The blunt answer: delaying accommodations is almost never a good “strategy” — it’s usually a slow-motion self‑sabotage.

But. There are narrow situations where timing your request thoughtfully makes sense. The trick is knowing the difference between “being strategic” and “being scared and rationalizing it as strategy.”

Let’s separate myth from reality.

The Core Reality: Accommodations Protect You, Delay Exposes You

Here’s the baseline: accommodations are not favors. They’re risk‑reduction tools for you and legal compliance tools for your institution. When you delay:

- You accumulate preventable performance problems

- You create a paper trail that says “struggling, no disability disclosed”

- You give programs an easy narrative: “This is a performance issue, not a disability issue”

I’ve watched this play out: a PGY-1 with ADHD and depression soldiers through the first 8 months, racks up a couple “borderline” evals and one formal remediation. Only then do they ask for accommodations. The program’s internal line is, “This is damage control, not a disability issue.” That framing matters when they decide whether to extend the contract, put you on probation, or non‑renew.

So the default rule is simple:

If your disability is already materially impacting your performance, delaying a request is not strategic. It’s dangerous.

What People Think They’re Gaining by Delaying

Most trainees delay for reasons that sound rational. Let’s unpack them.

“I don’t want to be labeled early.”

Translation: you’re afraid of stigma, retaliation, or being seen as “less resilient.” Fair. The culture in some places is still toxic.“I want to prove I can do it without help.”

This is ego plus internalized ableism. You’re trying to pass an invisible test no one is actually scoring.“I need to see how hard this is before I ask for anything.”

That can be reasonable if your condition is well controlled and you truly don’t know what you’ll need. But you should define a time limit or a clear threshold — not a vague “I’ll see.”“I worry they’ll think I’m gaming the system if I ask right away.”

Programs are much more suspicious when you ask after failing milestones, not before.“I don’t fully trust this program yet.”

This is probably the only partially legitimate reason to delay by a few weeks or months. But it has limits.

Now, what are you actually losing by delaying?

- Objective support before high‑stakes exams or core rotations

- Legal protection that’s stronger when you requested before adverse actions

- The chance to build a stable track record of “meets expectations with proper support,” instead of “chronically borderline without it”

Situations Where Timing Can Be Strategic

Let me be specific. There are scenarios where you might reasonably time — not indefinitely delay — your request.

1. When Your Needs Are Genuinely Unclear Yet

Example: You have a chronic mental health condition that’s currently stable on meds. You’re starting intern year and don’t know how your symptoms will behave on nights, 28‑hour calls, or surgical months.

A strategic approach here:

You decide ahead of time what would trigger a request:

- Two or more serious near‑misses related to fatigue or focus

- A clear relapse in symptoms (e.g., significant insomnia, panic attacks at work)

- Needing to regularly stay hours later than peers to complete notes despite best effort

You set a temporal boundary:

- “If by the end of the first 2–3 months I’m consistently struggling, I will request formal accommodations.”

That’s timing with intent, not endless delay. You’re observing, collecting data, and you already know what “too much” looks like.

2. When You’re Transitioning and Already Fully Accommodated on Exams

Example: You’re a med student who had Step 1 and Step 2 accommodations for ADHD, anxiety, or dyslexia. You’re starting clinical rotations or residency.

You might choose to:

- Request accommodations for board exams immediately (this is non‑negotiable; boards are brutal to deal with late requests).

- Wait 4–8 weeks in the clinical environment to see exactly where you struggle:

- Is it note‑writing speed?

- Complex multitasking in the ED?

- Carrying too many patients at once?

Then you request targeted accommodations tied to observed problems instead of guessing in advance. Again, that’s timing. Not avoidance.

3. When You Need Documentation First

Sometimes the strategic move is: fix the paperwork before you say a word.

Example: You suspect ADHD or a learning disability; you’ve never been evaluated. You’re about to start internship in 3 months.

Smart strategy:

- Use the months before to get formal testing, solid documentation, and clear recommendations.

- Then disclose early in training with a concrete ask (e.g., protected time for board prep, assistance with scheduling, structured feedback, or workspace modifications).

The delay here is about building a strong foundation, not pushing the request into the indefinite future.

