Most IMGs waste their leadership experience by hiding it in a single bullet point. That is a mistake. A big one.

If you led anything meaningful in your home country—student council, quality improvement, national camp, NGO clinic—ERAS will either convert it into a strategic asset or bury it so deep it might as well not exist. The difference is how you structure, label, and integrate those roles across the entire application.

Let me break this down specifically, because this is where a lot of strong IMGs quietly lose the game.

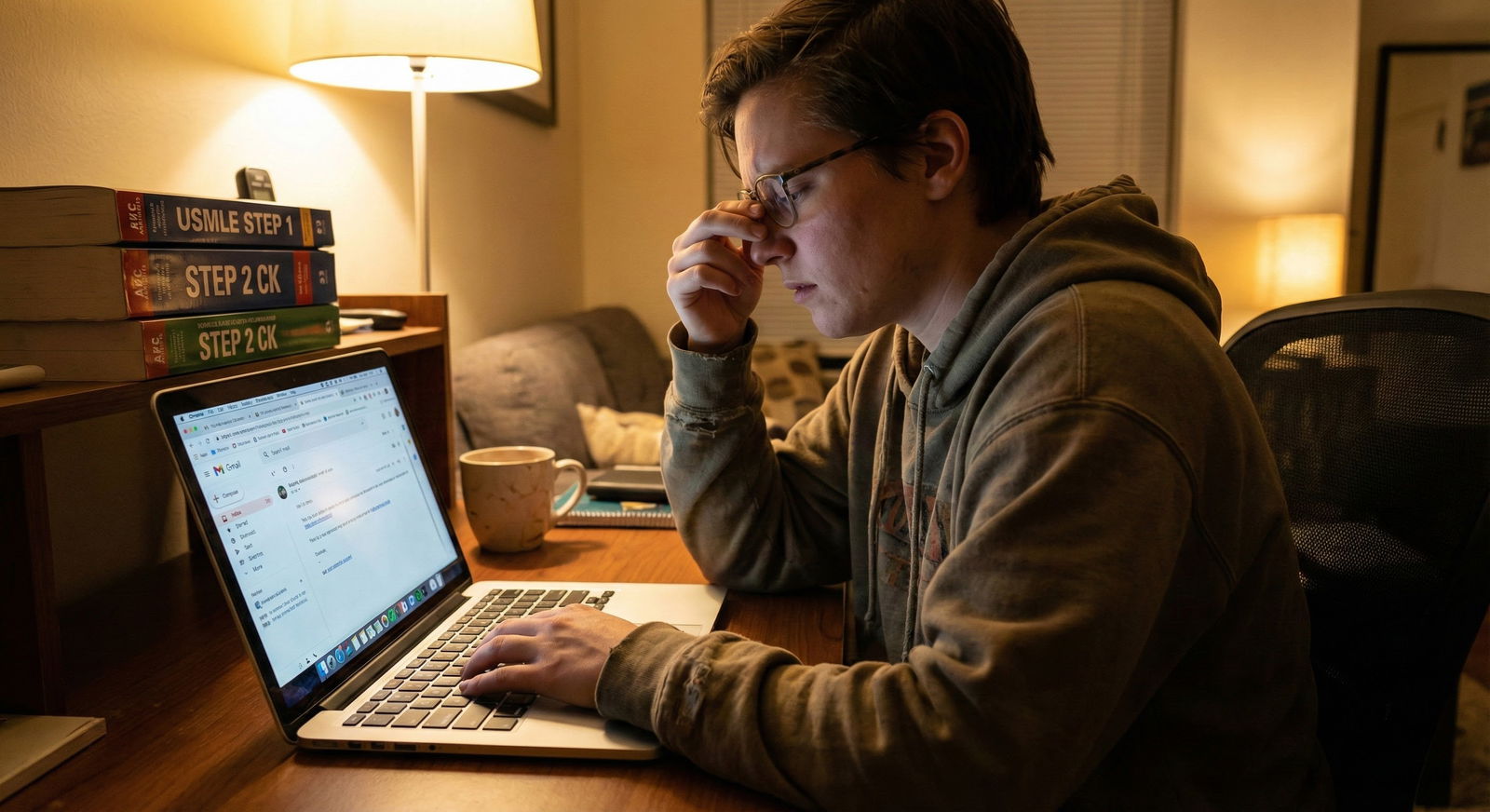

1. The brutal truth: how U.S. programs actually see IMG leadership

Residency programs do not automatically respect your “President, XYZ Society” from outside the U.S. They have three immediate questions in their heads:

- Was this real responsibility or just a vanity title?

