Your “chaotic” medical school journey is not the problem. The problem is that you are trying to tell it in the wrong shape.

Residency personal statements fall apart for one main reason: the writer tries to list everything instead of proving one thing. That is exactly how messy trajectories end up sounding even more chaotic on paper.

You fix this by doing the opposite of what your anxious brain wants to do.

You do not need to hide the twists. You need to organize them around a single, sharp through‑line.

Let me walk you through how.

Step 1: Stop Calling It “Chaos” And Define the Actual Pattern

First, we are going to strip the drama out of “chaotic journey.”

Most “chaotic” paths fall into a few very standard buckets. I have seen these dozens of times:

- Step failures or repeats (Step 1 fail, Step 2 retake)

- Leaves of absence (mental health, family illness, pregnancy, burnout)

- Specialty changes (surgery to psych, EM to IM, etc.)

- Academic bumps (remediated course or clerkship, delayed graduation)

- Non‑linear paths (prior career, extended research, dual degrees, extra years)

- Institutional disruptions (school lost accreditation, COVID rotations destroyed)

Your first job is not to “sound impressive.” It is to name the pattern of your journey as a PD would see it.

Use this simple filter:

“If a program director glanced at my ERAS in 30 seconds, what 1–2 sentences would they say to describe my path?”

It might sound like:

- “Took 6 years to finish med school with a leave of absence for depression, then solid Step 2.”

- “Non‑traditional: former engineer, did MPH between MS2 and MS3.”

- “Struggled early (Step 1 fail, remediation), clearly improved on clinical years and Step 2.”

- “Switched from surgery to family medicine after a research year.”

Write your version. One sentence. Brutally honest.

That “PD summary” is the reality you must work with. Your personal statement’s job is not to erase it. Your job is to reframe it as intentional growth.

Step 2: Choose One Core Theme (Not Three. Not Seven.)