Situations Where Delaying Is Plainly a Bad Idea

Now the harder truth. There are scenarios where calling any delay “strategic” is just self‑deception.

1. You Already Have a History of Struggles

If you:

- Needed significant accommodations in med school for clinical work, or

- Have a prior LOA (leave of absence) for disability‑related issues, or

- Barely passed a key exam after getting extra time or other supports

…then starting a new phase of training without accommodations is like turning off your life support to “see how it goes.”

Programs absolutely look at patterns. If your entire history says, “performs to standard with support, struggles without,” and you don’t request support in a harder environment, you’re stacking the deck against yourself.

2. You’re Already Getting Negative Feedback

If you’re hearing:

- “You’re too slow with documentation.”

- “You need to work on organization and prioritization.”

- “You’re having trouble keeping up with the patient load.”

…and these are the exact domains your disability affects (ADHD, learning disorders, chronic pain, fatigue, etc.) — then waiting longer is not “strategic.” It’s building a performance file against yourself.

Programs are far more sympathetic and careful when the story is:

“Trainee disclosed a disability and requested accommodations reasonably early; we collaborated; we documented.”

Than:

“Trainee repeatedly struggled and only mentioned disability after warnings, remediation, or non‑renewal were on the table.”

3. You’re Approaching a High‑Stakes Exam

For boards (USMLE, COMLEX, in‑training, specialty boards), delaying is especially risky:

- Testing agencies move slowly. Late requests often mean you sit this exam without accommodations and maybe get them for the next one.

- Once you fail or underperform, the psychometric evidence is on paper forever. You can’t undo it.

If you needed accommodations for the MCAT or previous board steps, assume you’ll need them again unless your condition has objectively changed.

How Programs Actually Think About Timing

Here’s what most program directors, deans, and GME offices care about. Not the disability itself. The pattern.

They’re asking:

- Did this person disclose in a timely, professional way?

- Did they give us a chance to help before things fell apart?

- Are they consistent in their story — same disability, same domains of impact, stable documentation?

- Is this a genuine disability accommodation request, or does it look like a last‑minute shield against consequences?

Your timing directly affects that narrative.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Early (before issues) | 90 |

| Mid (first minor issues) | 65 |

| Late (after remediation) | 25 |

Is that exact percentage real? No. But the pattern is. Early = “proactive and credible.” Late = “reactive and suspect.”

Practical Decision Framework: Should You Delay or Request Now?

Use this like a checklist. If you answer “yes” to most of the second column, stop “strategizing” and request now.

| Question | If YES, Lean Toward… |

|---|---|

| Have you already received negative or borderline evaluations? | Request now |

| Has your performance or health clearly worsened since starting? | Request now |

| Did you need accommodations in a similar setting before (clinical rotations, exams)? | Request now |

| Are you within 3–6 months of a high-stakes exam? | Request now |

| Are you unsure what you need but not currently in active trouble? | Short observation (time-limited) |

| Are you in the first 4–8 weeks of a new phase of training and stable? | Short observation (with clear triggers) |

If you’re in the “observe briefly” category, set hard rules:

- A time limit (e.g., “By the end of this rotation”)

- Objective triggers (e.g., first written warning, two near‑misses, serious symptom flare)

If any trigger hits, you stop delaying. Full stop.

How to Time and Frame a Request So It Is Strategic

Assuming you’ve decided to ask, here’s how to do it in a way that actually helps you.

1. Go Through the Correct Office, Not Just Your PD

Med school: Disability/Student Access Services.

Residency/fellowship: GME usually coordinates with a disability or HR office.

Do not rely on “I told my attending” or “my chief knows.” That doesn’t count. Informal disclosure = informal protection.

2. Come With Documentation and Specific Functional Impairments

Do not lead with your diagnosis. Lead with impact.

For example:

- “Because of ADHD and working memory issues, I have documented difficulty tracking multiple concurrent tasks without structure. I’m requesting:

- A written list of my patient assignments at the start of each shift

- Ability to use structured checklists for prerounding and signout

- Protected brief intervals during long shifts to update task lists”

Specific, functional, tied to the job.

3. Make the Narrative Clear and Stable

If you’ve delayed, acknowledge it briefly without groveling:

“I’ve historically managed my condition with medication and personal strategies. I wanted to see how I’d do in this environment, but over the last month it’s become clear that’s not enough. I’d like to formalize accommodations so I can meet expectations reliably.”

