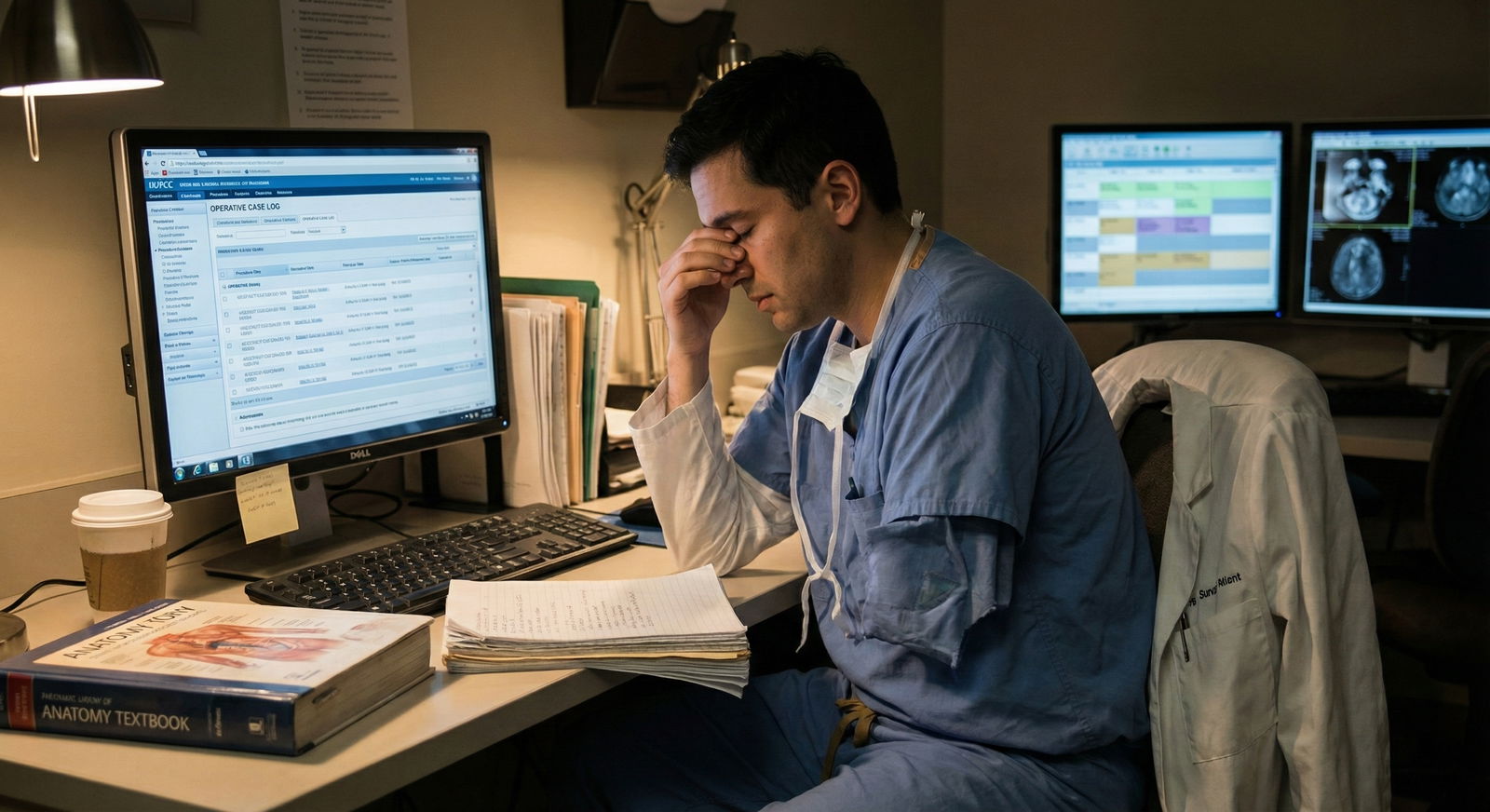

It is 7:02 a.m. You are outside OR 4, already scrubbed, mask on, double-gloved. You finally got on this high-volume trauma rotation that everyone says “makes or breaks” surgical applicants. The attending walks in, nods once, and says, “Any questions before we start?”

You open your mouth.

You ask about the hospital’s new EMR roll-out and how it affects documentation.

