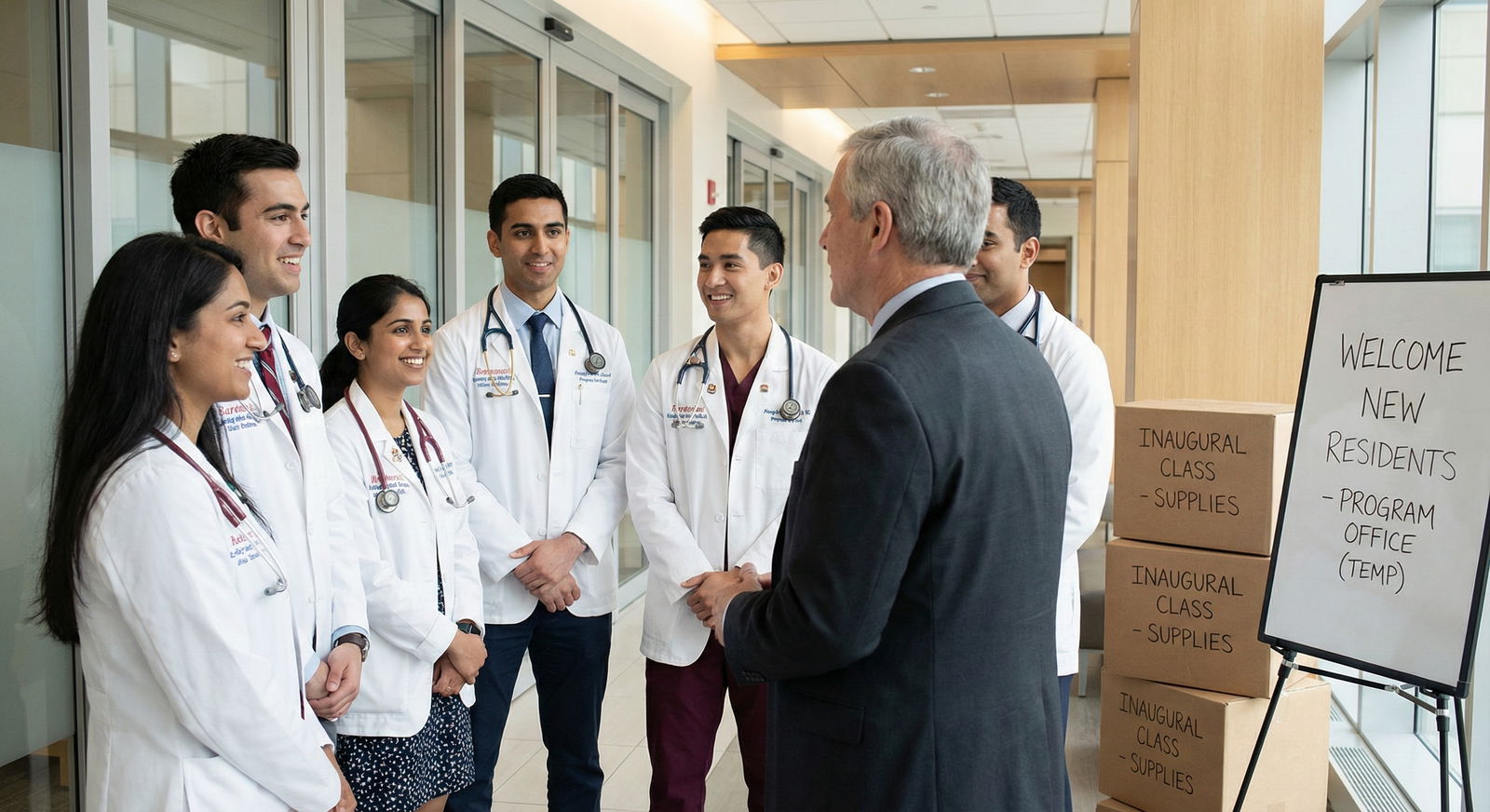

It’s March. You just matched. You scroll through your email and see the words: “We are excited to welcome you as part of our inaugural class.” Your stomach drops a little. You knew it was a newer program, but now it hits you: there are no upper levels; this thing barely exists.

