The worst way to handle a Step failure in your personal statement is to pretend it did not happen.

If you have a Step 1 or Step 2 CK failure, programs already know. It is on your transcript. The question is not “Will they see it?” The question is “What story are they going to attach to it — yours or their own?”

You are writing to control that story. Let’s do it properly.

Step 1: Decide if you should address the failure in the personal statement at all

Not every Step failure belongs in the main personal statement. Sometimes it should be:

- In the personal statement

- In the ERAS “Education/Training Interruptions / Adverse Action” section

- In a secondary/”red flag” essay if a program asks

- In none of the above, and addressed only if brought up at interviews

Here’s a blunt framework.

| Situation | Where to Address It |

|---|---|

| Single fail, then strong pass on next attempt and overall strong app | Optional brief mention in PS or just ERAS explanation box |

| Fail plus big upward trend (e.g., 190 → 245) | Smart to mention in PS to frame growth |

| Fail plus mediocre retake and other academic issues | Must control narrative in PS + ERAS box |

| Multiple exam failures | Definitely in PS, ERAS box, and be ready in interviews |

| Fail directly linked to major life event (illness, death, etc.) that shaped you | PS is often the best place, if you connect it to growth, not just excuses |

Hard rule:

If your Step failure is likely to be a primary screening knock-out for your chosen specialty, you almost always need to address it directly in your personal statement. You are asking them to pause before auto-discarding your file.

If you are applying to a less numerically cutthroat specialty, with:

- Only one failure

- A solid retake

- Strong clinical evals and letters

…you can sometimes keep it out of the main essay and use the ERAS explanation box instead. But then the explanation must be clean and tight.

If you’re unsure which camp you fall into, assume you should address it. Silence looks worse than a concise, mature explanation.

