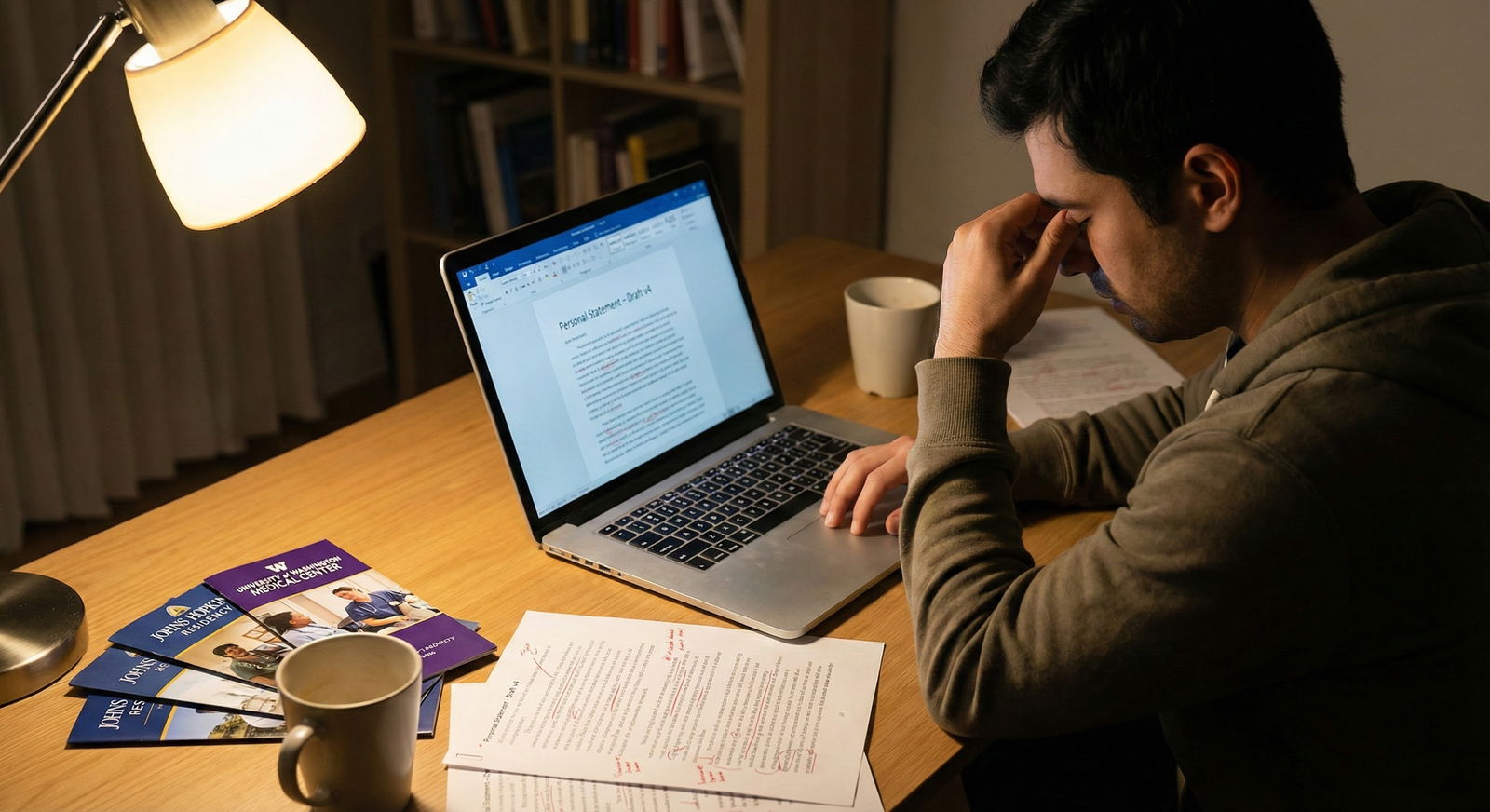

You’ve just finished your personal statement. It’s 1:37 a.m., the ERAS clock is ticking, and you’re telling yourself, “It’s fine, the content is good. Nobody cares about a few typos.”

Stop right there.

Because on the other side of that upload button is a PD who has already read 80 personal statements today, half of them interchangeable, and they’re looking for one thing to disqualify you fast: signs of a careless resident in the making. And nothing screams “careless” like sloppy grammar, typos, and formatting that looks like you copy‑pasted your way through medical school.

