The biggest myth about disability accommodations is that it’s about “whether you qualify.” It isn’t. Inside committees, the real question is: did you give us enough ammunition on paper to justify saying yes without getting burned later?

That’s the game. And most students don’t even know they’re playing it.

I’ve sat in those rooms. I’ve watched otherwise solid requests get denied because the documentation was vague, outdated, or politically risky for the committee to bless. Not because the disability wasn’t real. Because the paperwork wasn’t strategically built for the way these people actually think.

Let me walk you through how the decision really gets made.

What Committees Are Actually Afraid Of

They won’t say this out loud, but the committee is not primarily thinking, “How do we help this student the most?” Their internal soundtrack is more like:

- “Can we defend this if someone challenges it?”

- “Does this create precedent we can’t sustain?”

- “Are we violating professional/technical standards if we approve this?”

- “Does this look like we’re just giving extra time to anyone who asks?”

Behind closed doors, you’ll hear phrases like:

- “I don’t see objective evidence here.”

- “This reads like coaching.”

- “This would fundamentally alter the assessment.”

- “We’re exposing ourselves if we grant this with what’s in this file.”

So when they read your documentation, they’re not just seeing your history; they’re seeing risk. Legal risk, accreditation risk, fairness complaints from other students, blowback from faculty, and in high-stakes exams, scrutiny from testing agencies and boards.

You want to know if your documentation is “enough”? Translate that into: Is this documentation strong enough that approving this request is the least risky option for the committee?

If yes, you win. If no, you get “insufficient evidence” or the classic, “We are unable to support this level of accommodation at this time.”

The Four Filters Every Committee Uses (Whether They Admit It or Not)

They don’t always spell it out, but almost every committee is running your documentation through four filters: diagnosis, impairment, functional impact, and nexus to the specific accommodation. If you’re weak in any one of these, you’re vulnerable.

1. Diagnosis: “Is this a real, current, defensible condition?”

They are not just asking, “Do we believe you?” They’re asking, “Can we defend this diagnosis as credible and current if an auditor or regulator looked at it?”

What they quietly check:

Is the diagnosis made by the right type of professional?

- ADHD from a coach or primary care note with three lines? Weak.

- ADHD from a full psychoeducational eval with testing? Strong.

- “Anxiety” from a campus counselor with a short letter? Meh.

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder / PTSD / Major Depressive Disorder from a treating psychologist/psychiatrist with detailed history? Much stronger.

Is it current enough for the context?

- For K–12 and some colleges, 3–5 years can be fine.

- For boards (USMLE, NBME, MCAT accommodations, specialty boards), they silently prefer within 1–3 years for many conditions, especially ADHD and learning disorders.

- “Diagnosed in 7th grade, no recent data” is an automatic side-eye on most committees.

Does the documentation show actual clinical rigor?

- Name of tests used (e.g., WAIS-IV, Woodcock-Johnson, TOVA).

- Multiple data sources (history, interviews, rating scales, test scores).

- Clear diagnostic criteria referenced (DSM-5, ICD-10/11).

- Not just “student reports difficulty concentrating.”

2. Impairment: “How bad is it, on paper?”

This is where a ton of students get sunk. They have a real condition, they struggle, but their documentation makes it sound mild or intermittent.

Committees are looking for evidence of substantial limitation compared to peers. Not just “this is hard,” but “this is significantly harder for this person than for a typical student in similar circumstances.”

They look for:

Standard scores and percentiles that show clear deficits

- Processing speed, working memory, reading fluency, sustained attention.

- Borderline or low-average scores that are clearly out of line with their overall cognitive ability.

Pattern of historical impairment

- Old IEP/504 plans (with details, not just checkboxes).

- Prior accommodations used and documented.

- Report cards or narrative comments describing difficulty.

Concrete examples in clinician letters

- “He requires 3–4 hours to complete reading tasks that typically take 1 hour.”

- “Processing speed is in the 5th percentile despite high-average reasoning ability.”

- “In timed settings, accuracy drops by over 30% when compared to untimed performance.”