- Is anything you did there transferable to an ACGME training environment?

- Can I trust this applicant to function as a team leader here, not just back home?

If you do not answer those questions clearly in ERAS, they default to: “Probably minor. Not comparable to our stuff. Move on.”

That is why generic bullets like:

- “Organized conferences and workshops”

- “Actively participated in student union meetings”

- “Was responsible for many activities”

are useless. They tell an American PD nothing.

Your job is to translate home‑country leadership into ACGME language: systems, teams, measurable outcomes, education, QI, patient safety, advocacy. Same experience, different packaging.

2. Where leadership actually lives in ERAS (and how to place it)

Your leadership story is not one line in “Volunteer Experiences.” It is a theme that must echo across multiple sections.

Core ERAS sections you must use

You should be thinking about leadership in at least these areas:

- Experiences (Work, Research, Volunteer)

- Education (especially if leadership was tied to school roles)

- Publications / Presentations (if your leadership involved academic output)

- Personal Statement

- Letters of Recommendation (from those who saw you in leadership)

- MSPE / Dean’s Letter (if your school acknowledges leadership roles)

Let me be explicit about placement.

2.1 Experiences section: the backbone

Most home‑country leadership should go here. Typical categories:

- Volunteer: student organizations, free clinics, outreach projects, NGOs

- Work: salaried or formal hospital/clinic leadership roles

- Research: if you led a team/project, even informally

Key rule:

If you had sustained responsibility, decision-making, and people management, treat it as its own Experience entry, not a sub‑bullet under some generic “Medical School Activities.”

For example:

- Bad: “Medical School Activities – Member, Student Council; Led Workshops; Organized Health Camps”

- Better:

- “President, Medical Student Association – [University, Country]”

- “Coordinator, Community Hypertension Screening Project – [City, Country]”

2.2 Education section: title signaling

If your leadership role was formally recognized by the university (e.g., “Class Representative”, “Student Union Executive”, “Chief Intern”), it can be briefly reflected in Education, but only if the field allows and it looks clean. Do not cram it into degree names.

Instead, your dean’s letter/MSPE and transcripts sometimes have an “Activities / Distinctions” portion. Make sure your school knows these roles matter for U.S. residency so they actually write them.

2.3 Personal statement: selective amplification

You do not list every leadership position here. You choose one or two roles that:

- Directly relate to your specialty interest

- Show growth in responsibility

- Led to specific, tangible outcomes

You then connect that to why you are prepared to function in a U.S. residency team structure.

Hold that thought; I will show you exact phrasing later.

2.4 Letters of recommendation: external validators

A home‑country leadership role becomes 10x more credible if someone else describes it with concrete detail.

You want at least one letter writer who can say things like:

“As President of the Medical Student Association, Dr. X coordinated over 300 students across four campuses, redesigned our peer‑teaching structure, and successfully advocated for updated clinical skills training schedules. I witnessed these efforts directly over two academic years.”

Programs trust that much more than your own self‑description.

