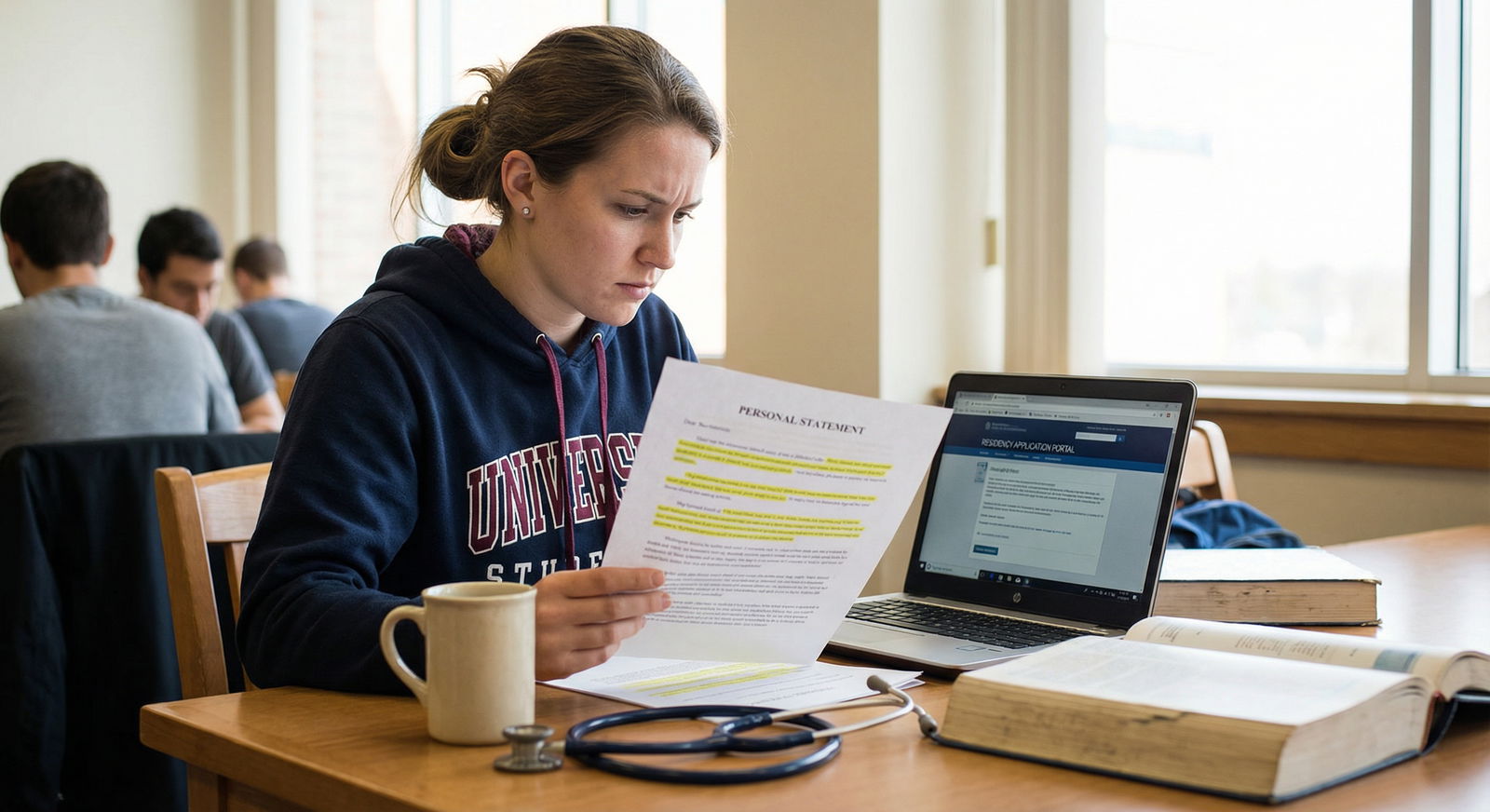

You are two weeks from ERAS opening, sitting in front of your personal statement draft. You have written 700 words. You have also said absolutely nothing unique about yourself. You have an “ever since I was a child” opening, a “compassionate, hardworking, dedicated” middle, and a “where I can grow as both a clinician and a person” ending.

If that sounds uncomfortably familiar, you are in the danger zone.

This is where strong applicants quietly tank their applications: not with typos, but with clichés that make them sound like 5,000 other people in the same specialty. I have seen excellent candidates get remembered as “the third ‘grandfather’s heart attack’ essay of the day.” You do not want to be that person.

Let me walk you through the most common personal statement clichés that instantly weaken your residency application—and how to avoid falling right into them.