The attending stares at you for half a second longer than feels safe, says, “That is for later,” and turns straight to the resident: “Let’s go. We are behind.” Three days later, you are still somehow “covering the floor” while your classmates are getting lines and first assists in the OR.

You did not just have bad luck.

You asked the wrong questions. At the wrong time. On the wrong rotations.

And you quietly lost OR time because of it.

This happens over and over to students who think they are being “curious,” “engaged,” or “big-picture minded.” On some rotations, you can get away with that. On surgical case–volume rotations, it can cost you actual cases.

Let us walk through where people screw this up, how attendings and residents really interpret your questions, and how to protect your OR time before you accidentally talk yourself right off the schedule.

The Rotations Where the OR Is the Currency

Not all rotations punish bad questions equally. Some just tolerate you. Some sideline you.

On surgical case volume–heavy rotations, OR time is:

- A reward

- A finite resource

- A signal of trust

Get this wrong and you stop being “the helpful student” and become “the student I do not want in my room.”

The highest-risk rotations for losing OR time by asking the wrong questions:

- Trauma surgery

- General surgery (especially high-volume community or county hospitals)

- Vascular surgery

- Orthopedic trauma

- Surgical oncology on heavy case days

- Transplant surgery

- Cardiac surgery

These rotations are built around throughput. Time is blood. Literally.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| OR Efficiency | 95 |

| Teaching | 70 |

| Documentation | 60 |

| Research Talk | 30 |

| Tech/AI Talk | 20 |

You need to understand that hierarchy of priorities. If your questions do not match the priority of that moment, you signal that you do not get it. And people do not bring you to their OR if you do not “get it.”

The Classic “Wrong Question” Traps That Quietly Get You Benched

Let me be blunt. Certain questions, on certain rotations, instantly label you as:

- Clueless

- Inefficient

- High-maintenance

Here are recurring patterns I have watched destroy students’ OR access.

1. Big-Picture / Future-of-Medicine Talk… At 7:10 a.m. Turnover

Wrong timing, wrong topic.

On trauma or high-volume general surgery, asking:

- “How do you see AI changing surgical training?”

- “What do you think about remote robotic surgery in the next decade?”

- “Where do you think surgery will be with VR simulators?”

…while anesthesia is trying to intubate, the nurse is scrambling to get instruments opened, and the attending is three cases behind — is a fast way to mark yourself as out of touch with reality.

Those are not bad questions. They are just catastrophically mis-timed on certain services.

What the attending hears is:

“I do not know that today is about getting through 10 cases safely and on time. I would like to philosophize while everyone else is sprinting.”

Once that narrative forms, you know what happens?

You become the student they “keep on the floor for dispo issues” while your classmate who shuts up and holds retractors gets pulled into the next emergent lap chole.

2. Self-Centered Questions About Your Career… During Setup

Another killer.

These sound like:

- “What do you think my chances are for your program with a 238?”

- “How many letters do I need to match here?”

- “Do you think doing research with you would help my application?”

Again, all legitimate questions. Just not in the 90 seconds before incision on a 4-case morning.

This tells the team:

- You are more focused on yourself than the patient.

- You are not reading the room.

- You do not understand that OR setup time is precious cognitive bandwidth.

Result: you lose the “default invite” into add-on cases. Your future-of-medicine curiosity did not hurt you. Your timing did.

3. Overly Detailed Pathophysiology Right as They Are Cutting

You finally got into a vascular case. You are at the table. Attending is prepped, time-out is done, knife is in hand. You decide now is the time to ask:

- “Can you walk me through the detailed molecular pathway of atherosclerosis in diabetics?”

- “Can we talk about the newest trials on endovascular vs open for these lesions?”

Sweet idea. Wrong context.

On trauma, ortho trauma, vascular, transplant — early incision time is about:

- Landmarks

- Safety

- Critical steps

- Efficient flow

You want to be the student who asks:

- “What is the most dangerous part of this dissection?”

- “If this went sideways, what is the bailout move?”

Those questions show you are thinking like a surgeon in this case, today. That gets you more teaching and more time in the room. Not less.

How Attendings Actually Sort Students in Their Heads

Attendings and senior residents do not have a written rubric. They have mental shortcuts. I have heard versions of these verbatim in call rooms.

After a few cases, you are usually mentally sorted into one of three categories:

High-yield in the OR

- Asks sharp, brief, case-relevant questions.

- Helps with flow.

- Does not derail turnover.

