Building a Remediation Curriculum for Struggling Medical Students

It is late May. Promotion committee meets next week. You have three students on the agenda: one who barely passed Step 1 on the second try, one who failed two clerkship shelf exams, and one with repeated unprofessional behavior notes. Your dean looks at you and says, “You’re overseeing remediation this year. We need a real curriculum, not ad hoc tutoring. What’s the plan?”

This is where most schools are right now. Lots of good intentions. Very little structure. And a whole lot of “we’ll just assign them to work with Dr. X and hope it gets better.”

Let me break this down properly. You are not “helping weak students study harder.” You are designing a parallel curriculum with its own goals, assessments, and faculty skill set. If you treat remediation as a loose collection of favors, you will keep getting the same outcomes: burnout, repeat failures, and committees that feel like they are guessing.

We will walk through how to build a remediation curriculum that is:

- Systematic, not ad hoc

- Differentiated by problem type (knowledge vs skills vs professionalism)

- Measured with real outcomes, not vibes

And yes, I am going to be blunt about what usually goes wrong.

Step 1: Define What “Struggling” Actually Means

The biggest failure point is upstream: vague identification. If your “struggling student” category is “anyone faculty are worried about,” you cannot build a coherent curriculum.

You need explicit triggers. Written. Endorsed by your curriculum committee. Shared with course and clerkship directors.

Think of three broad domains:

- Cognitive / knowledge

- Clinical performance / skills

- Professionalism / behavior

Within each domain, define entry thresholds for remediation.

| Domain | Trigger Example | Typical Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Course or exam failure | <70% or below campus standard |

| Clinical skills | Failing OSCE station or clerkship block | F grade or repeated marginal |

| Professionalism | Recurrent concerns, formal incident | 2+ documented events / year |

This is the minimum. Better programs go further and use early warning triggers, for example:

- Two or more quiz scores in the bottom 10% of the class

- NBME subject scores < 5th percentile even if the clerkship is “pass”

- OSCE performance showing pattern failures (e.g., communication or physical exam)

- Multiple “areas for improvement” comments with similar themes across rotations

The point: make identification algorithmic enough that a student cannot slip through for 3 semesters before anyone officially intervenes.

And write the thresholds as policy. If your promotions committee has to reinvent criteria for each student, you are not running a curriculum. You are doing case-by-case triage.

Step 2: Build an Intake and Diagnostic Process (Not a Single Meeting)

Most schools’ “intake” is a 30–60 minute meeting with an Associate Dean who gives advice and maybe a PDF of study tips. That is not diagnostic. It is generic counseling.

You want a structured intake that covers three layers:

- Performance mapping

- Learning and cognition

- Context and functioning (life, health, accommodations)

1. Performance Mapping

You start with data, not feelings.

- List all courses, clerkships, exams (with dates and scores)

- Highlight failures, near-failures, and downward trends

- Classify issues: broad underperformance vs specific domains (e.g., cardiology, clinical reasoning, test-taking)

If you have NBME score reports with content-area breakdowns, use them. Look for patterns: persistent weakness in pathophysiology? Behavioral science? Pharmacology? Or is everything low?

2. Learning and Cognition

Then you sit down with the student and dissect how they are learning. Not just “how many hours did you study.”

Key questions:

- Describe what you actually do in a 2-hour study block. Minute by minute.

- When you watch a lecture, what happens afterward? Do you take notes? Do you convert them into questions?

- How do you review old material? Be specific.

- For practice questions: how many per day? How do you review explanations? Do you track errors?

- How do you decide what to study tomorrow? By schedule? By mood? By perceived weakness?

If every answer is vague (“I review my notes a lot,” “I do some UWorld questions when I can”), you already have your first remediation target: study process.

For some students, you should push for formal cognitive/psychological evaluation:

- Multiple failures despite high apparent effort

- Longstanding history of “slow reading,” extreme test anxiety, or focus problems

- Marked contrast between in-person performance and standardized tests

Do not try to be the neuropsychologist. Your job is to recognize when the usual “try Anki” script is not enough.

3. Context and Functioning

This part makes or breaks remediation.

I have seen students with three failed clerkships turn it around fully once their untreated depression and insomnia were addressed. I have also seen students with perfectly normal mood who just never learned how to study above an undergraduate “cram and pass” level.

Ask directly (and non-judgmentally):

- How are you sleeping? Average hours, consistency.

- Are you using substances to cope, or to stay awake?

