The myth that promotions in medical academia are a clean meritocracy is comforting. It is also wrong.

Promotions are political, personal, and only partly about your CV. Chairs are not sitting with a checklist of H-indices and teaching awards, mechanically upgrading people at 5-year intervals. They’re asking one core question:

“Does promoting this person help or hurt my department?”

If you do not understand that lens, you will misread every signal, chase the wrong metrics, and hit an invisible ceiling you never see coming.

Let me walk you through how it actually works behind closed doors.

The Three Promotions That Are Not Really the Same

First, stop treating “promotion” like one thing. The rules change as you go up.

| Rank | Typical Title Examples |

|---|---|

| Entry | Instructor, Assistant Professor |

| Mid-career | Associate Professor |

| Senior | Professor, Full Professor |

| Leadership add-on | Division Chief, Vice Chair, Chair |

You’re really dealing with three distinct jumps:

- Instructor → Assistant Professor

- Assistant → Associate

- Associate → Full (Professor)

Each has a different unspoken standard.

Instructor to Assistant: The “We Hired You” Promotion

This one’s almost automatic in many places. You show up, don’t implode, pass your boards, and after 1–3 years you get bumped to Assistant.

What the chair is really looking for here:

- Are you clinically reliable?

- Do residents complain about you?

- Do you answer emails?

- Are you sane to work with?

This is HR plus basic professionalism. Your “productivity” is mostly RVUs and call coverage. Unless you’re in a pure research line, your CV barely matters yet; they already hired you based on potential.

Where people screw this up:

They think early promotion requires special favors. It doesn’t. It requires not being a problem. If you’re late, disorganized, or constantly canceling clinics, your title will lag.

But the real game starts at Assistant → Associate.

The Real Promotion: Assistant to Associate Professor

This is the filter. The moment when the chair decides whether you’re a long-term asset or just a warm body who will stay stuck at “career assistant.”

Publicly, the promotions handbook will say: excellence in some combination of clinical care, teaching, service, and scholarship. That’s the brochure.

Here’s what chairs actually ask in closed-door meetings before they sign your letter.

1. “What Type of Faculty Is This Person?”

Chairs mentally sort you into a lane by year 2–3:

- Research-track engine

- Education-track workhorse

- Clinician-educator hybrid

- Clinical revenue generator (aka “RVU mule”)

- Administrative fixer / future leader

- Dead weight

They then judge your promotion package against the lane they’ve assigned you. Not against the pure ideal in the handbook.

So if you’re labeled “clinician-educator,” no one expects 10 R01s. But they do expect:

- Concrete teaching roles (course director, clerkship lead, fellowship director)

- Solid evaluations from students/residents over several years

- Some scholarship that’s at least “educational products + a few papers or abstracts”

If you’re “research-track,” everything shifts. They will tolerate lower clinical output and fewer teaching awards if:

- You bring in money (grants)

- You publish regularly

- You show upward trajectory (e.g., K → R-level funding or equivalent)

The nuance: The chair’s private labeling of you is often never said out loud. But it drives everything.

If you do not know how your chair sees you, you are flying blind.

2. “Does This Person Make My Life Easier?”

I’ve sat in promotion discussions where the chair flips from hesitant to enthusiastic in one sentence:

“He saved our fellowship when we lost two faculty.”

“She took over the clerkship and stopped the LCME complaints.”

“He’s the one person the residents request on every rotation.”

The decision pivots not on some abstract metric, but on: are you solving problems for the department.

Chairs reward people who reduce their headaches. They stall or slow-roll those who create them.

The kinds of things that quietly count:

- You say yes to key departmental needs (within reason)

- You show up to big events (grand rounds, key retreats, accreditation visits)

- You’re not a constant source of complaints from nurses, APPs, or trainees

- You don’t start turf wars across divisions that the chair then has to mediate

None of that appears on the official promotion criteria. All of it is discussed in the hallway before the committee meeting.

3. “Is the Timing Right Politically?”

Here’s the part nobody tells junior faculty:

Sometimes your CV is good enough, and you still get told to “wait another year.”

Why? Politics and timing.

Common unseen factors:

- The department just had a slew of promotions and doesn’t want central administration asking why your unit suddenly has 25 new associates

- Your division chief is in conflict with the chair; the chair sits on their promotion recommendations

- The dean’s office is tightening standards for a couple of years after a perceived “too easy” cycle

- Budget and headcount concerns: promoting you may trigger salary adjustments or affect promotion stats that get scrutinized

Chairs will rarely say, “We need to spread these out for political optics.”

You’ll hear: “Let’s strengthen your teaching portfolio a bit more,” or “Another publication or two will make this bulletproof.”

Translation: Your file is fine. The context is not.

