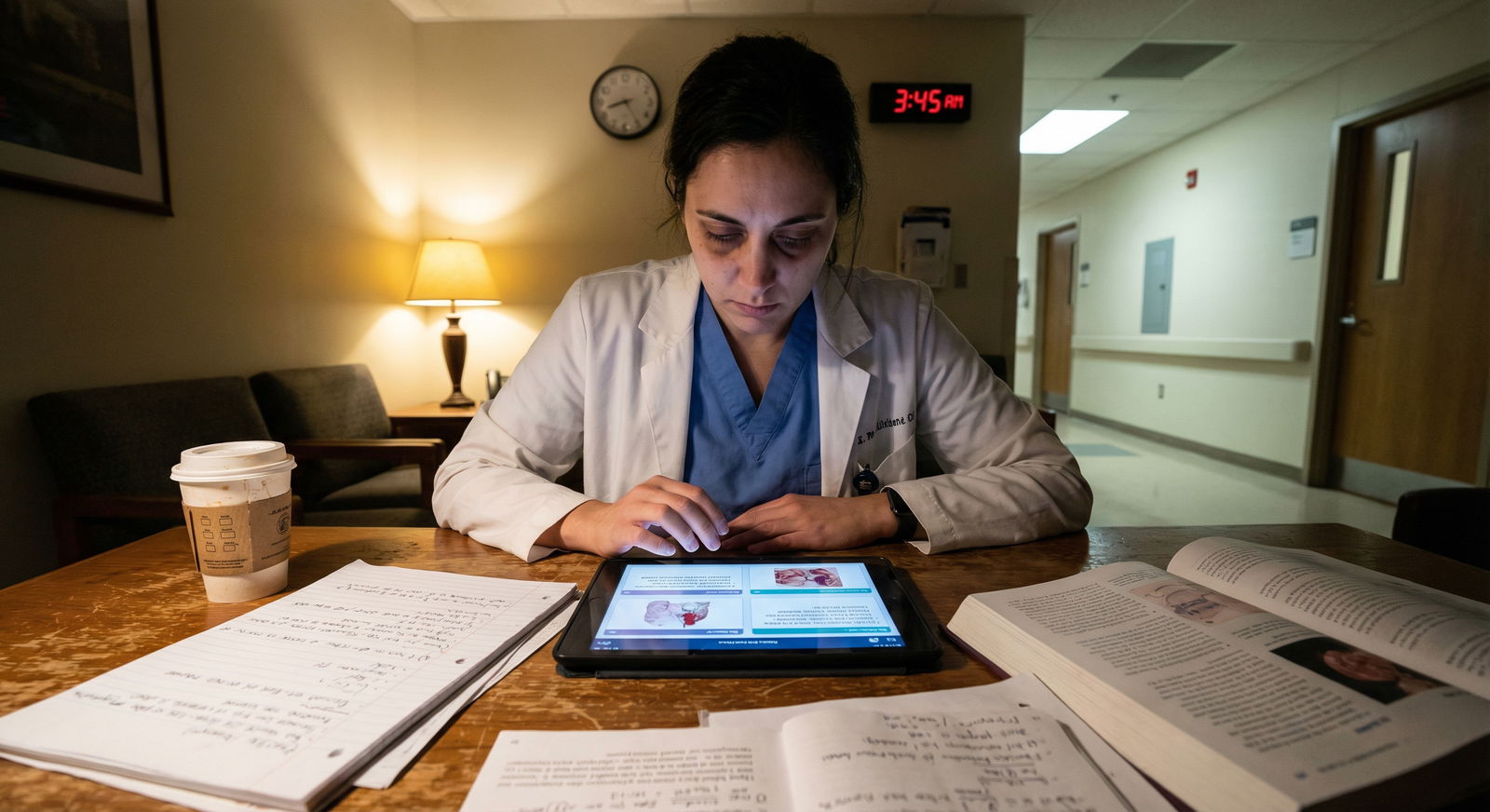

You are on night float. It is 2:17 a.m. The nurse calls: “Doc, the daughter is here, she says her mom would never want all this, and she is demanding we stop ‘everything.’ Also, this patient pulled out his NG again and is refusing labs. Do they have capacity? Can we honor this?”