On paper, the brochure looked clean. “Innovative curriculum.” “Strong mentorship.” “Growing hospital system.” You saw smiling stock photos, some vague “affiliation” with a big name academic center 3 states away, and a couple of faculty bios padded with “interests” instead of accomplishments.

Let me tell you what actually happens inside a brand-new residency. The parts the PD will not say on interview day, and certainly not in a glossy PDF.

You’re not joining a program. You’re building one. Whether you want to or not.

What “Brand-New Program” Really Means Behind Closed Doors

When a program director says, “We’re a new program,” they can mean three very different beasts:

- A totally new hospital starting GME from scratch.

- A community hospital “upgrading” from interns-only / transitional year to full categorical.

- A previously closed or on-probation program being “re-launched” under a new ACGME ID and a rebranded name.

On interview day, they’ll emphasize the first two, never the third. In the faculty workroom, though, I’ve heard the actual language:

- “We got shut down three years ago and had to rebuild everything.”

- “We inherited a mess; we’re trying to convince applicants this is ‘new.’”

- “We’ll figure it out as we go. The residents will tell us what works.”

You will not see that in the brochure.

Here’s the first uncomfortable truth: the ACGME stamp gives them the legal right to train you. It does not guarantee they’re ready to do it well. Many are building the airplane while it’s already in the air.

The “Curriculum” Is Often Just A PDF and Some Hope

On paper, every new program has a “robust curriculum.” There’s usually a detailed grid of rotations and didactics. It looks impressive.

Inside, what you really have is a speculative schedule the coordinator made to satisfy the ACGME application, plus a bunch of promises.

I’ve sat in start-up meetings where the “curriculum design” looked like this:

- PD opens ACGME requirements.

- Someone pulls up a big-name program’s schedule from their website.

- They copy the skeleton: wards, ICU, electives, clinic.

- They reverse-engineer it into a pretty table for the application.

- Then they spend the next 3 years trying (and often failing) to make reality match that table.

You know what gets left out of the marketing?

- No existing conference culture. Noon conference might be “attending reads a PowerPoint from 2014 off their desktop.”

- Simulation? Often “We’re purchasing a sim mannequin” = nothing for your first 1–2 years.

- Research time? Might be code for “You can have time off the schedule if you find your own mentor and project. We don’t actually have infrastructure.”

So when you see phrases like “innovative curriculum” and “protected didactic time,” translate them. They often mean: “We promised the ACGME we’ll do this. We’re not actually doing it yet.”

Attendings Are Learning to Be Faculty While You’re Learning to Be a Doctor

The hardest thing people underestimate: younger programs often have attendings who’ve never really taught residents before. Or they’ve only had off-service rotators, not their own full 3-year (or 4–5 year) pipeline.

They might be excellent clinicians. They might be horrible teachers. Nobody knows yet.

Behind the scenes, this is what faculty say once the door is closed:

- “I’ve never staffed an intern before; how hands-off can I be?”

- “If I let them do the procedure and something happens, am I screwed?”

- “What exactly is the expected autonomy for a PGY-1 here?”

There’s no culture yet. That has pros and cons:

Pros you actually feel:

- Less rigid hierarchy. You can sometimes negotiate responsibilities.

- Some attendings are energized and over-invested. They’ll advocate hard for you because you are “their first class.”

Cons nobody warns you about:

- Wild variability. One attending basically treats you as a fellow; the next micromanages vitals and rewrites every note.

- Cluelessness about duty hours and workload. Without senior residents running interference, everything funnels straight down to you.

I’ve seen interns essentially act as PGY-2s because there was no buffer. Admit to a busy medicine service on July 1, cross-cover 40 patients, get called for everything because there is literally no one above you. The PD calls it “early leadership responsibility.” The residents call it “trial by fire and we barely survived.”