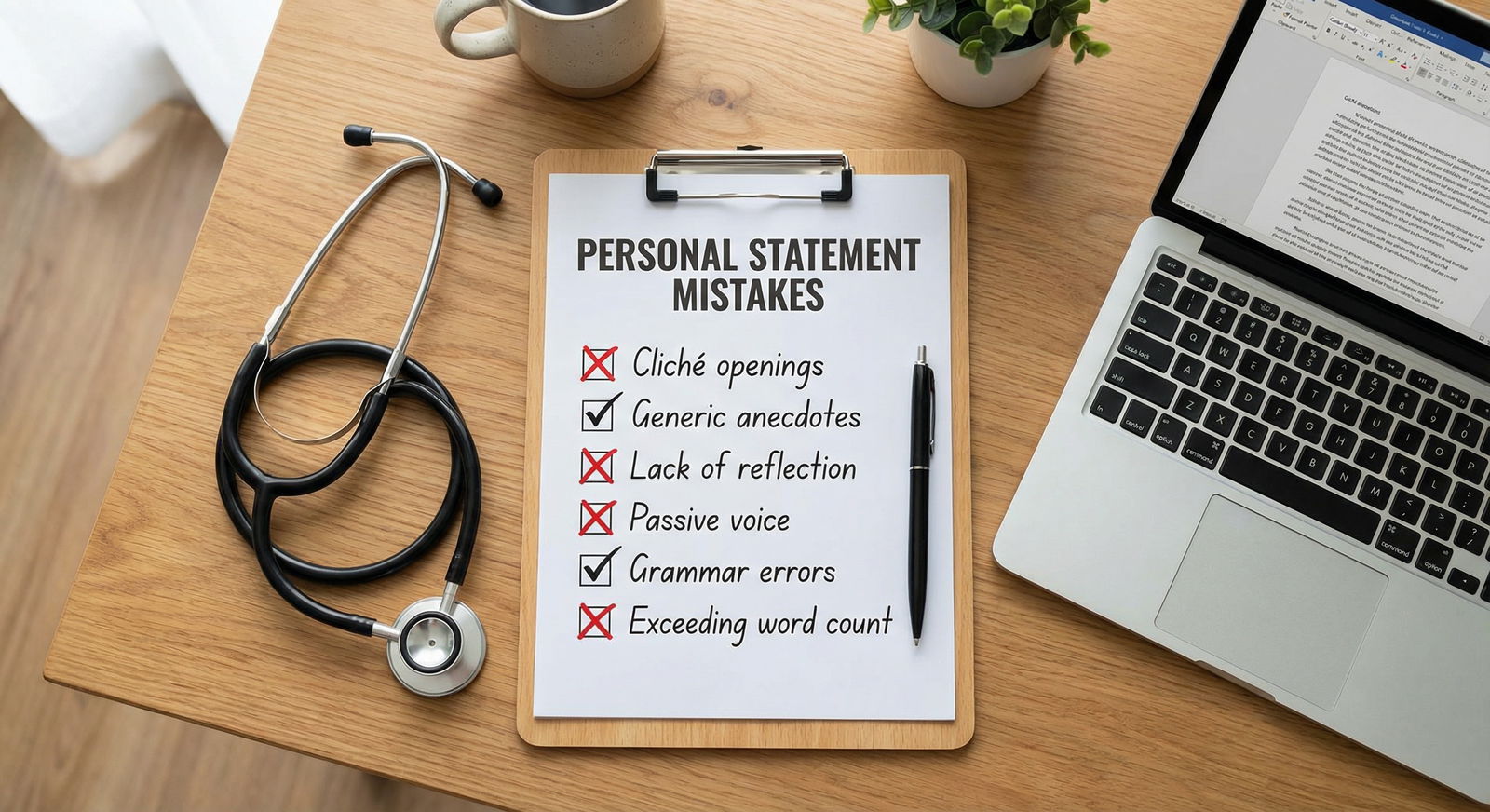

The biggest mistake I see with “messy” stories is theme sprawl.

People try to be:

- Resilient

- Compassionate

- Curious

- Leader

- Researcher

- Teacher

- Innovator

- Humanistic

…in 750 words.

You cannot do that and stay coherent.

You need one primary theme that runs the show, plus maybe one supporting thread.

Think in verbs, not adjectives. Verbs are easier to prove with concrete scenes.

Strong primary themes for non‑linear journeys:

- “I adapt under pressure and come back stronger.”

- “I deliberately redesigned my training to be better at X.”

- “I move toward depth, not prestige or convenience.”

- “I pay attention when the work is not right, and I correct course.”

- “I learn fast from failure and change my behavior.”

Weak themes:

- “I have always wanted to be a doctor.” (No one believes “always” and your ERAS says otherwise.)

- “I love science and people.” (Every applicant says this.)

- “I am passionate about internal medicine.” (Empty unless you show how.)

Pick one theme that matches your PD summary from Step 1. For example:

- PD summary: “Step 1 fail, Step 2 247, strong clinical evals.”

- Good theme: “I treat setbacks as feedback and use them to build better systems.”

- PD summary: “Took a year off for depression recovery, came back with high honors on rotations.”

- Good theme: “I learned to set boundaries and build sustainable habits, which made me a more reliable team member.”

- PD summary: “Started as surgery‑bound, switched to psych after serious family mental health event.”

- Good theme: “When reality contradicts my plans, I am willing to listen and change direction, even when it costs me.”

Write this theme as a one‑sentence thesis at the top of your planning document. The rest of your essay must obey this sentence.

Step 3: Build a Simple 3‑Act Spine for Your Story

You are not writing a diary. You are building a narrative spine: a clear before → pivot → now.

Use this 3‑act structure. It works across specialties, chaos levels, and backgrounds.

Act I – Before (Setup + early flaw)

- Where you started.

- What you thought medicine or your specialty would be.

- The blind spot, weakness, or misconception that led to later problems.

Act II – Disruption (The “chaos” + response)

- The setback, delay, failure, or change.

- How you reacted emotionally and behaviorally.

- What you actually did differently, over time.

Act III – After (Evidence you are now stable + aligned)

- What you are like to work with now.

- Concrete proof: rotations, roles, projects, patient care.

- How this trajectory prepares you to be a better resident in this specialty.

That is it. Three acts. No need for creative gymnastics.

