The story we tell about disability in medical training is statistically false. The data show far more trainees have disabilities than are actually using accommodations, and the gap is not a rounding error. It is a chasm.

You want numbers, not slogans. Let’s walk through what we actually know: how many medical students and residents report disabilities, how many get accommodations, what types they use, and where the pipeline breaks.

The Big Picture: Prevalence vs Accommodation Use

Across U.S. higher education, about 19–21% of undergraduates report a disability. Medical education pretends it lives in a different universe. It does not.

Medical students: who reports a disability?

Best available national data (largely from AAMC-linked and research consortia work between 2016–2022) consistently land here:

- Roughly 4–7% of U.S. allopathic medical students formally disclose a disability to their institution.

- In osteopathic schools, estimates are slightly higher, around 7–10%.

I have seen school-level reports swinging from under 1% to over 15%, which tells you culture and policy, not biology, drive most of the variation.

Breakdown by type among students who do disclose (approximate pooled percentages; numbers vary a bit by year and sample):

- Learning disabilities (including ADHD as classified by some studies): ~30–40%

- ADHD alone: ~25–35%

- Psychological / psychiatric conditions (depression, anxiety, etc.): ~25–30%

- Chronic health conditions (e.g., diabetes, migraine, autoimmune conditions): ~15–20%

- Mobility, sensory (vision/hearing), and other physical disabilities: ~10–15%

- Autism spectrum and other neurodevelopmental conditions: low single digits but probably under-reported

So, conservatively, about 1 in 15 to 1 in 10 medical students is officially “on the books” as disabled.

But when you ask about symptoms or functional impact without requiring formal registration, the numbers jump.

Many campus surveys show:

- 15–25% of medical students endorse significant, ongoing functional impairment from mental health or chronic conditions.

- Only a minority of that group has registered for accommodations.

Residents: the black box

For residency, the data are much worse. There is no universal equivalent of the AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire for residents.

Small to medium-size studies and survey work suggest:

- Self-identified disability among residents often runs around 6–15%, depending on how the question is asked.

- Formal documentation and accommodation use are markedly lower, often in the low single digits at a program level.

In plain English: there are disabled residents in virtually every program; very few are formally accommodated.

So How Many Actually Use Accommodations?

Registration is not the same as use. Some register for documentation reasons and rarely request changes. Others need robust, ongoing accommodations. Let’s split students vs residents.

Medical students: from disclosure to accommodation

National surveys of U.S. MD programs around 2016–2019 indicated:

- About 4.6% of medical students were registered with disability services.

- Roughly 3–4% actually used specific academic or clinical accommodations in a given term.

More recent snapshots show upward drift—schools reporting closer to 6–7% with documented disabilities and roughly 4–5% with active accommodations. Still far below the likely underlying prevalence.

Commonly reported patterns:

- Among students with a documented disability, 70–90% use at least one accommodation at some point during pre-clinical years.

- That usage drops modestly in clinical years, often because students fear stigma on the wards or believe accommodations “do not apply” in clerkships.

Residents: much lower formal use

Published resident data are sparse, but what exists lines up with what I hear off the record from program directors:

- 1–3% of residents in a given program typically have documented accommodations.

- The real prevalence of functional disability (physical, psychiatric, neurodivergent, chronic illness) is likely 10–20%.

So for every resident using a formal accommodation, there are probably 3–8 more in the same program silently adapting, suffering, or self-accommodating.

What Kinds of Accommodations Do Trainees Use?

The stereotype is extra time on tests. The reality is far more varied, especially in the clinical years.

Academic-phase accommodations (medical school)

Most common categories:

Testing-related

- Extended time (often 1.25x or 1.5x)

- Reduced-distraction or private room

- Breaks during long exams

- Computer-based instead of handwritten exams

Lecture and course access

- Audio recording of lectures

- Note-taking services or access to instructor notes

- Captioning or sign language interpreting

- Preferential seating, adaptive equipment for vision/hearing

Assignment and scheduling

- Flexible deadlines for written work

- Reduced course load with extended program duration (less common but critical for some)

For a learning disability or ADHD, you will see extended test time and quiet room in maybe 70–80% of cases. For psychiatric conditions, more scheduling flexibility and breaks. For sensory disabilities, technology and communication support dominate.

