Only about 2–3% of malpractice cases actually hinge on “missing documentation,” while roughly 60–70% of adverse defense outcomes involve charts that are full of documentation—but internally inconsistent, copy‑pasted, or obviously bloated.

So no, stuffing the chart does not reliably protect you. It often does the opposite.

Let’s dismantle this myth the way an opposing attorney would dismantle your 13‑page daily progress note.

Where This Myth Came From (And Why It’s Outdated)

You’ve heard the lines in residency and beyond:

“Document everything—if it’s not charted, it didn’t happen.”

“Better to over‑document than leave something out.”

“Courts care about documentation more than anything else.”

I’ve sat in risk meetings where an older clinician literally said, “I just write more. That keeps me safe.” Everyone nodded. No one showed data.

Reality: malpractice law has evolved, EHRs have changed the game, and judges and juries are now suspicious of bloated, templated, or obviously defensive notes.

The core legal standard in malpractice in the US and most similar systems is still the same:

- Did you owe a duty of care?

- Did you breach the standard of care?

- Did that breach cause harm?

- Did the patient suffer damages?

Documentation isn’t its own separate element. It’s supporting evidence. That’s all. Courts care about what you did and reasoned, not how many words you poured into Epic at 1:37 a.m.

The myth comes from the pre‑EHR era, when brief, sparse notes really could create ambiguity about whether something happened. Today, with templated ROS, auto‑populated vitals, and copy‑forward H&Ps, the problem is the opposite: there’s too much text, and a lot of it contradicts itself.

What Courts Actually Do With Your Documentation

Let’s get concrete. Courts and plaintiff attorneys use charts in three main ways:

- To show what you actually did (orders, meds, timing)

- To probe your clinical reasoning (why you chose what you chose)

- To attack or bolster your credibility (whether you seem careful, honest, and consistent)

Notice what’s missing: nobody is giving you legal “points” for length.

Documentation as a weapon for the plaintiff

Here’s where “more documentation” backfires badly:

Inconsistent details.