Let’s walk through the mistakes that brand you as careless—and how to avoid them before your statement hits a program director’s screen.

1. The “I’m Too Busy to Proofread” Error

This is the classic self-sabotage move:

- You write the statement in a rush.

- You edit it in your head while skimming.

- You upload and walk away.

On your end, it feels efficient. On their end, it reads like:

- “I was the chief of my collge’s pre-med club…”

- “During my rotation in the emerency department…”

- “I am very passionate about internal medicne.”

You think they’ll overlook it because your Step 2 score is strong or your letters are great. Many will not. I’ve seen PDs literally say, “If they can’t spell ‘medicine,’ they can’t sign my orders.”

What this signals:

- You do not double-check your work.

- You overestimate your accuracy.

- You don’t respect their time.

That’s exactly the resident who forgets to recheck a potassium, mis-types a dose, or discharges the wrong patient. And yes, they connect those dots.

How to avoid it:

- Never submit the same day you draft. Let it sit overnight. Minimum.

- Print it once. Yes, on actual paper. You’ll catch different errors off-screen.

- Do one read just for typos. Not content. Not structure. Typos only.

If you’re telling yourself “I don’t have time for that,” what they’re hearing is “I won’t have time to be safe.”

2. Sloppy Grammar That Kills Your Credibility

You don’t need to be an English professor. But the basics? Non-negotiable. Certain grammar errors immediately downgrade you from “future colleague” to “risk.”

Here are the repeat offenders that program directors notice:

A. Subject–Verb Disagreement

Examples I’ve seen in actual drafts:

- “One of the reasons I choose internal medicine are the variety of cases.”

- “The skills I developed during my rotations has prepared me well.”

This is third-grade grammar. When a PD sees it, it reads as laziness, not ignorance.

Fix it:

- Sing it in your head. “One of the reasons is…” not “are.”

- “Skills… have prepared me” (plural + plural).

If you can recall the difference between cefazolin and ceftriaxone, you can remember subject–verb agreement.

B. Tense Shifts That Make Your Story Sloppy

Personal statements love the whiplash:

- “I was working in the ICU when a patient codes and I run to the bedside.”

Pick a lane. Past or present. Mixing them randomly makes you look unfocused.

Use:

- Past tense for prior experiences: “I worked, I learned, I decided.”

- Present tense only for broad truths: “I am drawn to…”, “I am excited to pursue…”

C. Fragment Overload

Occasional intentional fragments for emphasis? Fine.

Half your statement as choppy fragments? Amateur hour.

Bad:

- “In the ICU. At 3 a.m. Completely overwhelmed. But learning.”

You’re not writing spoken-word poetry. You’re trying to convince someone you can write orders that make sense.

Fix by turning at least 90% of those into complete sentences. Keep the rare fragment for real impact, not as a style crutch.

3. Typos That Instantly Cheapen You

Typos happen. But they should be rare and minor. You’re not writing a text; you’re applying for a medical license gateway.

The worst ones are not the obscure words. It’s the obvious:

- Misspelling your own specialty

- “pediatrcs”

- “anestheisa”

- Misspelling key roles or exams

- “Step 2 CK exam was a pivital experience.”

- “I served as cheif scribe.”

This makes your claim of “attention to detail” sound like a joke.

Red-flag typo zones:

- Your name

- Program or institution names

- Specialty name

- Common medical terms you should know: “hemorrhage,” “ischemia,” “diabetes,” “residency,” “attending,” “colleague”

If you get these wrong, what you’re silently saying is: “I didn’t respect this enough to run spellcheck properly.”

4. Apostrophes, Plurals, and the “Doctor’s” Disaster

There’s a special kind of pain in reading:

- “I worked with many doctor’s who inspired me.”

- “The ICU’s were busy.”

- “I love taking care of patient’s.”

These errors scream “I never learned basic written English and I also didn’t care enough to ask someone who has.”

Quick rules you absolutely must get right:

- Plural: patients, attendings, residents, physicians

- Possessive singular: patient’s history, resident’s note

- Possessive plural: patients’ families, residents’ responsibilities

- Never use an apostrophe to make a regular word plural. Ever.

If this is shaky for you, do not “hope for the best.” Ask someone who’s good with grammar to specifically look for this.