Step 2: Understand what PDs actually look for when they see a failure

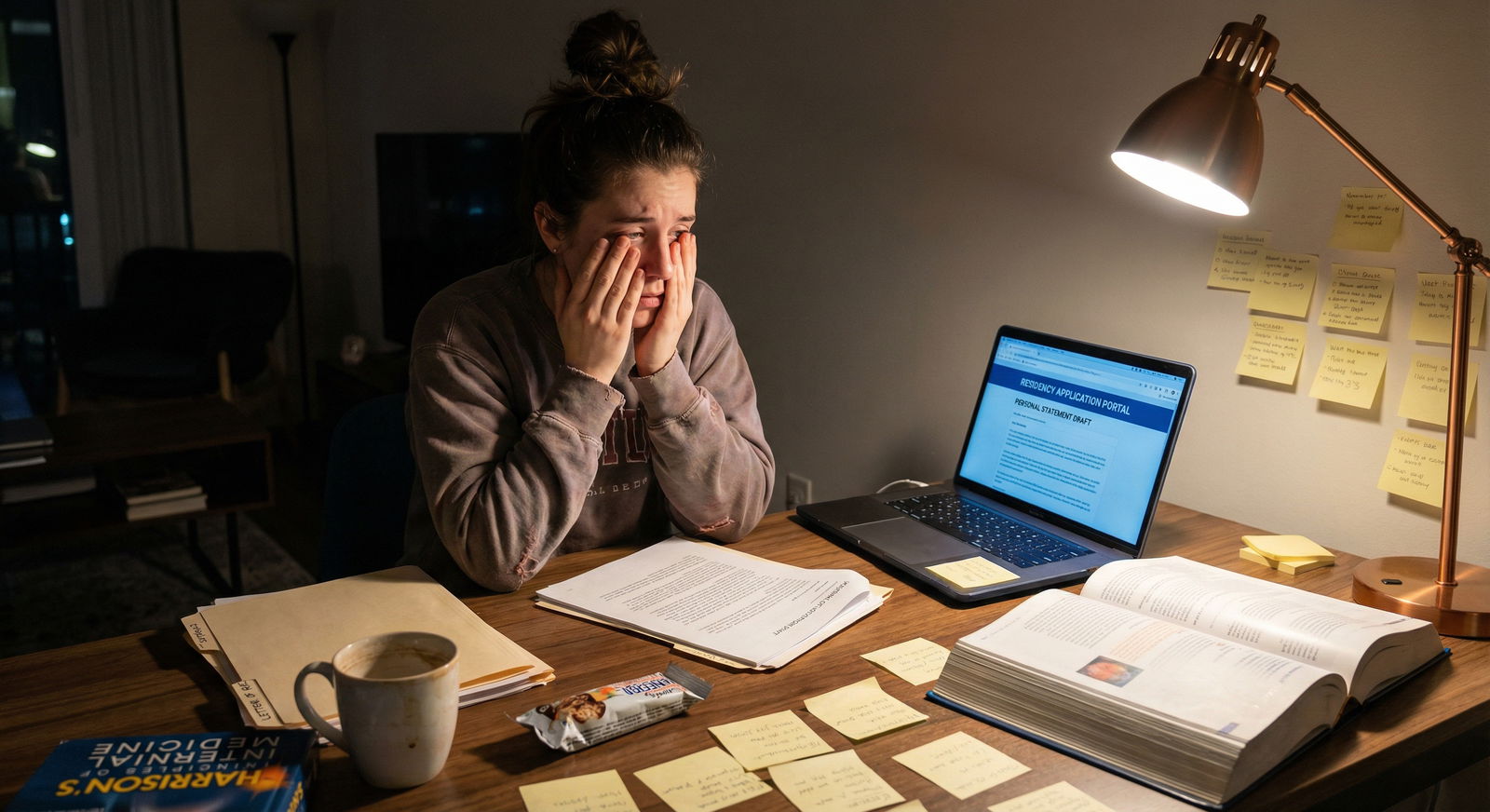

Program directors are not sitting in a dark room trying to fail people for fun. What they care about is risk.

When they see “Fail” next to Step 1 or Step 2, their brain usually runs through something like this:

- Is this person going to struggle with in‑training exams?

- Are they going to jeopardize board pass rates for the program?

- Are they unreliable? Disorganized? Burned out?

- Are they going to need constant remediation?

- Is there any sign they learned from this or is it denial and excuses?

Your personal statement’s job is to answer these silently asked questions before they reach the end of page one.

You want to show three things, clearly:

- You understand what happened (no fog, no denial).

- You changed something concrete.

- The new pattern is sustained and aligned with success in residency.

Do that, and the failure becomes a data point, not a death sentence.

Step 3: Choose the right placement in the essay

Where you put the explanation matters.

Two bad options:

- Opening your statement with: “I failed Step 1 because…”

- Burying it in one vague sentence at the bottom: “I faced academic challenges during medical school, but I have grown from them.”

Both signal poor judgment.

Here’s a structure that works in real life:

- Hook/intro about why this specialty and who you are now

Show them you are more than a test result. 2–3 short paragraphs. - Middle section with the failure + reflection + change

One focused paragraph, two at most. - Evidence section — clinical, research, leadership that show growth

- Closing — forward-looking, confident, grounded

You want the Step explanation in the middle third, once they already see you as a potential colleague, not just a score.

Step 4: What to actually say (and what to avoid completely)

You need one clean, direct paragraph. Not a sob story. Not a legal defense.

Here’s the basic skeleton:

- One sentence stating the fact (yes, explicitly).

- One to two sentences explaining the cause, anchored in your own responsibility.

- Two to three sentences on concrete changes you made.

- One to two sentences tying those changes to actual improved outcomes.

Let’s build this out with real language.

1. State the fact plainly

Examples:

- “During my third year, I failed Step 2 CK on my first attempt.”

- “I failed Step 1 on my first attempt, then passed on my second with a score of 231.”

No euphemisms like “I did not initially achieve a passing score.” That sounds like you are dodging reality.

2. Describe cause without excuses

Your explanation should feel like this: “Here’s what went wrong, here’s what I did wrong, here’s how I fixed it.”

Bad:

“I was going through a difficult time with family responsibilities and the test did not reflect my true abilities.”

Better:

“While preparing for Step 1, I underestimated the volume and depth of material and relied too heavily on passive review. I also struggled to balance a heavy family responsibility with consistent practice questions. The result was a failed first attempt.”

See the difference?

You can mention life events, but they sit next to your own misjudgment and poor strategy, not instead of it.

3. Spell out what changed — concretely

Program directors do not want to hear your new “mindset.” They want to hear new behaviors.