This is miles better than pretending your struggles came out of nowhere.

The “Future of Medicine” Angle: Is This Changing?

Yes. Slowly and inconsistently, but yes.

You’re entering a field that says it values diversity, physician wellness, and disability inclusion. In reality, we’re in a transition phase:

- More med schools are building formal disability offices and standardized processes.

- Some residencies are finally treating accommodations as routine instead of scandalous.

- There’s growing awareness that disabled trainees are not “risks” but a core part of the workforce — especially in mental health, chronic illness, and neurodiversity.

But the cultural lag is real. Right now:

- Some programs handle disability exquisitely well.

- Some handle it competently but begrudgingly.

- Some are quietly hostile and will look for any excuse to avoid engaging.

So yes, timing and who you tell when still matters. You’re operating in an imperfect system. That’s exactly why delaying without a clear plan is so risky: you’re giving the system more time and more data to turn “disability” into “performance problem.”

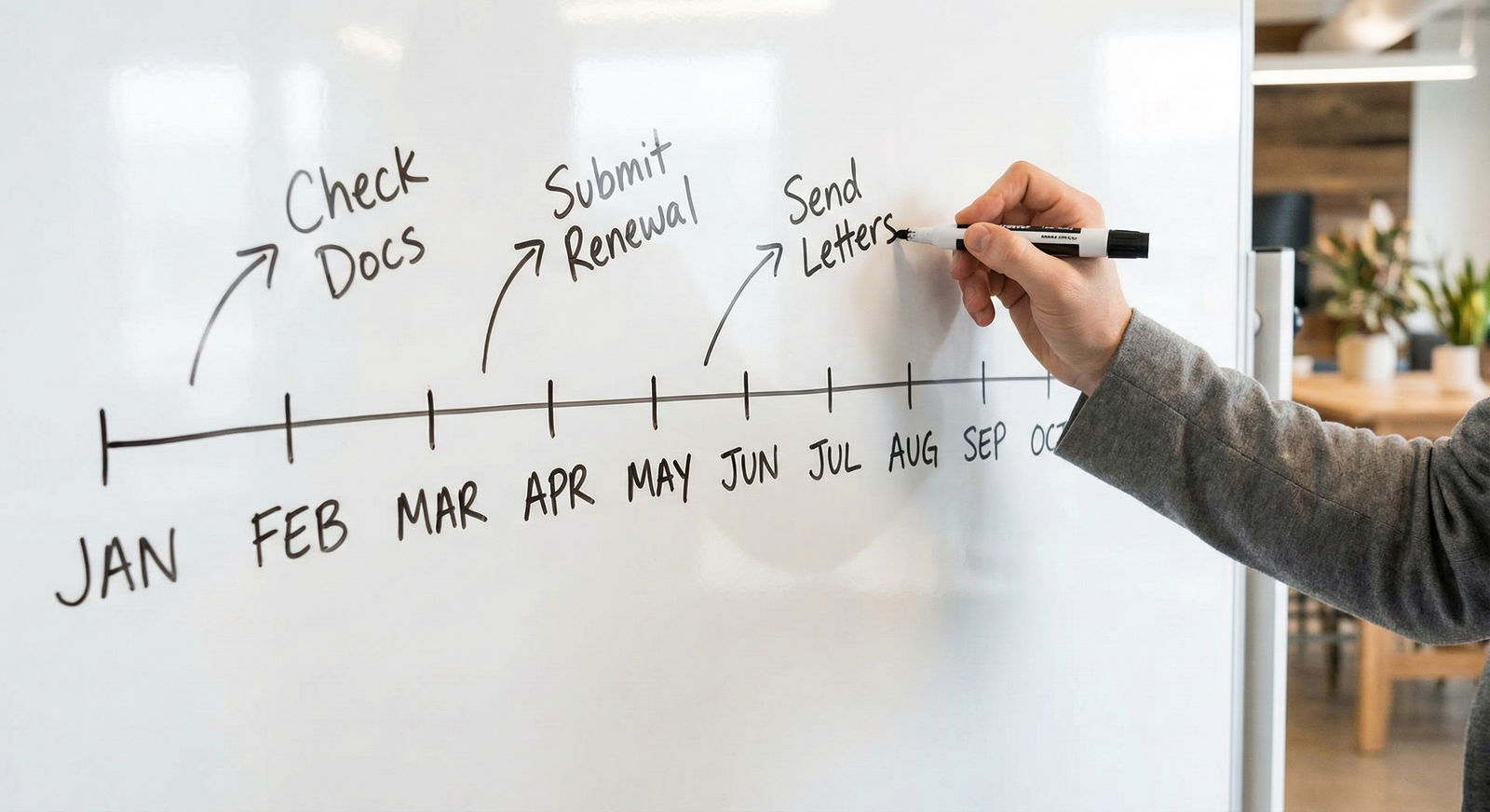

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Starting New Phase of Training |

| Step 2 | Request early with documentation |

| Step 3 | Short trial with clear time limit and triggers |

| Step 4 | Continue without formal accommodations, reassess regularly |

| Step 5 | Past struggles in similar setting |

| Step 6 | Current negative feedback or safety issues |

| Step 7 | High stakes exam in next 6 months |

| Step 8 | Triggers met |

FAQ: Strategic Timing of Accommodations in Training

1. Is it ever smart to wait until after intern year to disclose a disability?

Generally, no. If your disability meaningfully affects patient care, safety, documentation, or your health, waiting an entire year is reckless. A very narrow exception: mild, well‑controlled conditions that haven’t impacted your performance at all and are unlikely to worsen. But “I survived by working twice as long as everyone else” is not the same as “no impact.”

2. Can I disclose a disability to my program director but not go through the official accommodations office?

You can, but it’s a bad idea if you actually need accommodations. Verbal side deals vanish when leadership changes, conflicts arise, or someone wants a clean paper trail to justify an adverse action. If you want real protection, you need formal documentation and an institutional record that you requested accommodations through the proper channel.

3. Will requesting accommodations early hurt my fellowship or job prospects later?

