What if the reason you feel like you’re failing residency mentally isn’t because you’re not smart enough, but because you believe a myth that no one bothers to challenge out loud?

Let me be blunt: the “genius resident” you think you’re competing against does not exist. And the idea that you need near‑photographic recall of every obscure fact to pass your in‑training exam or boards is not just wrong — it’s actively screwing up how you study, how you sleep, and how you feel about your career.

Let’s tear that apart properly.

The Genius Resident Myth (And Why It’s Garbage)

You know the character:

The senior who “just remembers everything from med school.”

The co-resident who shrugs and says, “Oh yeah, that’s obviously Loffler endocarditis,” while your brain is still trying to spell eosinophil.

Here’s the quiet thing no one says during rounds: almost nobody has the kind of raw, stable, instant recall you think is normal for good residents. What you’re seeing is:

- Repetition over years

- Pattern recognition

- Strategic guessing

- Selective memory (they show you what they know and hide what they don’t)

Board and in‑training exam performance is not a measure of who has the best memory on earth. It’s a measure of who has:

- Enough core knowledge

- An accurate sense of what actually gets tested

- Basic test-taking skills

- A minimally functioning brain on test day (sleep, anxiety under control, etc.)

The “Genius Myth” survives for three reasons:

- Residents rarely admit how much they don’t know. Nobody is going to volunteer, “I missed 40% of my practice questions last week.”

- Attendings sometimes perform amnesia about their own training. The same person who pimped you today probably once froze on rounds over the difference between prerenal vs intrinsic AKI — and then conveniently forgot that part.

- You only see the highlight reel. You see the confident answer, not the 15 questions they got wrong on UWorld that morning.

The data backs this up: high pass rates across specialties with wide variability in learning styles, backgrounds, and yes, memory quality. If “genius-level recall” were actually required, the pass rates and progression rates through residency would be dramatically lower than they are.

What Board Exams Actually Test (Not What You Think)

Boards are annoying. Sometimes pedantic. Occasionally absurd. But they’re not random.

They’re probabilistic exams. They test what’s common, dangerous, and guideline-driven — over and over — with a layer of zebras sprinkled on top to separate the top scorers.

Look at any major Qbank for your specialty and you’ll see the pattern:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Common high-yield | 35 |

| Dangerous/emergent | 20 |

| Management guidelines | 25 |

| Rare zebras | 10 |

| Miscellaneous | 10 |

Notice something? The exam is not:

- 80% obscure gene mutations

- 70% “name-the-eponym-you-saw-once”

- Pure random trivia

Yet that’s how many residents study — as if every rare parasite, every weird vasculitis variant, and every orphan disease must be memorized cold.

What actually moves your score:

- Recognizing pattern-based vignettes quickly

- Knowing first-line vs second-line management

- Distinguishing emergent vs outpatient situations

- Avoiding trap answers that are almost right

None of this requires superhuman recall. It requires solid familiarity with repeated patterns. That’s different.

Evidence Against the “Perfect Recall or Fail” Story

Let’s walk through what actually predicts passing.

1. Question Bank Performance > Raw Memory

Programs track this. Quietly. I’ve sat in meetings where faculty review resident performance on Qbanks and in-training exams. Nobody is asking, “Does this resident have perfect recall on rounds?” They’re asking:

- Are they consistently doing questions?

- Is their percent correct trending upward over time?

- Do they improve when they review explanations, or are they stuck?

| Category | Resident A (passes boards) | Resident B (plateaus) |

|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | 48 | 50 |

| Month 3 | 55 | 52 |

| Month 6 | 62 | 54 |

| Month 9 | 68 | 55 |

| Month 12 | 72 | 56 |

Resident A doesn’t start out as a genius. They start mediocre and steadily climb. That’s what predicts passing.

I’ve seen residents with “average” memory — they forget labs, they mix up drug names — pass comfortably because they did 3,000+ questions intelligently. I’ve also seen people with scary-good recall flame out because they did almost no practice questions and assumed memory alone would carry them.