3. Choosing which roles to highlight (and which to quietly drop)

Not all leadership is created equal. Some roles help you; some just add noise.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical/QI Leadership | 95 |

| Education/Teaching Leadership | 85 |

| National/Regional Roles | 80 |

| Purely Social Clubs | 40 |

| Short-Term Event Committees | 30 |

Here is how I rank IMGs’ leadership experience by impact on U.S. PDs:

Clinical or quality-improvement leadership

- Led a clinic, coordinated outpatient services, managed process changes

- Example: “Clinic Coordinator, Weekly Diabetic Foot Clinic – Reduced no‑show rate from 40% to 22% in one year”

Educational leadership

- Structured teaching for juniors, designed curricula, ran review courses

- Example: “Founder, Resident‑Led ECG Boot Camp – Trained 80+ junior students”

Organizational / national or regional roles

- National student society boards, national conference organizing committees

- Example: “National Vice President, IFMSA [Country] – Oversaw 12 local committees”

Community outreach and advocacy with clear outcomes

- Repeated camps, policy campaigns, structured public health projects

Low‑impact or vague social roles

- “Cultural secretary”, one‑time fest committees, WhatsApp group admin nonsense

If you have 10 leadership roles, do not try to list all 10. Curate:

- 3–5 high‑yield roles as full ERAS entries

- Others, if you must mention them, as short bullets within a single “Other Activities” entry

4. The anatomy of a strong ERAS leadership entry for IMGs

This is where most IMGs get sloppy. They either over‑inflate (“Managed 2000 patients per month alone”) or under‑sell (“Helped with events”).

You need disciplined structure.

4.1 Position title: translate, do not copy-paste

Your official title might be “General Secretary, Student Cultural Committee.” That means very little to an American PD.

Translate it to something functionally equivalent and understandable:

- “President” or “Chair” if you led the whole thing

- “Coordinator” if you ran operations

- “Director” if you designed and oversaw a structured program

- “Chief Intern / Chief House Officer” if that is accepted terminology in your country

Examples:

Instead of: “General Secretary, Student Cultural Committee”

Use: “Coordinator, Medical School Events Committee (Elected Position)”Instead of: “Unit Incharge, Diabetic Clinic”

Use: “Clinic Coordinator, Diabetes Outpatient Service”

You can include the original title in parentheses in the description if there is cultural nuance.

4.2 Organization: anchor it clearly

Do not write:

- “College”

- “General Hospital”

Write:

- “XYZ University Faculty of Medicine, [City, Country]”

- “ABC Teaching Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine, [City, Country]”

Aligns with the way American institutions name themselves.

4.3 Dates and time commitment: look real

Programs are used to inflated claims. Do not help their skepticism.

- Use realistic hours/week. If you write “40 hours/week” for an unpaid student organization, no one believes you.

- Be consistent with overlap. If you were doing full‑time internship plus “30 hours/week leadership” at the same time, it looks impossible.

Typical ranges that make sense:

- Major student leadership: 5–15 hrs/week

- Clinic coordinator during internship: 3–8 hrs/week

- National student society roles: 5–10 hrs/week

4.4 Description: 3–6 bullets with outcomes, not tasks

Structure every bullet around:

[Action verb] + [what you did] + [scale] + [measurable or at least concrete outcome]

Weak:

- “Organized health camps in rural areas.”

- “Responsible for student welfare.”

Stronger:

- “Planned and led 6 rural hypertension and diabetes screening camps over 12 months, reaching approximately 1,200 adults; identified 18% with previously undiagnosed hypertension and 11% with uncontrolled diabetes.”

- “Established a peer‑mentoring system for first‑year medical students, matching 110 juniors to 55 senior mentors and creating referral pathways for academic and mental‑health support.”

When you cannot get a perfect number, at least get approximate scale:

- “Led a core team of 8 volunteers and coordinated ~40 rotating medical students…”

- “Secured small‑grant funding (equivalent to USD 1,500) for project expansion…”

4.5 Link to competency language

ACGME core competencies matter. You do not have to recite them, but you should echo their spirit:

- Systems‑based practice: “Redesigned triage flow, reduced average waiting time…”

- Practice‑based learning: “Collected and reviewed data, adjusted process…”

- Interpersonal and communication skills: “Mediated conflicts between…”

- Professionalism: “Responsible for maintaining confidentiality, ethical oversight…”

- Leadership & teamwork (sometimes framed under Interprofessional skills): “Facilitated weekly team huddles…”

Embed this in the description naturally.