Examples of actual changes that matter:

- Switched from passive reading to daily practice questions with review

- Created a weekly schedule with protected time, tracked with specific goals

- Sought faculty or learning specialist support and stuck with it

- Studied in small groups with accountability

- Adjusted test‑taking strategies: timing practice, reviewing wrong answers deeply

You should be able to write a sentence like:

“I met with our learning specialist, shifted from passively reviewing notes to doing 80–100 UWorld questions per day with detailed review, and built a weekly schedule that I shared with a mentor to maintain accountability.”

That is believable. That sounds like someone I can remediate if I have to.

4. Show actual, measurable results

Here’s where you put your money where your mouth is.

Examples:

- “On my second attempt, I passed Step 2 CK with a score of 245.”

- “Since then, I’ve passed all subsequent exams on the first attempt, including Step 2 CK (238), and have scored above the 80th percentile on in-house shelf exams in internal medicine and surgery.”

- “These changes translated to consistent high marks in my clinical evaluations, with particular praise for preparation and reliability.”

If Step scores are weak overall, lean harder on shelf exam improvement, clinical comments, and concrete feedback. But don’t pretend your later Step was stellar if it wasn’t. Just show direction and stability.

Step 5: Examples of strong vs. weak paragraphs

Here’s where people mess this up. Let me show you what admissions readers actually see every cycle.

Weak, common version

“During my second year, I faced significant personal challenges that impacted my ability to perform at my usual level, and as a result, my Step 1 performance was not what I had hoped. However, I have grown from this experience and learned the importance of perseverance, time management, and self-care. I believe these lessons will make me a stronger resident.”

Translation to PDs: “I failed. I will not tell you how or why. I’ve attached some inspirational words. Please trust me.”

Stronger, specific version

“I failed Step 1 on my first attempt. I underestimated the exam’s difficulty and overestimated how much content I could retain through passive reading and highlighting. I also tried to manage a significant family responsibility without adjusting my study plan. After failing, I met with our school’s learning specialist, shifted to doing 80–100 timed practice questions per day with detailed review, and scheduled shorter, focused study blocks that I protected more carefully. On my second attempt, I passed with a score of 231, and I carried these changes into my clinical year, where I passed all shelf exams on the first attempt and scored above the 75th percentile in internal medicine and surgery. This experience forced me to build a more disciplined and efficient approach to learning that I now bring to every rotation.”

That paragraph:

- States the fact

- Owns the mistake

- Shows specific changes

- Links to actual results

- Ends on a competence note, not a sad note

That is exactly what you are aiming for.

Step 6: Tailor the explanation to your specialty and context

Different specialties care about different angles. The Step failure explanation should quietly support your fit for that specific field.

For highly competitive specialties (derm, rads, ortho, ENT, etc.)

You are climbing uphill. You cannot be vague. Your angle is: “Yes, this is a red flag. Here’s why it should not define me.”

You need:

- Hard numbers showing improvement (if you have them)

- Strong evidence of excellence elsewhere: research, honors, letters

- Language that signals resilience under pressure and high-level performance

For example:

“The same structured approach I used to improve from a failing Step 1 attempt to a 246 on Step 2 CK is what I brought to the dermatology electives I completed, where attendings consistently trusted me to prepare concise, high-yield presentations on complex patients.”

Link the growth to how you function in a demanding environment.

For core specialties (IM, FM, peds, psych)

They care about:

- Reliability

- Growth

- Ability to pass boards eventually

- How you function on busy services

You can lean more into:

- Consistent clinical performance

- In‑training exam potential

- Feedback from attendings about preparedness and follow-through

Example angle:

“Since that failure, my faculty have consistently commented on my preparation and reliability on the wards. I have learned to front-load reading before each rotation, use checklists for follow-up tasks, and ask early when I am unsure — habits that grew directly out of that difficult exam experience.”

Step 7: Avoid these 6 common mistakes that torpedo credibility

If you remember nothing else, remember this list. These are the things that make PDs roll their eyes and move on.