When the file only says, “The student experiences difficulty focusing during exams,” insiders read that as: no objective impairment documented.

3. Functional Impact: “So what actually happens when they don’t have accommodations?”

The diagnosis can be solid. The impairment scores can be decent. But if the evaluator or clinician never explicitly links that to what happens in actual coursework or testing, committees will call it “not enough.”

What they’re hunting for:

Specific academic scenarios:

- “Cannot finish board-style questions within standard time without leaving 15–20 unanswered.”

- “Written exam performance is significantly lower than observable knowledge in oral/clinical formats.”

- “Reading heavy stems and multi-step questions leads to errors despite understanding content in discussion.”

Real-world clinical or lab impact:

- “In fast-paced clinical documentation, patient notes are often incomplete unless given protected time.”

- “In OSCE scenarios requiring rapid shifts of attention, the student misses key steps unless provided structured prompts or extra planning time.”

Measurable fallout:

- Failed or borderline scores in timed standardized assessments vs stronger performance in non-timed or lower-stakes settings.

- Consistent pattern: reads slow, tests poorly in timed formats, but knows the material.

What weak documentation does: “Student is stressed during tests and worries about performance.” No numbers. No concrete consequence. That’s an easy deny.

4. Nexus: “Why this accommodation, not just any support?”

This is the one students almost never understand and clinicians only sometimes get right: you’re not just proving you have a disability; you’re proving that the specific accommodation requested is a logical, necessary response to that disability.

If you’re asking for 50% extra time, the file needs to say, in substance:

“Because of X documented impairment, extra time compensates for Y deficit, and there’s evidence it helps this student perform on par with nondisabled peers.”

That means:

Extra time requests tied to:

- Slow reading fluency, low processing speed, impaired working memory.

- Not just “test anxiety.” They roll their eyes at that alone.

Separate room requests tied to:

- Documented distractibility, sensory sensitivity, PTSD triggers, severe anxiety with observable physical manifestations, tics, etc.

Breaks / stop-the-clock tied to:

- Medical conditions (diabetes, POTS, Crohn’s, migraines).

- Need for restroom access, blood glucose checks, physical stretching.

- Or cognitive conditions where mental stamina is impaired in documented ways.

When the letter says, “I recommend extra time as the student would benefit from it,” that’s a red flag phrase. Almost everyone “benefits” from extra time. You have to show necessity, not convenience.

How Boards and High-Stakes Exams Quietly Raise the Bar

Everything gets harsher the moment you touch national exams: MCAT, USMLE, COMLEX, specialty boards, in‑training exams. The culture shifts from “educational assistance” to “legal and psychometric scrutiny.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Campus exams | 20 |

| Medical school finals | 40 |

| NBME subject exams | 65 |

| USMLE/COMLEX | 85 |

| Specialty boards | 95 |

Those numbers are conceptual, but the gradient is real. Here’s what changes behind closed doors:

They care more about longitudinal history.

- If your first documented diagnosis appears at age 26 when you apply for Step 1 accommodations, they are immediately skeptical.

- They want a story that starts earlier: K–12, SAT/ACT, college, med school.

They dissect “previous success without accommodations.” You’ll hear committee members say:

- “They got through undergrad at a top school without accommodations. Why now?”

- “MCAT was taken standard time. That undermines the argument for Step 1 extra time.”

This is one of the ugliest secrets: prior success is often held against you. Unless your documentation explicitly explains why.

They demand tight internal consistency.

- If your neuropsych eval shows average processing speed but you’re asking for 100% extra time, they’ll push back.

- If narratives from different clinicians conflict (one says mild, one says severe), they will default to the milder reading.

They are conservative about “fundamental alteration.” That phrase—fundamental alteration—is their shield. If they believe an accommodation changes what the exam is measuring (e.g., giving a calculator on a mental math exam; unlimited time on an exam where speed is an essential construct), they deny and feel legally safe doing so.

So when you’re heading toward boards, “good enough” documentation from undergrad becomes “absolutely not enough” in that context.