Example bullet:

“Led weekly planning meetings with interdisciplinary team (nursing, social work, student volunteers) to coordinate follow‑up for high‑risk patients, emphasizing clear role assignment and closed‑loop communication.”

You are basically saying: “I already work the way your residents are supposed to work.”

5. Crafting the personal statement around leadership without sounding arrogant

Most IMGs either avoid their leadership entirely in the PS or write a self‑promotion essay. Both are mistakes.

Your leadership should feed three elements:

- Motivation for your specialty

- Evidence that you function above the minimum level

- Proof that you understand systems and teams, not just individual grit

5.1 One anchor story, not your whole CV

Pick one leadership experience that naturally connects to your specialty.

- Internal medicine: leading chronic disease clinics, QI projects, teaching ECGs

- Pediatrics: vaccination drives, school health programs

- Psychiatry: student mental‑health initiatives

- FM/Community: community camps, longitudinal outreach

Write it like a narrative, but end with clear reflection and link to residency.

Example (for an IMG applying to IM):

“During my final year, I was elected coordinator of a weekly diabetes clinic at our teaching hospital. At first, the role sounded administrative—compile the list, manage the queue, sign forms. It changed the day I sat with our nurses and realized that nearly half our patients were missing follow‑up visits. Over the next six months, I worked with our team to redesign the appointment system, introduce reminder phone calls, and create a simple logbook for missed visits. By the end of the year, our no‑show rate had dropped from ‘almost every other patient’ to about one in five. More importantly, I began to see chronic disease care as a system rather than a series of individual visits. That perspective is what draws me to Internal Medicine in the U.S., where I hope to contribute to team‑based, long‑term management of complex patients.”

Notice:

- Clear role

- Team involvement

- Outcome

- Reflection tied to specialty

5.2 Avoid the “I was the hero” trap

If every sentence centers on you “solving” everything, PDs roll their eyes.

Use language like:

- “We developed… I coordinated…”

- “Working with our nurses and junior students…”

- “Under the supervision of Dr. X, I…”

This still credits you, but shows you can function in a hierarchy—crucial in residency.