5. Formatting That Looks Like You Copy-Pasted From Your Notes App

This is where you quietly ruin an otherwise decent statement.

Sloppy formatting creates friction. The PD has to work harder to read your file. They won’t. They’ll just move on.

Common formatting sins:

- Walls of text: One 800-word paragraph. Zero breaks. Instant “nope.”

- Random spacing:

- Extra spaces between words: “I am very interested…”

- Uneven line breaks, weird wrapping

- Inconsistent paragraph style:

- First paragraph indented, others not

- Random blank lines all over the place

- Fonts & bullets:

- Using bullets or numbered lists in a personal statement (ERAS often strips formatting anyway)

- Fancy characters that don’t render correctly

Your statement should look like this:

- 3–5 paragraphs

- Clean left alignment

- No weird symbols or emojis

- One consistent spacing between sentences (one space, not two all over the place)

You want them to forget the formatting exists. The second they notice it, it’s usually because something is wrong.

6. Inconsistent Capitalization and Titles

This one’s subtle but deadly. It communicates that you don’t understand hierarchy, roles, or professional writing norms.

Bad examples:

- “I worked with Doctor Smith, who became an important mentor.”

- “In the emergency Department, I learned…”

- “I spoke with the program director of Internal Medicine at my home institution.”

- “I am excited to apply to Family medicine.”

How it should look:

- “I worked with Dr. Smith, who became an important mentor.”

- “In the emergency department, I learned…”

- “I spoke with the internal medicine program director at my home institution.”

- “I am excited to apply to family medicine.”

Basic rules:

- Capitalize: Internal Medicine Residency Program (when referring to a specific formal name), ERAS, USMLE, Step 2 CK, ICU (common abbreviations).

- Don’t capitalize generic roles or departments: attending, resident, intern, emergency department, operating room.

Sloppy capitalization makes you look like you’re guessing. Residents don’t get to guess on orders, notes, or forms.

7. “I, I, I” and Repetitive Sentence Structure

This is less about grammar and more about reading fatigue. But it still screams “careless.”

You’ve probably seen this pattern:

- “I was born in…”

- “I learned…”

- “I realized…”

- “I hope…”

- “I believe…”

Fifteen sentences in a row like that and the reader stops caring. It sounds juvenile and unedited.

Same with overused phrases:

- “I am passionate about…”

- “I have always wanted to be…”

- “I am confident that…”

Repetition signals you didn’t read your own work critically.

Quick fix pass:

- Look for repeated sentence starts (“I”, “During”, “As a”).

- Change the structure of every 2nd or 3rd sentence so it doesn’t start the same way.

- Replace cliché phrases with actual specifics.

You’re not just trying to sound good. You’re proving that you can think and write like an adult professional.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Typos | 80 |

| Grammar errors | 70 |

| Poor formatting | 60 |

| Clichés | 65 |

| Too long/short | 40 |

8. Copy-Paste Artifacts That Expose You Instantly

Program directors are not stupid. They can smell a copy-paste or AI-polished paragraph a mile away, but I’m not even talking about that.

I’m talking about technical artifacts:

- Sudden font size or style changes (in systems where this shows).

- Weird spacing before or after certain lines.

- Smart quotes and dashes turning into little boxes or question marks.

- A program name from a different specialty you forgot to remove.

Worst of all:

“I am thrilled at the possibility of training at [PROGRAM NAME].”

You meant to go back. You did not. Now you look careless and a bit dishonest.

How to avoid this:

- After you paste into ERAS, read it there. Slowly. Line by line.

- Specifically scan for bracketed text, placeholder text, or any [ALL CAPS] you used as a reminder.

- Avoid program-specific sentences in your core personal statement unless you’re truly using it just for one place.

No one wants a resident who sends the wrong note to the wrong chart. This is the same problem in a safer context.

9. Wrong Length, Wrong Signal

Length is not just about word count. It’s about judgment.

Two kinds of mistakes:

Way too short (like 300–400 words)

- Reads as: “I couldn’t be bothered.”

- Or: “I have no insight into my own experiences.”

Way too long (1000+ words of rambling)

- Reads as: “I don’t know what’s relevant.”

- Or: “I will also write 3-page progress notes on stable patients.”

Most solid residency personal statements land around 600–850 words. Enough to tell a story, not enough to become a hostage situation.

If your draft is massively outside that range, it’s not “unique.” It’s poorly edited.