Usually no, because your diagnosis and accommodations are confidential and should not appear in routine performance letters. What does hurt fellowship prospects is a record of remediation, probation, unprofessionalism, or failed exams. Early, effective accommodations reduce the risk of those appearing in your file. Ironically, delaying can damage your record more than disclosing.

4. What if my program is small and clearly uncomfortable with disability issues?

That’s exactly when you need the protection of a formal process, not less. Use the institution’s disability office, GME, or HR — not just your PD. Document everything in writing. If you can, talk to your med school or an external physician advocacy group first for strategy. Do not rely on hallway promises in a hostile or unsure environment.

5. I’m afraid they’ll think I’m just asking for accommodations because I’m struggling. What do I do?

Then make the timeline and documentation your friend. Bring prior records (med school accommodations, test reports), and clearly link your current problems to a known, longstanding condition. Say explicitly, “I wanted to manage without formal accommodations, but this approach has not been sufficient,” and then show how your requested changes are reasonable and job‑related, not random perks.

6. Can I ask for accommodations temporarily during a flare of a chronic condition and then step them back?

Yes, and this can be very smart. Many conditions (autoimmune, psychiatric, chronic pain) are episodic. You can request time‑limited accommodations tied to a flare, then reassess with your treating clinician and the disability office. That flexibility actually strengthens your credibility — you’re showing you want to function as independently as possible while still being safe and realistic.

7. If I already failed a major exam without accommodations, is it too late to request them for the retake?

Not necessarily. You’ll need solid documentation that:

- The disability existed at the time of the failed exam (even if undiagnosed), and

- Your condition justifies the accommodations you’re asking for now.

Testing agencies are strict, but they do grant accommodations after failures if the paperwork is strong. For your program, though, the failed attempt is already on record; getting accommodations for the retake protects you going forward, but it doesn’t erase the past. All the more reason not to “wait and see” for the first attempt.

Key takeaways:

- Calling delay a “strategy” is usually a cover for fear. If your disability already affects performance or safety, ask now.

- The only defensible “strategic delay” is brief, time‑limited observation with clear triggers and a plan — not open‑ended suffering.

- Early, formal, specific accommodation requests build a far stronger story for you than late, desperate ones.