- Any major life events over the last year? (Family illness, finances, relationship breakdown)

- Current therapy, medications, or disability accommodations?

Then write a brief intake summary that categorizes:

- Primary academic problem(s)

- Contributing personal/health factors

- Resources already in place

- Urgent risks (e.g., untreated mental health issues, unsafe coping behaviors)

That intake summary becomes the backbone of the remediation plan. Without it, you are guessing.

Step 3: Decide What Type of Remediation Track They Need

Do not treat all struggling students with the same “study skills” boot camp. That is lazy design.

You should have at least four distinct remediation tracks:

- Basic science / pre-clinical knowledge remediation

- Clinical reasoning and clerkship performance remediation

- Test-taking / high-stakes exam remediation (e.g., Step)

- Professionalism / behavior remediation

Most students will sit at the intersection of two.

Track 1: Basic Science Remediation

Target: Students failing courses, struggling with content-heavy exams, pre-clinical years.

Core elements:

- Content triage: focus on core organ systems and high-yield pathophysiology first.

- Explicit instruction in spaced repetition and retrieval practice, not just “try Anki.”

- Required question-based learning (small daily quotas with performance review).

- Weekly or biweekly faculty-guided case sessions that integrate physiology, pathology, and pharmacology.

What this is not: more lectures. If your solution to failure in lecture-based courses is “watch the lectures again with a tutor,” you are just amplifying a problem.

You want the curriculum to push them from passive to active:

- Instead of “review endocrine,” they must write 10 board-style questions on diabetes pathophysiology and explain each answer aloud.

- Instead of rewriting notes, they create concept maps and compare them in small groups.

- Instead of “read the chapter again,” they must do a block of 20 questions and categorize every error.

Track 2: Clinical Reasoning and Clerkship Remediation

Target: Students with failing or marginal clinical evaluations, OSCE failures, or poor shelf performance despite adequate basic science background.

This is where most schools are weakest. They conflate “remediation” with “repeat the clerkship and hope the student just matures.”

That is not a curriculum. That is time.

You need structured components:

- Direct observation: at least several observed patient encounters per week with focused feedback on history, physical, and presentation.

- Clinical reasoning seminars: small group sessions where students build problem representations, differential diagnoses, and basic management plans from vignettes.

- Documentation practice: supervised writing of notes with templated feedback (organization, assessment quality, clinical thinking).

- Communication skills work: targeted sessions on structuring oral presentations, patient counseling, and interprofessional communication.