“We’re Small and Close-Knit” Often Means “You’re Covering a Lot of Holes”

PDs love selling “small program, family feel.” In brand-new programs, that line is almost automatic.

Translation in real life: the service doesn’t run without you. There’s no depth chart.

If a PGY-2 calls out sick? PDs and chiefs in older programs start shuffling. They borrow a resident from another team, pull in a night float, or compress services.

In a new program, there is no extra resident. The solution is often:

- You work more.

- Your “elective” turns into coverage.

- Your “golden weekend” evaporates because “we just don’t have anyone else.”

Here’s how coverage actually gets discussed in a new program meeting when the residents aren’t there:

- “We can’t violate ACGME hours, but we have nobody else. Can we move their day off?”

- “They’re on elective; it’s fine if they cover nights.”

- “We’ll give them a pager-free day later.” (That “later” never comes.)

This is why new programs so often skirt the edge of duty hour violations their first year or two. Not from malice. From math. They built a schedule that assumes nobody gets sick, nobody quits, census is “average,” and the hospital does not suddenly decide to open a new service.

Moonlighting, Autonomy, and the Hidden Liability Problem

New programs love to advertise autonomy. You’ll hear: “You won’t be one of 40 residents. You’ll get hands-on experience.”

Some places mean it. You get to place lines, run codes, make decisions.

Other places mean: “We don’t have enough staff.” That’s different.

Behind the scenes, hospital leadership and risk management are nervous about one thing: liability. They know they put a brand-new resident workforce into a hospital that never had them. So they swing between two extremes:

- Hyper-conservative: every order cosigned, endless double-checking, residents feel like scribes with stethoscopes.

- Reckless: you’re covering a service that used to have two NPs and an attending, and now you’re it overnight, with a “call me if you need me” attending at home.

They never put this in writing. They definitely don’t say it in the brochure. But you feel it on night float when you’re the only physician physically in-house for three units and a rapid response is happening on the floor while a fresh ICU admit rolls in.

Shiny “Affiliations” That Don’t Do What You Think They Do

New programs often slap a line on the website like: “Affiliated with Big Name University School of Medicine.”

The reality behind that phrase can range from:

- Fully integrated academic relationship with shared faculty and conferences. to

- One guy once trained there and now we put their logo on a slide.

I’ve been in those backroom calls where the “affiliation” is negotiated:

- “Can we send 1–2 residents per year for an away elective if we sign this agreement?”

- “We’ll list you on our website under ‘clinical partners’ and you can send us a guest lecturer once a year.”

Affiliation rarely means:

- You can easily get a research mentor from that institution.

- You’ll have a realistic shot at that university’s fellowships automatically.

- Their brand name will fully rub off on you.

Sometimes they will help. Sometimes it’s essentially marketing decoration. The PD knows that “Affiliated with [National Name]” looks powerful to applicants who don’t ask follow-up questions.

The real question you should ask (and almost never do) is:

“How many of your residents have actually done rotations, research, or matched into fellowships at that ‘affiliate’ so far?” For a new program, the answer is usually zero or “we hope to in the future.”

Fellowship and Jobs: The Thing Everyone Whispers About

Residents in brand-new programs are always thinking the same thing:

“Will fellowship directors take us seriously?”

Here’s what faculty say behind closed doors when a CV from a brand-new program hits their desk:

- “I have no idea what this program is.”

- “Who do I know there? Anyone I can call?”

- “No historical data. No idea how rigorous their training is.”

So they look for anchors:

- Your Step 2 score.

- Your letters (and whether they recognize any names).

- Your research.

- Whether the hospital name, even if the program is new, is known clinically.

New programs can produce fantastic fellows. I’ve seen brand-new community programs where the first class sent people to solid cards, GI, and critical care spots. But it didn’t happen by accident. And it didn’t happen because of the logo.

It happened because:

- The PD had connections and personally called people.