Let me sketch a concrete example.

Scenario: Step 1 fail + LOA for mental health + strong Step 2 + honors in M3.

- Act I: You came in overconfident, relied on cramming, tied self‑worth to scores, never asked for help.

- Act II: You failed Step 1. Depression, shame, avoidance. Then—forced to confront your habits—you built new systems: scheduled study blocks, peer groups, therapy, exercise. Second attempt: pass with big jump. Returned to rotations using those same systems.

- Act III: On wards, those systems make you reliable. Notes done early, reading each night, receiving feedback without crumbling. Attendings comment on your preparation. Step 2 shows consistency. You want internal medicine because you like long arcs of care, which match how you have learned to work: long‑term, systematic, not last‑minute heroics.

Notice what is happening: the “chaos” is now Act II of a deliberate development arc, not random misfortune.

Step 4: Identify 2–3 Anchor Scenes That Prove the Theme

You do not need to describe every year of medical school. Stop trying.

You need 2–3 specific scenes that carry your theme.

Each scene should:

- Involve you making a decision or changing behavior.

- Show a tension or problem.

- End with a concrete outcome or insight.

- Connect to who you are as a future resident.

Typical anchor scene options:

- The moment you realized your old way of studying was failing you.

- A specific patient encounter that crystallized your switch in specialty.

- A conversation with a mentor that changed how you handle stress.

- A concrete example from a rotation where your “new” self showed up differently.

- A research or QI moment where you chose substance over résumé padding.

Let me make this practical.

Example: Theme – “I learn from failure and build systems.”

Possible anchor scenes:

Studying for first Step 1

- You memorized question bank explanations, skipped Anki reviews, pulled late nights.

- Snapshot: Exhausted at 2 a.m., flipping through 200 flashcards, telling yourself you will “fix it next week.”

After failing Step 1

- Sitting in a professor’s office, saying, “I do not know how to study any other way.”

- Mentor forces you to schedule blocks, track practice scores, sleep. You hate it at first.

On medicine clerkship months later

- You use the same tracking system for patient follow‑up.

- You keep a running list of “tomorrow tasks,” review cases at night, show up with plans.

- Senior resident: “You are surprisingly organized given your test history.” That line stays in your head.

Those three scenes, if written concretely, show a clear behavioral arc: chaotic → humbled → systematic → reliable.

That is your theme, proved.

Step 5: Map Your Life Events to the Theme (Not the Other Way Around)

Most people start with a list of everything they have done and then hunt for a theme to glue it together. Backwards.

Now that you have:

- PD summary (Step 1)

- One‑sentence theme (Step 2)

- 3‑Act spine (Step 3)

- 2–3 anchor scenes (Step 4)

You look at your actual events and decide which ones serve the story.

Grab a blank page. Make three columns:

- Column 1: “Events”

- Column 2: “What it shows about me”

- Column 3: “Does it serve my theme? (Y/N)”

| Event Type | What It Shows | Keep? |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 fail | Old habits, wake-up call | Yes |

| LOA for depression | Vulnerability, boundaries | Yes |

| Surgery research project | Technical skill, perseverance | Maybe |

| Volunteer free clinic | Long-term commitment | Yes |

| High Step 2 | Growth, new system works | Yes |

If something does not serve the theme, it is noise. You can cut it or give it a single supporting sentence at most.

This is where you kill the urge to jam in every line of your CV. PDs see your ERAS. The personal statement is for sense‑making, not inventory.

Step 6: Use This Simple Paragraph Blueprint

You have the structure. Now you need sentences that behave.

Here is a no‑nonsense blueprint that keeps chaos under control:

Opening paragraph (4–6 sentences)

- Drop us in a specific moment (not birth, not middle school).

- Hint at the flaw or misconception.

- Land the paragraph with your core theme.

Body paragraph 1 – The disruption (6–9 sentences)

- Describe the challenge/failure/change clearly and briefly.

- Focus on your response: what you changed, who you involved, what you learned.

- Avoid self‑pity; emphasize agency.

Body paragraph 2 – Proof of transformation (6–9 sentences)

- Show later rotations, work, or roles where your new habits/insights show up.

