Weak personal statements do not get “tweaked.” They get rebuilt. From the studs.

If your current residency personal statement feels generic, unfocused, or just painfully boring, you do not need another list of vague tips. You need a structured rewrite plan that forces you to make hard choices about what matters and what does not.

Here is that plan. Five steps. In order. You do not skip ahead. You do not “kind of” do them. You run the protocol and you end up with a statement that is sharper, more memorable, and actually helps you match.

Step 1: Diagnose Why Your Personal Statement Is Weak

You cannot fix what you have not correctly named.

Most weak residency personal statements fall into the same predictable failure buckets. I have seen hundreds. The patterns repeat.

Here are the main problems, and you need to identify exactly which ones you have:

The “CV in paragraph form” problem

- You are rehashing:

- Clerkships

- Research projects

- Leadership roles

- All facts that are already in ERAS.

- No real insight. No narrative. No personality. Just a prose version of your application.

- You are rehashing:

The “trauma dump” or “sob story” problem

- Overly detailed personal hardship (illness, family tragedy, immigration story, etc.)

- Very little about:

- Who you are as a resident

- How you function on a team

- How you think clinically

- Programs are not therapy clinics. They want resilience and growth, not raw suffering with no clear arc.

The “I love helping people” cliché problem

- Phrases that make Program Directors’ eyes glaze over:

- “I have always wanted to help people…”

- “Medicine allows me to combine my love of science and service…”

- “Ever since I was a child…”

- You could paste these lines into thousands of other applicants’ statements and nothing would change.

- Phrases that make Program Directors’ eyes glaze over:

The “wandering narrative” problem

- No clear spine to the essay.

- Paragraphs feel like random scenes:

- shadowing in high school

- college research

- a global health trip

- a touching patient moment

- No focused answer to: Why should we train you in this specialty?

The “specialty not actually clear” problem

- You think you are writing for Internal Medicine, but the statement:

- Could also apply to Family Med

- Could also apply to Pediatrics

- Could honestly apply to anything

- You mention the specialty name twice and think that is enough. It is not.

- You think you are writing for Internal Medicine, but the statement:

The “try-hard writing” problem

- Overly flowery language:

- “As the sun set over the parking lot of County General, I realized…”

- Forced metaphors:

- “Medicine is like a symphony…”

- Program Directors are skimming hundreds of these. If yours reads like you are auditioning for a creative writing MFA, they stop trusting your judgment.

- Overly flowery language:

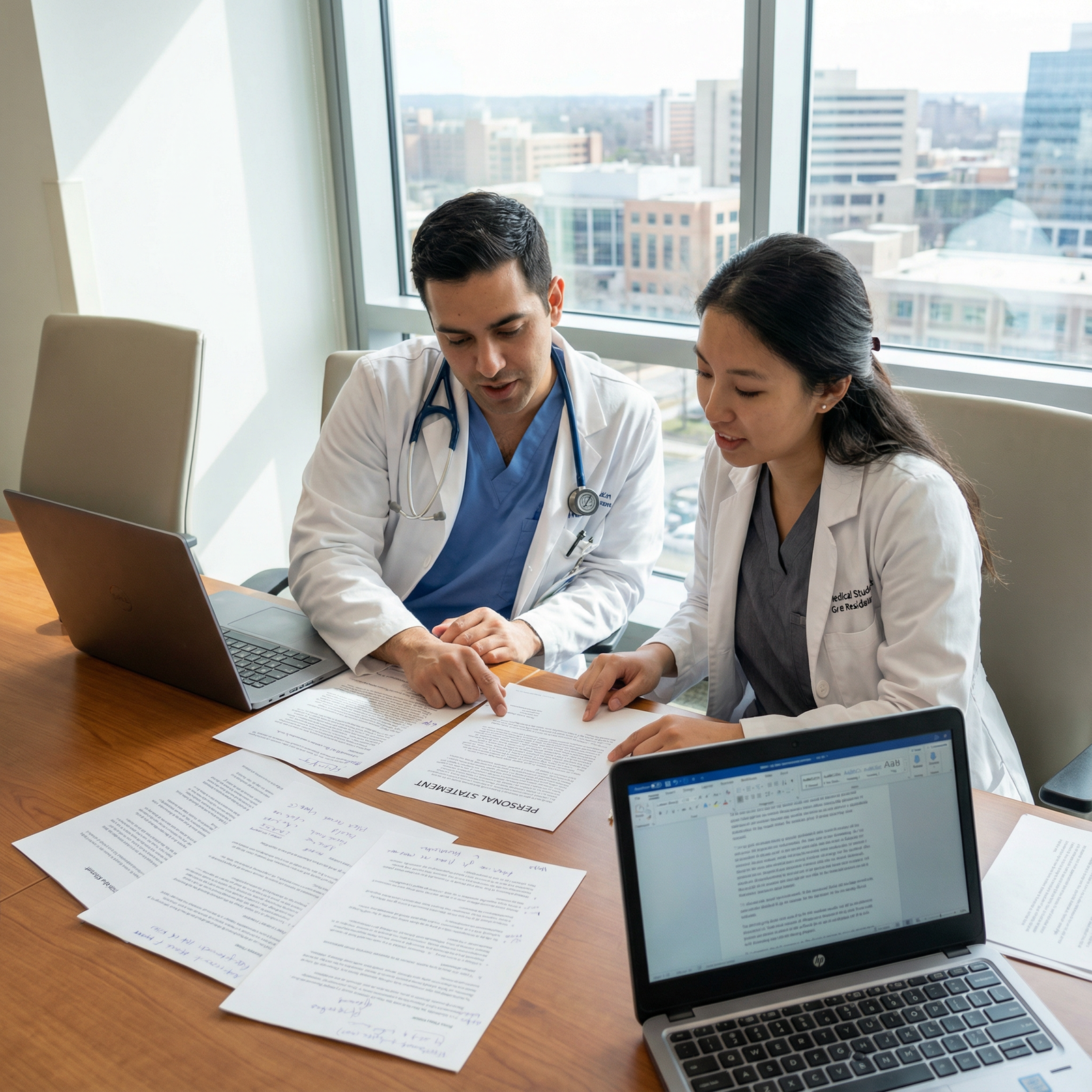

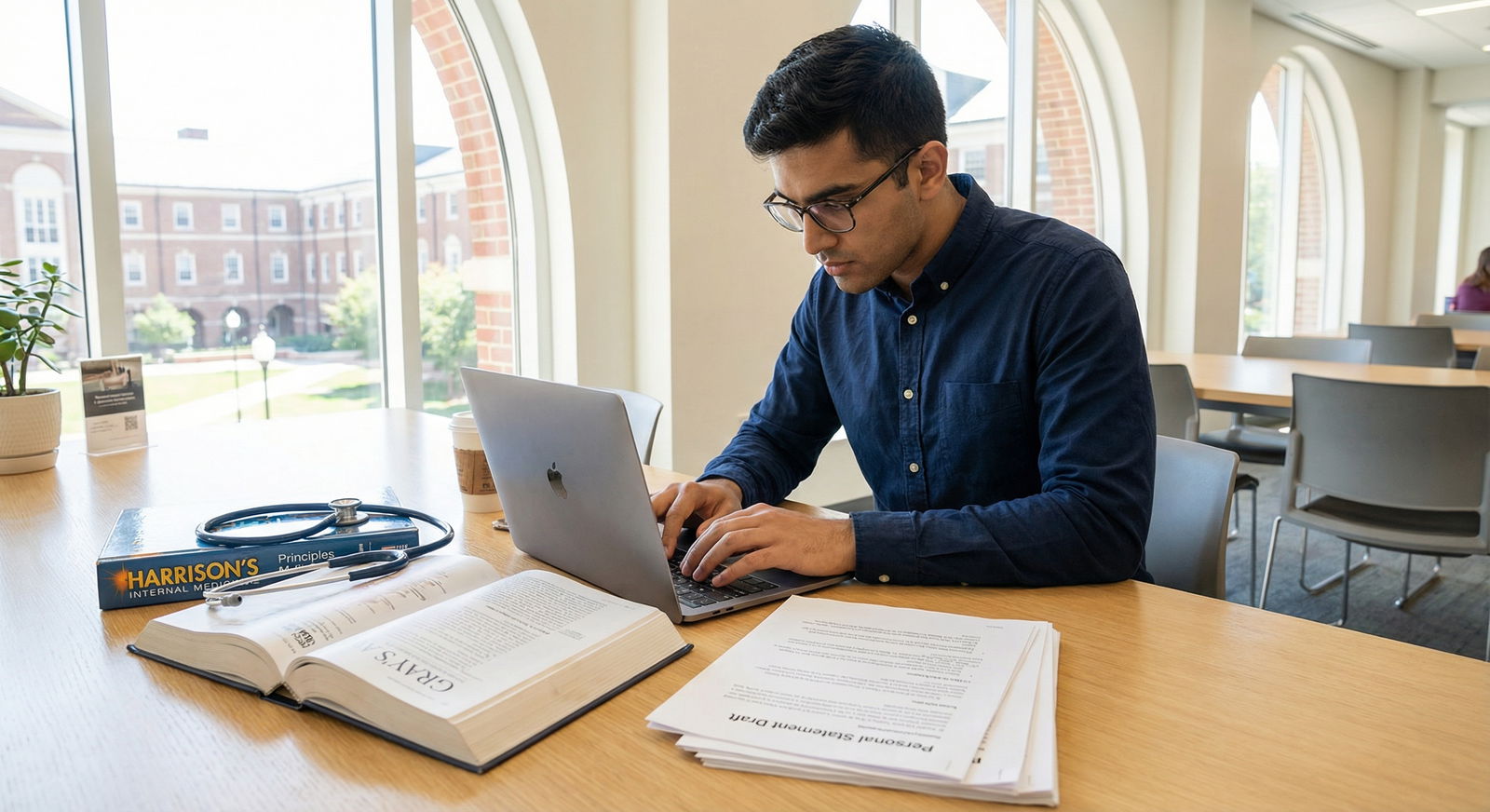

Do a Brutal 10-Minute Self-Audit

Print your current statement. Pen in hand, run this checklist:

- Circle any cliché phrases (“always wanted,” “help people,” “passion for medicine,” “ever since”).

- Put a box around any sentence that could appear in at least 1,000 other applicants’ statements.

- Underline any specific, concrete detail that only you could write (exact patient scenario, a quote you actually heard on rounds, a moment that is particular to your training).

- On the side of each paragraph, write its function in 2–3 words:

- “Why this specialty”

- “Who I am on a team”

- “Clinical growth”

- “Random story?”

- “CV dump”

- “Fluff”

If you cannot label clear functions, or you have more fluff/CV dump than “Why this specialty / Who I am as a resident,” your statement needs a full rebuild. Not a polish.

Step 2: Strip It Down To a Clear Core Message

A strong personal statement can be summarized in one sharp sentence:

“I am a [type of person / learner] who thrives in [type of environment], and I am specifically a good fit for [specialty] because [2–3 specific reasons].”

That is your core message. Everything else should serve it.

Do This Exercise (No More Than 20 Minutes)

Answer these questions in bullet form, not prose:

- Why this specialty and not others?

- What kind of resident do you actually want to be?

- What do attendings consistently praise you for?

- What do you struggle with (and how are you addressing it)?

- What kinds of patient encounters stay with you days later?

- What parts of the work put you in “flow” where you lose track of time?

Force yourself to pick 2–3 core themes. Examples:

- Calm in acute situations; loves diagnostic complexity; values longitudinal relationships.

- Systems thinker; obsessed with workflow efficiency; enjoys teaching juniors.

- Deeply curious about pathophysiology; strong follow-through; thrives on multidisciplinary teams.