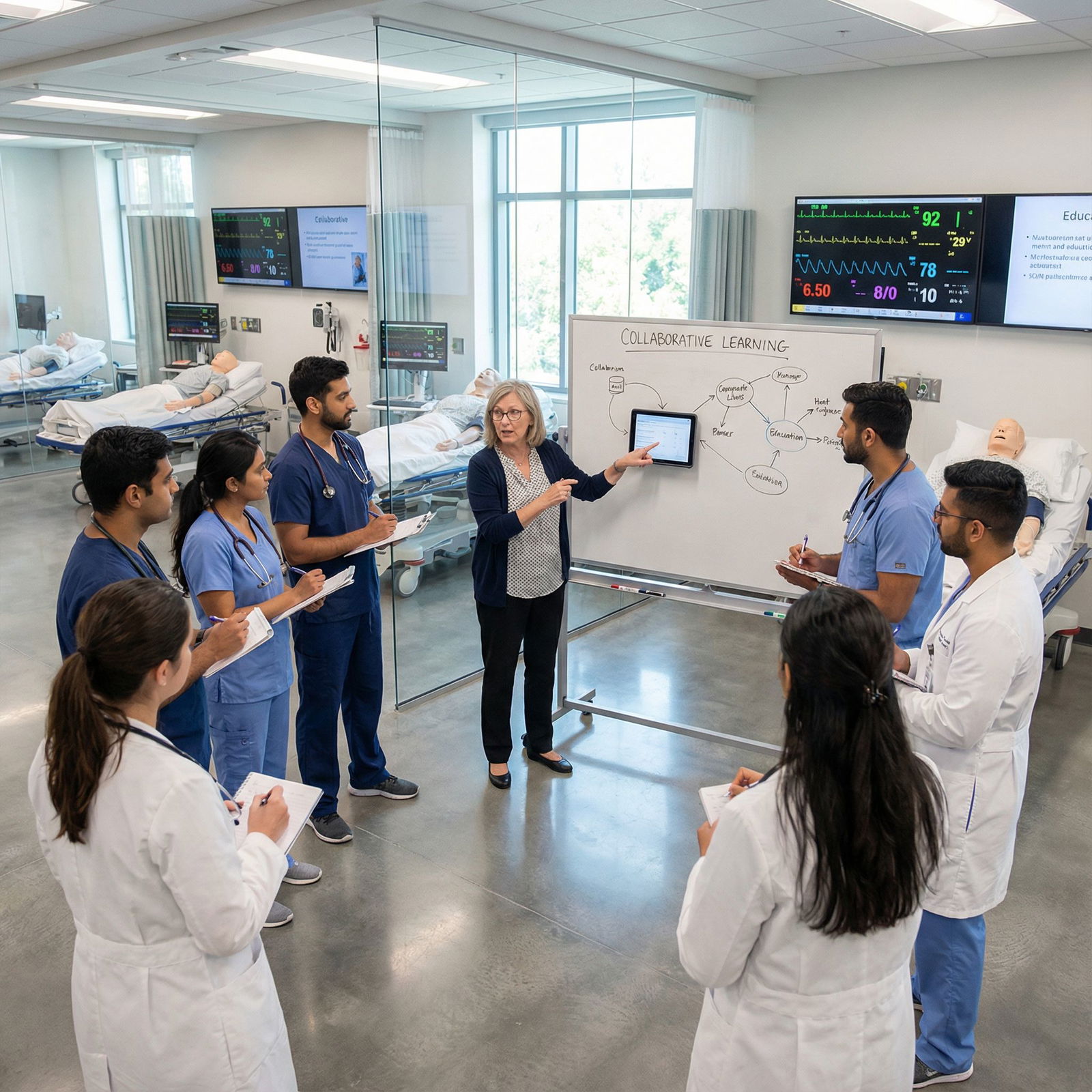

Better programs also use simulation:

- Focused OSCE stations reflecting the student’s weak areas (e.g., abdominal exam, difficult conversations).

- Standardized patients with scripted feedback.

Structure matters. You should be able to show a weekly schedule that looks like a mini-clerkship with higher density of feedback, not just “assigned to Dr. Jones for an extra rotation.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Week |

| Step 2 | Assign 2 Observed Encounters |

| Step 3 | Schedule 1 Simulation Session |

| Step 4 | Set Question Bank Targets |

| Step 5 | Daily Feedback Review |

| Step 6 | End of Week Case Conference |

| Step 7 | Adjust Next Week Plan |

Track 3: Test-Taking / High-Stakes Exam Remediation

Target: Students failing Step/NBME exams with otherwise adequate classroom or clinical performance.

Do not confuse this with “low scores.” Curriculum is for those at risk of dismissal or delayed graduation.

This track has three pillars:

- Knowledge consolidation (they still need content)

- Cognitive approach to questions

- Exam behavior and logistics

Concrete components:

- Diagnostic question block review: sit with the student through a 20–25 question block, have them verbalize thinking on each question. Identify where the process breaks: misreading stem, jumping to first pattern match, not using options, time mismanagement.

- Teach a structured question approach (e.g., read stem, identify task, generate hypothesis before looking at options, eliminate systematically).

- Weekly performance dashboard: number of questions done, percent correct, question categories, and timing.

- Simulated full-lengths scheduled and debriefed, not optional “do one if you can.”

You will often discover that what the student calls “test anxiety” is actually “I do not have a reliable question strategy and panic when I realize I am guessing.” Fix the strategy first.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | 42 |

| Week 2 | 51 |

| Week 3 | 58 |

| Week 4 | 63 |

| Week 5 | 68 |

Track 4: Professionalism / Behavior Remediation

Target: Students with patterns of:

- Repeated tardiness or absenteeism

- Disrespectful communication or boundary issues

- Dishonesty, cutting corners, or charting concerns

Schools either go too soft (“write a reflection essay”) or too punitive (“one more misstep and you’re gone”) without a real developmental plan.

An actual curriculum here includes:

- Behavior-specific coaching: not “be more professional,” but “you must learn specific behaviors for email etiquette, handling criticism, and meeting deadlines.”

- Clear expectations contract: timelines, metrics, and examples of acceptable and unacceptable behaviors.

- Required reading or modules on professional norms, ethics, and team behavior. Yes, some students truly do not know what is standard.

- Regular check-ins with a designated professionalism mentor (not necessarily the Dean).