- Learns quickly and does not need constant re-explanation.

Neutral presence

- Does not help much.

- Does not hurt much.

- Usually allowed in OR if there is space and no logistics crunch.

Flow disruptor

- Asks long, off-topic questions at the worst times.

- Needs repeated reminders about sterile field, position, tasks.

- Pulls attention away from the operation.

Guess which category quietly stops getting called for last-minute add-on cases?

Here is how different student behaviors tend to correlate with where you end up:

| Student Type | Typical OR Access Outcome |

|---|---|

| Case-focused questioner | Frequently invited, first assist |

| Silent but helpful | Regular OR presence, simple roles |

| Big-picture talker | Infrequent invites, floor-heavy |

| Self-focused applicant | Seen as transactional, limited OR |

| Efficiency-disruptor | Actively avoided in busy cases |

Once you are tagged as “flow disruptor,” it is very hard to dig out of that hole during a short rotation.

The Single Biggest Mistake: Confusing “Smart” Questions With “Good” Questions

Medical students are taught to ask “good questions.” On basic science rotations, that means:

- Broad

- Nuanced

- Exploratory

- Often theoretical

On surgical case–volume rotations, a “good” question is different. It is:

- Short

- Immediately clinically relevant

- Tied to the step happening right now

- Not delaying a decision or step

The mistake: assuming the standard “smart question” that impresses a PhD in conference will impress a trauma attending in the middle of a massive transfusion.

Example contrast:

Bad-time “smart” question during emergent ex-lap:

- “How do you think organ allocation policies will change with ex vivo perfusion in the next decade?”

That is a conference question.

Good, OR-appropriate question:

- “In this patient, what findings would push you to damage-control rather than definitive repair now?”

Same brain. Different setting. Only one of those keeps you seen as an asset in a time-pressured OR.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Case-Focused Question | 90 |

| Logistics Question | 70 |

| Career Question | 40 |

| Future-of-Medicine Question | 30 |

| Random Trivia Question | 10 |

Rotations Where the Wrong Question Hurts You the Most

Let us get very concrete.

Trauma Surgery

High-risk wrong questions:

- “How did COVID permanently change trauma patterns?”

- “What do you think about wearable data in trauma triage in the future?”

When you should be asking:

- “What injury pattern are you most worried about in this mechanism?”

- “At what point in resuscitation do you pull the trigger on the OR?”

Lose credibility in trauma, and you become:

- The student babysitting the trauma bay computer.

- Not the one doing the thoracotomy retraction at 3 a.m.

Ortho Trauma

High-risk wrong questions:

- “Where do you see robotics going in orthopedics?”

- “What is your opinion on outpatient joint replacement expansion?” (during a 4-case fracture day).

Better questions for case volume rotations:

- “For this fracture, what makes you choose nail vs plate?”

- “What reduction pitfall do residents miss most early on?”

Transplant Surgery

High-risk wrong questions:

- Detailed policy debates about organ allocation.

- Philosophical questions about xenotransplantation.

Good questions:

- “For this donor quality, what are your main intraoperative concerns?”

- “If the graft looks marginal on reperfusion, what adjustments do you make in the next hour?”

Transplant teams remember who stayed laser-focused on today’s graft versus who wanted to talk about pig kidneys mid-anastomosis.

High-Volume Community General Surgery

These places can be gold mines for case numbers. And graveyards for students who do not understand efficiency culture.

High-risk wrong questions:

- “Is your hospital planning to adopt the new robotic platform?” during a stacked lap chole day.

- “How is hospital consolidation affecting surgical autonomy?” when there are five add-on cases on the board.

Better questions:

- “In this case, what finding in the triangle of Calot would make you convert early?”

- “What step in this hernia repair most impacts recurrence in your experience?”

Timing: The Part No One Teaches You and Everyone Judges You On

You cannot just have the right type of question. You need the right timing.

Let me break down when it is dangerous versus safe to ask “big” or “future-of-medicine” questions.

Red Zone: Do Not Ask Big/Off-Case Questions

Avoid non-essential questions during:

- First 10 minutes of case setup and incision

- Critical dissection steps (you can feel it — everyone goes quiet)

- Rapid blood loss / any hemodynamic instability

- Multi-case back-to-back lists when turnover is under pressure

- When the attending’s answers get shorter and more clipped

In the red zone, your questions should be:

- Short

- Directly related to the current step

- Focused on safety, anatomy, or decision-making

Yellow Zone: Caution, But Possible

You can ask slightly broader, but still case-linked questions:

- During skin closure

- During decently stable, repetitive parts of a long case

- While waiting for pathology/frozen section

- During a lull while anesthesia is adjusting things but the surgeon is not scrubbed

Even here: tie it to this patient, this operation.