The Origin-Story Trap: “Ever Since I Was a Child…”

You know this one.

“Ever since I was a child, I have wanted to be a doctor.”

Or its slightly dressed-up cousin: “My passion for medicine began when I was five years old and my grandmother was diagnosed with cancer.”

Programs see this line hundreds of times. It signals three things you do not want associated with your application:

- You are relying on generic narrative templates instead of real reflection.

- You are starting your story too early and too far from anything that matters now.

- You are spending precious space on something that cannot distinguish you.

Here is the problem: nobody cares what you allegedly thought when you were five. They care how you think now. They care how you behave on rounds, how you respond to stress, and whether you have enough insight to be coachable.

Use childhood only if:

- It connects directly to a sustained, traceable pattern (not a single dramatic event), and

- You can make a clear bridge from then to now in 1–2 sentences, not three paragraphs.

What to avoid:

- Long, cinematic childhood scenes (“The fluorescent lights buzzed as my mother clasped my hand in the emergency room…”)

- Overwrought hospital memories from the patient-side when you were very young

- Sacred origin-myth tone, as if medicine was destiny written in the stars

What to do instead:

Start closer to the present. A turning point in medical school. A clinical experience that changed how you behave as a learner, not just how you “felt.” Or a specific moment in third-year when you realized, “I want to spend my life in rooms like this, doing work like this.”

If your first sentence could be copy-pasted into 10 other personal statements in your class, delete it.

The Tragedy Template: “My X’s Illness Inspired Me to Pursue Medicine”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Family Illness | 60 |

| Childhood Dream | 45 |

| Desire to Help | 80 |

| Random Patient Story | 70 |

| Career-Changer Arc | 20 |

A family member’s illness. A grandparent’s death. Your own surgery. I am not minimizing the emotional weight of those experiences. But admissions committees are saturated with these narratives.

The mistake is not mentioning those events. The mistake is using them as the central justification for choosing your specialty or medicine itself.

Why this weakens your statement:

- It can feel emotionally manipulative when written poorly.

- It rarely shows anything about your behavior, only your feelings.

- It makes you sound like thousands of others whose primary “why medicine” is tragedy.

I have read countless versions that go like this:

- Relative gets sick.

- You feel helpless.

- You admire the doctors.

- You vow to become one.

- You jump 10 years to med school with no real intervening detail.

Nothing in that arc tells me how you work on a team, how you handle fatigue, or what you have done in real clinical spaces. It is all passive.

If you must include a personal or family illness:

Keep it brief and functional. Two to three sentences max. Then move to how that experience actually shaped concrete behavior: the way you approach serious conversations with families, how you manage uncertainty, how you tolerate seeing suffering repeatedly without burning out or numbing out.

Do not:

- Build your entire essay around “the day everything changed”

- Spend multiple paragraphs on pre-med life story instead of residency-relevant growth

- Try to wring tears out of the reader; they are mostly tired, not tearful

Let the event be context, not the plot.

The “I Just Want to Help People” Non-Reason

If the core of your motivation is “I like science and I want to help people,” you have basically said nothing. That describes every single applicant in the stack.

Residency PDs roll their eyes (internally) when they read:

- “I am passionate about helping others.”

- “I knew I wanted a career where I could help people every day.”

- “I find fulfillment in making a difference.”

Of course you do. At least I hope so. That is the entry ticket, not your unique selling point.

The mistake here is using generic altruism as your entire identity. It comes off as superficial and untested, especially if you never show a scenario where helping someone was not clean and rewarding.

How to avoid this:

Force yourself to answer: “Help people how, where, and with what kind of problems?”

Tie your motivation to specific types of:

- Clinical encounters (e.g., longitudinal management, acute resuscitation, procedural work)

- Populations (e.g., adolescents with chronic mental illness, medically complex elderly)

- Workflows (e.g., team-based inpatient medicine vs. one-on-one longitudinal outpatient care)

Your statement should sound like: “I am drawn to [specialty] because I like this kind of sick patient, in this kind of environment, doing this kind of work.” Not “I want to help people.”

The Buzzword Salad: “Compassionate, Hardworking, Dedicated…”

Adjectives are easy. Evidence is hard. Too many applicants lean on self-descriptors that no one can verify.

Common offenders:

- Compassionate

- Empathetic

- Hardworking

- Dedicated

- Resilient

- Team player

- Lifelong learner

If you have more than two of those words in your essay, you are probably diluting your impact.

Programs will believe:

What you show, not what you claim.

Instead of writing, “I am a hardworking, resilient team player,” write a short vignette where you stayed late to help a struggling intern, or stepped into an unglamorous task without being asked, or received direct feedback and changed your behavior.