You open the chart. DNR signed. No POLST. One note about “full treatment within DNR status.” You have 30 seconds to decide what to do—and in a board exam world, you have 60 seconds to pick one answer.

End-of-life and capacity questions on board exams love this chaos. But under the chaos, there are patterns. Rigid ones. If you know the patterns, you stop guessing and start scoring points.

Let me break this down.

The Four Big Frames Boards Use

First, you need the scaffolding. Most end-of-life / ethics questions are really about one of these:

- Who decides?

- What counts as a valid decision?

- What is the default when nothing is clear?

- What is the physician allowed or required to do?

Everything else is window dressing—family drama, time of day, emotional quotes. Ignore the noise. Find which frame you’re in.

Capacity vs Competence: The Most Tested Distinction

Boards will hit you over and over on this. If you mix them up, you will miss easy points.

Capacity

Clinical. Task-specific. Fluid.

A patient has capacity if they can:

- Understand the information.

- Appreciate how it applies to their own situation.

- Reason about options and consequences.

- Communicate a choice consistently.

That is the 4-part script boards are silently grading you on.

Red flags they give you to test capacity:

- Delirium, psychosis, severe depression, intoxication

- Acute hypoxia, sepsis, fluctuating sensorium

- Expressing a choice that seems “irrational” but is values-consistent

Crucial: Patients are allowed to make bad decisions. “He refuses dialysis even though he will die” is not lack of capacity by itself. The question is: does he understand and reason, not whether you agree.

Patterns:

- If the vignette describes a patient who can clearly repeat back the risks and benefits and their reasons, you must treat them as having capacity, unless the question explicitly undermines that.

- Capacity is decision-specific. A patient may have capacity to refuse a blood draw but not to sign off on a complex surgery. Boards like this nuance.

Competence

Legal. Global. Persistent until reversed.

Key pattern:

- Only a court can declare someone incompetent.

- You, as the physician, determine capacity, not competence.

So if the stem says: “The patient was previously declared incompetent by a court” → you cannot take their consent as valid. You go to the surrogate hierarchy.

If the stem says: “The patient has schizophrenia, is on meds, is calm, and can explain their choice” → they absolutely can have capacity. Mental illness ≠ automatic incapacity.

The Capacity Checklist: How Boards Want You to Think

On the exam, they frequently ask “What is the next best step?” after a patient refuses or demands something.

If capacity is questionable, the best next step is almost never “Get a psychiatrist immediately” or “Get a court order” as the first move. The correct step is usually:

- Assess decision-making capacity in a focused conversation.

This means:

- Ask the patient to repeat back their understanding of diagnosis, treatment options, and consequences.

- Ask why they prefer one option.

- Check consistency with long-standing values (if described).

- Consider reversible causes: hypoxia, meds, infection, delirium.

If that assessment is missing from the vignette and they’re pushing you, the right answer is usually some flavor of “Clarify and assess capacity before acting.” Boards love “clarify.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Patient refuses or requests treatment |

| Step 2 | Assess understanding |

| Step 3 | Assess appreciation |

| Step 4 | Assess reasoning |

| Step 5 | Assess ability to communicate choice |

| Step 6 | Respect decision |

| Step 7 | Treat reversible causes and reassess |

| Step 8 | If still impaired - use surrogate |

Surrogates and Hierarchies: Who Actually Decides?

Now the classic pattern: patient lacks capacity and no advance directive clearly answers the current situation. What next?

Exams assume a surrogate hierarchy somewhat like this (exact wording varies but order is stable):

| Rank | Surrogate Type |

|---|---|

| 1 | Court-appointed guardian |

| 2 | Durable power of attorney for healthcare (healthcare proxy) |

| 3 | Spouse or domestic partner |

| 4 | Adult children |

| 5 | Parents |

| 6 | Adult siblings |

If there is a valid, named healthcare proxy / durable power of attorney → that person wins. Even if the rest of the family disagrees. Boards will absolutely test this.

