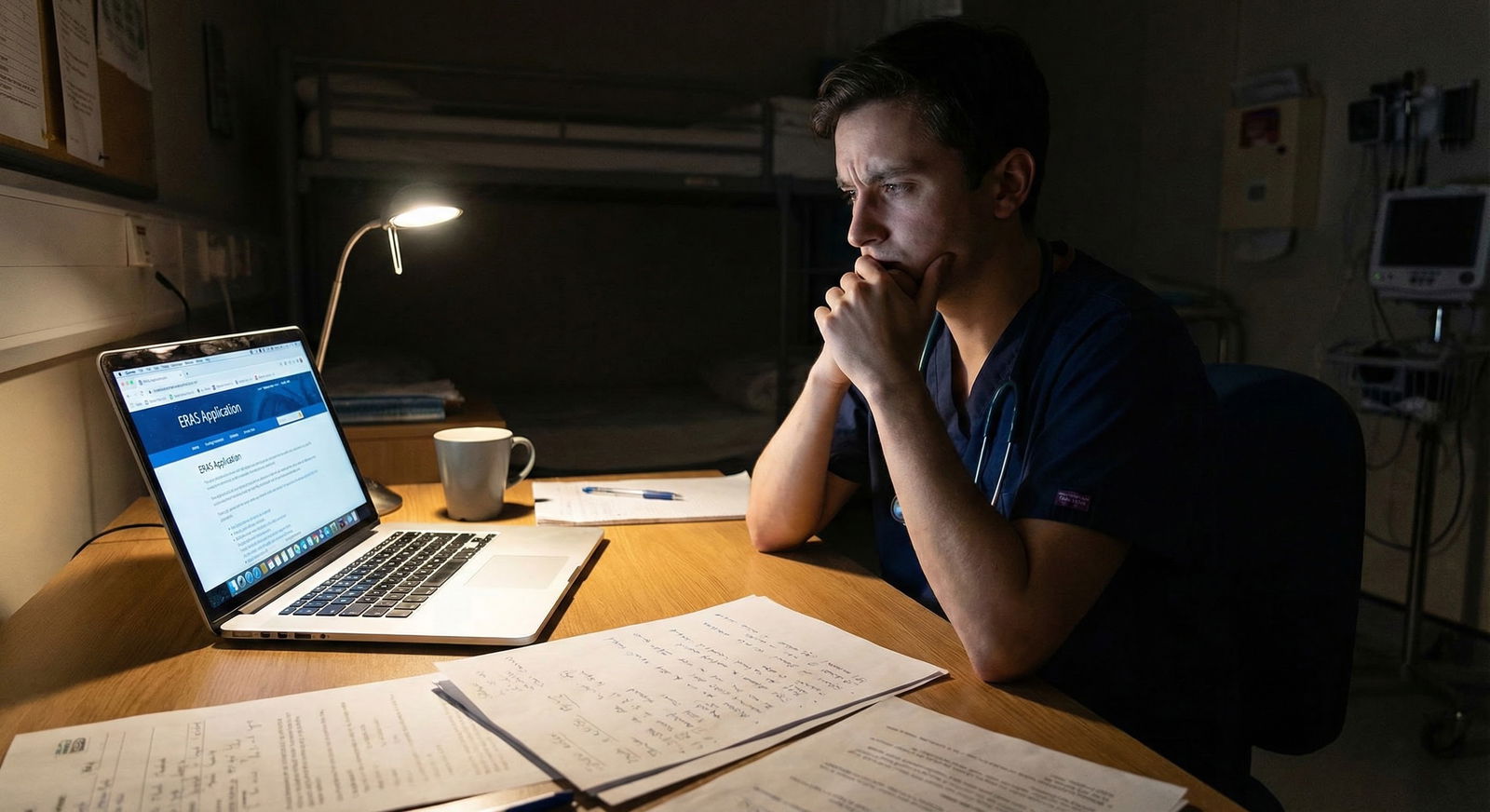

It is late July. Your Sub‑I just ended. Everyone told you this was your chance to “show you can function as an intern.” Instead, you are walking out with:

- An “above expectations” instead of “honors” (or worse, just “meets”).