Write your one-sentence backbone. For example:

- “I am a calm, detail-focused clinician who thrives in high-acuity, team-based environments, and I am drawn to Emergency Medicine because I enjoy rapid clinical decision-making, procedural work, and caring for underserved patients at critical moments.”

- “I am a reflective, systems-minded internist-in-training who loves untangling complex diagnostic problems, coordinating care across disciplines, and building long-term relationships with medically complicated patients.”

That backbone is not your opening line. It is your internal north star. If a paragraph does not clearly support that message, it gets cut. No debate.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Why this specialty | 35 |

| Who you are as a resident | 30 |

| Key experiences & stories | 25 |

| Personal background context | 10 |

Step 3: Rebuild the Structure (Before You Touch Sentences)

Most weak statements are structurally broken. You cannot “edit” your way out of that.

Build a clear 4-part skeleton first. Think architecture, not wallpaper.

A Simple, High-Yield Structure

You can adapt this, but do not get fancy until you have something this clean working.

Opening: One focused clinical moment (1 short paragraph)

- Not your childhood.

- Not “ever since I watched ER…”

- A real moment from medical school or early residency where:

- Your current self is present.

- We see you think, act, and reflect as a near-physician.

Middle 1: Why this specialty (1–2 paragraphs)

- Anchor in specific elements of the work:

- Types of patients

- Typical problems

- Team structure

- Clinic vs inpatient vs OR

- Show how your traits and experiences line up with that reality.

- Anchor in specific elements of the work:

Middle 2: Who you are as a resident (2–3 paragraphs)

- Go through 2–3 stories or patterns that reveal:

- How you handle responsibility

- How you respond to feedback

- How you function on a team

- How you think clinically and ethically

- Less “what you did,” more “how you operate.”