Blaming the exam format or “bad luck”

“I had a bad test day” is not a story. It is an excuse.Over-explaining the personal tragedy

A sentence or two, max. This is not a grief essay. It’s an application to a job.Turning it into a hero’s journey epic

One failed test is not a Greek tragedy. Keep the tone calm, matter-of-fact.Ignoring it completely when it clearly matters

If you have multiple failures or a failure plus a weak retake, silence reads as avoidance.Conflicting with your ERAS explanation

If you mention depression, illness, or a leave of absence one place and not the other, it looks sloppy or dishonest. Align the narratives.Ending on the failure rather than the growth

The last sentence of that paragraph should be about what you do well now, supported by evidence.

Step 8: Integrate the failure into a bigger narrative of who you are

Your personal statement is not “The Story of My Step Failure.” That’s the trap.

It is:

- “Why I’m drawn to [specialty]”

- “How I work with patients and teams”

- “How I handle pressure, complexity, and learning”

- “What kind of resident I will be at 2 a.m. on call”

The Step failure should be one plot point that supports the bigger story: you learned how to adapt, self-correct, and show up better.

Here’s how you can stitch it in:

- Start with a short clinical scene or rotation that solidified your specialty choice.

- Move into what you value in that work: thinking, continuity, procedures, whatever fits.

- Pivot: “I did not always approach my work with the discipline I now bring.”

- Insert the Step paragraph.

- Show how the same skills you developed after the failure show up in your patient care, research, or team work.

- Close by connecting those skills to what you want in residency.

That way, the failure is proof of a trait (growth, resilience, adaptability), not just a confession.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Board Pass Risk | 90 |

| Work Ethic | 75 |

| Reliability | 70 |

| Stress Tolerance | 65 |

| Honesty | 50 |

Step 9: Quick rewrite drill you can do right now

If you already wrote a draft, do this:

- Find every sentence where you allude vaguely to “challenges,” “obstacles,” or “setbacks.”

- Circle any that could refer to the Step failure but never say so directly.

- Pick one paragraph where you’ll put your explicit Step explanation.

- Replace the vague lines with:

- One clear sentence stating the failure

- Two sentences on cause + your role

- Three sentences on changes + results

Read that paragraph out loud. If it sounds like:

- A calm attending explaining a case

- Not a defense attorney giving a closing argument

…you’re in the right zone.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step Failure |

| Step 2 | Maybe ERAS box only |

| Step 3 | PS + ERAS box |

| Step 4 | PS + ERAS + interview prep |

| Step 5 | Explain briefly in mid-PS |

| Step 6 | Severity? |

FAQs

1. Should I mention actual Step scores in my personal statement?

If the score demonstrates clear improvement (e.g., failed Step 1 → 245 on Step 2), including numbers can help. If the retake score is barely passing, you can simply say “passed on the second attempt” and highlight shelf exams, clinical evaluations, and letters as your evidence of growth. Do not lie. But you are not required to repeat numbers the PD can already see on the score report.

2. What if my failure was mostly due to depression, anxiety, or another mental health issue?

You can mention this briefly and clinically: “During that time, I was struggling with untreated depression, which affected my concentration and consistency. I sought treatment, started therapy/medication, and since then have passed all subsequent exams on the first attempt and maintained strong clinical performance.” Do not turn the statement into a detailed psychiatric history. Focus on stability, treatment, and sustained performance since then.

3. Is it better to put the explanation in the ERAS “adverse action” box instead of the personal statement?

Use the ERAS box for the bare facts. Use the personal statement if the failure is a significant part of your academic story and you need more room to show reflection and growth. For many applicants with a single failure and clear improvement, a short ERAS explanation plus a one-paragraph nod in the personal statement is ideal. If your failure is minor and your retake is very strong, the ERAS box alone may be enough.

4. How long should my Step failure paragraph be?

Aim for 4–7 sentences. If you are over 10, you are probably over-explaining or drifting into emotion and backstory that belong elsewhere. Remember: one tight paragraph in the middle third of your statement is usually enough. The rest of the essay should be about your specialty fit and who you are as a future resident.

5. What if I am still embarrassed and feel like the failure defines me?

You do not have to “feel good” about the failure to write effectively about it. You just have to be honest, specific, and forward-looking. The people reading your application have seen stellar residents with early failures and high scorers who crumble on call. Your job is not to erase the failure; it is to prove that it taught you how to adjust and perform. Open your draft right now and write one blunt sentence that starts, “I failed Step [X] because…” and finish it as truthfully and concretely as you can. That’s your starting point.