You Hit “Post” After Your First Big Procedure

You scrub out from your first robotic cholecystectomy or a new catheter-based valve procedure. Adrenaline still high. You crushed it. Or at least, you didn’t crash the patient.

You get to the lounge, open Instagram or TikTok, and there it is:

A blank “create” screen. You type:

“Just did my first [procedure name] solo! Love being on the cutting edge. #innovation #medlife”

Maybe you crop out the face, maybe you blur a tattoo, maybe it’s just a shot of the monitor with a drape and some instruments. It feels…harmless. Educational, even. Everyone else posts this stuff, right?

Fast forward 3 weeks.

- The hospital compliance officer emails you: “Can we meet to discuss a social media concern?”

- Your PD has “heard from risk management.”

- A patient’s family member calls the clinic: “Is this our mom you posted?”

- A screenshot of your post is now in the legal chart of a complication.

This is how fast it goes from “cool” to “career-damaging.”

Let me be blunt: posting about new procedures on social media is one of the easiest ways for a well-meaning, competent trainee or young attending to wreck trust, trigger an investigation, and potentially invite legal trouble. You don’t have to violate HIPAA obviously for this to backfire. The bar is lower than you think.

Let’s walk through how this goes wrong, why “everyone else does it” is a lie, and what you should absolutely not do if you care about your license, your reputation, and your patients.

The First Big Mistake: You Think De-Identification Is Easy

You’ve heard it before: “Just remove the name and face and it’s fine.” Wrong. That’s the rookie mistake that burns people.

How you accidentally identify a patient

These are classic ways I’ve watched smart people get in trouble:

- Posting a shot of a unique tattoo, piercing, or birthmark.

- Captioning something like:

“54-year-old unvaccinated male with BMI 42 and no prior surgeries, first case of XYZ at our center.” - Sharing a recognizable hospital room, date, and a rare condition in a small town.

- Including a monitor that shows date/time and MRN in the corner you didn’t notice.

- Posting a “before/after” of a rare congenital anomaly on the exact day the local news reported it.

You don’t need a name tag for a patient to be identifiable. “Reasonably identifiable” is enough. The combination of age + rare condition + date + location can absolutely point to a single person.

Why new or “first” procedures amplify the risk

New procedures are, by definition, uncommon. That makes patients easier to identify.

If you publicly post:

“First totally percutaneous mitral valve repair at [small community hospital]!”

Anyone in that community who knows a person having that exact procedure that week can connect the dots. Family members. Nurses. Even the patient themselves.

Now pair that with any clinical detail and you’re past the “oh I didn’t mean to” line and into regulatory/ethical mess.

The Ego Trap: Turning a Patient Into Your Personal PR Campaign

This is the ethical failure most people don’t admit to. You’re not just “educating” when you blast your new skill online. You’re often marketing yourself. The problem is whose body you’re using to do it.

How it looks from the patient side

You may think:

“I’m proud of expanding access to this cutting-edge intervention.”

The patient or their family may think:

“So I was basically a case for their social media brand?”

That’s how trust dies.

Especially bad moves:

- Posting before a complication has fully declared itself.

- Posting while the patient is still in the ICU.

- Posting with triumphant language: “Crushed this!” “Epic save!” “Love this cool device.”

Because if that patient has a stroke, infection, or dies, the family now sees your “epic save” TikTok in a completely different light. And yes, lawyers will see it too.

Legal and Regulatory Landmines You’re Underestimating

You’re not just up against “HIPAA bad.” You’re up against institutional policy, professional boards, and the court of public opinion.

| Source of Trouble | What Triggers It |

|---|---|

| HIPAA / Privacy laws | Identifiable patient info or images |

| Hospital policies | Posting about cases without permission |

| Licensing boards | Unprofessional online conduct |

| Malpractice litigation | Posts used to question judgment/consent |

| Public/media backlash | Perception of exploitation or showboating |

How even “anonymous” case posts end up in legal files

Plaintiff attorneys love screenshots. I’ve seen cases where:

- A surgeon’s “we did everything we could” defense was undermined by their own captioned post bragging about balancing 4 complex cases that day. Looks like overextension.

- A “first time trying [device]” comment was used to argue inadequate disclosure of surgeon inexperience during consent.

- A resident’s Tweet about being “so exhausted post-call but still in the OR” came back during a bad outcome review.