Patterns in stems:

“The patient previously filled out paperwork naming his neighbor as his healthcare proxy.”

Even if the neighbor is “only a neighbor” and the spouse disagrees, you follow the proxy.“There is no designated proxy; his estranged son has shown up and demands aggressive care; his live-in girlfriend says he never wanted that.”

Legally, the adult child usually outranks the partner if not legally married. On the exam, go with the formal legal relationship unless they explicitly tell you the law in that jurisdiction is different.

When surrogates disagree at the same level (e.g., three adult children with different opinions), your move is:

- Try to reach consensus through discussion, ethics consultation if offered in answer choices.

- Default to the option most consistent with patient’s known values and best interest, not the loudest relative.

Boards like “Ethics committee consultation” as a next step when there is conflict and time allows. They do not want you grabbing a judge as first reflex unless:

- There is severe, unresolvable surrogate conflict

- Or evidence of clear abuse / exploitation

Substituted Judgment vs Best Interest

This is another pattern they hammer.

If the patient’s prior wishes are known (verbal or written):

- Use substituted judgment.

“What would the patient choose for themselves, based on their previous statements, lifestyle, and values?”

If prior wishes are unknown:

- Use best interest.

Standard medical/ethical reasoning about what promotes well-being, function, relief of suffering.

Key exam angle:

- A surrogate’s job is not to choose what they want. It is to channel what the patient would have wanted.

So an answer that says “Ask the daughter what she wants for her mother” is worse than “Ask the daughter what the mother previously said about life support and severe disability.”

DNR, DNI, and Treatment Limitations: What They Do and Do Not Mean

Boards love to trap you on DNR/DNI scope.

DNR = Do Not Perform CPR (no chest compressions, no defibrillation, no intubation for the purpose of resuscitation after arrest).

It does not mean:

- No antibiotics

- No ICU

- No dialysis

- No pressors

- No intubation for non-arrest reasons (e.g., elective intubation before surgery or to treat reversible respiratory failure), unless specified otherwise.

So that stem where:

“A 78-year-old with DNR status develops septic shock. The nurse asks if you want to call a rapid response or just keep her comfortable since she is DNR.”

The correct answer: “Activate rapid response and treat aggressively; DNR only limits CPR after arrest.”

DNI = Do Not Intubate (no endotracheal intubation, sometimes extended to noninvasive ventilation depending on order set). Does not automatically mean “no CPR,” unless specified “Do Not Resuscitate / Do Not Intubate.”

Pattern on exams:

- Respect code status as written. If codes are ambiguous (e.g., old note vs new conversation), clarify with patient if they have capacity or with surrogate if not.

Advance Directives vs POLST/MOLST vs Verbal Wishes

You will see variations of this structure. Learn the hierarchy.

- Current, competent patient’s explicit wishes

- Valid POLST/MOLST (Physician/Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment)

- Formal written advance directive / living will

- Verbal prior statements

- Surrogate decision-making

- Physician best-interest judgment (when absolutely nothing else exists)

The exam pattern:

- If a capacitated patient now says something that contradicts an old advance directive, the current statement wins. Period. You follow the present, competent choice.

- If the patient lacks capacity, and there is a POLST filled out and signed, that is a medical order. That has more operational weight than vague family recollections.

POLST is usually for currently seriously ill or frail patients. It covers specific interventions: CPR, intubation, feeding tubes, ICU care, etc. Boards like to show you:

- A nursing home transfer with a POLST that says “DNR, Comfort-focused treatment only.”

Then the son demands full code and ICU.

Correct move: Follow the POLST. Politely explain the son does not have the authority to override a valid order clearly reflecting known wishes.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Current Patient Wishes | 100 |

| POLST/MOLST | 90 |

| Advance Directive | 80 |

| Verbal Statements | 60 |

| Surrogate Preference | 50 |

Refusing Life-Sustaining Treatment: You Must Tolerate Discomfort

Boards are blunt about this: a capacitated adult can refuse any treatment, including life-sustaining interventions. Dialysis, ventilation, chemo, antibiotics. Even nutrition and hydration. Even if it leads to death.

