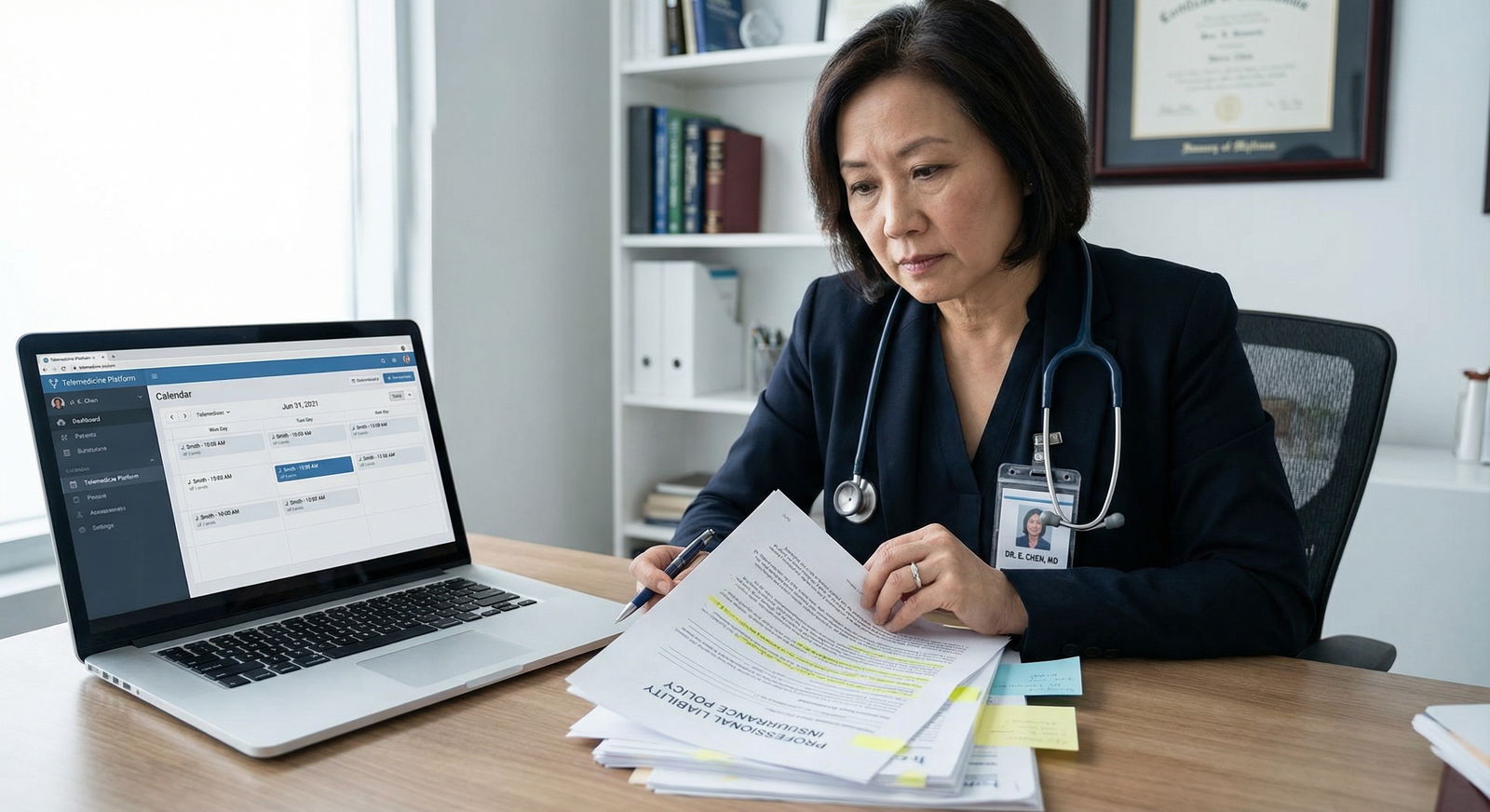

You just finished orientation as a new attending. Your inbox is a mess, your schedule is overfull, and buried in the HR portal are three different PDFs about malpractice coverage that you clicked past to get your badge activated.

Meanwhile, an older partner tells you in passing: “Remember, HR’s policy protects the hospital first. You? Maybe.” Then walks off to a meeting.

You know you “have coverage.” You do not know what that actually means when a bad outcome hits your inbasket, a patient threatens to “call a lawyer,” or a process server shows up at your clinic.

Here is the fix: you need a personal risk-management plan. Not just “malpractice insurance,” but a concrete, written system that covers:

- How you are insured

- How you practice

- How you document

- How you respond when something goes wrong

I will walk you through exactly how I would build that plan if you were my colleague, we had two hours, and a whiteboard.

1. Start With a Personal Risk Audit

Before you buy or change anything, you need to know where you are exposed.