You thought it was just a 24‑hour Story. It became Exhibit 7.

Informed Consent: What You Think You Said vs. What You Actually Said

One of the dirtiest hidden problems with posting about new procedures: consent mismatch.

The silent assumption you’re making

You may think:

“They signed a generic consent. They know this might be used for education.”

No. They did not consent to become content for your personal brand, Instagram account, or TikTok channel.

- “Educational use” in institutional forms usually refers to controlled settings: conferences, de-identified lectures, sometimes internal teaching.

- Public-facing social media under your name, with hashtags and followers? Not the same.

Unless your consent form explicitly states social media posting, with the platform and purpose made clear, and the patient still agrees, you are on very thin ethical ice.

And even if the form exists, you need to ask yourself a harder question: Would this patient feel pressured to say yes because you’re the surgeon? If the answer is “probably,” you’re already veering toward exploitation.

The “Innovation” Halo That Makes You Sloppy

New procedures come with hype. Press releases. Internal emails. People calling you “cutting edge.” That halo easily blinds you to basic guardrails.

Three patterns I keep seeing with “innovative” posts

Overclaiming success

- “Revolutionary new procedure that eliminates the need for open surgery.”

- Problem: you have n=3 and 6‑month follow-up.

- This looks like misleading advertising, especially if you’re in private practice.

Underplaying uncertainty

- “Game changer for patients who had no options before.”

- Reality: options existed; they were just higher risk or less convenient.

- You’re misrepresenting the risk/benefit balance publicly.

Subtle self-promotion

- “Honored to be the first in my region to offer [procedure]. So proud of our team.”

- On its own, maybe harmless. But layer in case details or semi-identifiable images and it becomes clear: this is marketing, not pure education.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Education | 25 |

| Self-promotion | 40 |

| Peer validation | 25 |

| Institutional pressure | 10 |

Let me be direct: regulators and hospital lawyers read these very differently than you and your co-fellows do.

Institutional Politics: You’re Not Just Risking Yourself

You post something dumb, you don’t just put your name at risk. You drag your department, your hospital, and sometimes your specialty into the mess.

How institutions react when they feel blindsided

Common sequence:

- Your post gets reported by:

- A nurse who thinks it crosses a line.

- A competing doc who doesn’t like you.

- A patient who recognizes themselves.

- Risk management and legal review the post.

- They discover:

- No media clearance.

- No institutional branding review.

- No documented social media training.

- Result:

- Mandatory social media policies tightened.

- All “educational” posting suddenly banned or choked with bureaucracy.

- You’re the reason everyone gets an angry all-staff email.

Is that fair? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. But it happens. I’ve watched a single arrogant “first case at our center!” tweet kill a useful departmental case-discussion account that had run quietly and responsibly for years.

The Fake Safety of “Professional” Accounts

You might be thinking, “I use a professional separate account. Patients don’t follow me there.”

That’s adorable. And wrong.

Why your “med Twitter” or “doctor Insta” isn’t a safe bubble

- Patients search your name.

- Reporters search hashtags.

- Hospital admin tracks public mentions of their institution.

- Screenshots move between platforms without your control.

Your “@DrNewProcedure_MD” account is still you. Boards, hospitals, and courts won’t care that you labeled it “views my own.”

If anything, having a dedicated account for “procedural content” can look worse, because it signals intent and pattern.

The Line Between Real Education and Creepy Voyeurism

There is a place for educational content. But people cross the line into spectacle constantly, especially with new shiny procedures.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: if your post is more about how impressive the tech looks than about thoughtful teaching, you’re drifting into voyeur territory.

Educational context vs. spectacle

Ask yourself, before you post:

- Is this genuinely teaching something that’s hard to learn elsewhere?

- Would I say these exact words, with this exact image, at grand rounds in front of:

- The patient

- Their family

- The hospital CEO

- A journalist

- If the patient saw this and knew it was them, would they feel:

- Respected?

- Neutral?

- Used?

If the answer is “used” even 10% of the time, delete the draft.

Concrete Scenarios Where Posts Blow Up (That You Probably Haven’t Thought Of)

Let’s get specific. These are scenarios I’ve actually seen or heard about, with identifying details changed.