Clinical-phase accommodations (clerkships and residency)

Here the data are thinner but more revealing. Disability services offices and GME reports describe patterns like:

Schedule modifications

- No back-to-back 28-hour calls, or limits on consecutive night shifts

- Protected time for weekly therapy or medical treatments

- Adjusted clinic templates to reduce overbooking

Physical and environmental adjustments

- Adaptive equipment (ergonomic stools, assistive devices for procedures)

- Modified call rooms or on-call expectations when mobility is limited

- Accessible routes, parking, and workspaces

Cognitive / sensory accommodations

- Extra time for documentation or reading imaging

- Quiet workspace for note-writing

- Read-aloud software, screen magnification, color contrast optimization

- Written instead of purely verbal instructions for complex tasks

Leave and training length

- Intermittent medical leave integrated with the training schedule

- Extension of residency duration to accommodate significant health episodes

The striking point: most of these accommodations are relatively low-cost but high-yield if implemented properly. The barrier is not logistics. It is culture and fear.

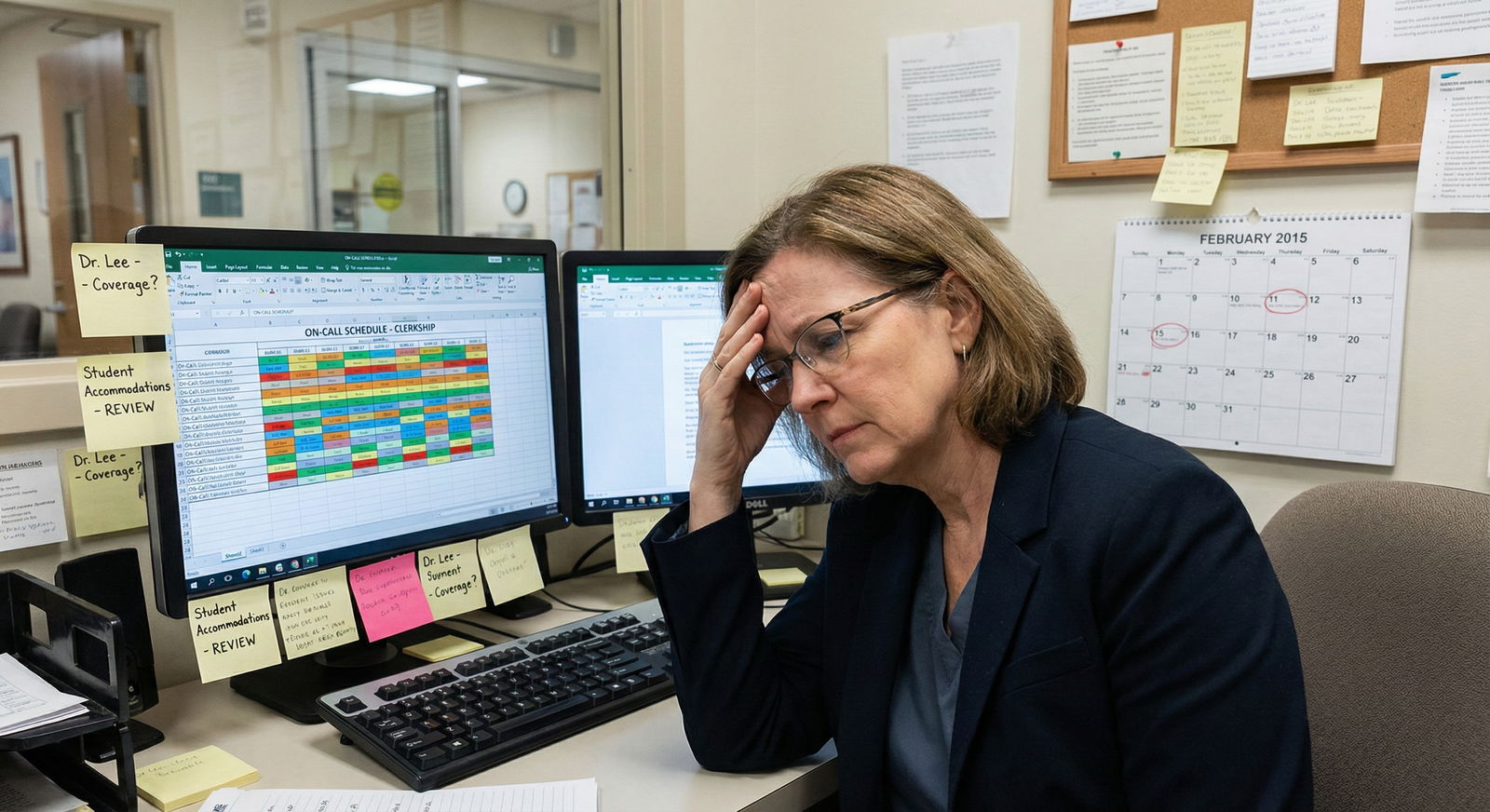

Where the Numbers Break: Underreporting and Barriers

If you compare expected disability prevalence to formal accommodation use, the gap is obvious.

