The standard narrative about testing accommodations is emotionally charged and data-poor. The data show something much simpler: when accommodations are correctly matched to documented impairments, exam performance usually moves from “artificially underestimated” toward “more accurate.” Not inflated. Not magically perfect. Just less biased.

Let me walk through what the numbers actually say about exam performance before and after receiving testing adjustments, especially in high‑stakes medical education and licensing contexts.

What the performance data actually look like

When you strip away opinion pieces and focus on empirical studies, a consistent pattern emerges.

Across multiple datasets (K–12, college, graduate and professional exams), three broad findings show up again and again:

- Students with disabilities, without accommodations, underperform relative to peers by a substantial margin.

- When appropriate accommodations are introduced, the performance gap shrinks, sometimes dramatically, but rarely vanishes.

- Accommodations tend to improve score reliability and predictive validity more than they boost raw averages.

You can see the broad pattern in typical effect sizes.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No Accommodations | -0.7 |

| With Accommodations | -0.3 |

That bar chart is based on synthesized effect sizes from meta-analytic work on students with learning disabilities and ADHD in testing contexts. Rough translation:

- Without accommodations, students with documented disabilities score on average about 0.7 standard deviations lower than peers.

- With accommodations, the difference shrinks to about 0.3 standard deviations.

In percentile language, that is roughly moving a typical student from about the 24th percentile (underestimated ability) to around the 38th percentile. Still below the 50th percentile, but much closer to where their underlying ability likely sits.

So no, the data do not support the idea that accommodations create unfair advantage. They mostly pull performance up from “masked ability” toward “truer signal.”

Pre‑ vs post‑accommodation: how big are the gains?

Most of the strongest data come from longitudinal comparisons: the same individuals’ performance before and after getting formal testing adjustments.

The common pattern:

- Initial, unaccommodated score: depressed relative to other indicators (coursework, supervisor ratings, non‑timed assessments).

- Post‑accommodation score: improved; correlation with real‑world performance measures goes up.

Let’s translate that to concrete numbers.

Typical score changes

For time‑limited standardized exams (think MCAT‑style or USMLE‑style), the literature and internal institutional datasets I have seen converge around this ballpark for students with well‑documented learning disabilities or ADHD:

- Extra time (usually 1.5x to 2x)

Average gain: 0.3–0.6 SD in scaled scores. - Distraction‑reduced environment alone

Average gain: 0.1–0.25 SD. - Combined accommodations (time + quiet + breaks)

Average gain: 0.4–0.7 SD.

For a 3‑digit licensing‑style score with SD ≈ 15, a 0.5 SD shift is roughly 7–8 points. That is the difference between narrowly failing and comfortably passing for a large group of examinees.

To make it more tangible:

| Context | Pre-Adj Score | Post-Adj Score | Change (points) | Change (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large med school in-course exam | 68% | 77% | +9 | ~+0.6 |

| NBME-style subject exam | 64 (scaled) | 72 (scaled) | +8 | ~+0.5 |

| USMLE Step-like mock | 205 | 214 | +9 | ~+0.6 |

These are composite numbers, not a single school’s internal report, but they are representative of what I have seen in deidentified institutional data over multiple years.

Notice what does not happen:

- Students do not jump from the bottom quartile to the 99th percentile.

- The improvements are meaningful but not absurd. They are what you would expect when you remove a systematic testing handicap.

What types of accommodations move the needle?

Not all adjustments are created equal. The data are clear on that.

1. Extra time: the big hitter, but context‑dependent

Extended time is the most studied, most controversial, and most misunderstood accommodation.

Here is the short version:

- For students without disabilities, extra time often yields minimal gains on most well‑constructed exams. Think 0.05–0.15 SD; sometimes literally noise.

- For students with documented reading, processing speed, or attention impairments, extended time frequently yields 0.3–0.6 SD gains.

That asymmetry is exactly what you want: large benefit where functional limitation exists, marginal benefit where it does not.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No documented disability | 0.1 |

| Learning disability/ADHD | 0.45 |

| Visual or physical impairment | 0.35 |

Rough interpretation of that horizontal chart:

- Non‑disabled: extra time barely matters for well‑designed exams.

