The way faculty talk about specialties is not neutral. You are being steered—quietly, consistently—toward some fields and away from others, especially the lowest paid ones.

Let me tell you how it actually works behind closed doors.

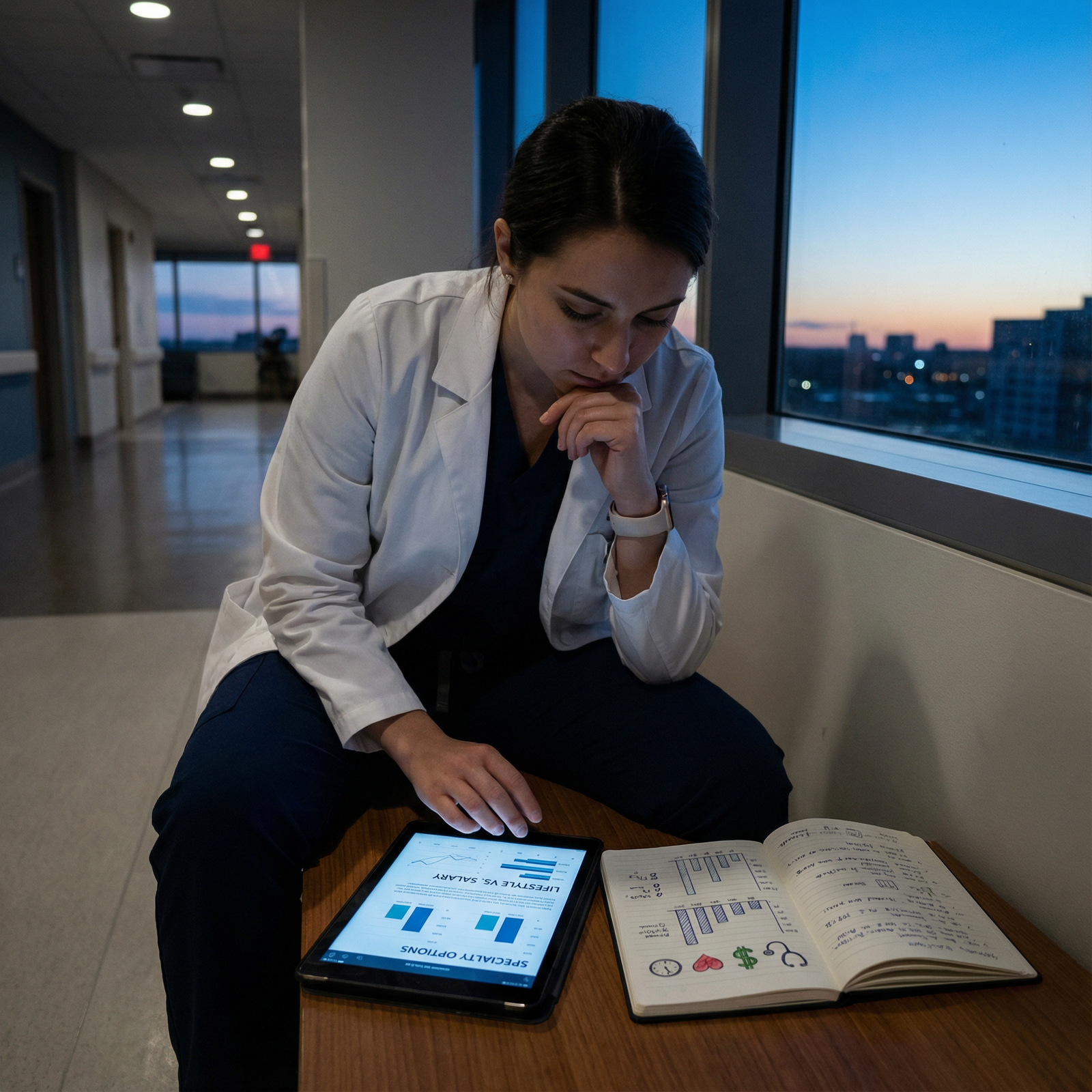

The Hidden Economics Behind “Career Guidance”

Here’s the part students almost never see: departments and faculty have economic and political incentives that shape the “advice” you get.

Every specialty has three currencies: money, prestige, and power. Low-paid fields sit at the bottom of the first category and often the second. So unless someone has a personal mission, there’s no structural incentive for faculty to actively recruit you into them.

Look at the rough medians (yes, it varies, but directionally this is real):

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Derm | 650 |

| Ortho | 640 |

| Cards | 600 |

| EM | 450 |

| IM | 320 |

| Peds | 280 |

| FM | 275 |

| Psych | 300 |

Family medicine, pediatrics, general internal medicine, psychiatry—these are the bottom tier in most compensation surveys. Yet they are also the backbone of the health system, the people actually seeing the volume of patients, managing chronic disease, catching the early signs of disaster.