- Vague feedback like “needs to be more proactive.”

- A senior who said, “You’re nice, but I just did not see you lead the team.”

And ERAS opens in a few weeks.

You are replaying missed opportunities: the sign‑out you fumbled, the note that came back “rewrite this,” the consultant who seemed annoyed you called. You are wondering if you just tanked your shot at your chosen specialty.

Let me be blunt: a mediocre Sub‑I is not ideal, but it is very fixable if you move fast and with a plan. Not vibes. A plan.

Here is how to repair the damage, extract value from a weak rotation, and walk into ERAS with a story that makes sense rather than screams, “I peaked on Step 2 and coasted.”

Step 1: Get Out of Denial and Get Precise About What Went Wrong

Vague guilt does not help you. Specific patterns do.

You need a post‑mortem on that Sub‑I. Not a pity party. A clinical case review on yourself.

1.1. Break down the rotation into domains

Pull out your evaluation if you have it. If you do not, use your memory and any mid‑rotation feedback you got. Break performance into:

- Clinical reasoning / medical knowledge

- Patient ownership & reliability

- Communication with team (notes, presentations, pages)

- Communication with patients / families

- Professionalism / work ethic

- Team role (initiative, “acting intern” behavior)

Now ask, bluntly, for each domain: Was I at intern level, almost there, or clearly below? Be honest. No one else will see this.

1.2. Translate garbage feedback into actionable problems

Common vague comments and what they usually mean:

“Be more proactive”

→ You waited to be told what to do, did not pre‑chart, did not call consults without being instructed, did not anticipate next steps.“Work on efficiency”

→ Notes late, never first with the plan, disorganized prerounds, slow to put in orders, too long on presentations.“Could read more”

→ You did not consistently know the “next step” in standard problems for that specialty. You probably asked basic questions that a Sub‑I should know cold.“Needs more confidence”

→ You hedged on every plan, never volunteered to call family, did not speak up on rounds, looked unsure even when you were correct.“Quiet on the team”

→ No one remembers you taking ownership of anything. You might have been pleasant but invisible.

Write down the exact phrases you heard and map them to concrete behaviors. If you are not sure, ask.

1.3. Ask for one brutally honest debrief

You need one real conversation, not seven watered‑down ones.

Pick:

- The senior resident who worked with you the most or

- The attending who seemed invested and not rushed

Script it. Send a short, direct email:

“Thank you again for the opportunity to work with you on Sub‑I. I want to improve before residency applications go in. Could we do a quick 10–15 minute debrief sometime this week? I am specifically trying to understand what was holding me back from an intern‑level performance and what I can realistically improve over the next 4–8 weeks.”

During the conversation, ask three questions:

- “If you had to summarize my biggest limitation on this rotation in one sentence, what would it be?”

- “Can you give me 2–3 specific examples where I came up short compared with your strongest Sub‑Is?”

- “If I had another 4 weeks with you, what concrete things would you want me to do differently every single day?”

Do not defend. Do not explain. Just: “Thank you. That helps. I am going to work on that.”

Capture phrases. You are going to turn those into a training plan.

Step 2: Decide If This Sub‑I Will Be Part of Your Application Narrative

You have to make a choice: lean into this Sub‑I as part of your story, or minimize its visibility and build your case elsewhere.

2.1. Look at your whole clinical record

Step back:

- How were your core clerkship grades in this specialty and others?

- Any other Sub‑Is (upcoming or completed)?

- Any away rotations planned?

- How strong are your letters outside this rotation?

The Sub‑I only sinks you if:

- It is your only exposure in that specialty, and

- It is clearly weaker than everything else.

If you have other strong rotations in that field, this becomes a data point you can contextualize, not a death sentence.

2.2. Decide what you need from this Sub‑I

There are three main “outputs” from a Sub‑I:

- Grade (honors / high pass / pass)

- Letter of recommendation

- Reputation within that department (the hidden currency)

Given your performance, choose your priority:

- If the grade is mediocre but the attending likes your trajectory → you might still get a solid letter emphasizing growth.

- If you sensed they were lukewarm and distracted → this may not be the letter you want anchoring your ERAS.

- But the reputation can still matter for your home program’s rank list later, especially in smaller specialties.

If you decide this rotation will not be your flagship letter, fine. That just means the next step is: build a stronger counter‑narrative fast.

Step 3: Build a Repair Rotation (or Two) Before ERAS Locks In

You do not fix a weak Sub‑I by “reflecting more.” You fix it by doing another rotation where you act like an intern from day 1 and get it documented.

3.1. Identify your next best platform

You want at least one of the following before ERAS is finalized:

- Another Sub‑I in the same specialty

- A high‑responsibility elective in the same field (e.g., inpatient cards elective for IM; trauma for surgery)

- An away rotation that functions like a Sub‑I

Look at your schedule. Swap things if you have to. Drop the “fun derm elective” and pick up a real workhorse month that lets you run patients.

If scheduling is rigid, talk to your dean or clerkship office:

“My goal is to strengthen my application for [specialty]. I had a Sub‑I that I do not think represents my best work. Is there any possibility to do an additional acting internship or high‑responsibility elective in this field before ERAS certification?”

Be persistent but professional. I have seen schedules changed for weaker reasons.

3.2. Enter that next rotation with a written performance protocol

You are not going to “try harder.” You are going to change how you work.

Build a one‑page “performance protocol” for yourself with daily non‑negotiables:

Pre‑rounds

- Pre‑chart all patients the night before where possible.

- In the morning: vitals, labs, imaging, overnight events reviewed before seeing the patient.

- See patients before your senior when feasible. Formulate plan before you open your mouth.

Rounds

- Present structured, concise, with a clear assessment and plan:

- 1‑line ID

- Overnight events / subjectives

- Focused exam changes

- New key labs/imaging

- Assessment with prioritized problems and next steps with justification

- Always say: “My plan is…” not “I was thinking maybe…”

Daytime workflow

- Within 1 hour of rounds: notes on first few patients drafted; key orders in (with senior cosign).

- Volunteer: “I can call that consult / update the family / arrange the follow‑up.”

- Keep a task list and circle items when done. No dropped balls.

End of day

- Sign‑out: structured, anticipatory (“If X then Y”).

- Before leaving: “Anything else I can help with?” to resident.

Tape that protocol in your notebook. Check it twice a day until it is muscle memory.

Step 4: Fix the Core Skill Gaps That Tank Sub‑Is

From years watching students struggle, the same 5 deficits show up. Fix these and you look like a different person on the next rotation.

| Weakness | Primary Fix Focus |

|---|---|

| Disorganized workflow | Time blocking & checklists |

| Weak plans | Daily reading on all patients |

| Slow notes | Note templates & timed practice |

| Passive on team | Scripted offers & ownership |

| Unsure with patients | Standardized counseling scripts |

4.1. Disorganized: Build a real system, not sticky notes

Intern‑level work requires an intern‑level system.

- One page (or digital note) per patient with:

- Problem list

- Today’s to‑do

- Pending labs/imaging

- Consults and what you asked

- A master list for the team: name, room, DNR status, main problem, disposition plan.

Block your day:

- 06:00–07:30: pre‑rounds + quick note skeletons.

- Post‑rounds first hour: finish top priority notes and orders.

- Midday: follow up results; update plans.

- 15:00–16:00: clean up notes and loose ends.

- 16:00+ sign‑out prep.

If you used to “just react,” stop. You need a timer and blocks. Even a simple phone alarm for “check open tasks” at noon and 15:00 helps.

4.2. Weak plans: Do targeted reading, not random UpToDate spirals

The fastest way to look smarter in 2 weeks is patient‑driven reading.

Daily rule: for each patient, read:

- 5–10 minutes on:

- Current guideline or core review (UpToDate, Pocket Medicine, or an actual textbook chapter)

- At least one question: “What are the next 2–3 decisions we will make on this patient?”

Keep a small “Sub‑I Playbook” notebook:

- One page per common problem: e.g., “New CHF admit,” “DKA,” “Upper GI bleed,” “COPD exacerbation,” “Post‑op fever,” “Neutropenic fever,” “Chest pain rule‑out.”

- For each: key labs, imaging, admission orders, first‑line treatments, when to call consults, red flags.

After 2–3 weeks of this, your plans will be dramatically more intern‑like.

4.3. Slow notes: Standardize your templates and practice speed

You cannot be the person still writing notes at 4 pm.

Fix:

- Make smart templates that force concision:

- Problem‑based A/P

- Bullet points, not paragraphs

- Practice on a fake case with a timer: 10 minutes per full note, then 8, then 6.

Ask a resident:

“Can I show you one of my notes and have you tell me where I can cut fluff and get more efficient?”

Integrate their feedback that same day.

4.4. Too passive: Script your contributions

Some students truly do not know what “proactive” looks like. Here is a concrete list.

Daily, aim to:

- Volunteer for:

- First admission

- Calling at least one consult

- Updating at least one family

- Say once per day: “I can take that patient” or “I can handle that task.”

- Before defaulting to, “What do you want to do?” try, “I would suggest X because Y.”

You will overstep once or twice. That is fine. Residents would rather pull you back than drag you forward.

4.5. Uncertain with patients: Use standard scripts

If counseling conversations made you nervous, stop winging it.

Build simple scripts for:

- Code status / goals (at least for basic conversations)

- Discharge instructions for the 3–5 most common diagnoses

- Explaining new meds and major side effects

Practice them out loud. This is not theater; it is professionalism. Confidence comes after repetition, not before.

Step 5: Salvage a Decent Letter from a Weak Sub‑I (If Possible)

A less‑than‑stellar rotation does not automatically mean a bad letter. I have seen letters that say:

“They started the month somewhat tentative, but their growth over the rotation was striking. By the final two weeks, they were functioning at the level of a strong incoming intern…”

That is not fatal. In some programs, that is almost more believable than “best student ever.”

5.1. Ask selectively and strategically

You should not ask for a letter from:

- An attending who barely remembers you

- Someone who gave you clearly negative feedback

- A person famous for writing lukewarm, generic letters

You can ask if:

- They saw you improve over the month

- They know you outside this one rotation (research, clinic, teaching)

- You can articulate clearly what you worked on and how you changed

When you ask, do it in person or via a thoughtful email:

“I know my Sub‑I performance was not perfect, and you gave me valuable feedback on [X/Y]. I have been working on those areas on my current rotation by [specific actions]. If you feel you could speak to my growth and my readiness to function as an intern in [specialty], I would be grateful for a letter. If not, I completely understand and prefer you decline.”

You are giving them an honorable out. That alone filters out bad letters.

5.2. Provide a targeted letter packet

Do not send a generic CV and personal statement only. Add a one‑page progress brief:

- 2–3 bullets: “Feedback I received on Sub‑I”

- 2–3 bullets: “Concrete changes I have implemented since”

- 2–3 bullets: “Examples of improved performance on subsequent rotations”

You are handing them the arc: from underwhelming to ready.

Step 6: Shape the Story: How (and Whether) to Address This in ERAS

Do you talk about the weak Sub‑I in your application? Sometimes yes, sometimes absolutely not.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Address Directly | 25 |

| Address Briefly if Asked | 35 |

| Do Not Bring Up | 40 |

6.1. When to ignore it

You do not need to highlight it if:

- Your final grade is fine (e.g., high pass in a system where honors is rare).

- You have at least one other strong Sub‑I in the specialty with a great letter.

- There is no obvious “red flag” language in the narrative portion of the eval.

Programs see plenty of “good but not unicorn” students. They care more about your overall trajectory.

6.2. When to address it briefly

Consider a short, direct mention if:

- This was your only Sub‑I in the specialty at your home program, and

- You are applying to that same specialty, and

- There is obvious grade discrepancy (e.g., mostly honors, one “pass” Sub‑I).

Keep it factual and growth‑focused. This belongs in:

- The “Additional Information” section of ERAS or

- A very short paragraph in a secondary or supplemental statement (if allowed).