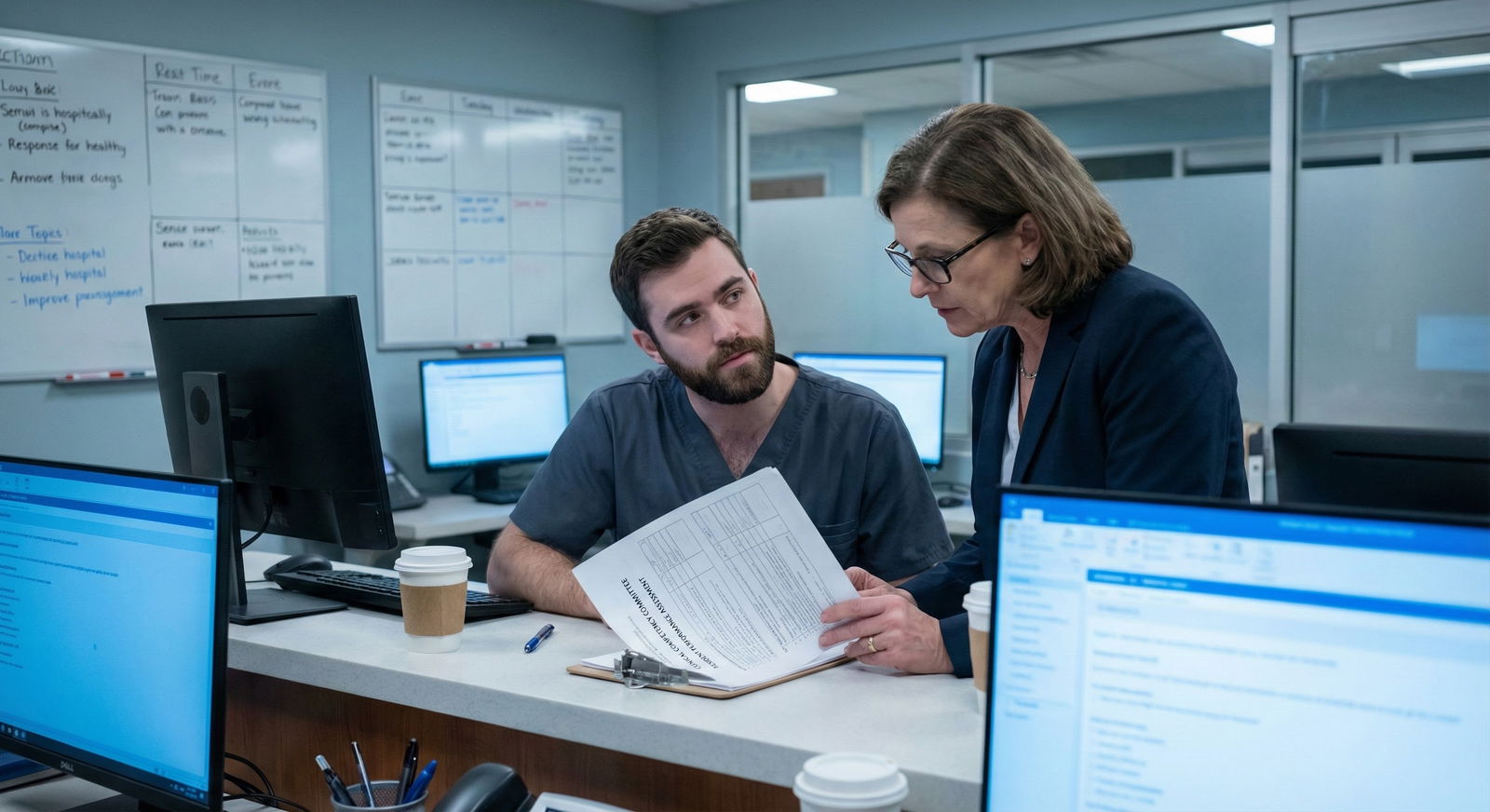

6. Getting letters that prove your leadership (not just repeat it)

Weak home‑country letters say:

- “X was a member of our committee. He was hardworking, punctual, and sincere.”

Strong letters say:

- “X independently coordinated…”

- “I relied on X to…”

- “X showed maturity beyond level by…”

You want letter writers who saw you:

- Making decisions

- Handling conflict or resource limitations

- Teaching juniors

- Following through over time

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Identify real leadership role |

| Step 2 | Choose supervisor who observed you |

| Step 3 | Provide them with summary + outcomes |

| Step 4 | Meet to discuss key examples |

| Step 5 | Letter emphasizes responsibility, impact, and professionalism |

6.1 Brief your letter writer properly

Do not just say, “Please mention my leadership.” Hand them something usable:

- 1‑page summary of:

- Your role title and dates

- 3–5 concrete things you did

- Any numbers/outcomes you have

- How this relates to your chosen specialty

This is not “writing your own letter.” It is giving your referee memory and structure.

Sample talking points you can give them (verbatim is fine):

- “I would be very grateful if you could particularly comment on my role as [position] where I coordinated [describe] and any examples of how I worked with the team, handled responsibility, or showed initiative.”

If they pick up even half of this, the letter will be far stronger than the average generic “good student” letter.

7. Addressing the “home‑country vs U.S. system” gap directly

PDs sometimes quietly wonder: “Yes, but can this person adapt to our system?”

You can and should preempt that concern.

7.1 Translate constraints, not complain about them

If you worked with limited resources, frame it professionally:

Weak:

- “We had no resources and it was very difficult and unfair.”

Stronger:

“In our setting, formal quality‑improvement infrastructure was limited, so we created simple manual tracking tools and used weekly staff huddles to implement small changes.”

Shows adaptability, not bitterness.

7.2 Show awareness of differences

If you have U.S. clinical experience, connect your leadership mindset to what you saw there:

“During my observership at [U.S. program], I recognized many parallels between the small‑scale system changes we implemented in my home clinic and the structured QI initiatives led by residents. I look forward to refining those skills in a more formal framework.”