Do you see schools celebrating that? Naming buildings after FM docs? Showcasing the star pediatrician at second-look day?

Not often. The spotlight goes to the transplant surgeon, interventional cardiologist, or neurosurgeon who brings in seven-figure revenue and flashy research grants.

So the culture around you starts from that bias. And culture is the first way you get steered.

The Subtle Language Faculty Use About Low-Paid Fields

Nobody walks up to you and says, “Don’t do peds, it pays badly.” They do it in softer, more plausible ways. I’ve heard these lines in dean’s offices, attending lounges, curriculum meetings.

When you say “I’m thinking about pediatrics” or “Maybe family med” or “I liked psych more than I expected,” here’s what you’ll start hearing:

“Primary care is really important, but…”

“…you’re so strong academically; you could do anything.”

“…you’ll want to make sure you can pay off your loans.”

“…you might find it repetitive after a few years.”

“…you’ll have to fight burnout with that kind of volume.”

Notice something? The compliments move you away from low-paid fields. The concerns are disproportionately assigned to them.

Flip the script. Say “I’m interested in ortho, derm, GI, interventional cards.” Watch the tone shift:

“Oh, nice, that’s a great field.”

“Very competitive—but you’re in a good position.”

“Tough lifestyle in training, but worth it in the long run.”

“A lot of doors open if you do that.”

Same faculty. Same person. Completely different framing.

This is not random. Faculty are humans with their own biases and experiences, and they transmit the unspoken value system of the institution directly into your head.

How Departments Protect Their Own—and Sacrifice Others

There’s another layer: departmental self-interest.

Every department chair knows they need a pipeline of residents and future faculty. High-paid, high-prestige fields have no trouble attracting students. Their only real “problem” is managing the flood of interest.

The low-paid fields? They’re struggling to fill residencies in the places that actually need them.

So you’d think they’d be aggressively recruiting you, right?

Sometimes they are. But here’s the ugly reality: at academic centers, even “primary care” departments aren’t always thrilled to push you toward the purest forms of low-paid practice.

The internal medicine chair at a big name place is often a subspecialist who did a fellowship in cards, GI, pulm/crit, or heme/onc. In meetings, I’ve heard exact phrases like:

“We want strong residents who keep the option open for fellowship.”

“I’d hate for our best students to cap out at general outpatient IM.”

They will not say that at a student lunch. They absolutely say it in closed faculty discussions.

What that means for you: “support” from IM or peds can often be conditional. They’re more enthusiastic if you’re “IM now, cards later” than “I want to be a continuity-care outpatient internist in a small town.”

Family medicine gets a different treatment. In many academic centers, FM doesn’t run the hospital wards. They don’t control major research dollars. Their seat at the power table is weaker. So when funding cuts or political battles happen, FM is an easy target. And that contempt filters down into how non-FM faculty talk about it with you:

“FM is fine if you want broad but not deep.”

“You’re too strong of a student to ‘waste’ on FM.”

“I see FM as a backup if your other plans don’t work.”

I’ve heard variations of those lines from surgeons, subspecialists, and even from some IM faculty.

You’re not just getting advice. You’re getting hierarchy dressed up as mentorship.

The Quiet Ways They Nudge Your Experiences

Advising is one thing. But the real steering happens in what you’re exposed to and who you meet.

Rotations: How They’re Stacked Against Low-Paid Fields

Look at how much of your third-year is really “primary care” versus specialty-driven inpatient:

– Internal medicine with complex tertiary care patients, heavy on subspecialty consults

– Surgery emphasizing high-intensity cases

– OB/GYN with a huge focus on L&D and OR

– Only a sliver of actual outpatient continuity care

Most students leave “internal medicine” thinking: this is ICU plus mega-comorbidities and 15 consults, not longitudinal panel management in a clinic. Then the same faculty look surprised when you’re not eager to be a generalist.

I’ve sat in curriculum committees where the family medicine clerkship director begged for more outpatient time and got stonewalled because “we have to protect exposure to the procedural specialties for recruitment.”

That’s steering. Just abstracted away enough that students don’t see the strings.

Letters of Recommendation: Who They Go All-In For

Faculty know exactly how to write a letter that gets attention. They also know how to subtly dampen one.

Here’s the part students underestimate: faculty triage their effort.

If you tell a big-name cardiologist or surgical oncologist you want to do derm or ortho, and you’re a “top” student, they go hard. They call program directors. They use phrases like “top 1–2% in my career.” They drop real adjectives.