- Include at least one concrete patient or team interaction.

- Tie behaviors directly to residency‑relevant skills (reliability, communication, follow‑through).

Body paragraph 3 – Specialty alignment (4–7 sentences)

- Explain why this specialty makes sense given your journey and theme.

- Specific aspects: patient population, pace, type of thinking, continuity, procedures.

- Avoid generic “I love working with people / the whole patient.”

Closing paragraph (3–4 sentences)

- One sentence summarizing your arc (“I entered medicine as X and have become Y.”)

- One sentence on what you will bring as a resident (clear, not grandiose).

- Optional: brief nod to long‑term goals if they reinforce the same theme.

If you are rewriting a messy draft, use this as a checklist. Highlight in different colors:

- Theme sentences

- Disruption / failure parts

- Transformation evidence

- Specialty fit

If any section is all disruption and no transformation, fix it. If specialty fit feels generic, sharpen it.

Step 7: Address Red Flags Directly, Briefly, and With a Pivot

Your personal statement does not need to become an explanation letter, but if you have obvious red flags, you cannot pretend they do not exist.

What counts as an obvious red flag:

- Step failures

- LOA

- Extended time to graduation

- Major specialty switch late in the game

- Big GPA drop

- Conduct or professionalism issues (if on record)

How to handle them:

Name it once, clearly.

- “I failed Step 1 on my first attempt.”

- “I took a year‑long leave of absence for treatment of major depression.”

No euphemisms. Program directors see right through those.

Give minimal factual context.

1–2 sentences.- “At the time, I relied on last‑minute studying and avoided asking for help, a pattern that had worked in college but broke under the volume of medical school content.”

- “I had ignored worsening depressive symptoms until they significantly interfered with my functioning.”

Spend the bulk on your concrete response.

This is where most people fail. They stop at “I learned resilience.” Meaningless. Show it.- “With my dean and therapist, I built a daily schedule that prioritized consistent studying, sleep, and exercise, and I checked in weekly with a faculty mentor to review practice scores and adjust my plan.”

End the section with clean evidence.

- “My Step 2 score of 247 and consistent honors in clinical clerkships reflect these new habits.”

Notice what you are doing:

- Owning the problem.

- Demonstrating insight.

- Showing behavior change.

- Providing data that the change is real.

That is what reassures programs. Not perfection.

Step 8: Make Your Specialty Choice Look Like a Logical Endpoint, Not a Plot Twist

Chaotic journeys often come with last‑minute specialty changes. That scares some PDs if it looks impulsive.

You need to show that your specialty choice is the natural consequence of your path, not a random pivot.

Use this quick test:

Can I explain my specialty choice in 2–3 sentences that build directly on my theme?

Examples:

Theme: “I moved from sprinting to sustainable, long‑arc work.”

- IM: “Internal medicine fits the way I now work: slowly, systematically, over time. The chance to follow patients through complex, chronic illnesses rewards the long‑term habits I built recovering from academic setback.”

Theme: “I listen when reality contradicts my plan.”

- Psych: “During my leave of absence for depression, psychiatry shifted from an abstract subject to a concrete lifeline. Returning to rotations, I found that the conversations I valued most were the ones that made patients feel actually understood. Psychiatry is where that work is the point, not the side effect.”

Theme: “I build systems from chaos.”

- EM: “In the emergency department, chaotic situations are the rule. What I once experienced as personal chaos in my own training is now an asset. I am comfortable stepping into disorganized scenes, prioritizing actions, and creating a framework for the team.”

If you cannot do this test in 2–3 sentences, your specialty paragraph is going to read generic. Fix it before you write.

Step 9: Cut the Filler That Makes Chaotic Journeys Sound Worse

Certain habits make non‑linear paths look even less focused than they actually are.

Here is what to delete without mercy:

Origin myths

- “I have wanted to be a doctor since I was five.”

No one on a non‑linear path believes this, and even if it is true, it is not helping you.

- “I have wanted to be a doctor since I was five.”

Random childhood anecdotes

- Third grade science fair. Grandmother’s illness. These almost never connect tightly enough to your theme.