Even without U.S.CE, you can mention:

- Your interest in QI projects

- Desire to learn EMR‑based workflows

- Openness to different hierarchies and interprofessional team structures

8. Common mistakes IMGs make with leadership in ERAS

I have seen these patterns repeatedly. They hurt your application more than silence.

| Mistake | Better Approach |

|---|---|

| Listing 8+ minor roles | Select 3–5 high-impact roles with depth |

| Vague descriptions ("helped organize") | Specific outcomes and scale |

| Inflated titles ("Director" for a student) | Translated but realistic titles ("Coordinator", "President") |

| Unrealistic hours/week | Conservative, believable time estimates |

| No connection to specialty choice | Explicitly link at least one role to chosen field |

Let us be concrete.

8.1 “Laundry list” CV syndrome

Ten roles, zero depth. PDs skim and retain nothing.

Fix:

Limit full entries. For the rest, group them:

- “Other Student Activities and Committees” – then in description, list brief phrases without pretending each was huge.

8.2 Over‑dramatizing

“Managed all clinical care for 5000 patients per year.”

No, you did not. At least not alone.

Refine:

“Participated as part of a team providing care to approximately 5,000 outpatient visits annually; within this, I specifically coordinated follow‑up for patients with uncontrolled diabetes.”

Shows you know where your responsibility started and ended.

8.3 Ignoring chronology

PDs like to see progression:

- Member → Coordinator → President

- Volunteer → Organizer → Founder

Make sure the experiences are ordered clearly by date, and if there is progression in the same organization, make that explicit:

“Elected as class representative in 3rd year; subsequently elected as overall Student Association President in final year.”

This signals reliability and peer trust, which are gold.

9. Specialty‑specific angles: tailoring your leadership story

You do not sell the same leadership story to Psychiatry and General Surgery. Same history, different emphasis.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 90 |

| Family Medicine | 85 |

| Pediatrics | 80 |

| Psychiatry | 75 |

| Surgery | 70 |

9.1 Internal Medicine / FM

Lean on:

- Chronic disease clinics

- Longitudinal community follow‑up

- QI in outpatient workflows

- Patient education initiatives

Language: “systems‑based practice”, “continuity of care”, “chronic disease management.”

9.2 Pediatrics

Lean on:

- School health programs

- Vaccination campaigns

- Parent education sessions

- Child advocacy or malnutrition programs

Mention child‑specific communication and multidisciplinary coordination (teachers, social workers).

9.3 Psychiatry

Lean on:

- Mental health awareness campaigns

- Peer support or counseling programs

- Suicide prevention initiatives

- Substance‑use awareness projects

Be careful with boundaries: emphasize supervision, ethical handling, and referral pathways rather than portraying yourself as a solo therapist.

9.4 Surgery

Leadership that shows:

- Operating room or procedure scheduling

- Surgical skills workshops you organized

- Trauma call coordination

- Instrument/sterility process improvements

Highlight attention to detail, team coordination in acute settings, and procedural teaching.

9.5 Pathology, Radiology, Anesthesia, etc.

Focus on:

- Academic teaching programs

- Lab or workflow organization

- Protocol development

- Interdepartmental communication improvements

You get the pattern: pick the angle that resonates with what that field values.

10. Putting it all together: a mini‑case

Let me give you a compact before/after.

10.1 Raw reality (what most IMGs start with)

- “General Secretary, Student Union”

- “Organized events and sports”

- “Participated in health camps”

- “In charge of clinic”

Scattered across ERAS, no structure.

10.2 Strategic version for an IMG applying to Internal Medicine

Experiences:

Position: President, Medical Student Association (Elected)

Organization: XYZ University Faculty of Medicine, [Country]

Description (bulleted):- Led elected executive team of 10 and represented ~650 medical students to faculty leadership regarding curriculum, clinical rotation scheduling, and exam logistics.

- Co‑designed and implemented a peer‑tutoring program in core clinical subjects (Internal Medicine, Surgery, Pediatrics), pairing 120 junior students with 40 volunteer tutors; program sustained for 3 consecutive academic years.