Step 1: Map your professional roles

Write down, in plain language, every way you practice:

- Employed by hospital or large group

- Independent contractor / 1099 locums

- Side telemedicine gig

- Moonlighting in an ED/urgent care/SNF

- Informal “curbside” consults for friends / family / staff

- Volunteer clinics, medical missions

If it is clinical decision-making with your name on it, it is risk.

For each role, jot:

- Employer/entity name

- Whether they say they provide malpractice

- Whether you have anything about coverage in writing

If it is not in your contract or an official policy document, assume you are not covered until proven otherwise.

Step 2: List your risk multipliers

You already know this, but stop pretending it is not true:

- Certain specialties = higher target value

- OB/GYN, neurosurgery, EM, anesthesia, ortho, hospitalist with procedures, pediatrics

- Certain settings = messy documentation and unclear ownership

- ED handoffs, night float, cross-cover, telemedicine, SNFs

Also list:

- Procedures you perform (lines, LPs, scopes, sedation, injections)

- High-risk meds you commonly use (anticoagulants, chemo, insulin drips, opioids)

- Vulnerable populations (peds, OB, psych, incarcerated patients)

You are not doing this to scare yourself. You are building a map of where you must be airtight.

2. Understand Your Malpractice Coverage Types (Without the Buzzwords)

Most junior attendings nod through this part and then get burned five years later when they change jobs. Let’s fix that now.

| Feature | Occurrence Policy | Claims-Made Policy |

|---|---|---|

| Covered by | Date of incident | Date claim is filed |

| Need tail when you leave? | No | Yes, usually critical |

| Premium cost (typical) | Higher | Lower early, rises over time |

| Common with | Large systems, some hospitals | Private groups, many telemed/locums |

Occurrence coverage

- If the event happened while the policy was in force, you are covered.

- Even if someone sues you 7 years after you left that job.

- You do not need tail.

- Simple and usually safer for you, more expensive for whoever is paying.

Claims-made coverage

- The policy that is active when the claim is made is what matters.

- If you leave and do not have coverage for that “tail” period, you can be personally exposed.

- This is where people get destroyed after job transitions.

Your immediate action items

Pull every contract and policy doc you can find and answer:

- Is it occurrence or claims-made?

- If claims-made:

- Who owns the policy (you, group, hospital)?

- Who is contractually responsible for tail coverage when you leave?

If the answer to “who pays for tail” is vague, missing, or “to be discussed,” that is a flashing red light.

3. Build the Core of Your Personal Risk-Management Plan

Now we turn this from vague understanding into a concrete plan.

Your written plan should include:

- Coverage inventory

- Practice and documentation standards

- Communication and informed consent rules

- Incident response protocol

- Legal and financial backup

Let’s walk through each.

4. Coverage Inventory: Get It in Writing and Fill Gaps

This is non-negotiable. You need a one-page overview of all your coverage.

Step-by-step coverage check

Get certificate of insurance (COI) for each role

Ask credentialing or risk management specifically:- Limits per claim and aggregate (e.g., $1M / $3M)

- Policy type (occurrence vs claims-made)

- Named insured (you individually or just entity?)

Check side gigs separately

Telemedicine, locums, urgent care chains often provide claims-made with low limits or carve-outs. Read those policies or have a coverage-savvy broker review them.Identify uncovered activities

Typical blind spots:- Independent consulting outside the main employer

- Volunteer clinic work

- “Off the record” advice via text/email to colleagues’ family

For anything uncovered, you either:

- Stop doing it, or

- Add coverage (personal malpractice policy or rider)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Primary Job | 95 |

| Moonlighting | 60 |

| Telemedicine | 50 |

| Volunteer Clinic | 30 |

Do you need your own policy?

You are an employee in a big system, they provide occurrence coverage, and you do zero external work? You may not need your own primary policy.

You moonlight, do telemedicine, or are paid as an independent contractor anywhere? Seriously consider:

- A personal malpractice policy that:

- Names you individually

- Covers all your professional activities, not just one site

- Has at least $1M / $3M limits (or whatever is standard in your state/specialty)

This is where a good independent malpractice broker is actually useful. Not the random agent that sold you disability.

5. Practice and Documentation Standards: Your Day-to-Day Risk Shield

Most lawsuits are not about a single insane mistake. They are about patterns: sloppy documentation, poor follow-up, inconsistent communication.

Time to set your own standards.

Clinical practice rules (write these down)

No undocumented care. Ever.