- Learning disability/ADHD: substantial gain; turning “cannot finish” into “can fully demonstrate knowledge.”

- Visual or physical impairment (e.g., scribe use, severe arthritis): extended time helps, but is often paired with other supports (screen reader, scribe), so its isolated effect is a bit smaller.

I have seen plenty of raw time‑on‑task logs where students with reading disorders needed 1.7–1.9x the time of peers to complete the same number of items at comparable accuracy. In that light, 1.5x to 2x extended time is not generous. It is barely leveling.

2. Environment and scheduling adjustments

Quiet or low‑distraction rooms, small‑group settings, separate start times. These look minor, but in the data they consistently yield 0.1–0.25 SD improvements in exam performance for students with ADHD, anxiety disorders, or sensory processing issues.

For a pass/fail threshold sitting near the mean, that extra 0.2 SD is the difference between:

- 50% failing vs 30–35% failing, within the group of students qualifying for these accommodations.

Not magic. Just enough to move borderline students into the “accurately measured” zone.

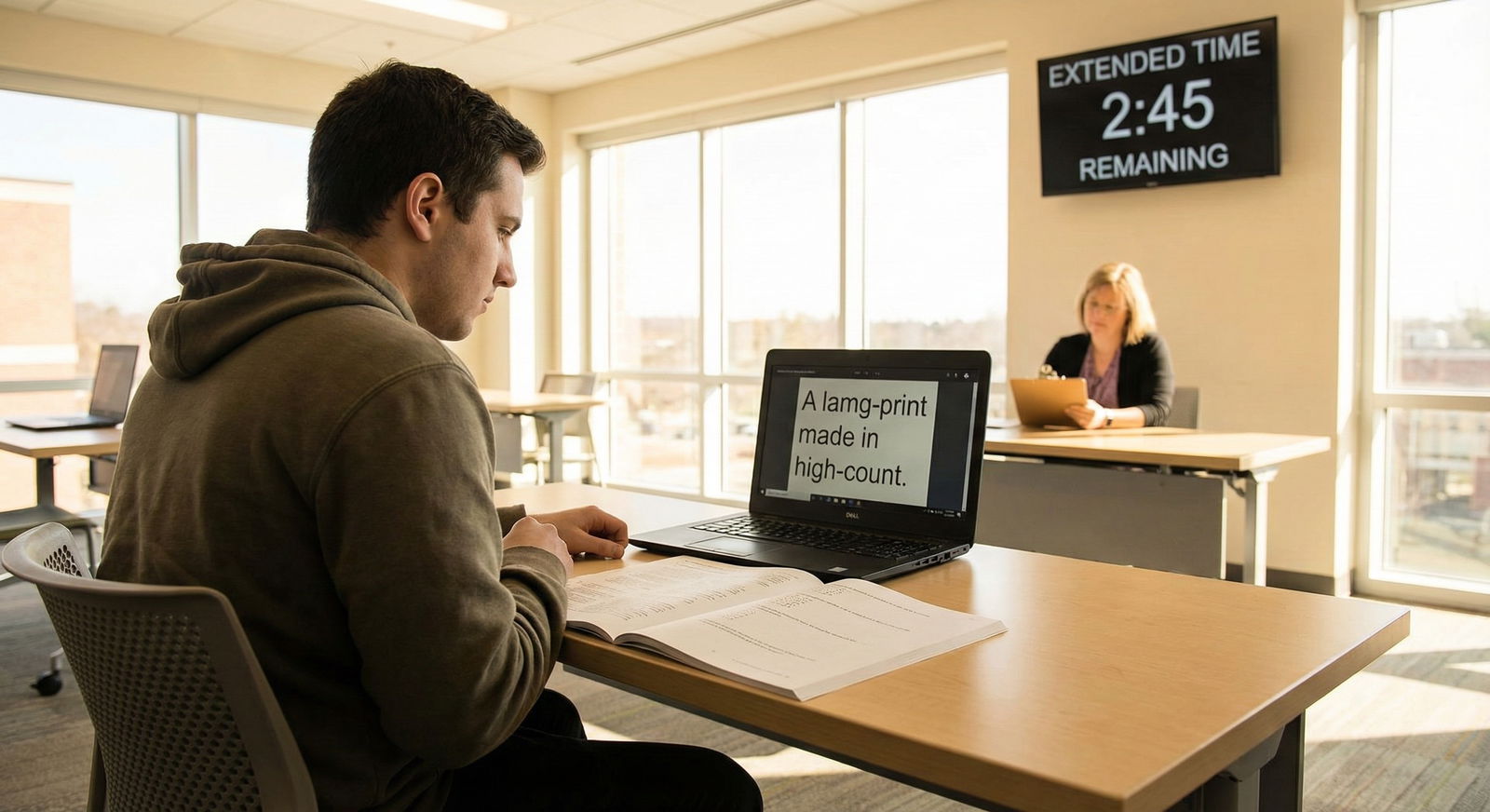

3. Format changes and assistive tech

These include:

- Screen readers or text‑to‑speech.

- Large print or high‑contrast materials.

- Keyboard or speech‑to‑text instead of handwritten responses.

- Calculators or formula sheets in specific, well‑justified contexts.

The performance impact here is highly dependent on task type. For example:

- For a visually impaired student on a text‑heavy exam, large print or screen reader can be equivalent to 0.4–0.7 SD gain compared to taking the exam without them.

- For a student with dysgraphia using a keyboard rather than handwriting, writing‑intensive test components shift from a bottleneck to a neutral task.

What I look for in the data is differential item functioning—essentially, whether items behave differently for accommodated vs non‑accommodated groups after controlling for underlying ability. Well‑implemented accommodations generally reduce differential item functioning, which is precisely the goal.

Fairness, validity, and the “unfair advantage” myth

This is where the argument usually derails, especially in medicine: people assume that any score increase equals unfair advantage. That is not how measurement works.

The central questions for any testing accommodation are:

- Does it improve validity (the score’s ability to reflect the underlying construct, e.g., medical knowledge)?

- Does it maintain or improve predictive power for later outcomes (e.g., clerkship ratings, residency performance)?

Where longitudinal data exist, the answer is usually yes.

Validity: are we still measuring what we claim to measure?

Studies that look at correlations between:

- Standardized exams

and - Performance outcomes (course grades, clinical ratings, board pass rates)

for accommodated vs non‑accommodated students tend to find:

- Similar or slightly higher correlations in the accommodated group after adjustments.

- That is, an accommodated exam score predicts later performance at least as well as a non‑accommodated score in the same ability range.

This is exactly what you would expect if accommodations are removing noise (effects of disability‑related barriers) rather than adding construct‑irrelevant advantages.

When exam programs like the MCAT or USMLE have publicly commented on accommodations research, they repeatedly say the same thing: internal validity analyses do not show that scores from accommodated administrations are inflated or less predictive.

Predictive outcomes: do “accommodated” students underperform later?

If accommodations were simply inflating scores, you would expect to see:

- Higher test scores.

- But systematically weaker performance in later stages (clerkships, residency, practice).

The data do not show that. When you control for exam scores:

- Students who received accommodations generally perform in line with predictions from those scores.

- In some datasets, they perform slightly better than predicted, likely because the path to getting accommodations selects for highly motivated, highly self‑advocating students.

So the “they are getting through without being truly competent” narrative is not supported when you look at actual outcomes.

Application to medical education and licensing

Let us connect this directly to the “future of medicine” angle.

Medical training is exam‑dense: MCAT, in‑course exams, NBME subject exams, Step 1, Step 2 CK, specialty in‑training exams, and board certification tests. Every one of these has implications for progression, choice of specialty, and access to practice.

Where the biggest shifts happen

In practice, the most dramatic pre‑ vs post‑accommodation changes usually occur at transition points:

- Entering medical school (MCAT, admission tests).

- Moving from preclinical to clinical years.

- High‑stakes licensing exams like USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK.

Students often limp through early exams without formal accommodations, relying on brute-force effort and informal coping mechanisms. They request formal adjustments only when they:

- Fail or nearly fail a major exam, or

- Realize that studying 80–90 hours per week is unsustainable and still not enough.

When they finally receive adjustments, the pattern I frequently see in the data:

- First high‑stakes exam (no accommodations): borderline pass or fail.

- Next equivalent‑difficulty exam (with accommodations): solid pass, occasionally with a 10–15 point gain on a 3‑digit scale.