Vague virtue claims

- “These experiences taught me resilience, empathy, and dedication.”

If the word could go on a motivational poster, cut it or replace it with a specific behavior.

- “These experiences taught me resilience, empathy, and dedication.”

CV rehash

- Listing every research project, leadership role, or volunteer gig.

PDs can already see it. Only mention items that advance your theme.

- Listing every research project, leadership role, or volunteer gig.

Excessive apology

- “I am deeply sorry for my failure and I know I let people down…”

One sentence acknowledging regret is enough. After that, focus on what you changed.

- “I am deeply sorry for my failure and I know I let people down…”

Fewer, sharper details make you look more in control of your story. And control is what PDs want in a resident.

Step 10: Run the “Program Director Read” Test

When you have a solid draft, imagine a tired PD at 11:30 p.m. on their laptop skimming your file.

They give your statement 60–90 seconds, max.

You want them to walk away with:

- A clear, one‑sentence idea of who you are now.

- A sense that your challenges are understood and resolved, not festering.

- A reason your path fits their specialty and training environment.

Do this concretely:

- Print the statement or open it on screen.

- Set a 90‑second timer.

- Read at a normal skim speed.

- Then answer, in writing:

- “What is this applicant’s main theme?”

- “What is their biggest past issue?”

- “Why did they pick this specialty?”

- “What evidence do I have that they will be stable and useful on day 1?”

If you cannot answer those in one sentence each, the statement is still muddled. Go back and tighten.

If the “biggest past issue” does not show up at all, that is also a problem when your ERAS screams it. Add a clean, brief acknowledgment.

Visualizing the Process So You Do Not Get Lost

Here is the actual flow I push people through when we fix their “messy story” drafts:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start: Chaotic Journey |

| Step 2 | Write PD Summary |

| Step 3 | Choose One Core Theme |

| Step 4 | Build 3-Act Spine |

| Step 5 | Select 2-3 Anchor Scenes |

| Step 6 | Map Events to Theme |

| Step 7 | Draft with Paragraph Blueprint |

| Step 8 | Address Red Flags Briefly |

| Step 9 | Align Specialty with Theme |

| Step 10 | Run PD Read Test |

| Step 11 | Revise for Clarity and Focus |

And to keep yourself honest about where your words are going:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Transformation & Evidence | 350 |

| Specialty Fit | 200 |

| Disruption/Setbacks | 150 |

| Opening/Closing | 150 |

Target total: roughly 750–850 words.

Notice the distribution:

- Most words → transformation and concrete evidence.

- Medium chunk → why your specialty fits your new self.

- Smaller chunk → describing setbacks.

- Smallest → polished opening/closing.

Most applicants invert this. They overspend on drama and underspend on proof. Do not.

Final Check: What “Cohesive” Actually Looks Like

You will know you have a cohesive theme, even with a chaotic path, when:

The same idea keeps showing up in different ways.

(Example: “I build systems from chaos” appears in studying, rotations, QI, and specialty choice.)Your “failures” feel like necessary steps in your development, not random disasters.

A stranger could read your statement and say,

“Ah, this person used to [X], then [disruption], now they are [Y], which fits [specialty] because [Z].”

If you are not there yet, you are not broken. You are just early in the drafting process.

Strip it back to:

- One sentence PD summary.

- One sentence theme.

- Three‑act structure (before / disruption / after).

- Two to three anchor scenes.

Build from there. Brick by brick.

The Short Version: What You Must Remember

Your chaos is not the issue. The lack of a single, disciplined theme is.

Decide what your story is about in one sentence, then make every paragraph serve that sentence.Red flags do not disqualify you, but vague reflection does.

Name the problem clearly, spend more time on your behavioral response than on the event, and back it up with clean evidence of improvement.Your specialty choice must look inevitable, not impulsive.

Tie your path and your theme directly into why you fit this field’s mindset and work, using specific, grounded reasons, not clichés.

Do this, and your “chaotic” medical school journey stops looking like a liability. It starts looking like what it really is: proof that you can take a hit, learn fast, and show up stronger. Which is exactly what people want in a resident.