Do not tell me you are teachable. Show me the time an attending told you, “You need to tighten up your presentations,” and you actually did—how you changed your pre-rounding, structured notes, or patient summaries. That is evidence.

Quick test:

Highlight every adjective that describes your character. Then highlight every specific behavior, story, or quote from a supervisor. If adjectives outnumber evidence, your essay is weak.

The Random Patient Story That Goes Nowhere

This is the classic trap:

You write a long, emotionally charged story about a patient encounter. You describe them in detail. You describe your feelings. You describe the outcome.

Then… nothing.

The statement ends with some vague line like, “This experience solidified my desire to pursue internal medicine.”

That is not enough.

The problem is not using a patient story. Those can be powerful when done right. The problem is using the patient as the main character, not you. Residency programs are trying to understand how you think and function on the team. The patient’s details are secondary.

A strong clinical vignette must answer:

- What did you actually do?

- What did you learn that changed how you behave now?

- How is that learning directly relevant to your chosen specialty?

If your story could be summarized as “I saw something sad and now I like this field,” you have wasted space. No one cares that you felt “humbled.” They care what you did on post-call day when you were exhausted and the new admission rolled in.

Keep patient stories tight:

- Set the scene in 1–2 sentences. No excessive sensory overload.

- Focus on your role, thoughts, decisions, missteps, and growth.

- End with a specific, behavioral takeaway, not a vague “I learned the importance of empathy.”

If the patient story does not illuminate how you will show up as a resident, cut it.

The Specialty Flattery Essay

This is the essay where you spend 500+ words telling programs what they already know about their field. It usually looks like this:

“Internal medicine is a field that requires critical thinking, broad knowledge, and lifelong learning. Internists are the detectives of medicine, piecing together complex puzzles…”

Or:

“Surgery is a demanding specialty that requires precision, dedication, and the ability to perform under pressure.”

Every specialty knows what it is. They do not need you to recite its brochure.

This kind of writing makes you disappear because:

- You sound like UpToDate + a motivational poster.

- You have not actually spoken about yourself.

- You seem to be trying to impress the specialty instead of connecting your lived experiences to its demands.

Your task is not to praise the field. It is to explain why you are a good match for the field’s realities—both the appealing and the unpleasant ones.

So instead of:

“Psychiatry allows for deep connection with patients and understanding of the human mind.”

Try:

“Psychiatry drew me in when I realized I was more interested in why my patients with recurrent admissions kept coming back than in tweaking their insulin doses. On my psych rotation, I saw that careful attention to trauma history and social context changed readmission patterns more than any new medication we added.”

See the difference? One is a description of the field. The other is your relationship to the work.

The “Generic Life Lessons” Conclusion

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Weak Start: Childhood Story |

| Step 2 | Generic Tragedy |

| Step 3 | Buzzword Self-Description |

| Step 4 | Flattery of Specialty |

| Step 5 | Generic Conclusion |

| Step 6 | Strong Start: Recent Clinical Moment |

| Step 7 | Your Role and Growth |

| Step 8 | Evidence of Fit for Specialty |

| Step 9 | Clear Forward-Looking Conclusion |

The last paragraph is where many otherwise good statements fall apart. You have a solid middle, and then you default to:

- “I am excited to continue growing as both a clinician and a person.”

- “I look forward to joining a program where I can develop my skills and contribute to the medical community.”

- “Ultimately, I hope to become a compassionate, knowledgeable physician who makes a difference in patients’ lives.”

This does nothing. It is verbal wallpaper.

You do not need to summarize your essay. The reader just finished reading it.

Use your conclusion to:

- Briefly restate what draws you to this specialty in concrete terms, and

- Look forward in a specific, grounded way: what kind of resident do you want to be on day-to-day level? How do you hope colleagues describe you?

Avoid:

- Aspirational fluff (“I hope to be a leader in the field.”) with no basis in your history

- Overly dramatic final lines meant to sound profound

- Repeating the words “compassion,” “passion,” “fulfilling,” or “journey” yet again

Clarity beats poetry here.

The “Laundry List of Achievements” Masquerading as a Story

Another common mistake: turning your personal statement into a narrative CV. You mention every research project, leadership role, and volunteer activity in chronological order and pretend it is a story.

Programs already have your ERAS. They have your publication list. Repeating it in prose is a waste.

Warning signs you are doing this:

- Every paragraph is built around a different experience with no thematic thread

- You keep writing “Another experience that shaped me was…”

- The essay feels like you are afraid to leave anything out

You weaken your application when you signal that you do not understand the purpose of this document. The personal statement is for depth, not breadth.