- Go through 2–3 stories or patterns that reveal:

Closing: Future direction + program fit (1 paragraph)

- Brief, forward-looking:

- Type of resident you aim to be

- Skills you want to strengthen

- How you see your career evolving (general direction, not locked-in fellowship fantasy)

- Brief, forward-looking:

Example Skeleton (With Functions, Not Full Sentences)

Paragraph 1:

- Function: Clinical vignette showing you in action.

- Content: A specific patient on [relevant rotation] where you:

- Faced uncertainty

- Had to communicate with team / family

- Learned something that reshaped how you see the specialty

Paragraph 2–3:

- Function: Connect that moment to why you chose the specialty.

- Content:

- 2–3 concrete aspects you like:

- EM: undifferentiated patients, rapid triage, shift work, broad scope

- IM: diagnostic puzzles, chronic disease management, complex comorbidities

- Surgery: immediate impact, technical challenge, team-based OR culture

- How past experiences confirmed this fit (specific rotations, mentors, habits)

- 2–3 concrete aspects you like:

Paragraph 4–6:

- Function: Who you are as a resident.

- Content:

- A story where you took ownership over a patient or task

- A time you received hard feedback and changed your approach

- A situation that reveals your reliability, resilience, or curiosity

Paragraph 7:

- Function: Future direction and tone.

- Content:

- What you want from training

- What you bring to a program

- A grounded, humble but confident closing sentence

You should be able to point to each paragraph and say, “This exists because it shows [specific trait] or explains [specific reason I fit this specialty].”

If any paragraph’s function is “nice story I like,” delete it. You are not writing a memoir.

Step 4: Replace Generic Content with Specific, Verifiable Detail

The difference between a weak and strong personal statement is almost always specificity. Vague statements are forgettable. Specific ones are memorable and credible.

Look at these pairs:

Weak: “I am passionate about caring for underserved populations.”

Strong: “On my IM sub-I at County Hospital, where most of our patients were uninsured or underinsured, I learned how to adjust complex medication regimens around cost and access rather than theoretical ‘ideal’ treatments.”

Weak: “I work well in teams.”

Strong: “During my MICU month, I made it a habit to arrive 20 minutes early, pre-brief the night intern about any pending studies, and then huddle with my co-student so we could divide tasks before rounds. It reduced dropped orders and made our attending far less irritated by 4 p.m.”

Weak: “I am a hard worker.”

Strong: “On my surgery clerkship, I scheduled my own Saturday morning suture practice sessions in the empty sim lab for six consecutive weeks, using leftover pig’s feet and the same knot-tying drills the residents used for their skills exam.”

Rewrite Protocol: Line-by-Line Pass

Print your new structured draft (even if it is rough). Then, for each sentence, ask:

Could another applicant truthfully say this exact sentence?

- If yes, change it or cut it.

- Add:

- Where you were

- What service you were on

- What you actually did or said

Is this claim supported by a concrete example elsewhere?

- If you say “I seek out feedback,” there must be a moment where you voluntarily asked for it and acted on it.

- If you say “I am calm under pressure,” show a scenario where that mattered.

Does this sentence push the story forward?

- Or is it restating what you already said with different words?

- One clean, strong example beats three watered-down ones.

Common Generic Lines and Their Fixes

“Medicine allows me to combine my love of science and helping others.”

- Replace with: “What keeps me in medicine is the daily challenge of applying pathophysiology to messy, real patients—the type who fall outside textbook algorithms—and then explaining our plan in language their family actually understands.”

“My experiences have shaped me into the person I am today.”

- Replace with something that actually shows the shaping:

“Early in third year, I would silently rewrite residents’ plans in my head. After being wrong—publicly—about a ‘simple’ pneumonia patient who ended up in the ICU, I became far more deliberate about asking, ‘What am I missing?’ and checking my assumptions against the team’s.”

- Replace with something that actually shows the shaping:

You get the idea. Kill the empty calories.

Step 5: Run the “Program Director Read” and Final Polish

Now you have a structurally sound, specific draft. Time to pressure-test it the way real programs do.

Most Program Directors and faculty read your statement under three conditions:

- They are tired.

- They are skimming.

- They have 30+ more to get through.

Your document must survive that environment.

The 90-Second Skim Test

Read your statement yourself in 90 seconds. Literally time it.

Then answer, without peeking:

- Why this specialty?

- What 2–3 traits define you as a resident?

- What is 1 specific story that stuck?

If you cannot answer those clearly, the statement fails. Fix:

- Your opening (not memorable enough)

- Your transitions (“why this specialty” not explicit)

- Your repetition (buried main points)

Get Targeted Feedback (Not a Committee Edit)

You do not need ten people to rewrite your voice. You need 1–3 people for focused questions:

- One attending or senior resident in your chosen specialty

- One peer who writes decently

- Optional: mentor/advisor who knows your trajectory

Ask them specific questions only:

- “After one read, how would you describe the kind of resident I am?”