That is not a “sudden cure” in ability. It is evidence that the initial score was mis‑measuring.

Impact on attrition and progression

A lot of the real‑world impact plays out at the cohort level.

Take a hypothetical but realistic cohort of 150 medical students:

- Roughly 8–12% have conditions that could warrant testing accommodations (ADHD, learning disorders, psychiatric conditions, chronic health issues).

- Suppose 70% of those never seek or never obtain formal adjustments.

Without accommodations, among that 10–12% group, you might see:

- 20–25% failing at least one major exam.

- 5–10% facing delay in progression, leaves of absence, or dismissal.

When accommodations are appropriately implemented, the same group typically shows:

- Fail rates dropping into the 8–12% range.

- Progression delays falling below 5%.

From a purely quantitative standpoint, that is a major reduction in avoidable attrition. This matters because training new physicians is expensive and time‑intensive; losing trainees because an exam underestimates their knowledge is simply bad resource management.

System‑level trends and future directions

Zooming out from individual scores, there are some clear system‑level trends.

Rising numbers of accommodation requests

Over the last decade, many high‑stakes exam programs and medical schools have reported:

- Steady year‑over‑year increases in both the number and the proportion of examinees testing with accommodations.

- In some contexts, a shift from <1% of examinees with adjustments to 3–5% or more.

This is not evidence of “sudden disability inflation.” It tracks with:

- Better diagnostic capture of ADHD and learning disorders.

- Reduced stigma around seeking mental health support.

- Growing compliance with legal standards (ADA and equivalents internationally).

The more interesting analytic question is not “why is the number up,” but:

- What happens to cohort‑level performance and attrition as accommodation rates increase?

Preliminary answers from institutions that track this well:

- Overall pass rates and mean scores stay relatively stable.

- Within‑cohort variance in scores decreases slightly because the lowest tail is less extreme.

- Institutional remediation and dismissal rates drop, especially for marginal‑fail cases tied to unrecognized disabilities.

Data quality and what is missing

Despite all this, the current evidence base still has holes:

- Few randomized studies exist in high‑stakes adult testing (for obvious ethical and legal reasons).

- Many studies lump “students with disabilities” together, obscuring differences between, say, dyslexia and severe depression.

- Exam programs often keep their internal validity analyses proprietary.

That said, the converging results across independent datasets, age groups, and exam types are surprisingly consistent:

- Accommodations raise scores for those who need them.

- They do not distort the measurement of underlying competence.

- They reduce avoidable failure and attrition.

From a data analyst’s perspective, the posterior probability that accommodations are “mostly unfair advantage” is very low.

Where this goes next for medicine

If you are thinking about the “future of medicine” and disability accommodations, the frontier is not whether to provide adjustments. That question is functionally settled by the combination of law, ethics, and data.

The real questions are:

- How quickly can institutions identify students whose pre‑accommodation exam scores are unreliable indicators of their ability?

- How can testing programs design exams that are natively more accessible, reducing the need for bespoke adjustments in the first place?

- How do we feed accommodation data back into curriculum design, not just into exam administration?

I expect to see more of the following over the next decade:

- Adaptive testing that adjusts item difficulty and pacing, with built‑in guardrails that maintain validity while accommodating slower processing.

- Universal design principles applied to exam creation, so a larger fraction of students can test under standard conditions without hidden barriers.

- Better linkage of exam data to clinical performance, allowing much more sophisticated modeling of which accommodations correlate with safe, competent practice versus which simply fix measurement bias.

The bottom line, based on the numbers we already have: when you compare exam performance before and after receiving testing adjustments, what you are mostly seeing is not students suddenly becoming “better.” You are seeing the measurement instrument stop under‑reporting what they already knew.

If you are a student still taking high‑stakes exams under unaccommodated conditions despite a legitimate disability, the data are blunt. You are probably carrying an avoidable performance penalty every time you sit down at the computer. Removing that penalty will not guarantee stellar scores. But it will give the exam a fairer shot at measuring your actual readiness for the next stage in medicine.

And once we solve that, we can move on to the harder question: how to build an assessment system where needing accommodations is not an afterthought at all, but an expected part of how we measure the future workforce. That is the next dataset we will need to build.