10. Signal Mismatch: Claiming “Attention to Detail” While Being Sloppy

This one is brutal.

If your statement includes phrases like:

- “I have excellent attention to detail…”

- “My thoroughness is one of my greatest strengths…”

- “I pride myself on my meticulous work…”

…and that same paragraph has a typo, grammar error, or formatting issue?

You’ve just torpedoed your credibility.

Do not brag about traits your writing immediately contradicts. Either:

- Fix the writing so it actually supports the claim, or

- Stop claiming the trait explicitly and let your examples show it.

Program directors are allergic to self-descriptions that don’t match the evidence in front of them.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Draft statement |

| Step 2 | Wait 24 hours |

| Step 3 | Print and mark typos |

| Step 4 | Revise in doc |

| Step 5 | Read aloud once |

| Step 6 | Have 1-2 people review |

| Step 7 | Paste into ERAS |

| Step 8 | Final on-platform read |

| Step 9 | Submit |

11. A Simple, No-Nonsense Checklist Before You Hit Submit

You want to avoid looking like the careless resident? Fine. Then you don’t skip this part.

Read your statement and ask:

Typos & basic grammar

- Any misspelled specialty names?

- Any “doctor’s” when you meant “doctors”?

- Any obvious subject–verb disagreements?

Formatting

- Reasonable paragraph breaks (3–5 paragraphs)?

- No random spacing, broken lines, or odd symbols?

- No bullets, tables, or weird indentation?

Consistency

- Tenses consistent within stories?

- Capitalization standard and professional?

- No bracketed or placeholder text left?

Tone & structure

- Not every sentence starts with “I”?

- No repeated phrases like “I am passionate” every other line?

- Length roughly 600–850 words?

If you blow past this checklist and upload anyway, you’re not unlucky if it hurts you. You’re just careless.

12. Who Should Not Be Your Editor (And Who Should)

Another common mistake: showing your statement to the wrong people.

Bad choices:

- The friend who “doesn’t really read much but thinks it sounds good.”

- The attending who rewrites it in their own voice and adds more jargon and buzzwords.

- Your parent who cares more about telling your life story than sounding like a resident.

You need two types of reviewers:

Content/fit person

- Someone who understands residency (senior resident, chief, faculty)

- They can tell you if it sounds appropriate, professional, and realistic

Language/clarity person

- Someone who is actually good with English and detail

- They don’t have to be medical—could be a friend who writes well, a former teacher, or a partner who catches every misplaced comma

One more thing: 5–6 reviewers is too many. You’ll end up with a Frankenstein statement. Two or three max.

| Area | Sloppy Signal | Strong Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Typos | Misspelled specialty, “doctor’s” for plural | Clean spelling in high-stakes words |

| Grammar | Tense shifts, subject–verb errors | Simple, correct, unobtrusive grammar |

| Formatting | Wall of text, weird spacing | 3–5 balanced paragraphs, consistent spacing |

| Consistency | Random caps, mixed style | Standard capitalization, steady voice |

| Length & Focus | 300 words or 1200+ ramble | ~600–850 words, focused and coherent |

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Will one or two small typos really ruin my chances?

One tiny typo in an otherwise clean, strong statement probably won’t kill you. But patterns do. Three, four, five obvious errors—especially in basic words—create a clear impression: this person doesn’t review their work. In a competitive pile, that’s enough to push you below someone who looks equally good on paper but more careful in writing.

2. Can I use Grammarly or AI tools to fix my grammar and typos?

You can use them as a first pass, not as your only editor. These tools miss nuance, sometimes introduce awkward phrasing, and can make your writing sound generic if you let them rewrite whole sections. Use them to catch obvious issues, then read the result out loud and have a human you trust look it over. If it stops sounding like you, you’ve gone too far.

3. My English isn’t perfect—will programs hold that against me?

Most programs are reasonable about language differences, especially for IMGs. But “not native” is not a free pass for carelessness. You’re still expected to produce a statement that is clear, readable, and free of distracting errors. If English is a challenge, you need more review, not less—especially from a strong writer who can help you clean it up while keeping your voice.

Key points to walk away with:

- Sloppy grammar, typos, and formatting do not read as “human.” They read as careless, which is deadly in residency.

- Most of these problems are fixable with a 24-hour pause, a printed read-through, and one or two good reviewers.

- If you’re going to claim attention to detail, your personal statement is where you prove it—or expose yourself.