And zero tolerance for hiding. Professionalism remediation has to be documented and shared with relevant stakeholders, or it becomes a secret side deal with no accountability.

Step 4: Build a Structured Remediation Plan Template

Every student should have a written remediation plan that could be handed to another faculty member and still make sense.

At minimum, your template should include:

- Student identifiers and key context (year, curriculum phase, prior failures)

- Problem statement (no more than 3 sentences, specific)

- Remediation goals (SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound)

- Activities (what, how often, with whom)

- Assessment methods and benchmarks

- Timeline and decision points

- Contingency outcomes (what happens if benchmarks are not met)

Example (simplified):

- Problem statement: “M3 student with two failed IM/Neuro shelf exams and observed difficulty in structuring differential diagnoses and oral presentations.”

- Goals during 8-week remediation block:

- Achieve ≥60th percentile on IM NBME by week 8

- Demonstrate structured problem representation and 3-item prioritized differential in 80% of observed presentations

- Activities:

- 3 half-days per week in IM clinic with required 2 observed presentations per day

- Twice-weekly clinical reasoning small group (case-based)

- 30 NBME-style questions daily with weekly faculty review of missed items

- Assessment:

- Weekly OSCE-like micro-assessments (short cases)

- Faculty evaluation form with specific anchors for reasoning and communication

- NBME practice test at weeks 4 and 8

You store these plans in a central remediation database, not scattered emails. If your process depends on one Associate Dean’s memory, it is fragile and non-scalable.

Step 5: Decide Who Teaches – And Train Them

Not every excellent clinician is a good remediation faculty member. In fact, some of the most brilliant specialists are absolutely terrible at working with struggling students. They think “I just did more questions and read First Aid; why cannot you?”

You need a defined remediation faculty pool with:

- Patience and ability to verbalize their own cognitive processes

- Comfort giving direct feedback without shaming

- Willingness to collaborate across basic science and clinical teams

And then you train them. Briefly but deliberately.

Core training topics (90–120 minutes, not a 10-minute hallway chat):

- Basics of adult learning and why struggling students need different approaches

- How to give feedback that is specific and actionable (not “you need to be more confident”)

- Recognizing when a student’s problem is beyond “study harder” (mental health, disability)

- How to document sessions concisely and clearly

You do not need everyone to become an education PhD. You just need them to stop doing the worst things:

- Telling a student they “just need to be more motivated”

- Assigning random extra readings without assessment

- Providing only global pass/fail impressions instead of behavior-specific feedback

Compensate them in some form: FTE, teaching points, promotion criteria. Remediation work is demanding and emotionally heavy. If you treat it as invisible service, it will be done by the same two burned-out people forever.

Step 6: Build Assessment and Exit Criteria

Remediation without clear outcomes is just nicer-sounding probation.

You need:

- Formative check-ins

- Summative decision points

- Exit criteria that are transparent

Formative Check-ins

Set specific timepoints where you formally review progress. Weekly for shorter interventions, monthly for longer ones.

At each check-in, ask:

- Are scheduled activities actually happening? (attendance, logs)

- Are process behaviors changing? (e.g., use of question review logs, adoption of a note template)

- Are outcome metrics trending in the right direction? (scores, observed performance ratings)

Use simple visual tracking when possible.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Baseline | 58 |

| Week 2 | 68 |

| Week 4 | 74 |

| Week 6 | 81 |

If there is no improvement by mid-course, you have to adjust the plan, not just hope the curve suddenly bends later.

Summative Decision Points

Promotions and remediation committees should see more than “the faculty feel better about the student.”

Provide:

- Concrete pre/post comparisons (exam scores, OSCEs, faculty ratings with anchors)

- Narrative summaries documenting observed behavior change

- Student self-reflection tied to specific goals, not generic “I learned a lot.”

Decide beforehand what constitutes:

- Successful remediation and promotion/return to standard curriculum

- Partial success requiring extended or modified plan

- Failure of remediation leading to repetition, leave, or dismissal discussions

Write these decisions into your policy. Otherwise, you end up with committee meetings driven by emotion and fear of litigation rather than structured outcomes.

Step 7: Integrate Support Services Without Dumping Everything on the Student

Remediation is not just academic. For many students, academic performance is a symptom.

You should build default linkages to:

- Counseling and mental health services

- Disability services / accommodations review

- Financial aid (for students needing to delay graduation or add tuition-bearing time)

- Student affairs for housing, leave of absence, or personal crises

Notice I said default. Students do not reliably self-refer. Your intake process should include actively offering warm handoffs like:

- “I am going to send a message to our counseling center with you cc’d so they know you are a remediation student and can prioritize scheduling.”