Green Zone: Where Future-of-Medicine Questions Actually Work

This is where you stash your AI, robotics, VR, and policy questions:

- Post-op debrief in the OR while cleaning up and briefing the next case

- In the surgeon’s office between cases when they are visibly relaxed

- On call at 2 a.m. when it is quiet, charts are done, and they are in story-telling mode

- At the end of the day when you stop by to say thank you

This is when a question like:

- “How do you see AI affecting intraoperative decision-making in the next 10 years?”

…can actually spark a great conversation. And mark you as thoughtful, not naïve.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | About to ask a question |

| Step 2 | Red Zone |

| Step 3 | Yellow Zone |

| Step 4 | Green Zone |

| Step 5 | Ask only brief, case-specific questions |

| Step 6 | Ask case-linked, slightly broader questions |

| Step 7 | Ask future-of-medicine or career questions |

| Step 8 | What phase is the case in |

The Subtle Logistics Questions That Save — Not Cost — You OR Time

Not every “non-clinical” question is bad. Some actually buy you trust and more cases. The trick is: they must be about helping the service, not satisfying your own curiosity at a bad time.

Good logistics questions (asked outside the red zone):

- “For tomorrow’s cases, what time do you want me here and what should I pre-read?”

- “For your big cases, do you prefer I see the patient pre-op and present to you, or just read the chart?”

- “If the OR schedule shifts, what is the best way for me to find where you are?”

These tell the resident/attending:

- This student is thinking like part of the team.

- This student might actually make my day smoother.

Those are the ones they go looking for at 4 p.m. when an add-on case appears.

How to Protect Your OR Time: Concrete Do’s and Don’ts

Let us be painfully clear.

Do This

Front-load your curiosity with pre-reading.

- Read about the procedure the night before.

- Look up 1–2 key decision points or complications to ask about — when appropriate.

Start the day with one logistics question, not a manifesto.

- “Is there anything specific you want me to focus on learning in the OR today?”

- Short. Respectful. Shows you are here to help, not to perform curiosity theater.

During cases, default to “watch first, then ask one targeted thing.”

- Example: after they finish a critical step and things calm for 20–30 seconds.

- “For this step you just did — what is the most common mistake learners make?”

Save “future of medicine” questions for calm, off-OR moments.

- Ask at the end of the day:

- “I read about AI for surgical video review. Do you think that will change how residents are trained?”

- Ask at the end of the day:

Defer self-focused, application questions unless invited.

- If the attending asks, “What are your career plans?” you can follow up later:

- “When you have a moment sometime this week, I would love your honest take on how to strengthen my application for this field.”

- If the attending asks, “What are your career plans?” you can follow up later:

Do Not Do This

- Do not launch into a policy/AI/future-tech question in the first 5 minutes of a case.

- Do not ask multi-part, paragraph-length questions when everyone is clearly busy.

- Do not turn every OR into an interview about your career.

- Do not assume because one attending liked a certain style of question that everyone will.

The “One-Question Rule” That Keeps You Safe on Any Surgical Rotation

If you remember nothing else, use this:

The One-Question Rule:

On busy surgical case-volume rotations, aim for one high-quality, case-specific question per case during the operation. Save everything else for before/after.

Criteria for that one question:

- Related to a step that just happened

- Brief (you should be able to say it in one breath)

- Answerable in under 30 seconds

- Improves your understanding of decision-making or critical anatomy

If the attending is talkative and invites more, fine. But your baseline is conservative. You want them to think, “This student only speaks when it matters.”

Those are the students who do not lose OR time. They gain it.

Your Action Step Today

Open your rotation schedule. Pick the most OR-heavy, case-volume–driven service you will be on (or are on now). For tomorrow’s cases, do this:

- Look up the procedure(s).

- Write down:

- One case-specific question you could ask during the operation.

- One future-of-medicine or career question you will deliberately save for after cases or at the end of the day.

Then stop. Do not add a third, fourth, fifth question.

You are not trying to sound impressive.

You are trying to stay in the room.