- “Does this clearly explain why I fit [specialty] instead of something else?”

- “Where did you get bored or confused?”

- “Is there anything that feels like I am trying too hard or overselling?”

Do not ask, “What do you think?” That is how you invite unhelpful broad rewrites.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Diagnose weaknesses |

| Step 2 | Define core message |

| Step 3 | Rebuild structure |

| Step 4 | Make content specific |

| Step 5 | PD-style skim test & polish |

| Step 6 | Final statement ready |

Final Line-Level Polish (But Do Not Obsess)

At this stage, you clean, you do not re-architect.

Run one more pass for:

Bloat and redundancy

- Cut any sentence that:

- Repeats an idea already well established

- Exists purely because you like how it sounds

- Aim for ~650–800 words. Enough substance, not a novella.

- Cut any sentence that:

Tone

- Confident but not arrogant:

- Good: “I aim to be the resident who…”

- Bad: “I know I will be an outstanding resident who will excel in every task.”

- Avoid self-deprecation for humor. This is not the time.

- Confident but not arrogant:

Jargon and buzzwords

- You are not writing an NIH grant.

- Keep technical talk only where it matters: a key case or specific interest.

- Delete overused buzzwords unless you immediately ground them in specifics:

- “Leadership,” “empathy,” “resilience,” “burnout,” “advocacy”

Mechanical errors

- Grammar and spelling mistakes are not “human.” They are sloppy.

- Use spellcheck, then read aloud.

- Pay attention to:

- Subject–verb agreement

- Tense consistency (past vs present)

- Name and capitalization consistency (ICU vs I.C.U., ED vs ER, etc.)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | 10 |

| Core message | 15 |

| Structure rebuild | 30 |

| Specific detail rewrite | 30 |

| Polish & feedback | 15 |

A Concrete 3-Day Rewrite Plan

If you are close to deadlines, here is how to run this 5-step system fast without making garbage.

Day 1 (2–3 hours total)

- 30 min: Step 1 – Brutal audit of your current statement.

- 45 min: Step 2 – Core message + backbone sentence.

- 45–60 min: Step 3 – Build new outline, write rough opening + section headers.

- Stop. Do not polish. Let it sit overnight.

Day 2 (2–3 hours total)

- 90–120 min: Step 4 – Fill in the body paragraphs with specific detail.

- Aim to draft 2–3 strong stories.

- Resist editing while writing.

- 30 min: Quick pass to trim obvious fluff and make sure each paragraph has a clear purpose.

Day 3 (2–3 hours total)

- 20 min: 90-second skim test + notes.

- 40 min: Reorder, strengthen transitions, sharpen opening and closing.

- 30–40 min: Send to 1–2 reviewers with specific questions.

- 40–60 min: Apply only the feedback that:

- Clarifies your message

- Protects your credibility

- Tightens the prose

Then stop. There is a point where more editing just drains authenticity.

What A “Fixed” Statement Actually Feels Like

When you are done, your personal statement should:

- Read like one integrated story, not a scrapbook.

- Make it painfully obvious why you chose your specialty.

- Show, in concrete scenes, how you function as a budding resident.

- Contain at least one moment a reader could retell to a colleague:

“This is the student who [specific thing].”

And bluntly: it should sound like you. Not like ChatGPT. Not like a committee. Not like every other “I am passionate about…” essay in the stack.

If you follow this 5-step plan exactly—diagnose, define your core, rebuild structure, replace generic with specific, then pressure-test and polish—you will not have a perfect literary masterpiece.

You will have something better: a clear, credible, specialty-specific statement that actually helps you match.

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. How long should my residency personal statement be after this rewrite?

Aim for roughly 650–800 words. Under 600 and you usually have not shown enough about who you are as a resident. Over 850 and you are likely repeating yourself or wandering. Program Directors are busy; concise and dense beats long and padded.

2. Can I reuse my medical school personal statement and just “update” it?

No. The purpose is different. Medical school statements justify why you want to become a physician. Residency statements must answer why you fit a specific specialty and what kind of resident you will be. You can salvage a core story or two, but you must rebuild the framing, focus, and reflection around residency-level responsibilities.

3. Is it a problem if I do not have a dramatic “origin story” for my specialty choice?

Not at all. The “one magical patient who changed everything” trope is overused and often unbelievable. A steady pattern of experiences that moved you toward a specialty—combined with clear, thoughtful reflection on why the work suits you—is more convincing than a single dramatic epiphany. Programs care how you will perform over four years, not how cinematic your backstory is.