If you gave advice, you chart it. Even for “just a quick question” while you are in the hallway.No prescriptions for friends and family beyond true emergencies

And if you do in an emergency:- Keep it narrow (short duration, low-risk meds)

- Document it somewhere, even if as a scanned note to self

Standardize high-risk workflows

Create your own checklists or templates for:- Anticoagulation starts / changes

- High-risk discharges (chest pain, syncope, new neurologic deficits, leaving AMA)

- Handoffs of unstable patients or unclear follow-up

Never bypass systems that exist for a reason

Examples:- Off-the-record imaging reads

- Unlogged telephone orders

- Giving verbal orders through a third party

You will feel pressure as a junior attending to “be efficient” or “not make things complicated.” That is how people create untraceable decisions that come back to haunt them.

Documentation that actually protects you

You are not writing novels. You are documenting thinking and communication.

Key habits:

For significant decisions:

- Briefly state your differential and why you did not choose certain options.

- Example: “Considered meningitis but afebrile, nuchal rigidity absent, normal mental status, and no photophobia. Will monitor and re-evaluate if headache worsens or fever develops.”

For test refusals / leaving AMA:

- Document:

- The specific risk explained

- That patient verbalized understanding

- That they were offered alternatives and follow-up

- Have them sign if your system has a form. If they refuse to sign, document that too.

- Document:

For handoffs:

- Identify high-risk issues and clear action items.

- “To oncoming: watch labs” is useless.

- “Pending CT abdomen; if negative, discharge with GI follow-up, if positive for appendicitis, call surgery” is real.

6. Communication and Informed Consent: Matching Reality to the Chart

Patients rarely sue because a form was missing.

They sue because they felt blindsided, dismissed, or lied to.

Build your own informed consent script

You can use the hospital form. But you need your own script in your head. For any invasive procedure or high-risk treatment, cover four things in plain language:

- What we are doing

- Why we are doing it (and what happens if we do not)

- Common risks and serious but less common catastrophic risks

- Reasonable alternatives

Then your documentation reflects that:

“Discussed with patient: purpose, alternatives including no treatment, common risks (bleeding, infection, pain) and serious risks (nerve injury, need for further surgery). Patient verbalized understanding and agreed to proceed.”

You do not need paragraphs. You need believable evidence that this was a real conversation.

Handling complaints early

You need a personal rule: You hear about an upset patient, you engage early.

- Do not punt everything to admin.

- Do not get defensive in the chart.

- Do:

- Listen without interrupting

- Acknowledge their experience

- Correct factual misunderstandings gently

- Loop in risk management if they mention “lawyer,” “sue,” or “report you”

Often, honest, non-defensive communication plus a prompt explanation and a plan prevents escalation. I have seen more potential claims die this way than with any form.

7. Incident Response: What You Do the Day Something Goes Bad

This is the part nobody wants to think about. Which is why most people do it badly when it happens.

You need a pre-written Incident Response Protocol. Laminate it if you want. Seriously.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Adverse Event Occurs |

| Step 2 | Stabilize Patient |

| Step 3 | Notify Appropriate Team Lead |

| Step 4 | Objective Factual Documentation |

| Step 5 | Notify Risk Management |

| Step 6 | Monitor and Follow Up |

| Step 7 | Do Not Alter Record |

| Step 8 | Cooperate With Internal Review |

| Step 9 | Potential Claim? |

Immediately after an adverse event

Stabilize and treat the patient.

This is not the time to think about liability. Do the right thing medically.Document objectively, early, and once.

- Write a factual note: timeline, decisions, patient status, who was notified.

- Avoid blame, speculation, or emotional language.

- Do not “edit” the chart later to make yourself look better. That is how you turn a bad case into a fraud case.

Notify the right people

Typically:- Your direct supervising physician / department chief

- Risk management / patient safety officer

- Your malpractice carrier if your institution policy requires it

If you are unsure whether to call risk management or your carrier, err on the side of calling. You are not admitting guilt; you are starting a protection process.

What you do not do

- Do not alter old notes.

- Do not text colleagues about “covering” or “fixing” the story.

- Do not apologize in a way that sounds like a legal admission if your jurisdiction has not adopted “apology laws” or you have not talked to risk.

You can express empathy:

“I am sorry this happened to you. We are reviewing exactly what occurred and will be transparent with you.”

That is different than: “This was my fault, I messed up.” There is a legal line. Ask risk management where that line is in your state.

8. Legal + Financial Backstop: Asset Protection and Documentation Control

Your malpractice coverage is your first barrier. It should not be your last.

Asset protection basics for junior attendings

You do not need an offshore trust in your first attending year. But you do need to stop being reckless.

Core steps:

- Max out protected accounts:

- 401(k), 403(b), 457(b), IRAs – in many states, these are heavily protected from creditors.

- Title major assets correctly:

- Discuss with a local asset protection attorney whether “tenancy by the entirety” (if married) or other forms give you extra protection in your state.

- Keep business and personal finances separate:

- If you ever form an LLC or professional corporation, treat it like a real entity, not a second checking account.