Scenario 1: The proud fellow and the complicated TAVR

- A cardiology fellow posts a Story: “First TAVR as primary operator! Thanks to my attending for letting me drive.”

- Patient develops a stroke 2 days later.

- Family finds the fellow’s Instagram via hospital website bio.

- They see the Story (someone screenshotted it).

- In the complaint, they say: “We were not told this was his first time doing this.”

- Now you have:

- A consent question.

- A supervision question.

- A professionalism question.

Even if consent and supervision were fine, that Story became a weapon.

Scenario 2: The “innovative” plastics case

- Plastic surgeon shares before/after photos of a novel reconstructive technique.

- Patient signed a general photo consent but never had TikTok or Instagram specifically explained.

- A coworker recognizes the patient’s body from tattoos, even though the face was cropped.

- Patient finds out from the coworker, not the surgeon.

- The complaint isn’t just about privacy. It’s about deception and disrespect.

You can “win” the HIPAA battle and still lose the “basic human decency” war.

Scenario 3: The resident with the “funny” rare case

- Resident posts on Twitter: “Wild case today: 19-year-old with [extremely rare condition] at [city name] ED. Haven’t seen this since med school.”

- The condition is rare enough that basically only one person in that area has been in the news for it.

- A friend of the patient sees the tweet, connects the dots, tells the family.

- Hospital gets dragged publicly for “mocking” or “sensationalizing” a vulnerable patient.

No faces. No names. Still a mess.

Safer Alternatives If You Actually Want to Teach

You don’t have to disappear from the internet. You just have to stop gambling with live clinical cases and fresh procedures.

Here’s what’s safer and smarter:

1. Use heavily de-identified, delayed cases

- Wait months or years.

- Change multiple non-critical details (age range, sex, timing).

- Never mention “first,” “only,” or “this week” details.

- Strip out anything that points to a specific person or date.