- “Let us review what documentation disability services would need, and I will introduce you to their director.”

If your remediation program acts like academic performance exists in a vacuum, you will keep “failing” students whose actual barrier is untreated ADHD, major depression, or caregiving responsibilities.

Step 8: Data, Quality Improvement, and Program Survival

A remediation curriculum that cannot prove its value will be one of the first things cut when budgets tighten.

So you collect data. Routinely.

Basic metrics to track year over year:

- Number of students entering remediation, by track and year level

- Completion rates of remediation plans

- Pre/post exam score changes (absolute and percentile)

- OSCE/clinical evaluation changes

- Downstream outcomes: repeat failures, delayed graduations, dismissals

| Metric | Year 1 | Year 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Students in remediation | 24 | 31 |

| Completed remediation | 18 | 26 |

| Average NBME score gain (pts) | +7 | +11 |

| Delayed graduations | 6 | 4 |

| Dismissals after remediation | 3 | 2 |

You also gather qualitative data:

- Faculty satisfaction with the process

- Student perceptions of fairness and usefulness

- Promotions committee confidence in remediation recommendations

Then you make visible changes based on those data. For example:

- If students in clinical reasoning remediation keep failing shelves, maybe you need more structured shelf prep integrated into that track.

- If professionalism remediation students keep reoffending, your expectations contract is probably too vague or unenforced.

Show this to leadership annually. Remediation is politically vulnerable; evidence buys protection.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Before Program | 82 |

| Year 1 | 87 |

| Year 2 | 90 |

| Year 3 | 92 |

Common Pitfalls (And How to Avoid Them)

I will be direct. These are the mistakes I see over and over.

Remediation as punishment instead of support.

Students feel that being “sent to remediation” is the first step toward dismissal, not an educational resource. Solution: frame it early and often as part of normal academic support, and make entry criteria transparent.Excessive customization with no standard structure.

Every student has a unique snowflake plan with 17 goals and no shared template. Faculty burn out; committees cannot compare outcomes. Solution: use standardized plan templates with room for specific customization.Faculty who will not give honest feedback.

“You’re doing better, keep it up” with no specifics is useless. Solution: train remediation faculty to anchor feedback to observable behaviors and standardized forms.No hard boundaries.

Students linger in perpetual remediation limbo, extending timelines repeatedly. Solution: set maximum remediation durations and clear criteria for what happens if goals are not met.Ignoring upstream curriculum problems.

If 20% of a class fails the same exam, you do not have 20% “struggling students.” You have a curricular design or assessment problem. Remediation data should loop back to curriculum reform.

Designing the Operational Flow

You also need to think about basic operational questions: who triggers what, when, and how often.

Here is a clean, minimalistic flow you can adapt.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Assessment Failure or Trigger |

| Step 2 | Automatic Flag in System |

| Step 3 | Remediation Intake Meeting |

| Step 4 | Return to Standard Curriculum |

| Step 5 | Assign Track and Faculty |

| Step 6 | Develop Written Plan |

| Step 7 | Implement Plan |

| Step 8 | Midpoint Review |

| Step 9 | Modify Plan or Extend |

| Step 10 | Summative Assessment |

| Step 11 | Successful Completion |

| Step 12 | Promotion Committee Review |

| Step 13 | Remediation Needed? |

| Step 14 | Progress Adequate? |

| Step 15 | Exit Criteria Met? |

Notice there are explicit decision points, not a vague “we will see how it goes.”

Two Realities You Need to Accept

Some students will not make it, even with a strong remediation curriculum.

Your job is not to rescue everyone at all costs; it is to give each student a reasonable, structured, and fair opportunity to meet the standards. Clarity and documentation protect both the student and the institution.Good remediation is resource-intensive.

There is no cheap, quick fix that works reliably. If leadership wants improved outcomes with minimal time, they are asking for magic, not education. Use your data to argue for the resources you actually need.

Key Takeaways

- Remediation must be a structured curriculum with defined tracks, not a set of ad hoc favors or generic “study harder” advice.

- Every student in remediation needs a written, time-bound plan with specific goals, activities, and assessment criteria that committees can actually use.

- The effectiveness of your remediation program lives or dies on three things: clear triggers, trained faculty, and honest data about outcomes.