Let’s do a rough-cut estimate for U.S. allopathic medical students:

- Total MD enrollment is roughly 95,000–100,000 students.

- If only 6% are documented as disabled, that is ~5,700–6,000 students.

- If actual functional disability is closer to 15%, we are missing another ~9,000 students.

So maybe one third of disabled students are formally registered; two thirds are quiet.

Residency? If there are about 150,000 residents nationwide and true disability prevalence is 15%:

- That is ~22,500 residents with significant functional impairment.

- If only 2–3% have formal accommodations, that is ~3,000–4,500.

- You are left with ~18,000 residents potentially “white-knuckling” it.

Not scientific to the last decimal, but directionally accurate.

Reasons are depressingly consistent:

- Fear of stigma and career damage

- Worry about being seen as less competent

- Lack of clarity about what is “allowed” under technical standards or ACGME requirements

- Prior negative experiences with accommodations in undergrad or MCAT testing

- Administrative friction: documentation, repeated forms, unclear processes

In resident focus groups, you hear the same line over and over: “I would rather suffer than risk being labeled.” That is the real driver of the data.

Comparing Across the Training Pipeline

To make this concrete, look at a simple pipeline from undergrad to practice.

| Stage | Self-Reported Disability* | Formal Accommodations |

|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate | ~20% | 10–15% |

| Medical School (MD) | 10–15% (estimated) | 4–7% |

| Residency | 10–20% (estimated) | 1–3% |

*Self-reported disability includes functional impairment even without formal registration.

The pattern is not subtle: as stakes increase and culture gets more hierarchical, formal accommodation use drops.

You can even think of it like a funnel:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | All trainees with significant impairment |

| Step 2 | Those who self identify as disabled |

| Step 3 | Those who disclose to institution |

| Step 4 | Those who request accommodations |

| Step 5 | Those who receive and use accommodations |

At each step, the count shrinks. Not because disability vanishes. Because risk perception spikes.

What the Data Say about Outcomes

This is where the conversation usually devolves into speculation. The data are actually more reassuring than most deans assume.

Academic performance and progression

Multiple studies in undergraduate and professional education show:

- When students with disabilities receive appropriate accommodations, their performance often approaches or matches that of nondisabled peers.

- Without accommodations, they have higher rates of exam failure, leaves of absence, and attrition.

In medicine specifically, small but rigorous studies have reported that:

- Students with ADHD or learning disabilities who receive exam and learning accommodations do not systematically underperform in course grades after support is in place.

- Failure or remediation often clusters before diagnosis or before accommodations are granted.

Residency data are weaker, but the pattern holds: carefully structured accommodations do not correlate with an explosion in remediation cases.

Wellness, burnout, and errors

There is a glaring absence of large-scale, linked data sets tying accommodation use to patient outcomes. But we do have decent signals:

- Residents with unaccommodated depression, anxiety, or sleep disorders show higher burnout scores and self-reported error rates.

- Accommodations that stabilize sleep, reduce random scheduling chaos, or enable consistent treatment are extremely likely to reduce risk, not increase it.

In plain terms: a resident with bipolar disorder who has predictable follow-up appointments and some guardrails around night shifts is a safer physician than one hiding everything and skipping meds.

Specialty and Program Differences

Programs are not equal. Some specialties, frankly, do better than others.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Psychiatry | 8 |

| Family Medicine | 7 |

| Internal Medicine | 6 |

| Pediatrics | 5 |

| General Surgery | 3 |

| Emergency Medicine | 2 |

Values here are an illustrative “accommodation visibility index” (0–10), drawing on published reports plus what I consistently hear from trainees and faculty.

- Psychiatry and family medicine tend to have more open cultures around mental health accommodations.

- Internal medicine sits in the middle; large academic centers vary widely by department leadership.

- Surgery and emergency medicine usually have the lowest visible accommodation rates, not because disabled people do not exist there, but because the cultural penalties for exposure are higher.

Program size matters too:

- Large academic programs are more likely to have formal disability policies, centralized GME processes, and legal counsel involved. That can help standardize accommodations.