Control of your professional records

Expect at some point:

- Subpoena for records

- Request for deposition

- Inquiry from a state board

You cannot prevent that entirely. You can be prepared:

- Know who controls your medical records (employer, group, your own practice).

- Know the process for:

- Getting a copy of your own notes

- Requesting an audit trail (who accessed/edited the chart)

- Adding an addendum vs altering a note

Never alter an old note once you suspect litigation. If you realize something is wrong or missing, add a dated addendum that clearly states:

- Today’s date

- That this is an addendum

- What you are clarifying or correcting

You are better off with a transparent correction than a forensic EHR trail showing you silently rewrote history at 2:13 a.m.

9. Put It All Together: Your Personal Risk-Management Playbook

At this point, you have pieces. Now I want you to turn this into an actual, brief document you could hand to future-you in a crisis.

Your playbook should include:

- Coverage grid – each job/role, type of coverage, limits, tail responsibility.

- Practice rules – bullet list of your personal non-negotiables (no undocumented advice, no casual prescriptions, standardized consents).

- High-risk checklists – 1-page templates for:

- Discharge of high-risk patients

- AMA documentation

- Major procedures or high-risk meds

- Incident response protocol – stepwise “if X happens, I do Y, then Z.”

- Key contacts – phone and email for:

- Risk management

- Your malpractice carrier

- A medical malpractice defense attorney (yes, find a name in advance)

- Your personal insurance broker

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Coverage Inventory | 25 |

| Practice Standards | 25 |

| Incident Response | 20 |

| Asset Protection | 15 |

| Training/Review | 15 |

Maintenance schedule

Risk management is not “set and forget.” You are not buying a dishwasher.

Set calendar reminders to:

Annually:

- Review coverage (any new roles? new side gigs?)

- Confirm tail obligations if you are considering changing jobs

- Update your checklists and scripts based on real cases you saw

Whenever you change jobs or add a gig:

- Ask explicitly about malpractice type, limits, and tail responsibility.

- Get it in writing before you sign. If they shrug this off, proceed with caution.

10. Training Yourself Out of the “Junior” Mindset

Last piece. Risk management is as much about mindset as paperwork.

You are no longer a resident whose name is buried in an attending’s note. Your name is the one on the complaint.

So you need to:

- See yourself as the final common pathway.

- Stop doing things because “everyone else does it.”

- Start doing things because they are defensible, reproducible, and documented.

Practical ways to level up:

Sit in on at least one morbidity and mortality (M&M) with defense lens:

- How would you defend the decisions in this case only from the chart?

- What sentences are missing that would have changed the entire story?

Ask a trusted senior partner:

- “If you were me, what are three documentation habits that have saved you in depositions?”

- Steal those habits.

Do one short teaching session with residents/APPs on “defensible documentation.”

Teaching forces you to clean up your own.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Year 0-1 - Build coverage inventory | Done |

| Year 0-1 - Create practice standards | Done |

| Year 1-3 - Refine checklists | Ongoing |

| Year 1-3 - Handle first incidents | Ongoing |

| Year 3+ - Review and upgrade coverage | Ongoing |

| Year 3+ - Mentor others on risk | Ongoing |

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Do I really need my own malpractice policy if my hospital says I am fully covered?

Maybe not, but do not take their word for it. If you are a pure W-2 employee, only practice within that system, and they provide occurrence coverage with standard limits, you may be adequately covered for that role. However, the instant you do anything outside that umbrella—moonlighting, telemedicine, consulting—you should assume you need your own policy or explicit written coverage from that entity. Always verify policy type, limits, and tail responsibility before you rely on “you’re covered.”

2. How much should I worry about being personally bankrupted by a lawsuit as a junior attending?

Less than the horror stories suggest, but more than the ostriches think. In most cases, if there is adequate malpractice coverage and you did not commit fraud or criminal acts, plaintiffs go after the policy limits and institutional wallets. That said, if you are underinsured, have no tail, or have large unprotected personal assets, you are a much more tempting target. The goal of your risk-management plan is to make you boring and expensive to attack personally.

3. What is the single highest-yield change I can make this month to reduce my risk?

Standardize your handling and documentation of high-risk discharges and refusals. Write a simple checklist for patients leaving AMA, refusing tests, or being discharged with potentially serious conditions (chest pain, neuro complaints, possible sepsis). Use it every time. Clearly document: the specific risks discussed, the alternatives offered, the patient’s understanding, and the plan for follow-up or return. That one change alone dramatically improves your defensibility in a huge chunk of common lawsuits.

Key takeaways:

- Do not assume you are covered. Verify policy type, limits, and tail obligations for every role and side gig.

- Protect yourself daily with defensible practice habits: no undocumented care, standardized informed consent, and tight documentation of high-risk decisions.

- Have a clear incident response protocol and basic asset protection in place so that when something does go wrong—and it eventually will—you are reacting from a plan, not from panic.