They will tempt you with paternalism:

- “He is depressed and hopeless; his refusal is a sign of treatable depression.”

- “His family is distraught and begs you to continue treatment.”

The correct pattern:

- Assess for depression and decision-making capacity.

- If he understands, appreciates, reasons, and communicates → respect refusal.

- Offer palliative care and symptom management.

You do not:

- Go to court to force treatment in a competent adult who refuses.

- Collude with the family to ignore the patient’s clear refusal.

Exception patterns they like:

- Suicidal intent is not the same as refusal of burdensome medical therapy in a chronic illness. Don’t confuse those. A patient refusing an insulin injection right after a suicide attempt is not capacity. A patient with metastatic cancer refusing another ICU stay might be fully rational.

Euthanasia, Physician-Assisted Suicide, and Palliative Sedation

Ethics questions here are always about what is allowed vs not, regardless of state laws.

Clear line:

- Actively administering a lethal dose of medication to cause death (active euthanasia) = not permitted in U.S. medical ethics by exam standards.

- Prescribing medications that a patient can use to end their life (physician-assisted suicide) = ethically controversial and only legal in some jurisdictions. On most board exams, the “correct” answer is: decline to participate, continue to treat suffering, possibly refer to another provider if allowed by law. They rarely ask you to endorse PAS directly.

What is allowed and sometimes tested:

Aggressive symptom control, even if it may shorten life (doctrine of double effect).

Example pattern: “You increase morphine for severe dyspnea. This may hasten death by respiratory depression.”

Acceptable if:- Primary intention is symptom relief.

- Dose is proportionate to symptom severity.

Palliative sedation for refractory suffering in a terminally ill patient who is imminently dying, when all other options have failed.

Again, the intention is relief, not death.

So if the answer choices include:

- “Increase opioid dose to relieve dyspnea” vs “refuse more morphine because it may hasten death”

You choose symptom relief.

Withholding vs Withdrawing: Boards Want You to Be Ethically Mature

They love this line:

Withholding life-sustaining treatment and withdrawing it are ethically and legally equivalent.

So:

- Not starting dialysis

- Stopping dialysis already started

Both are allowed if consistent with patient’s wishes or best-interest standards.

Common stem:

- “Family says it would be ‘killing him’ to stop the ventilator but is okay with not doing ‘anything new’.”

The educational answer: clarify that both actions are ethically the same; you are not obligated to continue interventions the patient would not want.

Again, they will tempt you with emotional words. Ignore. Apply the equivalence principle.

Minors, Parents, and Emancipation

End-of-life and capacity questions with minors have their own traps.

Baseline rule:

- Parents/guardians usually decide for minors.

- BUT—not absolute. You must still protect the child’s best interest.

Patterns you will see:

Parent refuses life-saving treatment for minor (e.g., blood transfusion for a 6-year-old with acute hemorrhage), based on religious beliefs.

- Exam answer: Obtain a court order and provide life-saving treatment.

The child’s right to life and health overrides parental refusal in emergencies.

- Exam answer: Obtain a court order and provide life-saving treatment.

Mature minor refusing treatment:

- Some states recognize mature minor doctrine; boards use this selectively.

- More commonly, for high-risk or life-saving treatment, you still involve parents and potentially the court if needed.

Emancipated minor (married, parent themselves, living independently with own income, or legally emancipated):

- They function as adults for consent and refusal. Their wishes override their parents.

Boards also test limited confidentiality:

- Adolescents can usually consent for STIs, contraception, pregnancy care, substance use treatment, etc. independently.

- But end-of-life decisions for minors still often involve parents and courts.

“Futile” Treatment and When You Can Say No

There is a very specific exam pattern on medical futility.

Futility = treatment that will not achieve the patient’s articulated goal in any medically meaningful way.

Example:

- Family demands CPR on a patient in multi-organ failure with no chance of survival to discharge or even short-term meaningful recovery, and all consultants agree.

Boards do not want you performing harmful, non-beneficial treatment just because relatives say so.

Patterned answer:

- Explain that the requested intervention is medically futile and will not be performed.