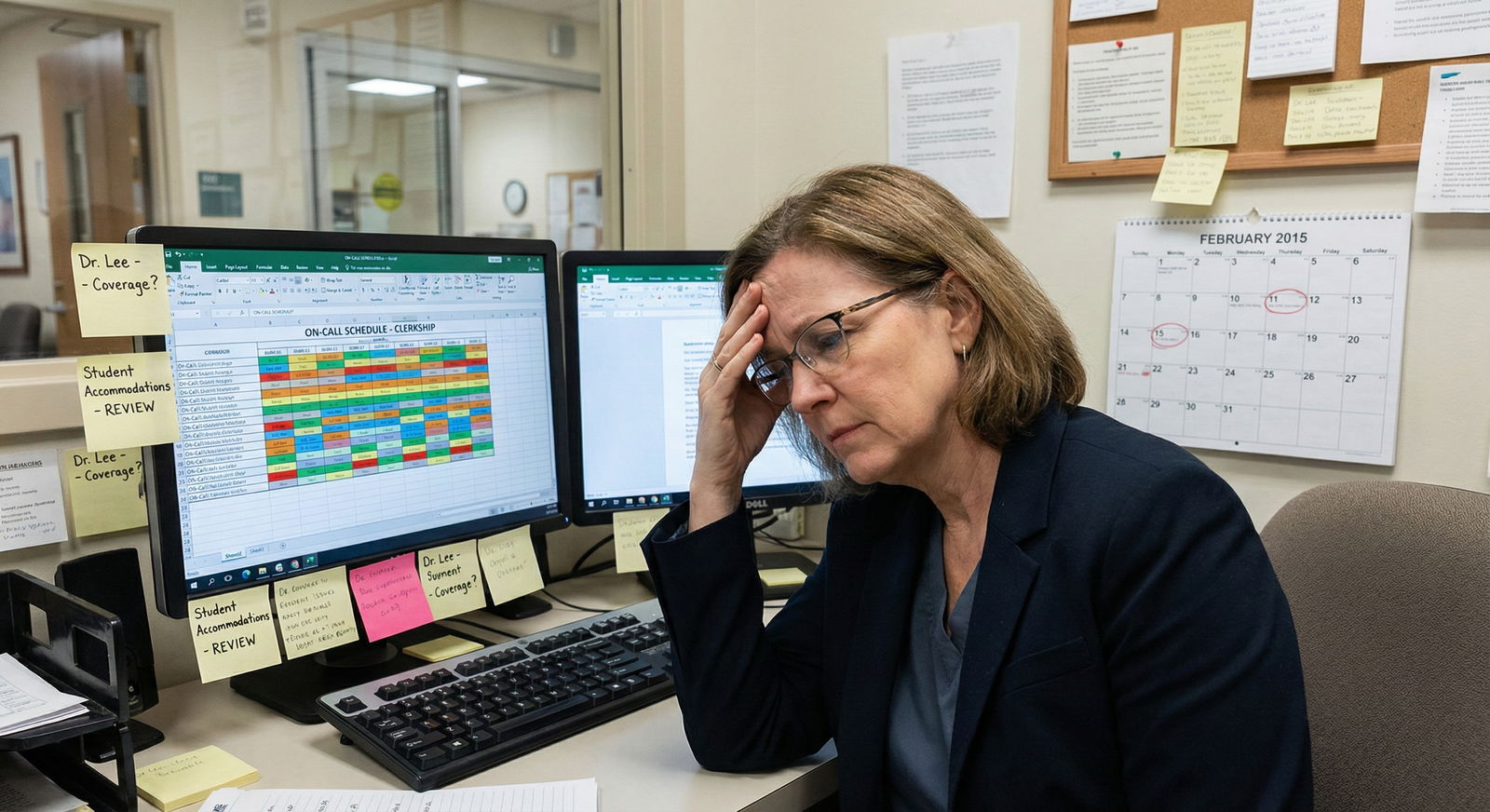

The Political Layer No One Tells You About

Let me be blunt: identical documentation does not always get identical decisions. Context and politics creep in.