- The residents hustled for research and away electives.

- They performed well on audition rotations and away electives, impressing people face-to-face.

Quiet reality: your program’s reputation lags you by about 3–5 years. You are the trial balloon for fellowship directors. Your interviews will include questions older programs never see:

- “I’m not familiar with your program. How would you compare your training volume to larger centers?”

- “What sort of procedural experience have you actually had?”

- “What percent of your graduates go into fellowship?” (You are literally the first data point.)

This is why being in the inaugural or early classes is such a strange position: you’re not just a resident. You’re part of the program’s marketing experiment to the outside world.

The Real Growing Pains: Systems, EMR, and Pure Chaos

New programs fight system problems that have nothing to do with your intelligence or work ethic.

Nobody advertises this, but here’s what actually breaks your life in a brand-new program’s first years:

- EMR chaos: Order sets, note templates, admission workflows—none of them are tuned for residents yet. You’ll discover that the “resident” login doesn’t have access to half the things you need. Fixing that takes months of IT tickets and politics.

- Page and call routing: Administrators are still figuring out who should be called for what. For a while, that person is often “whoever the resident on call is.”

You become the default problem-solver for dietary issues, transport delays, and pharmacy questions, not just medicine. - Ancillary staff adapting: Nurses who’ve only worked with attendings and NPs may not trust you at first. They’ll page the attending for things they should be asking you, or worse, they’ll ignore you and ask the hospitalist because “we always call them.”

I’ve watched interns spend 30 minutes just trying to figure out how to order a basic CT scan because radiology had no idea there were now residents, and the old policy required an attending to call every time.

You don’t read about that on the website. But it eats your time, your energy, and your sleep.

What PDs Actually Worry About (And How It Affects You)

You’re worried about training quality and fellowship.

Your PD is worried about one thing above all: keeping accreditation.

Here’s what they obsess over in meetings you don’t attend:

- Duty hour compliance.

- ACGME survey results.

- Milestones documentation.

- Faculty development boxes being checked.

If too many residents are miserable, if surveys tank, if clinical supervision is spotty, ACGME starts sniffing around. Site visits, letters, warnings.

So in those private meetings, your PD might say:

- “We need to increase didactic hours. The survey comments said teaching was weak.”

- “We can’t keep having people work 90 hours just because census is high. We’ll get reported.”

- “We must show scholarly activity. Someone get these residents on a poster.”

You are both trainee and metric. That’s the uncomfortable truth. Your evals, your survey responses, your complaints—they’re not just feedback. They’re potential regulatory landmines.

Good PDs listen and change things. Bad ones try to control the narrative and silence dissent. And in a new program, that tension is magnified because the first few years of data can make or break them.

Red Flags Hidden in Plain Sight

Let me condense the stuff nobody spells out, the patterns I’ve seen again and again in young programs.

Here’s a quick comparison of what they say vs. what it often means:

| Brochure Phrase | Likely Reality |

|---|---|

| Inaugural class | No track record, you are the experiment |

| Innovative curriculum | Unproven schedule still being built |

| Strong community affiliation | Mostly service work with limited academics |

| Affiliated with Big Name University | Loose relationship, few real opportunities |

| Early leadership opportunities | You will cover gaps with little backup |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Duty Hours Stress | 80 |

| Schedule Instability | 70 |

| Teaching Quality Gaps | 60 |

| System/EMR Hassles | 75 |

| Fellowship Anxiety | 85 |

Percentages here aren’t from a randomized trial; they’re from a decade of hallway conversations, exit interviews, and “off the record” talks with residents and faculty building these places from scratch. Those five issues show up almost every time.

When a Brand-New Program Is Actually a Good Bet

Here’s the twist: I’m not saying new programs are all bad. Some are excellent opportunities—if the context is right.

There are a few patterns where I’ve seen new programs truly deliver:

- The hospital is already a busy, respected clinical center that simply never had residents before. The volume is there; they’re just formalizing training.