Smart move: Ask directly in a private meeting, “Is there any political or timing reason I should not go up this year?” A chair who respects you will usually give you a hint, even if they don’t spell it out.

The Top Rung: Associate to Full Professor

The jump to full is a different beast. It’s less about potential, more about sustained impact and reputation.

Here’s how chairs actually look at it.

1. “Is This Person Recognized Beyond Our Institution?”

Full professor is about stature. Chairs and deans ask: is this person a name in their niche, at least regionally, preferably nationally?

They look for signals like:

- Invited talks at other institutions

- Named roles in national societies (committee chair, board member, guideline author)

- Editorial board memberships or major guideline authorship

- Senior authorship on impactful papers, not just “another middle author” lines

Your external letters are key. Don’t underestimate this. Chairs think in terms of: if I promote this person, will outside people nod or raise eyebrows?

If your external reviewers write, “I know of Dr. X but have not directly interacted,” that’s lukewarm. They want, “Dr. X is widely regarded as a leader in Y.”

You get there by years of committee grunt work, national meeting presence, networking, and not flaking when others do.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Instructor→Assistant | 2 |

| Assistant→Associate | 7 |

| Associate→Full | 8 |

Does everyone fit these timelines? No. But these are the numbers chairs have in their heads when they think, “Is it too soon?”

2. “Do They Lead Something That Matters?”

Associate is about being very good. Full is about owning something.

Chairs look for ownership:

- You built or run a program (simulation center, new clinic, residency track, research core)

- You’re the go-to person for a specific clinical area, educational domain, or research niche

- Your name is tied to an initiative that clearly helps the department or school

If your CV is just “more of the same” from associate—same teaching, same publishing pace, same committees—that’s where people stall at the associate plateau.

I’ve watched candidates with decent publications and good teaching get held back because the chair couldn’t answer a simple question from the dean: “What are they known for?”

If your chair cannot answer that in one crisp sentence, your promotion to full will languish.

3. “Will Promoting This Person Lock Me In?”

Harsh truth: sometimes chairs hesitate because promoting you to full makes you harder to move, demote, or marginalize later.

So they ask themselves:

- Is this person aligned with where I’m taking the department?

- Are they a supportive citizen or a constant political problem?

- Would I regret giving them more status and leverage?

If you’ve made your chair’s life miserable—public opposition, constant sniping in faculty meetings, undermining initiatives—they may quietly slow-walk your file even if on paper you’re technically promotable.

No one writes that in the letter. But it’s discussed.

What Actually Gets Read in Your Promotion Packet

Here’s what committee members and chairs actually focus on when they skim your packet at 11:30 pm the night before the meeting.

1. The Chair’s Letter

This is your real currency.

Most committee members don’t know you. They rely heavily on the tone and specificity of your chair’s letter.

Red flags:

- Vague praise: “Dr. X is a dedicated clinician and valued member of our department.” Translation: nothing special.

- No concrete examples: no mention of programs built, courses led, grants landed, measurable outcomes.

- Hedged language: “I support Dr. X’s promotion” vs “I strongly and enthusiastically support…”

Strong letters have specifics: “She created the ultrasound curriculum now used by all 120 residents,” or “His clinic generated a 30% increase in new referrals and reduced readmissions by 15%.”

Your job for years before going up: give your chair material for those sentences.

2. The Personal Statement (and How Chairs Really React)

Most faculty treat the personal statement like a bad cover letter. Big mistake.

Insider detail: I’ve watched chairs roll their eyes at generic, “I have always been passionate about teaching” essays.

What they look for:

- A coherent story of growth: where you started, what you built, and where you’re going

- A clear theme: education leader, clinical program builder, national expert in X, etc.

- Evidence of reflection and direction, not just a list of activities rephrased in narrative form

Terrible move: trying to be everything. “I am a leader in clinical care, research, and education” when your CV shows one poster and average teaching scores. That disconnect makes chairs distrust your self-assessment.

Better: pick your lane, acknowledge the others, and show depth where you truly deliver.

3. CV Patterns, Not Just Totals

Chairs and committees scan for trajectory:

- Publications: one good paper a year beats six papers in 2016 and then nothing

- Teaching: sustained roles, not a random lecture every other year

- Grants: some sign you’re either bringing in money or contributing meaningfully to funded work

- Service: selective important committees, not 14 meaningless ones

They ask: is this person ascending, plateauing, or fading?

A slow but steady upward curve is fine. A burst then flat line raises questions like, “Are they already done growing?”

The Quiet Criteria No One Puts in Writing

Let me give you the subtler filters that come up in confidential conversations among chairs, division chiefs, and senior committee members.

1. “Do Trainees Want to Work With You?”

