Your personal statement sounds like everyone else’s because you wrote it the way everyone is told to write it. That is the problem. And it is fixable.

I am going to walk you through how to take a generic, “I have always wanted to help people” residency personal statement and turn it into something that sounds like a real human with a real mind. Not a template.

You do not need to start over. You need to diagnose what is generic, then rebuild around specifics, structure, and voice.

Let us fix it step by step.

Step 1: Diagnose Exactly Why Your Draft Is Generic

First, you need a clear diagnosis. “It sounds bad” is not usable feedback. You need to see the patterns.

Here is the quick test: if I removed your name and specialty from your statement, could it describe 500 other applicants? If yes, you have a generic draft.

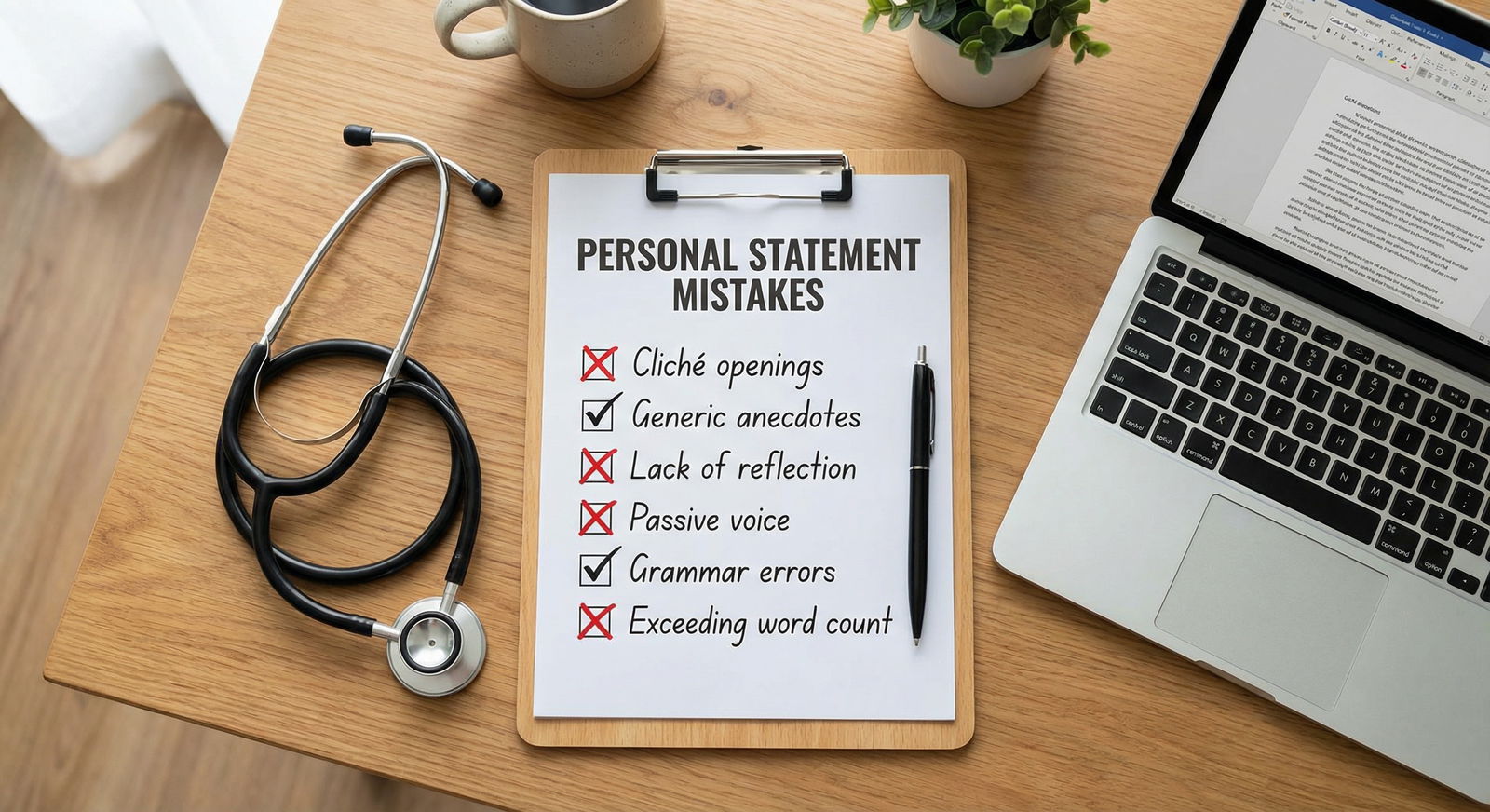

Common failure patterns I see over and over:

Template opening

- “I have always wanted to be a physician…”

- “Medicine is the perfect combination of art and science…”

- “From a young age, I knew I wanted to help people…”

- “During my third-year clerkships, I discovered my passion for [specialty]…”

Grand, vague claims with no anchor

- “I am a compassionate, hardworking team player.”

- “I am committed to lifelong learning.”

- “I will be a strong resident and asset to your program.”

Rotations list disguised as narrative

- One paragraph per rotation, each a generic summary:

- “On internal medicine, I learned the value of teamwork…”

- “On surgery, I learned the importance of attention to detail…”

- “On pediatrics, I learned how to communicate with families…”

- One paragraph per rotation, each a generic summary:

Cliché “growth” arc

- Early struggle → mentor said something inspiring → now you are “more confident and ready for residency.”

- No concrete before/after. Just vibes.

Boilerplate closing

- “In conclusion, I am excited for the challenges of residency.”

- “I am confident that my experiences have prepared me well.”

- “Thank you for considering my application.”

You probably recognized several of these in your own draft.

Here is what I want you to do right now:

- Print your statement or open it on screen.

- Take a highlighter and:

- Highlight any sentence that could appear in 200 other personal statements word-for-word.

- Underline any sentence that is only true because of you (your specific patient, story, decision, fear, or preference).

If what is highlighted dwarfs what is underlined, that is your core problem. You are writing to sound correct, not to sound like you.

We will fix it by doing three things:

- Strip out generic filler.

- Insert specific, concrete details.

- Rebuild the structure around 1–2 meaningful stories + clear, adult reasoning about why this specialty and what you offer.

Step 2: Strip Out the “Residency Brochure” Language

You cannot revise around fluff. You have to cut it.

Here is the rule: If a reasonable, non-awkward person in your class could say the same sentence about themselves, it is probably useless.

Examples of sentences that need to go:

- “I am passionate about patient care.”

- “I look forward to collaborating with an interdisciplinary team.”

- “I respect the diverse backgrounds of my patients.”

- “I am interested in both inpatient and outpatient medicine.”

- “I am excited to continue learning and growing.”

These are not bad things. They are just not differentiating things. PDs assume all of that. They learn nothing new about you.

Go through your draft and delete:

- All “I am passionate…”

- All “I look forward to…”

- All “I am excited for the opportunity…”

- All restatements of your CV (“I studied biology and did research…”) unless you add something that is not on the CV (what it did to your thinking, what it changed in how you approach patients).

You should feel slightly panicked after this pass. The draft will get shorter. Good. That gives you room for content that actually matters.

Step 3: Replace Abstract Claims With Concrete Evidence

You cannot say yourself into being impressive. You have to show people the evidence and let them infer.

Bad:

“I am a strong communicator and advocate for my patients.”

Better:

“When our team considered discharging a patient with brittle diabetes who kept missing appointments, I realized every call reminder was being made during her night shift. I asked if we could switch to mid-day calls for a week. She showed up to each visit.”

Notice a few things:

- Same trait (advocacy, communication), but now it is a vivid moment.

- Shows how you think, not just how you label yourself.

- No bragging adjectives needed.

Take each of your vague “I am” statements and force them through this conversion:

List your 3–5 main claims in the margin:

- “I am thorough.”

- “I handle stress well.”

- “I value teaching.”

- “I care about underserved patients.”

For each, answer brutally:

- What is one specific moment where I actually did this in real life?

- What did I notice that others missed?

- What decision did I make that a more passive student would not have made?

Turn that into 3–5 sentences of story.

Example of conversion:

- Claim: “I handle stress well.”