1. Volume and fatigue

I’ve seen meetings where committee members are on their 40th file of the day. They’re tired. The earlier, clean, well-organized applications get more mental space. The later, confusing files get “table until next month” or a quick deny with a vague explanation.

Your job is to make your file frictionless to read:

- Clear headings.

- One primary evaluator report instead of six competing letters.

- A cover letter or disability office summary that tells a coherent story: diagnosis → history → current impact → requested accommodations → rationale.

2. Program culture

Some schools lean supportive. Others treat accommodations like a threat to their “rigor.” You feel the difference immediately in the room.

Supportive culture:

- “Our job is to make sure qualified students are not blocked by barriers we can reasonably remove.”

- Will often ask, “How can we get this to yes in a defensible way?”

Defensive culture:

- “We can’t let this open the floodgates.”

- “If we grant this, we’ll have 20 more students asking for the same.”

- “Clinical competence can’t be accommodated away.”

You can’t fully control culture. But you can counter some of it with documentation that clearly addresses safety, competency, and standards.

3. Faculty pushback behind the scenes

Clinical departments sometimes push back on certain accommodations:

- Extra time on OSCEs? They worry it doesn’t reflect real clinical pace.

- Modified call schedules? They worry about fairness and coverage.

- Reduced patient loads? They worry about training volume.

What happens is the disability office or ad‑hoc committee quietly pre‑filters requests to avoid a fight with powerful departments. They’ll say “not recommended” or “not reasonable in this setting” even before it reaches the specialty faculty.

Again, documentation that frames accommodations as enabling core competencies, not lowering them, reduces friction. For instance, framing extra time in written exams as measuring the same knowledge without penalizing a processing speed deficit—while clearly acknowledging that clinical pace expectations will remain intact.

What “Enough” Documentation Actually Looks Like

Let me sketch what “enough” looks like from the inside for a typical med student with ADHD or a learning disorder seeking extra time on high-stakes exams.

| Aspect | Strong File | Weak File |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Full neuropsych eval, named tests, DSM criteria | Brief note, no tests |

| Recency | Within 2–3 years | 7+ years old |

| History | Prior IEP/504 and exam accommodations | No prior history mentioned |

| Objective Data | Percentiles, clear deficits | Vague descriptions only |

| Functional Impact | Concrete academic examples | General stress narratives |

| Nexus | Direct link from deficit to requested accommodation | “Would benefit from extra time” |

Picture a file that includes:

A neuropsychological evaluation (30–40+ pages) from the last 2–3 years.

- Cognitive scores.

- Achievement scores.

- Processing speed/working memory breakdown.

- Validity checks that indicate good effort.

- A clear diagnostic section referencing DSM-5.

A separate, concise clinician letter from a treating psychiatrist/psychologist that:

- Summarizes the condition and stability.

- Describes real-life academic and test impact with specific examples.

- States, in plain language: “Without extra time, this student is unable to complete board-style questions despite adequate content mastery.”

Verification of prior accommodations where possible:

- College or grad school disability office letters.

- Prior exam approvals (SAT, ACT, MCAT, NBME, etc.).

- Or, if none, an explicit explanation: late diagnosis, cultural/language barriers, stigma, or lack of access earlier. This matters. Silence is interpreted as absence.

A clean accommodation request form that:

- Specifies exactly what you’re asking for (e.g., 50% extra time, separate room, breaks).

- Ties each request to a documented impairment.

- Avoids overreaching. Asking for everything makes committees defensive.

When the file reads like a coherent narrative with data, history, and clear logic, the comment in the room is often something like: “This is well-documented. I’m comfortable approving.”

When it reads like a few vague letters stapled together, the comment is: “I’m not seeing enough here to justify this level of accommodation.”