2. Time-in-training Matters More Than You Think

There’s a well-known phenomenon: most people do better on boards closer to the end of residency than at the beginning, even if they don’t do dramatic extra studying.

Why? Because:

- You see the same diseases again and again

- You sit in on the same management discussions every day

- You’re constantly primed to think in board-style format (“What’s the next best step?”)

Experience compresses into patterns. Pattern recognition saves your memory from having to hold 10,000 isolated facts.

3. The Pass Rates Don’t Support the Myth

Look at many AB board exams: pass rates often range between ~85–95% for first-time takers in most core specialties. That’s not a “genius-only” barrier. That’s a “reasonably prepared, not-disaster-level” barrier.

If the test really required near-perfect recall:

- You’d see far more people failing repeatedly

- There’d be massive attrition from programs

- Rumors of 40–50% failure rates would be everywhere (they’re not)

Residents who fail often have one or more of these issues:

- Did not do enough practice questions

- Serious personal crisis, burnout, or untreated depression/anxiety

- Catastrophic test anxiety

- Completely fragmented study approach

Notice what’s missing from that list: “simply did not have genius-level memory.”

What Actually Works When Your Memory Isn’t Perfect

Let’s talk strategy instead of fantasy.

Perfect recall is not required. What you need is reliable recall of the right stuff, plus damage control for what you inevitably forget.

Here’s the unglamorous, effective toolkit.

1. Core-First, Trivia-Last

Your brain has limited bandwidth, especially when you’re post-call, hungry, and someone just yelled about a missing consent form.

You cannot waste that capacity memorizing fourth-line drugs for some metabolic disease that shows up once every 300 questions.

You prioritize:

- Life-threatening and common things

- First-line diagnostics and treatments

- “Next best step” logic

- Major guidelines (the broad strokes, not every number)

Think: are you more likely to be tested on the exact SNP for Factor V Leiden, or the clinical pattern of a 35-year-old with unexplained DVT and family history?

Exactly.

2. Spaced Repetition: Cheating the Memory System (Legally)

Spaced repetition (Anki, etc.) is not for “gunners.” It’s for people who admit their memory is human.

The point isn’t to memorize every sentence from a textbook. It’s to:

- Capture high-yield errors from your question bank

- Turn them into short, targeted cards

- See them again at progressively longer intervals so they stick

Not 10,000 cards. That’s performative. You want 500–2,000 brutally efficient ones built off your actual mistakes.

3. Question-Driven Learning, Not Textbook Worship

Many residents secretly believe this: “If I just read everything once or twice, I’ll know it.”

No you won’t. Not with call, clinic, consults, and the pager going off every 8 minutes.

The higher-yield loop is:

- Do questions in blocks (timed, exam mode)

- Review EVERY explanation — right and wrong

- Extract 1–3 key concepts per block into notes or flashcards

- See those weak areas again in a week

You learn the board’s language and patterns, not individual facts in isolation.

And yes, that means your study time will look “messy.” You’ll be jumping between AFib, nephrotic syndrome, and sarcoid. That is exactly how the exam feels.

4. Test-Taking Strategy Is Not Optional

I’ve seen residents with “enough” knowledge lose 10–15 points purely from technique errors.

Fixable stuff like:

- Spending too long on early questions and rushing late ones

- Changing answers constantly based on anxiety rather than reasoning

- Falling for classic distractors that sound impressive but don’t answer the question

You don’t fix that by memorizing more facts. You fix it by:

- Regular timed blocks

- Reviewing not just why the right answer is right, but why the wrong ones are wrong

- Practicing guessing rationally when you’re unsure

“Perfect recall or fail” people completely ignore this domain. Then are shocked when they underperform despite “knowing so much.”