- Offer alternative focus on comfort and support.

- Ethics committee consultation can be appropriate.

- You do not have to offer every intervention a family demands if it provides no benefit.

The key is: you must communicate, explain, and not abandon. But you are not a vending machine.

Communication Patterns Boards Reward

Ethics questions often give you 5 answer choices that are all “words,” and you are supposed to pick the best phrase. This is where people overthink.

Winning patterns:

- Start with understanding and empathy. “I can see how difficult this is for you” beats “Hospital policy says…”

- Clarify patient’s goals before discussing specific treatments: “Help me understand what your mother would consider a meaningful quality of life.”

- Use patient-focused language: “What would your father have wanted in this situation?” instead of “What do you want us to do?”

Avoid:

- Throwaway reassurances: “There is nothing more we can do.”

(Wrong. There is always something to do for comfort and support.) - Abandonment: “We will sign you out to hospice and end our involvement.”

- Blame: “You signed the DNR, this is what you chose.”

If there is a choice that explicitly mentions exploring the patient’s values, clarifying understanding, or involving palliative care early—that is usually the right answer.

High-Yield Patterns in Question Stems

Let me give you a few archetypes. You will recognize them almost immediately once you know what they are doing.

1. The “Capacitated Refusal of Life-Saving Treatment”

- Patient: lucid, repeats back risks, understands will die without treatment.

- Family: begging for you to treat anyway.

- Question: “Best next step?”

Correct pattern: Respect the patient’s autonomous refusal, provide comfort, involve palliative care. Family distress does not override capacity.

2. The “Ambiguous DNR and Aggressive Treatment”

- DNR on chart, no other limits documented.

- Acute, reversible issue (e.g., pneumonia, GI bleed).

- Team hesitating: “But she is DNR…”

Correct pattern: Treat aggressively as indicated. DNR does not mean “do not treat.” Only affects resuscitation after arrest, unless expanded.

3. The “Surrogate Conflict with Advance Directive”

- Clear written directive: no ventilators, no feeding tubes, comfort-only.

- Surrogate: “Ignore that, I want everything done.”

Correct pattern: Follow the advance directive that reflects patient’s prior autonomous choice. Explain to surrogate their role is to honor those wishes, not replace them.

4. The “Capacity Question with Psychiatric Diagnosis”

- Schizophrenia, bipolar, dementia label in chart.

- Patient currently calm, oriented, repeating risks and benefits, giving clear preference.

Correct pattern: Treat them as having capacity for that decision. Do not automatically label them incapable because of diagnosis alone.

5. The “Minor and Life-Threatening Refusal by Parents”

- Under 18, life-threatening but treatable condition.

- Parents refuse, usually due to religion.

Correct pattern: Involve legal authorities / court to provide life-saving care despite parental refusal.

Quick Comparative Table: Typical “Trick” Choices and The Right Move

| Scenario | Wrong Tempting Answer | Correct Pattern Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Competent adult refuses dialysis | Seek court order to mandate treatment | Respect refusal after capacity assessment |

| DNR with sepsis | Withhold antibiotics and ICU care | Provide full treatment, DNR only affects CPR |

| Proxy vs written directive conflict | Follow proxy’s emotional request | Follow written advance directive |

| No clear surrogate, unstable patient | Wait for family to arrive before treating | Provide emergency, life-saving treatment |

| Parent refuses transfusion for child | Respect parental religious beliefs | Seek court order and transfuse |

If You Remember Nothing Else

Three points.

Capacity is clinical, task-specific, and yours to assess. If a patient with capacity refuses or accepts treatment after clear discussion, you respect it, even if it leads to death.

The patient’s own wishes—current if capacitated, or prior documented (advance directive / POLST) if not—outrank everyone else. Family distress does not override clear patient preferences.

Withholding vs withdrawing, symptom relief that may shorten life, and DNR vs “no treatment” are areas where boards expect you to be ethically grown-up: respect autonomy, minimize suffering, and avoid non-beneficial interventions, even under pressure.

You learn these patterns once. They will pay you back every time you see an ethics stem—on the exam and at 2:17 a.m. on night float.