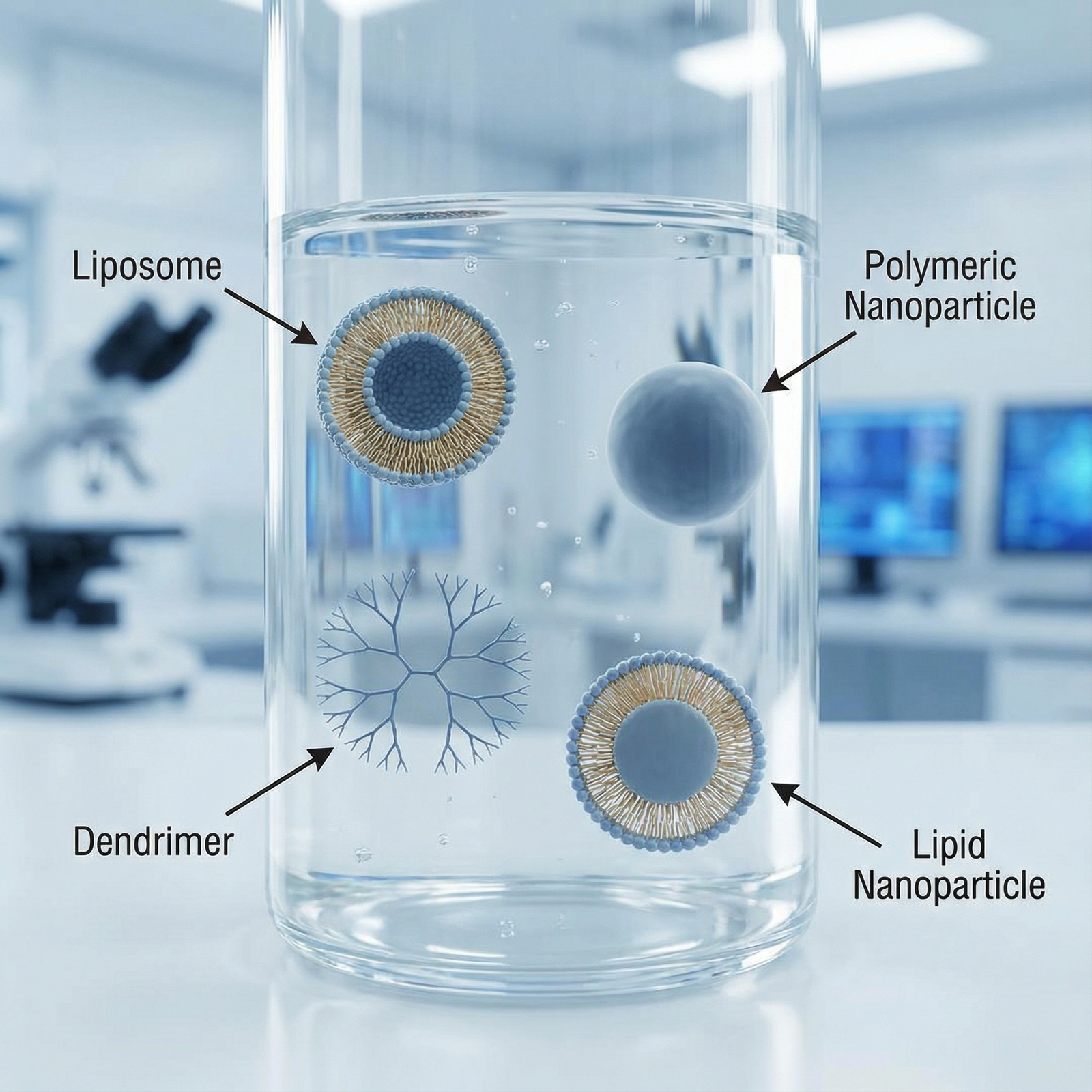

2. Use drawings, schematics, and models

Want to talk about a new procedure?

- Use anatomical diagrams.

- Use device manufacturer animations (with permission).

- Use whiteboard drawings or 3D-printed models.

You don’t need the actual patient’s imaging or photo to explain a concept.

3. Stick to published data, not live bragging

Better content:

- “Here’s what the latest trial shows about outcomes with [procedure].”

- “Here’s how patient selection for [new technique] is evolving.”

- “Here’s what I discuss with patients when we consider [approach].”

No individual patient needed. No HIPAA tension. Still useful.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Want to post about new procedure |

| Step 2 | Do not post |

| Step 3 | Safer to share |

| Step 4 | Delay and deidentify heavily |

| Step 5 | Reevaluate with mentor or legal |

| Step 6 | Includes real patient info or images |

| Step 7 | Uses diagrams or trials only |

4. Get institutional media involved for true “firsts”

If your hospital wants to publicize a “first in region” procedure:

- Let their media team handle consent, scripting, and images.

- Let them own the risk.

- You can reshare their polished, vetted output instead of freelancing your own.

Yes, it’s less exciting and more sanitized. That’s the point.

Personal Boundaries: Protecting Your Own Mind (Not Just Your License)

There’s another angle people ignore: what this constant posting does to you.

If every “win” becomes potential content:

- You start seeing patients as opportunities.

- You unconsciously prefer “interesting” or photogenic cases.

- You chase novelty over judgment.

For your own development as an ethical physician, you need a clean line in your mind:

Patients are not raw material for my brand.

Because once you cross that, it’s very hard to walk it back.

A Quick Personal Checklist Before You Ever Post About a Procedure

If you insist on posting anything even adjacent to procedures, run through this, ruthlessly:

Could a non-clinical person who knows the patient recognize them from this?

If yes, don’t post.Would I be completely comfortable reading this out loud to the patient and their family, in the hospital lobby, on camera?

If no, don’t post.If this case had a bad outcome tomorrow, would this post look insensitive, arrogant, or misleading?

If maybe, don’t post.Did any institutional or media professional review this?

If no and it includes anything clinical, don’t post.Am I more excited about what this does for my ego than for anyone’s education?

If yes, close the app.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Real-time case details | 95 |

| Same-week patient images | 85 |

| De-identified case weeks later | 40 |

| Diagrams and trial discussion | 10 |

The Bottom Line: Don’t Be the Lesson Everyone Else Learns From

If you remember nothing else, keep these three points:

“De-identified” is not what you think. New or rare procedures make patients much easier to recognize. If a reasonable person could connect the dots, you’re exposed.

Your pride post can become Exhibit A. Bragging about “first,” “solo,” “exhausted,” or “epic” around new procedures is how you hand lawyers and licensing boards ammunition for free.

Patients are not content. If you’re building a reputation as an ethical, trusted physician, treat every urge to post about live procedures with suspicion. When in doubt, do not hit “post.”