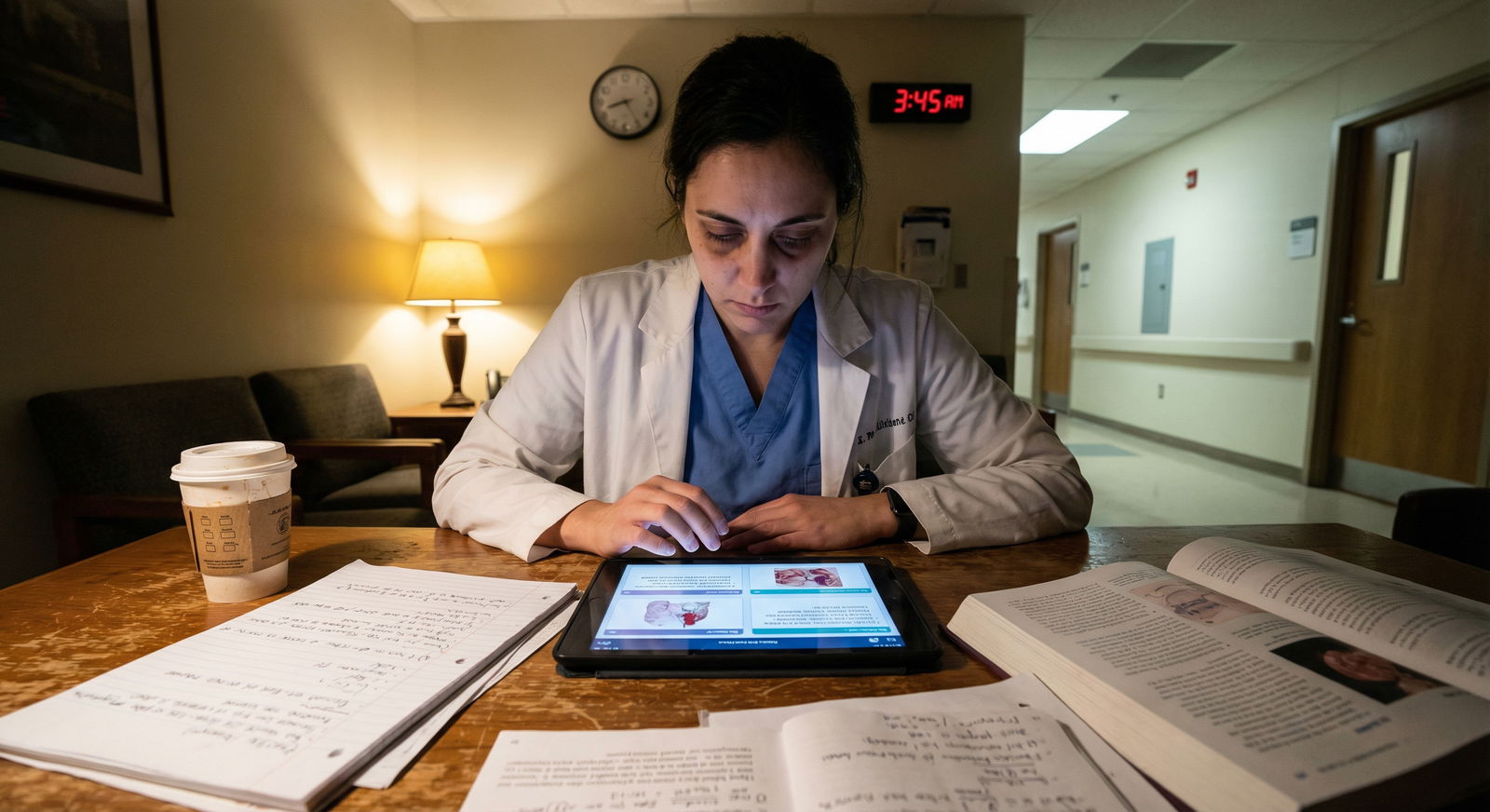

The Role of Sleep, Stress, and Working Reality

Here’s the dirty secret: a sleep-deprived brain with “great memory” performs worse than a rested brain with “decent memory.” Every time.

You already know this from call days when you can’t remember basic drug doses you knew cold the day before.