- The PD has previous PD or APD experience at a real program and brought along seasoned faculty. Not a random hospitalist promoted because “we need a PD.”

- There are solid existing fellowships or subspecialty services at the same institution. That builds a floor for academic credibility.

In those setups, being in an early class can be powerful. You get visibility. Faculty actually know your name. You can shape policies. You get “founding class” status on your CV, which some fellowship directors secretly find interesting because it suggests grit and flexibility.

But you need to be honest with yourself:

You are trading a known quantity (older, established program with a track record) for higher variance. Potentially higher upside, but definitely more risk and more chaos.

What This Means for You, Day to Day

Let me strip this down to what you’ll actually feel at 2 a.m. as an intern in a brand-new program:

You will sometimes feel over-responsible and under-guided.

You will sometimes be the first person to ever ask, “What is our policy for X?” because there isn’t one yet.

You will be both learner and system designer.

You’ll help write the handoff templates, the intake forms, the cross-cover guides.

You’ll create the cheat sheets the next classes will use.

Your feedback—if your PD is not defensive—will literally shape rotations.

And yes, you’ll pay for that with more frustration up front.

But if you understand what you’re stepping into, you can use it:

- You can demand structure early: clear expectations, backup plans, and supervision norms.

- You can lean on the PD’s fear of ACGME to push for safer schedules and better teaching.

- You can over-document your experiences and outcomes for future fellowship applications, because nobody “knows” your program yet.

You’re not powerless. But you are not walking into a finished product either. You’re walking into a construction site that just barely passed inspection.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Match to New Program |

| Step 2 | Discover System Gaps |

| Step 3 | Co-create Policies |

| Step 4 | Work Around Problems |

| Step 5 | Program Reputation Improves |

| Step 6 | Burnout Risk and Exit Plans |

| Step 7 | Better Fellowships for Later Classes |

| Step 8 | PD Responsive? |

FAQ – The Questions You’re Afraid to Ask Out Loud

1. Will matching at a brand-new residency hurt my fellowship chances?

It can, but it does not have to. The lack of name recognition means you won’t get “free points” from the program’s reputation. People will judge you more on your individual record: Step 2, letters, research, performance on away rotations, and how convincingly you describe your training in interviews.

If your PD is experienced and connected, and you hustle for projects and mentors, you can absolutely land competitive fellowships. Residents from new programs match into strong spots every cycle. But if you plan to coast and let the program’s logo carry you, you picked the wrong environment. There is no logo halo yet.

2. How can I tell if a new program is actually solid or just smoke and mirrors?

Three things I always look at:

- Who is the PD and where did they train / work / lead before? Prior PD or APD experience at a real program is a big plus.

- What is the hospital’s existing ecosystem? Do they already have fellowships, strong subspecialty divisions, and a high clinical volume? Or are they trying to build everything at once?

- How specific were they on interview day? Vague answers about “future plans” for didactics, research, and affiliations are red flags. Concrete details about existing conferences, identified mentors, and defined schedules are better.

If they can’t give you at least a couple of real, named attending mentors doing ongoing research, and at least describe a functional call schedule already in place, you should be suspicious.

3. I already matched into a brand-new program. What’s the single most important thing I should do as an incoming intern?

Day one, start collecting receipts. Not in a paranoid way—strategic. Save examples of your clinical volume, procedures, QI involvement, teaching roles. Keep a running log or portfolio. You are building your own narrative and your program’s at the same time.

Then, establish a real relationship with your PD and at least one subspecialist who gets things done. You want two things from them: honest feedback on where your training is strong or weak, and advocacy when it’s time to apply for jobs or fellowship. In a new program, the right attending’s phone call matters more than the program name on your badge.

Key points:

Brand-new residencies are not finished products; they’re construction zones, and you’re part of the build.

ACGME approval guarantees minimum standards, not quality, culture, or stability.

If you understand the trade-offs and push intelligently, you can turn the chaos into leverage instead of letting it chew you up.