Tell the same attending you’re applying to family medicine or outpatient IM, and suddenly the tone softens:

– “Hardworking and compassionate” instead of “brilliant and exceptional”

– “Will be a solid clinician” instead of “future leader in the field”

– Length and specificity mysteriously shrink

Are there exceptions? Absolutely. But I’ve seen faculty unconsciously (and sometimes consciously) “save” their strongest superlatives for students aiming at “elite” specialties.

Low-paid fields get fewer nuclear-weapon letters. Not because you’re less good, but because the writer doesn’t feel the stakes are as high.

How “Mentorship” Frames Your Choices

Mentorship meetings are where a lot of the subtle pressure shows up. The phrasing changes depending on what you say.

You: “I’m thinking about pediatrics or emergency medicine.”

Advisor: “Peds is a lovely field, but EM gives you more options down the line.”

Translation: one pays more, holds more cultural cachet, and is perceived as more “exciting.”

Or:

You: “I liked family med a lot. I could see myself doing full-spectrum.”

Advisor: pauses, then: “Have you considered IM? You could always subspecialize later.”

That “keep your options open” line is the classic move. It pulls you away from pure low-paid primary care, toward structures that funnel you back up the pay/prestige ladder.

Another pattern: they start catastrophizing your finances only when you say low-paid fields.

“I just worry with your debt level that FM or peds might make life hard.”

“I’ve seen people struggle to afford private school for their kids on those salaries.”

Funny how they don’t raise the same financial anxiety when you say “I want to do academic heme/onc and live in a high-cost city with your salary delayed by three extra years of fellowship.” That’s framed as “investment.”

The Respect Gradient You Absorb Without Realizing

Students are exquisitely sensitive to tone. You internalize who gets interrupted at grand rounds, who gets joked about, who gets the worst call rooms.

The lowest paid fields also tend to get the lowest informal status in some institutions.

I was once in a faculty meeting where someone half-jokingly said, “We don’t want to throw our best and brightest into pediatrics clinic all day,” and several people chuckled. No one called it out. That moment teaches more than any advising leaflet.

You see:

– Which specialties get the best clinic space

– Who has fellows and large teams versus who’s alone

– Which grand rounds fill the auditorium and which ones are half empty

– Who’s called “Dr. X, world expert in…” versus “our great primary care docs”

So when you’re thinking about peds, FM, outpatient psych, or general IM, you’re fighting not just numbers, but a status gradient you’ve been quietly absorbing for years.

How Program Directors Actually Read “Low-Paid Field” Applications

Now let’s flip to residency. You might think the low-paid specialties are desperate and non-selective. That’s wrong.

Program directors in FM, peds, psych, general IM are doing two things at once:

- Fighting for enough good applicants to serve their communities

- Filtering out people who don’t genuinely want the field and are treating it like a consolation prize

I’ve been on those Zoom calls. I’ve read those rank list debates.

You know who they worry about? The student who:

– Spent three years talking about ortho, then suddenly applies FM with no explanation

– Has zero primary care electives but a stack of surgical ones

– Personal statement screams, “I like procedures and the OR,” but the specialty doesn’t match

They talk about that applicant differently. “Backup vibe.” “Not sure they’re going to stay in primary care.” “Will they just try to jump ship to fellowship at the first chance?”

So while your institution may quietly devalue low-paid fields, the people actually running those residencies are often fiercely protective of them. They want residents who chose them on purpose.

This is the irony. Faculty may push you away, but once you show up with genuine commitment, primary care and low-paid fields will fight to keep you.

How to Tell You’re Being Steered (and Not Just Advised)

You’re not powerless in this. But you need to see the patterns. Here’s how you know you’re being steered, not neutrally advised:

– The concern about “your potential” only appears when you mention low-paid fields

– Faculty frame higher-paying fields as “challenging but worth it,” low-paying fields as “noble but difficult”

– You get more specific, proactive help (connections, emails, offers of advocacy) when you say competitive specialties

– Your questions about FM/peds/psych get vague answers: “It’s a good field if you’re passionate about it” and then they pivot

Pay attention to what happens when you push back a bit.

You: “I’ve thought hard about the salary tradeoff and I’m still drawn to peds—can we talk about how to match at a strong program?”

If the response is:

“Sure, let’s strategize,” → that’s a real mentor.

If the response is:

“You may change your mind; let’s not close doors,” → that’s steering.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Student interest |

| Step 2 | Faculty subtle concern |

| Step 3 | Faculty enthusiastic support |

| Step 4 | Real mentorship emerges |

| Step 5 | Steered away quietly |

| Step 6 | Connections and advocacy |

| Step 7 | Low paid field? |

| Step 8 | Student pushes back? |

What To Do If You’re Seriously Considering a Low-Paid Field

If you actually feel pulled toward one of these specialties—FM, peds, general IM, psych, sometimes even geriatrics or adolescent medicine—you’re swimming against multiple currents. But you’re not alone, and you’re not crazy.