- Moment: Code at 3 a.m. on MICU where half the team was new, nurse looked to you because you had been on the service two weeks, you grabbed the ABG kit, started compressions, or quietly handled all family updates.

- Write:

- What you were thinking before.

- One detail that captures the chaos (alarm tones, sweat, someone dropping an instrument).

- The one thing you decided to do that helped.

Do this for 2–3 traits, not ten. Depth beats breadth.

Step 4: Rebuild Around One or Two Anchoring Stories

Strong personal statements are built around a small number of well-chosen stories, not a scrapbook of everything you ever did.

You need 1–2 anchor stories that do most of the work. The rest is framing.

Criteria for a good anchor story:

- It changed how you think or what you want from this specialty. Not just “memorable patient.”

- It shows you practicing some core habits your specialty values:

- IM: curiosity, following threads, longitudinal thinking, patience with complexity.

- Surgery: decisiveness, manual discipline, comfort with hierarchy and acute stress.

- Pediatrics: communication at multiple levels, coaching families.

- Psych: patient listening, tolerating ambiguity, sitting with uncomfortable emotions.

- It reveals something about you that is not in your CV bullets:

- A weakness you faced and worked on.

- A preference (you like the quiet 20 minutes after a code where notes get done and the team recalibrates).

- A specific type of patient or problem that keeps your brain engaged.

Do not pick:

- The patient everyone uses (trauma bay polytrauma, first code blue, “child with cancer who taught me resilience”) unless you can tell it in a way that is extremely specific to your experience.

- A story where you were basically an observer and the attending did everything.

You were a med student. Obviously you were not saving the world. That is fine. What matters is what was happening in your head and what you actually did do.

Structure template that works

A simple, effective structure:

Hook paragraph (story fragment)

- Drop us into a moment with sensory detail.

- 4–7 sentences. No specialty sales pitch yet.

Reflection + connection to specialty

- What did that moment show you about the work itself?

- How did it pull you into this field specifically?

Short “supporting evidence” paragraph

- 1–2 other experiences that reinforce the same theme.

- Lab, QI, teaching, other rotation. No laundry list.

What you are like on the team

- Concrete behaviors, not adjectives.

- “I am the person who…” + a specific example.

Forward-looking close

- What kind of training environment you are seeking.

- What you want to get better at.

- One line that sounds like an actual human wrote it.

That is it. You do not need a five-act hero’s journey.

Step 5: Rewrite the Opening So It Does Not Sound Like a Brochure

Your opening is where most personal statements die. If you start with, “My interest in [specialty] began when…,” you are already sinking.

Instead, start inside a moment, specific enough that it could not possibly be anyone else’s.

Weak:

“During my third-year rotations, I was exposed to many specialties, but none intrigued me as much as internal medicine.”

Stronger:

“On day three of my internal medicine rotation, I spent an hour trying to reconcile a medication list that included both metoprolol tartrate and succinate. The patient shrugged and said, ‘I just take the blue one if I feel off.’”

That second opening does three things quickly:

- Shows you in action.

- Hints at your specialty (IM) without announcing it like a billboard.

- Feels like something that actually happened, not made-up essay fodder.

Formula you can use:

Start with:

- One concrete physical detail (sound, smell, object, phrasing).

- A line of dialogue if it is short and sharp.

- A micro-decision you had to make.

Then, in the second or third sentence, briefly anchor:

- Where we are (service, year).

- Your role.

Only after 4–6 sentences, zoom out 1–2 sentences to say what this showed you about the work you like.

You can draft 2–3 possible openings and see which one feels less like marketing copy and more like you telling a colleague a story on call.

Step 6: Make Your “Why This Specialty” Actually Adult

Most “why X specialty” sections boil down to, “I like procedures and continuity of care,” which is basically the mission statement of half of medicine.

You need to answer two specific questions instead:

- What kind of problems does your brain actually enjoy solving?

- What kind of daily work do you not hate at 3 a.m.?

Concrete examples:

Internal Medicine:

- Bad: “I enjoy forming longitudinal relationships and solving complex problems.”

- Better: “I like when a patient’s problem list looks like a puzzle I need to reassemble from scratch—when half the meds are legacy prescriptions and no one has asked why they are still on all of them.”