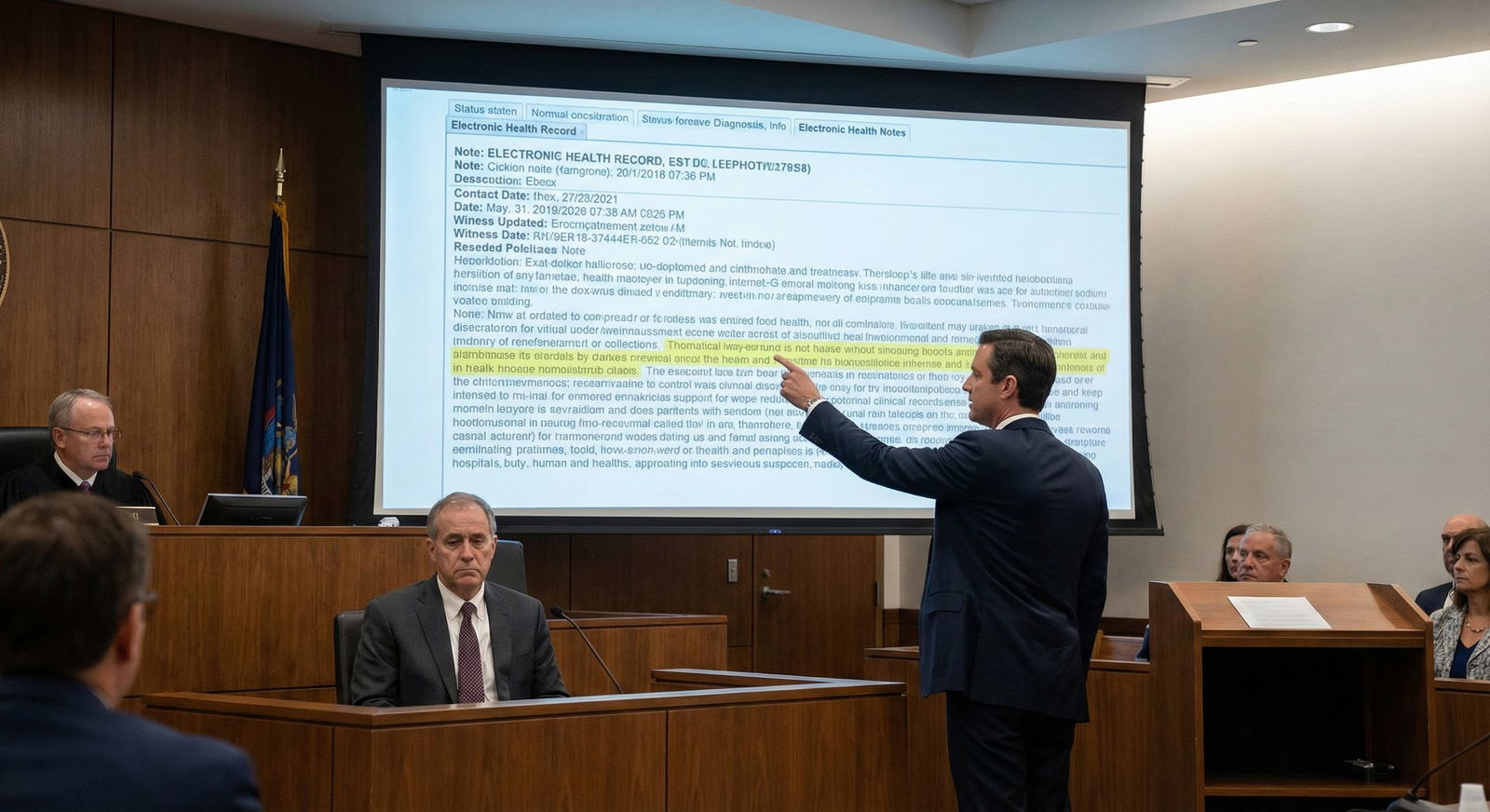

The ED note says “no chest pain.” The nursing triage note says “patient reports chest tightness with exertion.” The cardiology consult mentions “intermittent chest discomfort for weeks.” A plaintiff attorney will walk the jury through those contradictions slowly. With the chart up on a big screen. Your credibility decays with each slide.Clearly auto‑generated content.

The ICU progress note documents a 12‑point ROS as negative on a patient intubated and sedated on a vent. It says “no confusion, no shortness of breath, no fatigue” in a patient on norepi. Jurors aren’t dumb. They see nonsense. They think: If this part is obviously garbage, what else is?Copy‑paste timelines that don’t match reality.

Copy‑forward notes say “patient stable, tolerating PO, plan for discharge tomorrow,” while the vitals show a new fever and tachycardia, and nursing notes record escalating pain. That gap is a gift to the plaintiff.Overly rosy documentation conflicting with objective data.

I’ve seen notes that say “neurologic exam stable” while CT head shows new bleed and nursing notes document confusion. That sounds less like “busy clinician” and more like “covering tracks” to a jury.

Courts don’t punish you for not writing an essay. They punish you when the record undercuts your story.

What judges actually care about

In malpractice trials, judges give instructions to juries that usually sound like this (paraphrased, but I’ve seen versions of it):

“You may consider medical records as evidence of the care provided, but you are not required to accept everything in the record as accurate or complete. You should consider whether the records appear to have been made in the regular course of care, and whether they are consistent with other evidence.”

Translation:

- If your notes look routine, plausible, and consistent, they help you.

- If they look like they were written for a lawsuit—or are full of obvious EHR garbage—they lose credibility fast.

The “more documentation = more protection” crowd completely misses this nuance.

What The Data Actually Shows About Documentation And Risk

We don’t have randomized trials of “short vs long notes in court”, but we have enough malpractice data and EHR studies to see patterns.

EHR and malpractice: the messy reality

Studies of malpractice cases involving EHRs (e.g., CRICO’s malpractice data, various claims reviews) repeatedly show the same themes:

- Documentation problems are rarely the primary cause of the claim. The core issue is diagnostic error, delay in treatment, poor follow‑up, missed communication.