Trainees are noisy. And they’re listened to more than you think.

If repeated whispers show up like:

- “He’s great clinically but toxic on rounds.”

- “She’s brilliant but humiliates residents in public.”

- “We try to switch out of his clinic because he’s so disorganized.”

Those reputational hits absolutely affect how vigorously your chair will push for your promotion.

Conversely, if you’re the attending that residents protect, support, and cite as a reason they stayed in the program, that buys you more goodwill than one extra mid-tier publication.

2. “Are You an Energy Drain?”

Every department has faculty who are technically productive but utterly exhausting.

Constant complaints. Angry emails. Chronic opposition to any change. Every new initiative becomes a fight.

Chairs dread empowering these people with more titles and status. So even if they meet the stated criteria, the chair may respond with:

- “Maybe we should wait for one more national committee role.”

- “I think they’d benefit from another year of leadership development.”

Translation: I don’t want to reward this behavior yet.

If multiple leaders in your environment would describe you as “difficult,” don’t be shocked when your promotions move slower than your CV suggests.

3. “Will This Person Be Poached if I Don’t Promote Them?”

Here’s the leverage card that almost no junior faculty use well.

Chairs are more eager to promote people they’re afraid of losing.

If you’re getting calls from other institutions, invited for leadership roles elsewhere, or have clear alternative options, your chair sees risk. They know that failing to promote you sends a strong “we don’t value you” message that may push you out.

I’ve seen promotions that “suddenly” speed up right after a faculty member gets a serious outside offer.

No need to play games. But it’s not naive to let your chair know, candidly, “I’m being approached for X role at Y place, and I’d like to understand my long-term path here before I entertain that too seriously.”

Handled maturely, that gets attention.

How to Actually Position Yourself for Promotion (Not the Brochure Version)

Let me be concrete. What should you actually do starting early in your faculty career?

Pick and Own a Niche by Year 3

The faculty who glide through promotions are not the “do-everything-for-everyone” types. They’re the ones who are known for something.

Examples:

- Ultrasound education for residents

- Palliative care in the ICU

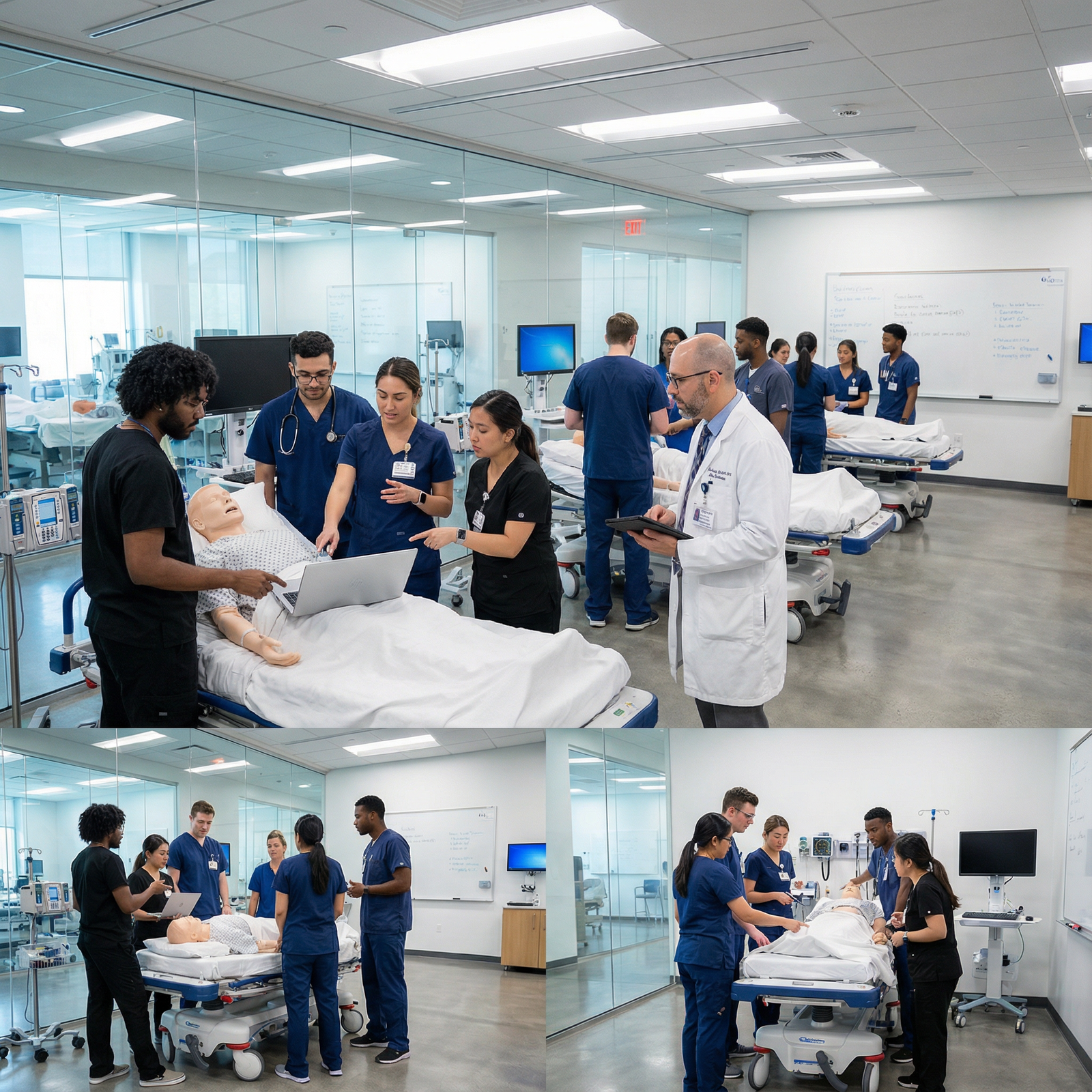

- Simulation-based crisis training

- Outcomes research in sepsis

- Quality improvement in perioperative medicine

By year 3 as Assistant, if someone asked your division “what’s her thing?” and the room goes silent, that’s a problem.

Pick a lane. Build visible work in that lane. Say no to side-quests that don’t fit, unless they’re politically necessary.

Cultivate Your Chair and Your Champions

You can’t ignore politics and expect merit to carry you.

- Meet with your chair or division chief at least annually to explicitly ask: “What will my promotion need to look like here?”

- Ask directly how they see your role: clinician-educator, researcher, program builder, or something else

- Request honest feedback, not fluff, and then visibly act on it

Also, cultivate 2–3 senior faculty outside your division who can vouch for you in committee discussions. Chairs look around the table and ask, “Who here knows Dr. X?” You want hands to go up.

Aim for Clear External Signals by Mid-Associate

By the time you’re thinking about going to full:

- Have at least 1–2 visible roles in national or regional organizations

- Be invited for talks at other institutions or major conferences

- Have one “signature” program, publication, curriculum, or clinic people associate with you

Do not assume local teaching excellence alone will carry you to full professor in most academic centers. It rarely does.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Hire as Instructor or Assistant |

| Step 2 | 2-3 years of clinical and teaching performance |

| Step 3 | Grants and publications |

| Step 4 | Teaching roles and curricula |

| Step 5 | Clinical volume and program building |

| Step 6 | Assistant to Associate review |

| Step 7 | Associate Professor |

| Step 8 | National reputation and leadership |

| Step 9 | Associate to Full review |

| Step 10 | Full Professor |

| Step 11 | Chair labels your role |

FAQ: How Promotions Really Work in Medical Academia

1. How early should I start talking to my chair about promotion?

By the end of your second year as faculty, you should have had at least one explicit conversation: “Where am I headed here, and what will a successful promotion look like for me?” Waiting until year six and then asking, “Am I ready to go up?” is how people discover they’ve been wandering off-track for years. Chairs will not always volunteer runway guidance—you have to pull it out of them.

2. Can I be promoted without research if I’m a pure clinician-educator?

Yes, but “without research” doesn’t mean “without scholarship.” Many institutions will promote strong educators who have produced curricular materials, teaching innovations, local QI work, or clinical guidelines that are presented, published, or shared beyond your own department. If your file shows zero scholarly contribution—no abstracts, no teaching scholarship, no written work—it’s an uphill climb, even if your evals are glowing.

3. What if my chair is weak or disengaged—am I just stuck?

A weak chair hurts you because that letter is your main advocacy. But you’re not powerless. Build allies among vice chairs, division chiefs, and senior faculty who sit on promotions committees. Document your impact clearly. And if your chair is truly nonfunctional, you’re often better off with an external move than waiting for them to be replaced. Plenty of solid faculty waste 5–7 years hoping a bad leader will magically become invested.

4. How do external offers affect my promotion prospects?

Serious external interest almost always strengthens your hand—if you’re already valued. Chairs don’t like losing productive faculty and will sometimes accelerate stalled promotions when they fear you may walk. But if your department quietly thinks you’re mediocre, flashing a weak outside offer can backfire and mark you as a flight risk without leverage. Use outside interest as a reality check, not a bluff.

Key takeaways: Promotions aren’t a clean scoreboard; they’re a judgment call filtered through your chair’s priorities, politics, and perception of your value. You need a clear niche and story, not just a pile of activities. And if your chair can’t answer, in one sentence, why promoting you will help the department, that’s the problem you need to fix first.