The biggest threat to your mom’s care is not the disease. It’s her children fighting about what to do.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably in the middle of that fight. One sibling wants “everything done,” another thinks it’s time for hospice, someone else isn’t answering texts but shows up to veto every decision. The clinicians start avoiding the room. Nurses are confused. Your mother’s care stalls.

Let’s cut through the noise. Here’s what you actually do in this situation—step by step, from someone who’s watched these sibling wars play out at the bedside more times than I can count.

1. Get Crystal Clear on the Legal Reality (Not the Family Myth)

Most families run on “myths” about who’s in charge.

“I’m the oldest, so I decide.”

“I’m the one who lives closest.”

“I’m the only one Mom trusted.”

Legally? None of that matters if it’s not on paper.

Start here, ruthlessly:

Ask: “Is there an advance directive, living will, or healthcare power of attorney (POA)?”

- Ask the hospital/clinic social worker or case manager.

- Ask your mom’s primary care office.

- Ask your siblings if anyone has the folder/binder/safe documents.

If there is a healthcare proxy/POA:

- That person is the legal decision-maker if your mother lacks capacity.

- The proxy’s job is to represent her wishes, not their own.

- Siblings can advise, argue, cry, whatever. But the proxy is the one the medical team must follow, unless they’re clearly abusive or out of line with known wishes.

If there is no POA and she cannot decide for herself:

- State law kicks in. Most states have a priority list: spouse → adult children → parents → siblings → etc.

- When there are multiple adult children, some states say “majority rules,” others say “all must agree,” and some let the physician choose a “default” spokesperson when there’s conflict.

Here’s what this often looks like in practice:

| Rank | Typical Priority (varies by state) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Court-appointed guardian |

| 2 | Healthcare POA / proxy |

| 3 | Spouse or domestic partner |

| 4 | Adult children (collectively) |

| 5 | Parents / adult siblings |

You don’t have to become a health-law expert. But you cannot manage sibling conflict if you’re all operating on fantasy rules.

If nobody knows the rules, tell the attending physician or social worker, “We clearly disagree as siblings. Can you explain who the legal decision-maker is under our state law?” Make them say it out loud in front of everyone.

2. Separate Three Things: Wishes, Facts, and Feelings

Most sibling conflicts become a tangle because everyone is arguing about different things at the same time.

You must pull them apart:

- What Mom wants (or likely would have wanted).

- What the medical facts and options are.

- How each sibling feels about it personally.

If you do not separate these, the conversation will go in circles.

A. Start with your mother’s wishes

This is the ethical backbone. Not your hopes. Not your guilt. Hers.

Ask out loud, in a family meeting if possible:

- “What has Mom said before about being on machines, feeding tubes, or ‘not being kept alive’?”

- “When Dad was sick, what did Mom say about what she’d want for herself?”

- “Did she ever comment on someone else’s cancer, stroke, dementia, or nursing home stay?”

The patterns matter. I’ve seen families remember lines like:

- “If I can’t recognize my grandkids, that’s no life for me.”

- “I do not want to be a vegetable.”

- “Do everything you can, but if it’s just suffering, let me go.”

Write these down. Literally. On paper. That becomes your “anchor” when the emotions spike.

If she still has decision-making capacity (more on that in a second), the argument should be over: it’s her call. Your job is to support, not override.

B. Get the facts from the medical team—not from each other

Siblings love playing telephone with medical information. That’s how you get nonsense like:

- “The doctor said there’s a 50–50 chance she’ll walk again” (doctor actually said: “Small chance of some improvement.”)

- “They said the surgery will fix it” (actually: “This might stabilize things, but it won’t reverse the damage.”)

Stop debating the facts in the hallway. You’re not going to win that way.

Request a family meeting with the clinical team. Use that exact phrase.

Say something like:

“We as adult children are not in agreement about Mom’s care plan. Can we schedule a family meeting with the attending physician, bedside nurse, and social worker to review her condition and options together?”

During that meeting:

- Ask: “What’s the best realistic outcome? What’s the worst? What’s the most likely?”

- Ask: “What would this treatment mean for her day-to-day life in 1 month, 3 months, 1 year?”

- Ask: “From a medical perspective, are we prolonging life or prolonging dying?”

Then shut up and let the team talk. Don’t interrupt with “but she’s a fighter” every 20 seconds. You’ll need the full picture.

C. