The worst residency essays are rushed in the last 10 days. Do not be that applicant.

If you give yourself 6 honest weeks, you can turn a chaotic brain dump into a tight, memorable personal statement that actually helps you match. Here is the week‑by‑week, then day‑by‑day roadmap to get you there without melting down during ERAS season.

Big Picture: Your 6‑Week Residency Essay Timeline

At this point you should not be “writing.” You should be planning.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Foundation - Week 1 | Brainstorming & story inventory |

| Foundation - Week 2 | Structure & rough first draft |

| Development - Week 3 | Major revision & narrative clarity |

| Development - Week 4 | Feedback from mentors & targeted rewrites |

| Refinement - Week 5 | Line editing, polishing, program tailoring |

| Refinement - Week 6 | Final proof, ERAS upload, contingency checks |

And here is how your effort should shift as you go:

| Category | Brainstorming & Reflection | Drafting & Revising | Feedback & Editing | Technical/ERAS Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 60 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| Week 2 | 20 | 60 | 15 | 5 |

| Week 3 | 10 | 60 | 25 | 5 |

| Week 4 | 5 | 40 | 45 | 10 |

| Week 5 | 0 | 20 | 60 | 20 |

| Week 6 | 0 | 10 | 70 | 20 |

Now we walk through each week. Then we zoom into the final 7‑day stretch.

Week 1: Brainstorm and Build Your Story Inventory

At this point you should not open a blank document titled “Personal Statement.” That is how you stare at a cursor for 90 minutes and end up on Instagram.

This week is about gathering raw material.

Days 1–2: Dump your experiences

Sit down twice for 45–60 minutes. No editing. Just list.

Create four columns on a page:

- Clinical moments

- Patients who changed you

- Challenges / failures

- Turning points toward this specialty

Under each, list actual scenes, not concepts.

Bad: “I care about underserved care.”

Better: “30‑year‑old with new CHF in hallway bed for 3 days because no insurance.”

Aim for:

- 15–20 clinical scenes

- 5–10 challenges

- 3–5 key turning points toward your specialty

Days 3–4: Identify your “through‑line”

Now you should start seeing patterns.

Ask yourself:

- What 2–3 traits keep showing up? (e.g., “I run toward chaos,” “I like slow complex puzzles,” “I am obsessed with communication errors.”)

- In one sentence: Why this specialty, not another?

Write three one‑sentence answers to each:

- Why internal medicine (or EM, surgery, etc.)

- What you are like on the team

- What you want from residency

These will become the spine of your essay.

Days 5–7: Choose your anchor story

By the end of Week 1 you should have chosen the one story that opens your essay.

Criteria:

- You remember concrete details: sounds, dialogue, room layout

- It actually changed how you saw medicine or yourself

- It connects clearly to your specialty

Test it quickly: explain that story + connection to specialty out loud in 90 seconds to a friend or your significant other. If they say, “Yeah, that sounds like you,” you are probably on track.

Week 2: Structure and Draft Your First Version

Now you write. Badly. On purpose.

Day 8: Outline in 7–8 bullet points

At this point you should know the rough arc:

- Hook: 1 anchor clinical story (short, specific)

- Zoom out: what this story revealed about you or medicine

- Brief training journey: how you got to this specialty

- Core traits: 2–3 you want programs to remember

- Evidence: 2–3 quick examples (research, leadership, work)

- What you want in a program

- Closing: tie back to opening / looking forward

Write bullet points for each section. Do not write sentences yet.

Days 9–10: Write the ugly first draft (800–1,000 words)

Open a new document. Set a 60‑minute timer. Get from start to finish without fixing anything.

Targets:

- Length: 800–1,000 words. You will cut later.

- No line editing. Zero.

- Use simple phrases like “I learned…” “I realized…” You will refine later.

Day 9: Draft half.

Day 10: Finish it and add transitions.

By the end of Day 10, you should have a complete, messy draft that a human can read from top to bottom without getting lost.

Days 11–14: Rest + light annotation

For 2 days, do not touch the draft. Your brain needs distance.

Day 13–14, read it once and mark:

- [C] = cliché (“I have always wanted to be a doctor”)

- [CONF] = confusing / unclear

- [LONG] = over‑explained

- Star the 2–3 sentences you actually like.

No rewriting yet, just diagnosis.

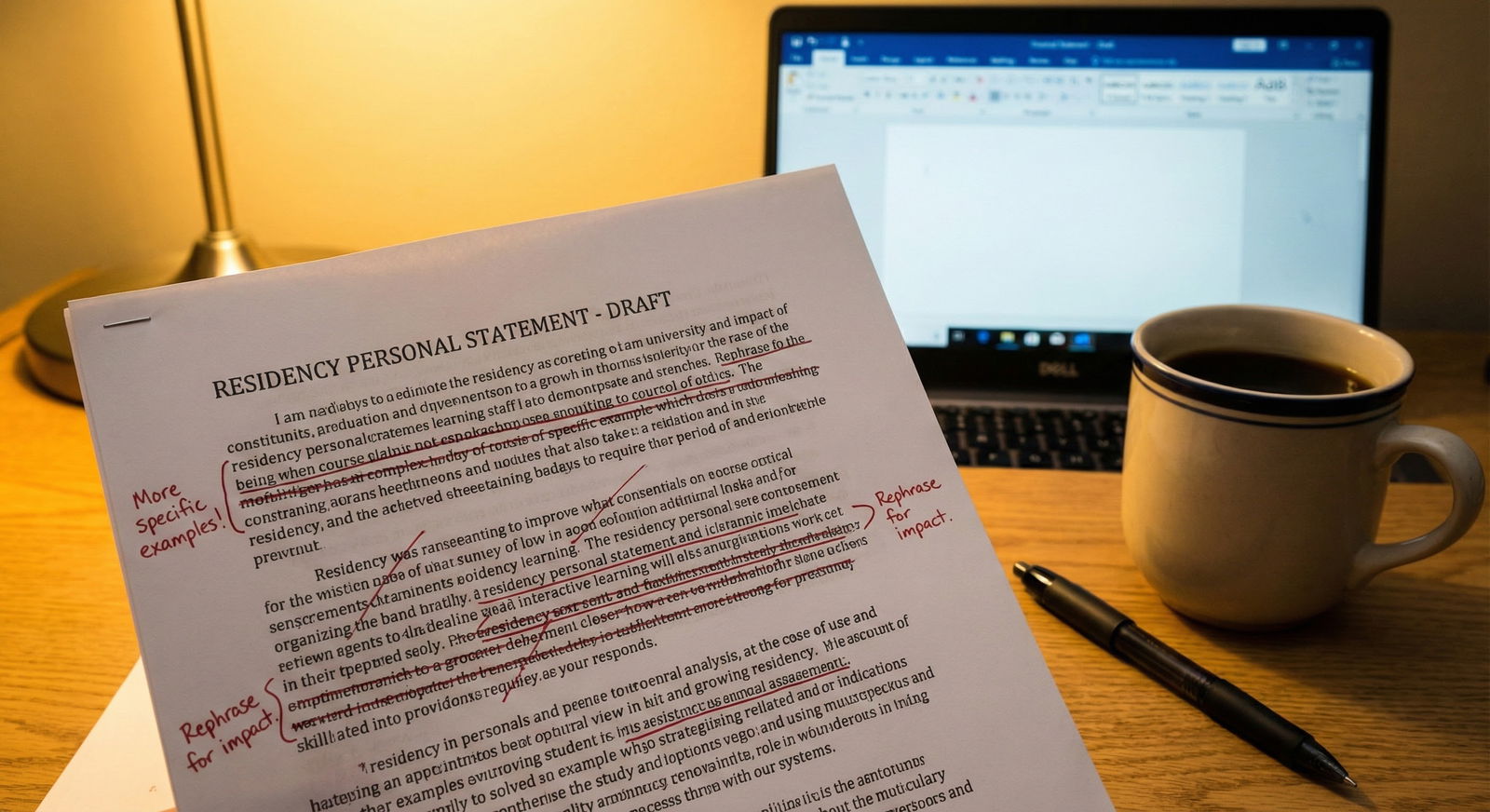

Week 3: Major Surgery – Content and Structure Revision

This is the week where the essay either becomes strong or stays generic.

Day 15: Rewrite the opening

At this point your first paragraph is probably too long and too vague.

Rules for the opening:

- 4–6 sentences, max

- Must be a scene, not a summary

- Include at least 2 concrete details (monitor alarms, the smell of chlorhexidine, the sound of the interpreter on speakerphone)

Bad:

“I have always been drawn to pediatrics because I love working with children.”

Better:

“The toddler would not stop screaming until his mother started singing the same off‑key cartoon song I had been hearing all day in clinic. We were on our third attempt at a nebulizer treatment, the fourth patient squeezed into a room built for two, with an interpreter’s voice cutting in and out on speakerphone.”

You can feel the difference. Programs do too.

Days 16–17: Tighten the middle

Focus on:

- Clear transition from your anchor story to “why this specialty”

- One paragraph that actually explains your choice (not just “during my rotation I loved…” but why)

- Remove mini‑CV sections; ERAS already has your activities

Ask of every sentence:

Does this either (1) reveal something specific about me OR (2) make my choice of specialty make more sense?

If not, cut it.

Days 18–19: Sharpen the ending

Your last paragraph should:

- Look forward (what kind of resident you will be, what you hope to grow in)

- Echo something from the beginning (tone, image, or theme)

- Mention what you want in a program in one tight sentence

Avoid:

- “I am confident I will be a great resident.”

- “Thank you for your consideration.”

- Generic mission statements (“I hope to provide compassionate, patient-centered care.” Everyone says this.)

Day 20–21: Read aloud and time it

By the end of Week 3 you should:

- Have a structurally solid, readable essay of about 750–900 words

- Be able to read it aloud in ~4–5 minutes without stumbling over clunky sentences

Reading aloud is non‑negotiable. That is where you will catch 80 percent of the awkward phrasing.

Week 4: Strategic Feedback and Targeted Rewrites

This is where many people go wrong. They either:

- Ask 8 people for feedback and end up with a Frankenstein essay, or

- Ask no one and submit a statement that sounds fine in their head and flat to everyone else.

Do not do either.

Days 22–23: Choose 2–3 readers, max

At this point you should have:

- One reader in your specialty (resident, fellow, or attending)

- One strong writer (could be outside medicine) who will be honest

- Optionally: an academic advisor / dean for big‑picture sanity check

Send them a clear request:

- What is the one thing you remember after reading?

- Does this sound like me as you know me?

- Is there anything confusing, boring, or generic?

Do not ask for line edits yet.

Days 24–25: Sift feedback and protect your voice

You will get conflicting advice. Expect it.

Your job:

- Accept feedback where 2 or more people point to the same problem (slow opening, confusing specialty explanation, too much research).

- Ignore edits that make you sound like someone else.

- Correct any red flags (arrogant tone, oversharing, professionalism issues).

Make 2–3 big changes, not 20 small ones. For example:

- Swap out your opening story for a stronger one.

- Cut an entire research paragraph that adds nothing.

- Add one paragraph that clearly explains a red flag (leave of absence, Step failure) if needed.

Days 26–28: Second full rewrite

By the end of Week 4 you should have Version 2:

- 650–800 words

- Clean structure

- Clear motivation for the specialty

- 1–2 memorable specific images

Save it as a new file. You want the ability to go back if you edit yourself into a corner.

Week 5: Line Editing, Polish, and Program Tailoring

Now you move from “good story” to “clean, professional, residency‑ready.” This is the week where you cut fat.

Day 29: Cut filler and clichés

Go line by line and hunt for:

- “Always” / “never” / “passion” / “dream” – usually fluff

- Phrases like “I realized that,” “I think that,” “In order to” – usually can be shortened

- Repetitions of the same trait (if you claim “teamwork” 4 times, you sound insecure)

Turn this:

“I have always had a passion for internal medicine because it allows me to think critically about complex patients.”

Into this:

“Internal medicine gives me what I like most: complex patients and time to think.”

Same idea. Less noise.

Day 30: Check balance of content

Quick self‑audit:

| Section Type | Target % of Essay |

|---|---|

| Clinical stories / scenes | 35–45% |

| Reflection & motivation | 30–40% |

| Concrete evidence (research, leadership, teaching) | 15–20% |

| Program fit / future goals | 10–15% |

If 70 percent of your essay is just feelings and abstract values, you need more concrete evidence. If 70 percent is CV regurgitation, you need more reflection.

Days 31–32: Sentence‑level cleanup

Now you zoom in:

- Vary sentence length. If you have five 25‑word sentences in a row, chop some.

- Replace weak verbs (“was involved in,” “helped with”) with specific ones (“led,” “designed,” “organized”).

- Remove formal fluff: “In conclusion,” “I would like to state that.”

Read aloud again. Fix where you stumble.

Days 33–35: Light tailoring for different program types

You do not write a different personal statement for every program. That is how people burn out. But you can create 2–3 variants if needed:

- Academic‑leaning version: slightly more emphasis on research/teaching

- Community‑leaning version: more emphasis on continuity, underserved, efficiency

- Highly competitive specialty: a bit tighter, slightly heavier on excellence and resilience

Keep 90 percent of the essay identical. Adjust:

- 2–3 sentences about program fit and future goals

- A line or two emphasizing what you value (research vs. continuity clinic vs. procedures)

Name your files clearly: “IM_PS_Academic_v3,” not “finalFINAL2.docx”.

Week 6: Final Week – Proof, Upload, and Sanity Checks

This is where people sabotage themselves with last‑minute “inspirations.” Resist the urge to rewrite the whole thing at 1 a.m.

Day 36: Professionalism and red flag review

At this point your content should be 95 percent set.

Do one focused read for:

- HIPAA: zero identifiable patient info (no names, unique diagnoses + locations that can pinpoint someone)

- Tone: confident but not arrogant, honest but not oversharing

- Red flags: if you have a major issue (leave, failure, gap), is it addressed briefly, factually, and with growth?

If you are unsure about how you addressed a red flag, run just that paragraph by a dean or trusted faculty. Do not crowdsource it to Reddit.

Day 37–38: Final outside proofread

Find one person who has not seen the essay yet.

- Ask only for typos, grammar, and clarity of a few confusing lines.

- Tell them: “Please do not suggest big structural changes unless something is truly broken. I am at the final stage.”

You are protecting your sanity here.