Better approach:

Pick 2–3 experiences that:

- Genuinely changed how you practice or think, and

- Relate directly to your fit for the specialty

Go deep on those. Show the before/after. What did you do incorrectly at first? What feedback did you receive? What did you change?

The reader should be able to say, “I understand how this person will behave when my senior resident is drowning on a call night,” not just “This person was very busy in med school.”

Red Flags That Make You Sound Unrealistic (Or Naive)

Some clichés are not just boring; they actively make you look unprepared for residency.

Watch for these:

- Over-romanticizing the specialty: “Every day in the OR is a privilege and a joy.” (No mention of 4 a.m. pre-rounds, difficult attendings, or complications.)

- Savior complex: “I want to be the kind of physician who always has the right answer and never gives up on a patient.” (Sounds nice; not reality.)

- Vague future plans: “I hope to one day give back to my community and advocate for my patients.” (How? Based on what pattern of behavior so far?)

- Absolute statements: “I know without a doubt that surgery is the only career that will ever fulfill me.” (PDs know half their interns will question everything in January.)

Programs want people who understand the job is hard, messy, and often unglamorous. If your essay reads like a brochure about “making a difference,” you sound like you have not been on enough 28-hour calls.

Show that you:

- Have seen some of the realities (death, medical errors, conflict on teams)

- Are not naive about the limits of what you can do

- Still choose the field with open eyes

That level of groundedness is rare and refreshing.

Common Clichés vs Strong Alternatives

| Weak Phrase / Move | Stronger Alternative Focus |

|---|---|

| “Ever since I was a child…” | Recent clinical moment showing current self |

| “I want to help people” | Specific patient problems you enjoy tackling |

| “I am compassionate and hardworking” | Story showing feedback, effort, and growth |

| Long tragic family illness narrative | Brief context + concrete professional impact |

| Specialty description and flattery | Your relationship to the work and environment |

Use this as a checklist while editing. If your draft leans heavily on the left column, you have work to do.

How to De-Cliché Your Existing Draft

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Cutting Clichés | 30 |

| Adding Specifics | 35 |

| Structuring | 20 |

| Polishing Language | 15 |

You probably already have a draft. Good. Now your job is to strip out the dead phrases and replace them with real content.

Step 1: Cliché purge

Go through your draft and highlight:

- Childhood references

- Family tragedy sections

- Any sentence that could appear in 100 other statements (especially “help people,” “make a difference,” “lifelong learner,” “compassionate,” “passionate about X”)

Cut or drastically shrink those.

Step 2: Replace with concrete scenes

For each major claim about yourself (“I work well under pressure,” “I value teamwork,” “I am drawn to continuity of care”), add:

- A 3–5 sentence example: specific rotation, your role, the challenge, and what changed in you afterward.

Step 3: Fix your opening and ending

Opening: Start with a short, clear moment closer to now—an attending’s comment, a specific call-night, a clinic pattern you noticed. No grand origin myths.

Ending: Two or three sentences that (a) clearly state what attracts you to the specialty’s concrete work, and (b) how you hope to show up as an intern. Then stop. Do not sermonize.