How to Plug Holes in Your File Before They Use Them Against You

The worst time to discover your documentation is weak is after a denial from a national board. Appealing from behind is brutal. You want to plug holes proactively.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| 12-18 Months Before High Stakes Exam - Seek full evaluation | Start neuropsych or specialist assessment |

| 12-18 Months Before High Stakes Exam - Gather history | Request old IEP, 504, test records |

| 6-12 Months Before - Finalize report | Ensure detailed testing and functional impact |

| 6-12 Months Before - Coordinate letters | Ask treating clinicians for targeted letters |

| 3-6 Months Before - Align requests | Match accommodations to documented deficits |

| 3-6 Months Before - Submit early | Allow time for appeals if needed |

Here’s how insiders quietly coach students when no one is recording:

If your eval is thin, upgrade it.

- That two-page “ADHD form” from your PCP? Not enough for boards.

- Ask explicitly for a comprehensive evaluation with standardized tests.

- Tell the evaluator you will be using this for high-stakes exam accommodations so they know the level of detail required.

Force the functional impact section.

- Many clinicians write soft, generic letters. Push them (politely) to be concrete.

- Give examples from your own life: “When I take NBME-like practice tests, I leave 20–25% blank under standard time but complete them accurately with extra time.”

Build your longitudinal story.

- Hunt down any old school reports, teacher comments, SAT/ACT score breakdowns that show timing issues vs knowledge.

- If you lacked earlier diagnoses, get that explanation into the record. Cultural stigma, poor access, “I just worked 3x harder until it broke me in med school”—committees actually understand this when it’s spelled out by a professional.

Right-size your ask.

- If your data show mild deficits, 25% extra time is more defensible than 100%.

- If your anxiety is moderate but you’re not impaired on speed or reading, ask for separate room or breaks before asking for massive time increases.

Stop relying on “I’m anxious.”

- Anxiety alone, without clear functional impairment and treatment history, is one of the most commonly denied bases for extra time.

- If anxiety is secondary to another condition (ADHD, learning disorder, PTSD), get that primary condition properly documented.

The Future: Where This Is All Headed

You’re not imagining it—standards are hardening, especially for board-level exams. I’ve watched policies slowly shift from “let the school decide” to “prove it in our language, with our level of rigor.”

At the same time, institutions are getting more scared of litigation on both sides: from disabled students who are denied, and from others who claim unfair advantage. That makes committees behave like risk managers first, educators second.

Where things are trending:

- More standardized forms and checklists for evaluators.

- Less weight on “soft” letters and more on psychometric data.

- More emphasis on internal consistency: history, grades, previous exams, and current test results all have to tell the same story.

- Increased scrutiny of last-minute diagnoses timed to major exams.

If you want your documentation to be “enough” five years from now, aim higher than what barely passes today.

FAQs

1. My disability is real but I was high-achieving without accommodations for years. Will that hurt me?

It can, unless the record explains why. Committees routinely use prior success without accommodations to argue your impairment is not substantial. You need your evaluator to address this head-on: masking, overcompensation, unsustainable workloads, worsening demands in med school, or late recognition. A well-written explanation reframes your history as resilience under strain, not proof you never needed help.

2. Are short clinician letters ever enough without a full neuropsych evaluation?

For some conditions (certain physical disabilities, clearly documented psychiatric disorders with long treatment history), yes—for local exams, sometimes. For high-stakes exams and major time-based accommodations, almost never. Without objective testing or strong longitudinal data, committees feel exposed. A three-paragraph note saying “I know this student; they need extra time” is practically an invitation to deny.

3. How often do appeals actually work?

More often than students think—if you fix the original weaknesses. Appeals that just repeat “I disagree” go nowhere. Appeals that add a targeted, comprehensive eval, clarify functional impact, and tighten the nexus between impairment and requested accommodations get traction. I’ve seen initial denials turn into approvals when the second round of documentation was built strategically instead of hastily.

Key points: committees are not judging your worth; they’re judging the defensibility of your paperwork. “Enough” means strong diagnosis, clear impairment, concrete functional impact, and a tight logical link to each requested accommodation. Build your file like you expect someone hostile to read it—and you dramatically improve your odds of a yes.