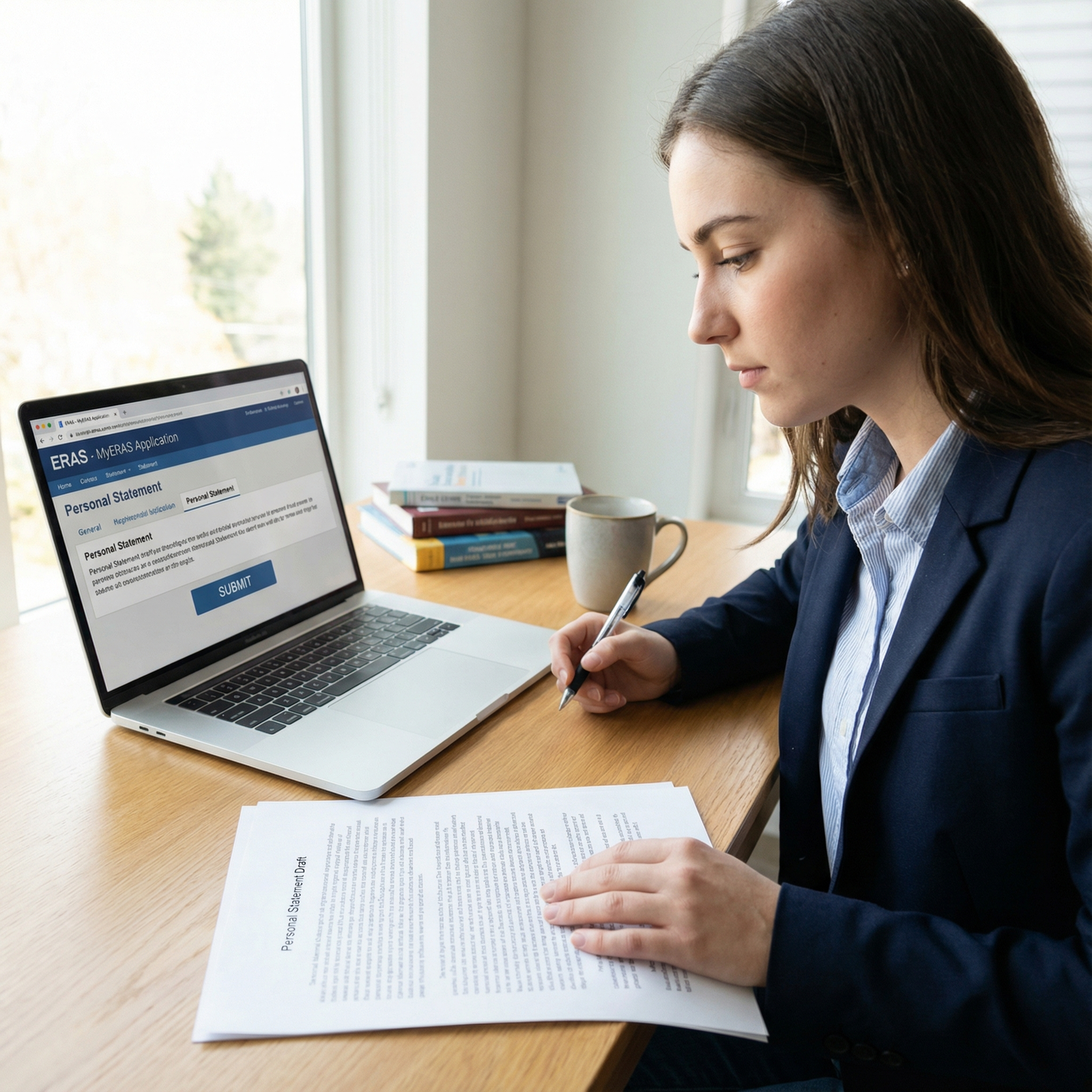

Day 39: Format for ERAS

ERAS can wreck your formatting if you are careless.

Quick checklist:

- Paste into a plain text editor first (e.g., Notepad) to strip weird formatting.

- Check paragraph spacing – 4–6 paragraphs, with clear line breaks.

- Confirm character count and line length look reasonable in the ERAS preview.

Day 40: Create final labeled versions

You should now have:

- 1 master personal statement file saved safely (cloud + local)

- 1–2 variant texts if you are tailoring for program types

- Clear mapping of which statement goes to which program set

Pro tip: Create a simple spreadsheet:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Single PS | 60 |

| Two Variants | 30 |

| Three Variants | 10 |

Most people should be in the first two categories.

Days 41–42: Upload and final quiet read

Plan uploads like a clinical task, not like a side chore.

- Upload the statements you plan to use into ERAS.

- For each program batch (e.g., “academic IM”), double‑check that the correct statement is assigned.

- Do one last slow read in the ERAS preview itself. People miss typos in Word that suddenly scream at them in the ERAS font.

Then stop. No last‑minute “major insight” rewrites. That is how errors sneak in.

Optional: Compressing This Plan If You Are Behind

If you are reading this with 3 weeks to go, you can still salvage things, but you have to be ruthless.

Condensed version:

- Days 1–2: Do all of Week 1’s brainstorming in two long sessions.

- Days 3–5: Outline + full first draft.

- Days 6–9: Major revision (combine Weeks 3 + 4); get feedback from one specialty mentor and one strong writer.

- Days 10–14: Line editing, polish, and ERAS upload.

What you cut:

Extra feedback cycles

Fancy tailoring for different programs

What you do not cut:At least one real revision

One external proofread

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. How long should my residency personal statement actually be?

Most strong statements land between 650 and 800 words. ERAS allows more, but if you are pushing 1,000+ you will almost always drift into repetition or mini‑CV mode. Programs read dozens of these in a sitting. Give them something tight, specific, and readable in under 5 minutes. If you cannot cut it under 850 words, you likely have too many stories or you are over‑explaining.

2. Should I write different personal statements for every program?

No. That is a great way to introduce errors and burnout. For almost all applicants, 1 main personal statement is enough, plus maybe 1 alternate version if you are applying across quite different settings (e.g., mostly community with a few very academic programs) or across two specialties. Instead of rewriting the whole thing, adjust 2–3 sentences about your future goals and what you seek in a program. The core story and voice should stay the same.

3. How honest should I be about weaknesses or red flags?

Direct and concise. Not confessional. If you have a clear red flag (Step failure, leave of absence, professionalism issue), a short paragraph is usually appropriate. State what happened in plain language, take responsibility where appropriate, describe concrete steps you took to address it, and briefly note how you have performed since. Then move on. Do not let the entire essay orbit around your weakest moment. Programs want evidence you understand the issue and have grown, not a page of self‑critique.

Two closing points. Start earlier than your classmates think is necessary. And treat your personal statement like a clinical note that actually matters: clear story, relevant details, clean assessment, and a plan that makes sense.