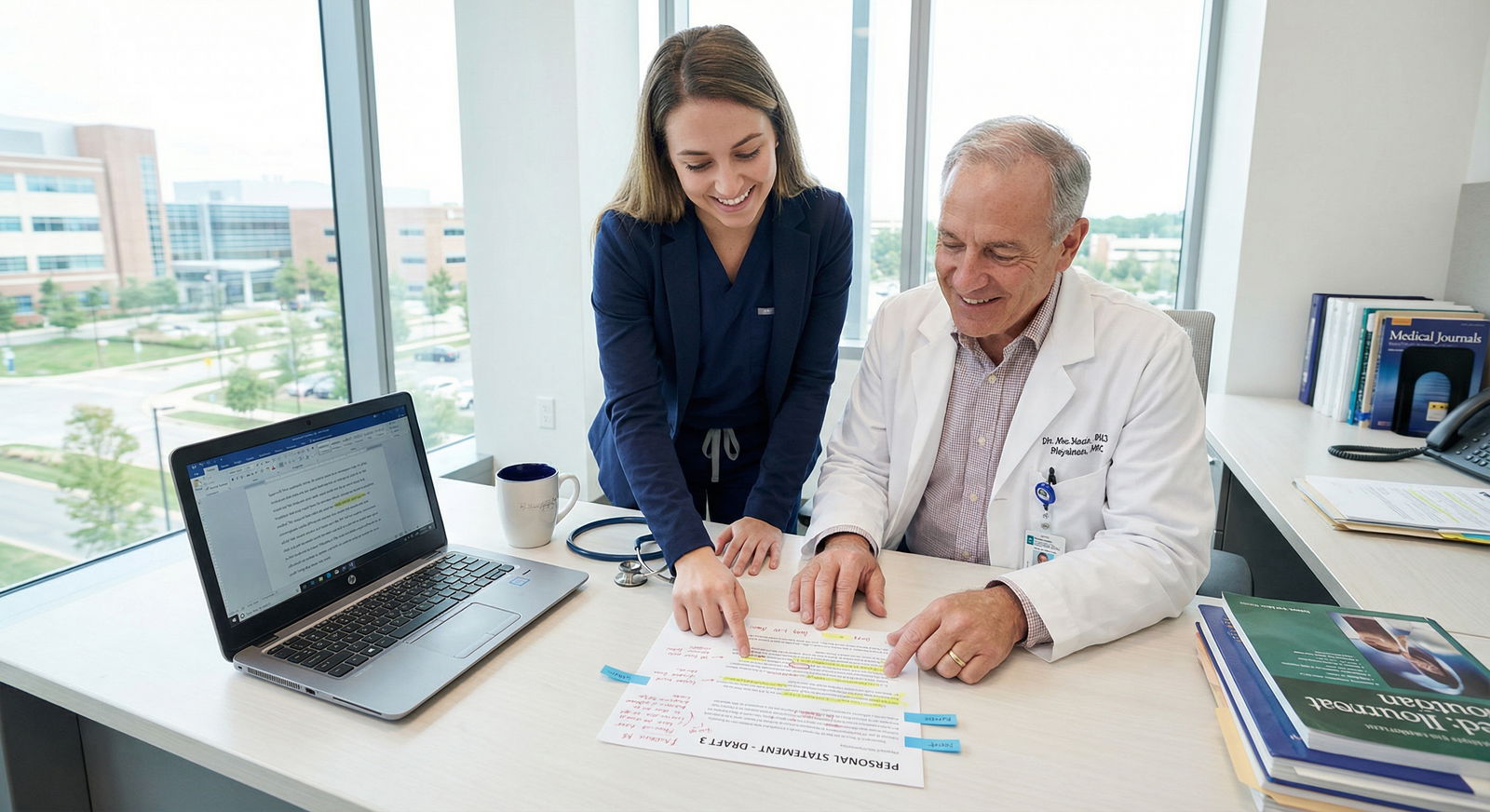

Step 4: Get specialty-aware feedback

Give it to someone in the field if you can. Ask one question only: “After reading this, do I sound like someone who understands the day-to-day reality of your specialty, or like an idealistic student still imagining it?” If they hesitate, you are not done.

Quick Self-Audit Before You Hit Submit

Before you upload your personal statement to ERAS, run a five-minute check. If you answer “yes” to several of these, you are still stuck in cliché land:

- Does your first sentence mention childhood, a vague passion, or a family member’s illness?

- Do you describe yourself with more than two generic character adjectives?

- Could your conclusion be pasted into almost any other applicant’s essay without changing a word?

- Do you spend more time describing patients than describing your own thinking and behavior?

- Do you explain what the specialty is rather than how you fit into it?

If so, you are not ready. Better to take one more night and fix it than let a bland, generic statement drag down an otherwise strong application.

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Is it always wrong to mention a family illness or childhood influence?

No. The mistake is letting those dominate your essay or serve as your sole justification for medicine or your specialty. A brief mention—2–3 sentences—can work if it sets context and you quickly move to professional experiences, your behavior, and how you function in clinical settings now. If you are spending a full paragraph or more on pre-med life, you are over-investing in material that does not help programs decide whether they want you as a resident.

2. Do program directors actually read the personal statement, or is it a formality?

They do read it, but usually quickly and selectively. Often it is scanned after your ERAS data and letters, to answer questions like: “Does this person understand the specialty? Do they seem mature? Any red flags?” A clichéd, generic statement will not usually sink you alone, but it will not help you stand out either. However, a focused, grounded, specific statement can tip you into “let’s interview this one” when you are on the margin.

3. How long should my residency personal statement be, realistically?

Most strong statements fall in the 600–750 word range. Long enough to show growth and specific examples, short enough that a tired PD does not resent you. If you need more than 800 words to say why you want this specialty and who you are as a learner, you are probably repeating yourself or padding with clichés. Aim for tight, specific, and readable over “epic life story.”

Key points to remember: Cut the clichés; they make you invisible. Replace vague virtue-signaling with specific behavior that shows who you are on the wards. And stop writing for your imaginary five-year-old self—write for the jaded PD skimming at 11:45 p.m. who needs one clear reason to remember you.