- When documentation does matter, it’s often because:

- Notes contradict other parts of the chart

- Critical discussions or warnings are absent

- Copy‑paste created obvious errors

- The chart doesn’t reflect the severity of illness

Not because the note “wasn’t long enough.”

One review of malpractice claims involving EHR use found that “excessive reliance on templated documentation” and “copy‑paste inaccuracies” were commonly cited in adverse outcomes. Defense attorneys in those cases didn’t argue, “But look, the note is 3,000 words.” They had to scramble to explain the contradictions.

Time in the chart does not equal safety

We also know that physicians now spend obscene amounts of time in the EHR.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Direct Patient Care | 6 |

| EHR Work | 5.5 |

Post‑residency attendings in many specialties spend 4–6 hours a day in the EHR. That includes documentation, inbox, ordering, messaging.

If the “more doc protects you” myth were true, we’d expect malpractice risk to fall as documentation expanded. It hasn’t. High‑risk specialties remain high‑risk. What’s changed is burnout, not immunity.

How Over‑Documentation Actually Hurts You

Here’s where the myth gets dangerous for post‑residency clinicians trying to survive the job market and RVU quotas.

1. Bloated notes hide the important stuff

Long, templated notes make it harder—for everyone—to see what mattered. That includes future you, the on‑call partner, and yes, the jury.

I’ve reviewed charts where the actual reason for a risky choice (“patient refused admission, understands risk of stroke”) is buried in paragraph 13 of a cloned note block. Or not there at all because the doc was too busy clicking through macros.

In court, an opposing attorney will calmly point out:

- There’s no clear statement of the conversation.

- No indication the patient understood the risk.

- No documentation of why you deviated from guidelines.

If your reasoning is buried in fluff, functionally it’s absent.

2. Inconsistencies are almost guaranteed

The longer and more templated your notes, the higher the chance that something contradicts reality: a wrong system, an impossible exam, a missed update.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Copy-paste errors | 35 |

| Conflicting notes | 30 |

| Missing key reasoning | 25 |

| Technical EHR errors | 10 |

Every inconsistency is leverage for the plaintiff. They don’t need to prove fraud. They just need to show you were careless, inattentive, or unreliable.

A short, focused, accurate note with one clear line explaining your thought process is safer than a template stuffed with nonsense that contradicts itself.

3. It makes you look defensive

Juries are human. They know what “normal” looks like after they’ve seen multiple charts during a trial.

When one clinician’s note suddenly switches from their usual two paragraphs to a dense, meticulous, multi‑page essay right after a complication, it doesn’t scream “professionalism.” It screams “oh, they knew they might get sued.”

That does not help.

Courts tend to trust documentation that looks contemporaneous, routine, and proportional to the encounter. Not five times longer when something went wrong.

4. It steals time from the thing that actually reduces lawsuits: good care and communication

Malpractice research is annoyingly consistent on one point: patients are more likely to sue when they feel ignored, dismissed, or disrespected—not simply when a bad outcome occurs.

You know what eats into time for actual conversation? Clicking through 70 boxes of ROS to “cover yourself.”

You’d be far safer, legally and clinically, if you cut your ROS from 12 systems to 4 relevant ones and used the extra 2 minutes to sit down, explain your thinking, and ask, “What’s your biggest concern right now?”

I’ve watched plaintiffs on the stand say: “No one ever explained anything to me. I felt like a number.” Then we pull the chart and see 1,500 words per day of documentation. The problem wasn’t too little typing.

What Actually Helps You Legally (That Your EHR Won’t Tell You)

Let me be clear: I’m not arguing for minimalist, cryptic charting. I’m arguing against mindless maximalism that pretends to be “defensive.”

Focus on the three things courts care about

When I talk to risk management folks who actually sit in depositions, they keep coming back to three documentation priorities:

Clarity of clinical story.

What was going on, what changed, what you thought it was, what you ruled out. Not a long ROS. A clear narrative.Decision points and rationale.

Why you did or didn’t do X. Why you discharged instead of admitted. Why you chose one antibiotic over another. One or two lines can be enough if they’re specific.Communication and informed choice.