Example:

“On my initial Sub‑I in internal medicine, my performance was not at the level I expected of myself, particularly in efficiency and proactive communication. After mid‑rotation feedback, I implemented a structured task system and sought additional coaching from residents. On my subsequent acting internship in cardiology, I consistently managed 6–8 patients independently, completed timely notes and orders, and received strong evaluations highlighting these improvements.”

No drama. No excuses. Just cause, intervention, outcome.

6.3. Prepare your interview answer now

Someone will eventually ask: “Tell me about a time you struggled clinically.”

This is your script, roughly:

- Situation: “My first Sub‑I in [field] did not meet my own expectations. I was slow with notes and too reactive rather than anticipating next steps.”

- Feedback: “Midway through the month, my senior told me directly that I was not functioning like an intern yet.”

- Intervention: “I built a daily task system, standardized my notes, and asked another resident to review my workflow. On my next rotation…”

- Result: “I was handling X patients, volunteers for Y tasks, and my evaluations mention [specific positive phrases].”

- Takeaway: “Now when I feel behind, I ask for early feedback and implement concrete changes instead of hoping things will improve on their own.”

You are showing exactly what programs want: you get punched, you reorganize, you come back better.

Step 7: Protect Your Mental Game So You Do Not Repeat the Same Mistakes

If you walk into your next rotation convinced you are “the weak Sub‑I,” you will play small again. That is how self‑fulfilling prophecies work.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Underwhelming Sub-I |

| Step 2 | Specific Feedback |

| Step 3 | Targeted Skill Plan |

| Step 4 | High-Responsibility Rotation |

| Step 5 | Improved Evaluations |

| Step 6 | Coherent ERAS Narrative |

7.1. Separate identity from performance

You are not “a bad Sub‑I.” You had one month where your systems were not ready.

Plenty of excellent residents had forgettable or even bad rotations as students. The difference is they did something about it.

Write this down somewhere you see it:

“I am not stuck at my last rotation. I am training for the next one.”

Cheesy? Yes. Effective? Also yes.

7.2. Control what you can in the weeks before ERAS

Over the next 4–8 weeks, focus on three controllables:

- Deliberate practice on the next rotation (use the protocol from Step 3–4).

- Documentation of improvement: ask for mid‑rotation feedback and save any positive comments.

- One or two strong letters that see you at your best.

Stop checking Reddit threads comparing “perfect applications.” That will not make you better clinically.

Step 8: How This Actually Helps Your Match Chances

Here is the part almost no one tells you: programs care less about one mediocre Sub‑I and more about your trajectory.

I have sat in meetings where faculty say things like:

- “They started rough but finished strong. I like that.”

- “This one has clearly taken feedback and improved across the year.”

- “Not the top test scores, but the interns love working with them.”

Your job now is to engineer a clear upward slope.

| Category | Clinical Performance Level |

|---|---|

| Early Core | 60 |

| First Sub-I | 65 |

| Repair Rotation 1 | 80 |

| Repair Rotation 2 | 85 |

What that looks like on paper:

- Early cores: mixed but trending upward.

- First Sub‑I: “above expectations” but with narrative calling out specific weaknesses.

- Later Sub‑I or advanced elective: strong evals emphasizing initiative, efficiency, ownership.

- Letters: at least one that explicitly praises your response to feedback.

Programs will believe the later data more. Because it is closer to residency.

You are not trying to erase the weak month. You are trying to make it obviously outdated information.

Your Concrete Next Step Today

Do not just “think about this.” Do one specific thing in the next 30 minutes.

Here is what you do right now:

- Open a blank document titled “Sub‑I Recovery Plan.”

- Write three headings:

- Feedback I received

- Concrete changes I will make on my next rotation

- Rotations / attendings who can see me at my best before ERAS

- Under “Feedback I received,” list every critical phrase you can remember from that Sub‑I. No sugarcoating.

- Then email one senior or attending from that rotation asking for a 10–15 minute debrief using the script above.

Once that email is sent, you are not just the student who had a weak Sub‑I.

You are the one actively fixing it.