Emergency Medicine:

- Bad: “I thrive in a fast-paced environment.”

- Better: “I like that in the ED, my job is to make three good decisions in 10 minutes with incomplete data, instead of 30 decisions in a month with perfect workups.”

Psych:

- Bad: “I enjoy listening to patients’ stories.”

- Better: “I like the quiet moment after a patient finishes a long, disorganized explanation of why they came to clinic, when I am trying to decide what not to say next.”

Do not parrot the specialty clichés. Describe the actual work and your reaction to it.

Step 7: Translate Your Experiences Into Resident-Relevant Skills

Program directors are not trying to decide if you are a good person. They are trying to decide if you are:

- Safe.

- Not a nightmare to work with.

- Capable of growth.

- Actually interested in their type of work.

So everything you include needs to point at resident-relevant skills. Not abstract virtues.

Here is how to reframe:

Instead of:

- “Through research, I learned perseverance.” Use:

- “Running a prospective chart review taught me to be methodical about data—double-checking dates, clarifying definitions, and admitting when inclusion criteria were too vague. That same habit now slows me down just enough when I write discharge summaries.”

Instead of:

- “Volunteering improved my empathy.” Use:

- “Calling patients to explain prep instructions forced me to stop relying on stock phrases and start asking, ‘Can you tell me how you will do this step?’ to catch misunderstandings before they showed up as no-shows.”

You are always connecting: Experience → Specific behavior → Resident role

This is what most applicants skip. They name-drop experiences assuming PDs will do the interpretation work. Do not make them.

Step 8: Clean Up the Ending Without Sounding Like a Robot

The last paragraph should not sound like the author died and a committee took over.

Bad:

“In conclusion, I believe my clinical experiences, research background, and passion for patient care have prepared me to be an excellent resident. I am excited for the opportunity to continue my training at your program.”

This says nothing.

You want three simple moves:

One sentence looking backward

What all of this has clarified for you.Two sentences looking forward

What kind of training and growth you want.One clean closing line

Simple. Human. Not begging.

Example:

“These experiences have clarified that I want a career spent with complex, medically vulnerable patients whose problems do not fit neatly into one clinic visit. I am looking for a residency that values careful thinking on the wards, honest feedback, and opportunities to follow patients over years, not weeks. I still have a great deal to learn, but I bring curiosity, steadiness on long call days, and a willingness to do unglamorous work well. I look forward to contributing to and growing within a program that shares these priorities.”

Does it sound a bit formal? Yes. That is fine. But it does not sound like a cardboard template.

Step 9: Fix Flow, Voice, and Bloat in One Editing Pass

Now you have:

- Less fluff.

- Better stories.

- Clearer specialty reasoning.

Time to make it read like one coherent piece, not stitched fragments.

Do a “read out loud” pass

Out loud. Not in your head. That is where you catch the stiffness.

As you read, fix:

- Sentences longer than 3 lines. Break them.

- Repeated sentence openings (“I…” “I…” “I…”).

- Overused words: passion, privilege, unique, invaluable, invaluable (yes, twice), inspired, journey.

You want some variation:

- Mix a few short sentences for punch.

- Accept one or two fragments for rhythm.

- Allow one personal aside if it feels natural: “I did not say anything at the time, but I kept thinking about it on the bus home.”

Check paragraph balance

Common problem: 80% of the essay is early life + “I love X specialty,” and 20% is what you are like as a team member.

Reverse that. Programs care about who is showing up on July 1, not your childhood volunteering.

Aim for something like:

| Section Focus | Approximate Share |

|---|---|

| Anchor story + reflection | 35–40% |

| Why this specialty (real reasoning) | 20–25% |

| Evidence of how you work on a team | 25–30% |

| Brief background + closing | 10–15% |

If your childhood or college hardships are relevant, you can mention them. Just do not let them eat the statement. One short paragraph is enough in most cases.

Step 10: Sanity-Check Against Red Flags and Over-Sharing

You can be honest without making a PD nervous.

Watch out for:

Unresolved issues

If you mention burnout, mental health struggles, professionalism incidents, or major conflicts, you must show:- Clear resolution.

