’re likely to hit. Better to anticipate them than be shocked.

Aggressive care vs comfort care

- You’ll feel a pull to “do everything” because you’re in medicine.

- Your parent may or may not want that.

- Work now on clear conversations about what they actually want if things go badly. Document it.

Family disagreements

- The “you’re the doctor, you decide” trap.

- Or the opposite: relatives who accuse you of “giving up too early” because you opposed the 4th ICU admission.

- Decide early: you are one voice, not the sole moral authority. Line up the treating team, ethics consults if needed. Spread the moral weight.

Boundary with your own patients

- Treating critically ill patients similar in age or diagnosis to your parent will hit differently.

- It’s ok to tell a supervisor, “I’m not the best person to lead this family meeting; my parent is going through something very similar and I’m not neutral.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Parent health worsens |

| Step 2 | Go to ED |

| Step 3 | Call primary or specialist |

| Step 4 | Goals of care talk |

| Step 5 | Adjust treatment |

| Step 6 | Outpatient visit |

| Step 7 | Family meeting |

| Step 8 | Acute emergency? |

| Step 9 | ICU level? |

| Step 10 | Aggressive vs comfort |

You can do right by your parent and still have moments you question for years. That’s normal. Talk to someone outside the family—a therapist, faculty mentor, chaplain. The point is not to erase the doubt, but to not carry it alone.

Step 11: If You’re Far From Home

Plenty of trainees are in another state—or another country—while a parent gets sick at home. Then you get the worst combination: helplessness, pressure to fly back constantly, and guilt for not being physically there.

Here’s what “showing up” can look like from a distance:

- Be the medical interpreter on speakerphone during key visits

- Take over all behind-the-scenes admin: portals, insurance, med refills, organizing records

- Schedule regular check-ins with your parent that are not only about illness

- Plan purposeful visits for big milestones: major surgeries, new diagnoses, palliative care transitions

And sometimes, you have to make a brutal call: move closer, delay training, or accept being the distant-but-involved child. All three are morally defensible. The only indefensible choice is pretending you have no choice and then drowning silently.

Step 12: When It’s Over (Because Eventually, It Will Be)

Whether your parent stabilizes or dies, this period will end. You’ll be left with:

- A weird combination of relief, grief, and emptiness

- A training record that maybe has some leaves, extensions, or odd schedule gaps

- A very different sense of what matters in medicine

Do not rush to “get back to normal.” There is no old normal anymore.

Professional moves:

- If your CV now has a gap or extended training, you can summarize it simply:

“Took a personal leave during residency to provide care for a seriously ill parent.”

Most decent programs and employers understand that. - Use what you learned in personal statements or interviews—but carefully. Not a trauma monologue. More: “This experience changed how I approach patients and families like this.”

Personal moves:

- Actually process it. The temptation is to sprint straight into the next achievement. You’ve been in survival mode. You need a decompression phase.

- Take the empathy and boundary lessons forward. Do not forget them once life is easier.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. Should I take a leave of absence or just “push through”?

If you’re asking this earnestly, you’re probably closer to needing a leave than you admit. Look at your functioning: Are you making more mistakes? Snapping at patients or family? Crying most days? That’s not normal training stress. A 4–12 week leave can prevent a total crash. Speak with student affairs or your program director and get concrete about options instead of making this a moral question. It’s not a moral failing to pause.

2. How much do I have to tell my program or school about my parent’s condition?

You do not owe anyone every clinical detail. You owe them enough context to justify the accommodations you’re asking for and to show you’re thinking clearly. “My father has advanced heart failure and I’m a primary caregiver, which requires frequent appointments and occasional emergencies” is enough. You can keep prognosis, specific treatments, and family dynamics private unless there’s a direct safety implication.

3. What if my siblings are not helping and expect me to handle everything because I’m the doctor?

You stop accepting that premise. Being the medically trained one does not equal being the 24/7 caregiver, errand runner, and emotional sponge. Spell out what you can and cannot do given your schedule. Offer specific tasks they can own completely. If they refuse, then you make decisions assuming you have minimal family support and lean harder on formal resources. You cannot fix sibling dysfunction while on night float. Accept the limits and protect your bandwidth.

4. How do I handle feeling like a “bad doctor” when I prioritize my parent, or a “bad child” when I prioritize training?

You’re stuck in a rigged game where any choice can be framed as failure. The way out is to stop grading yourself by imaginary perfection standards. Ask instead: “Did I act with reasonable care for both my patients and my parent, given finite time and energy?” Some days your parent will come first. Some days a crashing patient will. Over weeks and months, you’re aiming for overall decency, not daily perfection. A therapist can help you untangle this if it’s paralyzing you.

5. What’s one thing I can do this week to make this situation less overwhelming?

Build a 1-page snapshot of your parent’s situation and your caregiving load, then schedule one concrete conversation using it. That might be with a social worker, your program director, or a sibling. Do not wait for the “perfect time.” Get it on the calendar. That single move—turning a private burden into a shared, structured problem—usually lowers the temperature more than any self-care quote.

Open your calendar right now and block 30 minutes in the next 3 days to write your one-page situation summary and send one email—to family, your program, or a social worker—to start building your support system.