Here’s how people who end up happy in low-paid fields usually handle this phase:

They find “true believers” inside the field. Not just someone who “teaches on the peds rotation,” but someone who:

– Chose it deliberately, despite being competitive for others

– Talks about their patients with energy, not regret

– Doesn’t immediately pivot the conversation to salary every time you mention interest

They reality-check the money—not avoid it, not obsess over it. I’ve watched students panic themselves out of FM using worst-case anecdotes from bitter attendings with three divorces and an unused boat payment.

Look at actual numbers, not myths:

| Specialty Group | Median Income (k) | Typical Call Intensity | Fellowship Needed for Higher Pay? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Med | 250-280 | Low-Moderate | Sometimes (sports, OB, addiction) |

| Pediatrics | 230-280 | Moderate | Often (NICU, cards, heme/onc) |

| General IM | 270-320 | Moderate | Often (cards, GI, pulm, heme) |

| Psychiatry | 280-320 | Low | Less often |

| Ortho Surgery | 600+ | High | Often |

Can these vary wildly by geography and practice model? Of course. But they’re not “poverty.” They’re lower relative to the outliers your school parades in front of you.

They also get very clear on what they actually like about medicine. Many of the students most tortured by this decision have never said out loud: “I like talking to people more than I like being in the OR,” or “I care more about long-term relationships than procedures.”

Once you admit that to yourself, a lot of faculty steering looks less persuasive. Because they’re trying to optimize you for a life you don’t even want.

The Real Long Game

There’s a secret faculty almost never tell you: within 5–10 years of finishing training, the variance in individual happiness has almost nothing to do with specialty income once you’re above a basic threshold.

The miserable interventionalist who never sees their kids doesn’t get happier because they cleared $800k last year. The outpatient peds doc who loves their partners, their patients, and has a stable schedule often looks like the one who “won” when they’re 45 and not burned out.

I’ve watched residents chase an extra $200k/year into specialties that made them fundamentally unhappy, then spend the next decade trying to buy their way out of that misery with vacations, houses, and early retirement schemes.

On the other side, I’ve watched FM and psych attendings quietly build lives that actually fit: fewer weekends, more control, work in communities they care about, maybe some teaching or niche clinics that light them up.

Do low-paid fields come with tradeoffs? Yes. Less raw cash. Sometimes more volume pressure. Occasionally less institutional respect at the big academic palace.

But you need to understand the game: faculty and institutional culture are optimizing you for their metrics—grant money, departmental prestige, procedural volume—not necessarily your actual life.

Your job is to notice when their steering and your values diverge.

FAQ

1. Are faculty intentionally trying to keep students out of low-paid specialties?

Usually not in some cartoon-villain way. Most of the steering is unconscious. They genuinely believe they’re “protecting” strong students from “limiting” careers. The contempt or condescension you sometimes sense toward primary care is often baked into the culture they trained in. They’ve never examined it. A few will outright say low-paid fields are “wasteful” choices; most just nudge with tone and framing.

2. How can I tell if someone is a good mentor for a low-paid specialty?

Listen for how they react when you express clear, informed interest. A good mentor becomes more concrete: talks about programs, connections, electives, ways to stand out. A bad one keeps re-opening the “Are you sure?” conversation over and over, or constantly pivots to debt and “keeping options open” even after you’ve thought it through. You want someone whose first instinct is, “Let’s help you do this well,” not, “Let me rescue you from yourself.”

3. Will choosing a low-paid specialty hurt my chances of staying in academic medicine?

Not inherently. There are academic family med, peds, psych, and general IM careers at every major institution. The bar is similar: publications, teaching, some niche expertise. What’s different is the status and resources you’re given once you’re there. Procedural fields and big-revenue subspecialties often get more toys and titles. If you care about academic promotion, you can absolutely build that in a low-paid field—you just need to be strategic about research, mentorship, and institutional politics.

4. I’m interested in a low-paid field but worried I’ll regret the income difference later. What should I actually do now?

Run the numbers brutally: loan repayment options, likely salary ranges in regions you’d live, your baseline lifestyle needs, savings potential. Then shadow actual attendings 5–10 years out in both the “high-paid” and “low-paid” paths you’re considering. Ask them, off the record, “What do you wish you’d known?” Most will tell you the truth. If after that you still feel more drawn to the work of the low-paid field, not just the idea of it, you’re unlikely to regret it. Years from now, you’ll remember whether your daily work felt like a good use of your life—not the exact number on your income line.