- Collaborated with hospital administration to adjust intern coverage during exam periods, improving adherence to duty‑hour policies while maintaining ward coverage.

Position: Clinic Coordinator, Diabetes Outpatient Service

Organization: ABC Teaching Hospital, [Country]

Description:- Coordinated weekly diabetes clinic serving ~60–80 patients per session under supervision of an attending endocrinologist.

- Introduced a simple paper‑based tracking sheet for missed appointments and organized reminder calls, contributing to a reduction in observed no‑show rates from approximately 40% to around 20% over one year.

- Led brief education sessions for rotating medical students about clinic workflow, patient education priorities, and documentation standards.

Personal Statement:

- Anchor story from the diabetes clinic, linking leadership to interest in chronic disease and systems‑based care.

LOR:

- One letter from endocrinologist describing the clinic coordination and reliability.

- One letter from faculty advisor of the Student Association confirming scope and role.

Now the same real experiences are suddenly highly legible to a U.S. PD.

FAQ (exactly 5 questions)

1. My leadership roles were all in pre‑clinical years. Are they still worth highlighting for ERAS?

Yes, if they were substantial and show clear responsibility, but you must be selective. A major role like “President of the Medical Student Association” in second year is still meaningful in residency applications, especially if it had academic or organizational impact. However, balance it with more recent clinical‑related experiences. If all your leadership is early and nothing later, PDs may question whether you maintained that trajectory. In that case, emphasize any informal leadership during internship or clinical rotations—teaching juniors, coordinating small projects, even if those were not formally titled.

2. I was “Class Representative” every year, but it felt routine. Should I list it?

Only if the role involved more than relaying exam schedules on WhatsApp. If you actually mediated between faculty and students, organized academic support, or contributed to policy changes, then yes—present one consolidated “Class Representative (Multiple Terms)” entry and describe the most impactful responsibilities. If the role was purely administrative with no substantive initiatives, mention it briefly in a grouped activities entry or skip it. Weak leadership entries dilute the effect of your stronger ones.

3. Can I combine a clinical role and leadership in the same ERAS entry?

You can, but do it carefully. If you were an intern in a clinic and also functioned as a coordinator there, one combined entry with clearly separated bullets works fine. For example, first bullets about your clinical duties, then 1–2 bullets starting with “In addition, I…” describing your leadership responsibilities. If the leadership was truly larger in scope (e.g., hospital‑wide QI project) it often deserves its own entry. The main thing is clarity—PDs must immediately see what was routine clinical work and what was leadership above that baseline.

4. My home‑country titles sound very foreign. Should I keep them in the original language?

No. Use clear English equivalents for the ERAS “Position” line, then optionally mention the original term once in the description. For example: “Position: Chief Intern (equivalent to ‘House Officer in Charge’)” or “Coordinator, Student Scientific Committee (locally titled ‘General Secretary’).” PDs will not Google your titles. Make it easy: functional English role name first, local nuance second.

5. What if my leadership did not produce clear numbers or measurable outcomes?

You do not need perfect statistics, but you do need concrete detail. You can describe scale qualitatively: “small group of 8–10 students,” “about 50 patients per month,” “weekly meetings over two semesters.” You can also focus on structural outcomes rather than numbers: “established a new peer‑teaching schedule,” “introduced a standard form for referrals,” “created a rotating on‑call list for coverage.” The red flag is vague phrasing like “helped improve” without any explanation of what changed. If you genuinely cannot describe any structural change, mentorship, or process improvement, the role may not be worth highlighting as a core leadership entry.

You now know how to turn home‑country leadership from a throwaway line into a coherent, credible signal of readiness for U.S. residency. The next step is ruthless editing: rewriting each ERAS entry, re‑shaping your personal statement, and guiding letter writers so the same leadership story emerges from multiple angles.

Once that is in place, the next phase is different: understanding how to talk about these roles under pressure in interviews—without sounding defensive about being an IMG. But that is a separate, tactical conversation for another day.