That you discussed risks, alternatives, and follow‑up. That the patient (or surrogate) understood and agreed. Not a generic “risks and benefits discussed.” Something real.

| Note Style | Legal Impact Tendency |

|---|---|

| Short, clear, reasoned | Often supports defense |

| Long, templated, generic | Neutral to harmful |

| Inconsistent, copied | Strongly harmful |

| Sparse, no reasoning | Mild to moderately harmful |

Notice how “long” by itself doesn’t land in the “helpful” column.

Document the abnormal, not every normal

Trainees are conditioned to list every normal finding. Courts, however, care much more about what was abnormal and what you did in response.

A reasonable pattern for many encounters:

- Relevant positives and key negatives for the presenting problem

- Focused exam findings that materially affect your thinking

- The abnormal data and how you interpreted it

- The risk conversation and follow‑up plan

That’s it. Not an entire census‑level ROS in a patient with an ankle sprain.

Post‑Residency Reality: Job Market, Productivity, And Legal Fear

You’re out of training. You’re dealing with RVUs, throughput, and admin dashboards that track “documentation completeness” more than “clarity of reasoning.”

And you’re hearing two conflicting pressures:

- From admin/EHR: “Fill all the fields, complete all the checkboxes, maximize coding.”

- From your own risk anxiety: “Write more so I don’t get sued.”

This combination is brutal. But it’s also a trap.

The EHR is optimized for billing and data extraction, not for your legal protection. The more you let “max capture” drive your note, the more garbage goes into the record that lawyers can pick apart later.

One of the smartest attendings I’ve watched in court had a simple approach in practice:

- He used templates, but aggressively edited them down

- He wrote short assessments that always included a line on alternatives considered

- He specifically documented conversations when risk was non‑trivial (“discussed small but real risk of PE, patient understands signs that require immediate ED return”)

- He refused to document exams he clearly couldn’t have done thoroughly in a 7‑minute visit

When his case hit trial, his notes looked consistent, plausible, and non‑defensive. The jury believed him.

You don’t get that by writing more. You get that by writing smarter and ignoring the myth that longer = safer.

Two Visuals To Drive It Home

Watch how the “more is safer” narrative actually plays out.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Short but reasoned | 10 |

| Moderate and focused | 20 |

| Long templated | 60 |

| Long inconsistent | 80 |

The risk shoots up not when notes are short, but when they’re long and templated/inconsistent.

And think about where your time is going.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Clinical Day |

| Step 2 | Direct Patient Contact |

| Step 3 | EHR Documentation |

| Step 4 | Team Communication |

| Step 5 | Meaningful Reasoning |

| Step 6 | Template Padding |

Most clinicians would admit F is getting too big. Legally, that’s dead weight.

What You Should Do Instead Of “Write More”

One more quick reality check: you will not remember the details of today’s patient in 3 years. The chart is all you’ve got. But that does not mean you need to build a novel.

Do this instead:

- Cut autopopulated nonsense, especially impossible ROS/exams.

- Make sure your note tells a coherent story of what you thought and why.

- Flag decision points and document risk discussions in real, specific language.

- Ensure your documentation is consistent across the chart—orders, vitals, nursing notes, consults.

- Ignore anyone who tells you “more words = safer.” They’re practicing 1990s medicine in a 2026 legal environment.

And if you’re in a position to influence policy (CMIOs, medical directors), stop rewarding word count. Start rewarding clarity and consistency. Your future defense attorneys will thank you.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | New Detail |

| Step 2 | Document clearly |

| Step 3 | Keep but minimize |

| Step 4 | Leave it out |

| Step 5 | Affects diagnosis or risk? |

| Step 6 | Required for billing or regulation? |

Bottom Line

- More documentation does not automatically protect you legally; clear, consistent, focused documentation does.

- Long, templated, and inconsistent notes are routinely used against clinicians in court to undermine credibility and highlight care gaps.

- You’re safer spending time on sound decisions, real conversations, and concise reasoning in the chart than on stuffing notes with autopopulated fluff “just in case.”