Yet residents routinely:

- Try to study long hours post-call

- Cut sleep to grind more questions

- Treat anxiety like a character flaw instead of a performance limiter

This is not motivational poster talk. It’s neurobiology.

| Factor | Cramming Week Before | Consistent 3–6 Months |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 4–5 hours/night | 6–7 hours/night |

| Question Volume | High, inefficient | Moderate, consistent |

| Retention | Poor | Good |

| Stress Level | Extreme | Fluctuating but lower |

| Exam-Day Clarity | Foggy | Functional |

If you’re repeatedly:

- Forgetting things you know you know

- Blank during questions then remember later

- Re-reading the same paragraph with nothing sticking

That’s not proof your memory is broken. That’s your brain quietly yelling: “Stop treating me like a hard drive and more like a living organ.”

You pass boards more from months of tolerable, repeatable work than from a heroic final month of suffering.

Real-World Residents, Not Fantasy Characters

Let me sketch a couple of very real archetypes I’ve seen.

Resident 1: The Apparent Genius, Secretly Chaotic

- Crushes pimp questions

- Remembered ridiculous minutiae from M2

- Barely does any structured questions

- Reads random chapters before bed “for fun”

- Underperforms or barely passes boards because their studying is scattered and misaligned with the exam

Resident 2: The Quiet Grinder

- Starts Qbank early in PGY-2 or late PGY-1

- Steadily does 10–20 questions most days

- Makes simple notes or cards on repeated misses

- Feels “average” compared with flashier co-residents

- Walks into boards with solid pattern recognition, finishes comfortably, passes by a clear margin

Guess which one programs trust over time? The grinder. The one who built reliable, not perfect, recall of the right material.

You don’t need to become some machine who never forgets. You need to become someone who:

- Sees the same important ideas enough times

- Practices under exam-like conditions

- Manages basic human needs enough that your brain can show up on game day

That’s not genius. That’s system.

How To Rethink Your Own “I’m Not Smart Enough” Narrative

If you’ve ever told yourself any of this:

- “I just don’t retain things like other people.”

- “I’m not one of the naturally smart ones.”

- “My memory has gotten worse since med school, something’s wrong with me.”

Let me reframe that.

You’re comparing:

- Your internal experience of forgetting

to - Other people’s external performance highlights

Of course you lose that comparison. You know every mental blank you’ve had. You see maybe 5% of theirs.

You are not required to remember everything, all the time, under all conditions, to be board-pass ready. You are required to:

- Remember the right subset reliably

- Function under imperfect conditions

- Have enough strategy to cover for the gaps

Stop grading yourself against an imaginary standard no one actually meets.

FAQs

1. What if my in-training exam score was low — does that mean I’m doomed?

No. ITE scores are a signal, not a verdict. They tell you two things: where you are now and where your biggest holes are. Residents with low PGY-1 or even PGY-2 ITEs routinely pass boards after 6–12 months of consistent, question-driven, focused studying. A low score is a mirror, not a sentence.

2. How many questions do I actually need to do to be “safe” for boards?

There’s no magic number, but for most core specialties, residents who complete one full major Qbank (2,000–3,000 questions) thoughtfully — with review and note-taking — are in a very strong position. A second Qbank or a partial second one can help, but doing one thoroughly beats skimming two or three.

3. What if I genuinely feel like my memory has tanked since starting residency?

That’s common and usually reflects chronic sleep debt, stress, and cognitive overload, not an intrinsic loss of ability. Before you assume something is fundamentally wrong, fix what you can: sleep slightly more, cut low-yield studying, switch to active question-based learning, and address anxiety or depression if present. If you’re still experiencing major memory issues in basic daily tasks, then discuss it with a physician — but don’t diagnose yourself as “not smart enough for medicine” based on residency brain fog.

Key takeaways:

You don’t need perfect recall to pass; you need reliable recall of high-yield patterns.

Consistent, question-based, pattern-focused studying beats “genius memory” every single time.