- Concrete changes in behavior.

- No lingering victim narrative.

Overly graphic or dramatic stories

You are not writing a novel. You do not need gore or soap-opera-level drama to be compelling. In fact, it often backfires and sounds performative.Hero fantasies

If your story makes you sound like the lone savior who saw what no one else did, check the humility. You were a student. Keep that perspective.Excessive self-criticism

One moment of growth is fine. But if half your essay is about your weaknesses, you look unstable, not self-aware.

A good rule: if you would hesitate to discuss a topic briefly, calmly, and clearly in an interview, do not make it the centerpiece of the statement.

Step 11: Get Targeted Feedback (Not a Committee Rewrite)

At this stage, most people either:

- Show it to no one, or

- Show it to everyone and get conflicting advice that ruins their voice.

Here is a better approach:

Pick 2–3 readers, max:

- One resident or fellow in your specialty.

- One faculty member or advisor who actually reads personal statements.

- Optional: one non-medical person for clarity (if your writing tends to get too jargony).

Give them specific questions:

- “What three words come to mind about me after reading this?”

- “Where does it feel generic?”

- “Where do you want more detail?”

Ignore:

- Cosmetic wording suggestions that erase your voice.

- Requests to add your entire CV back into the statement.

You want feedback on impression and clarity, not line-editing you into a different person.

Then do one more revision pass. Not five.

Step 12: Do a Final Technical Pass Before Submitting

Last, the boring but necessary cleanup.

Length:

Stay in the recommended range for ERAS (about one page, ~650–800 words is usually safe). If you are at 1,200+, you have not cut enough.Formatting:

- Single spaced.

- Clear paragraph breaks.

- No weird symbols from copy-paste.

- No headers, no footers, no personal contact info in the statement itself.

Names:

- No program names. You cannot customize per program in ERAS without risk.

- If you accidentally write “I would be honored to train at [Program],” you will forget to change it and send it to 30 other places. Do not do this.

Consistency:

- Dates, rotations, and experiences should line up with your CV.

- If you emphasize research here, make sure it is present on the application.

If you want, you can treat this like a checklist and literally tick them off.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis & Cutting | 20 |

| Story Rebuild | 40 |

| Specialty Reasoning | 20 |

| Polish & Feedback | 20 |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Identify Generic Draft |

| Step 2 | Cut Fluff and Clichés |

| Step 3 | Choose 1-2 Anchor Stories |

| Step 4 | Rewrite Opening and Specialty Rationale |

| Step 5 | Add Concrete Team-Based Evidence |

| Step 6 | Edit for Voice and Flow |

| Step 7 | Targeted Feedback |

| Step 8 | Final Technical Cleanup |

If You Are Completely Stuck

If you have cut, stared, and still feel like you are writing nonsense, use this bare-bones prompt to reset:

Write, without worrying about grammar or style, answers to these three questions in a separate document:

Describe one patient encounter or moment on rotation that you still think about.

- What do you remember visually?

- What were you afraid of at the time?

- What did you do that you are either proud of or wish you had done differently?

Describe a time in medical school when you changed how you work.

- What was wrong with how you were working before?

- What forced the change?

- What concrete new habit did you build?

Describe a clinic or service day that felt like, “Yes, I could do this for years.”

- What exactly were you doing most of the time?

- What type of patients were you seeing?

- What did you like about how the team functioned?

Then, lift the best 2–3 paragraphs from those free-writes and rebuild your statement around them. Some of your most honest writing will be in those messy answers.

The Core Fix, In Brief

Three things rescue a generic personal statement every time:

Specific stories instead of abstract claims.

Stop telling us you are empathetic, hardworking, or passionate. Show us the moment when that actually mattered.Adult reasoning about your specialty.

Replace clichés with clear descriptions of the work you like and the problems your brain wants to solve.Evidence that you will function on a team.

Use 2–3 concrete behaviors to show how you think, work, and respond to pressure—because that is what residency really cares about.

If you do those three things, your personal statement will stop sounding like everyone else’s. Not because you sprinkled in bigger adjectives, but because you finally wrote like a specific person who is ready to do real work.