- Small community programs may be more ad hoc: either surprisingly flexible (“We’ll just swap your calls”) or extremely rigid (“We cannot change the schedule; we have only four residents”).

There is no universal trend, but one rule holds: where leadership explicitly supports disability inclusion, the numbers of disclosed and accommodated trainees rise quickly over a few years.

Future Trends: Where the Numbers Are Likely Headed

Predicting exact percentages is foolish; directionality is not.

Trend 1: Upward slope in disclosure and accommodation

Factors pushing the curves upward:

- More trainees entering medicine with prior diagnoses and experience using accommodations in undergrad or on the MCAT.

- Legal pressure and clearer case law around disability in training and technical standards.

- Cultural shifts—slow, uneven, but real—around mental health and neurodiversity.

I would not be surprised to see documented disability in U.S. medical schools rise toward 10–12% over the next decade, with accommodation use somewhere in the 7–10% range. Residency will lag but follow.

| Category | Medical Students | Residents |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 5 | 2 |

| 2025 | 8 | 4 |

| 2030 | 11 | 7 |

Again, these are projections, but the direction matches both survey trends and institutional planning discussions.

Trend 2: Shift from test-based to workplace-based accommodations

As USMLE Step 1 moved to pass/fail and more schools relativize exam-based gating, the relative importance of pure testing accommodations will drop. Instead:

- Workplace design, scheduling flexibility, and assistive technologies will dominate the conversation.

- ACGME and specialty boards will push programs to define what counts as an “essential function” and what can be reasonably modified.

Expect more explicit policies about:

- Maximum shift lengths and mandatory rest periods.

- How to accommodate pregnancy, chronic illness, and disability in one integrated scheduling framework.

Trend 3: Data collection will get less terrible

Right now, tracking is episodic. Many institutions do not even know, at the dean’s office or GME level, how many trainees have accommodations.

You are going to see:

- Standardized disability questions in more national surveys.

- Better separation between “disability” and “temporary impairment” (e.g., post-surgery, pregnancy) in reporting.

- Stronger pressure from accrediting bodies for evidence that technical standards are being applied consistently and not as a blunt exclusion tool.

Expect more dashboards behind closed doors—deans reviewing trends in disability disclosure, accommodation usage, leaves of absence, remediation, and match outcomes together.

Practical Takeaways for Trainees and Institutions

If you are a trainee with disability-related needs:

- The data show you are not an outlier. You are in a statistically significant minority that grows every year.

- Formal accommodations are underused relative to need, especially in residency. That is a system failure, not proof you should “tough it out.”

- Outcomes tend to improve—not worsen—when accommodations are appropriately implemented.

If you are faculty or leadership:

- Assuming “we have no disabled trainees” is numerically absurd. You do. They are just not telling you.

- The most effective interventions are often simple: modest scheduling flexibility, assistive tech, clear policies, and a public stance that disability and high performance are not mutually exclusive.

- Tracking your own internal numbers (disclosure, accommodations granted, types used, outcomes) is the only way to move beyond anecdotes.

Where This Leaves the Future of Medicine

We are heading toward a workforce in which disability among physicians is not an exception story; it is part of the baseline distribution.

One more data-driven reality: the population is aging, chronic illness is more common, and medicine cannot afford a model that quietly ejects every trainee who does not fit a narrow physical and psychological template. It is mathematically unsustainable.

You will see more physicians with visible mobility aids, more with hearing devices, more openly autistic or ADHD clinicians, and more who manage serious mental health conditions while practicing safely. Quietly, in some places, this is already true.

And if institutions pay attention, you will also see:

- More systematic use of accommodations throughout training.

- Better retention of talented trainees who would otherwise burn out or be pushed out.

- A clinical workforce that better matches the diversity—visible and invisible—of the patients it serves.

Two or three numbers summarize the entire problem:

- Around 15–20% of people in education-age cohorts have a disability.

- Only about 4–7% of medical students and 1–3% of residents are formally accommodated.

- The gap between those lines is not hypothetical. It is lived experience, attrition, and avoidable harm.

Key Points

- The data show that disability among trainees is common, but formal use of accommodations is much lower than expected—especially in residency.

- When accommodations are actually used, they tend to be modest, practical changes that improve performance, safety, and retention rather than undermine standards.

- Over the next decade, you should expect rising disclosure rates, more workplace-focused accommodations, and a slow but real alignment between who has disabilities and who gets the support they need.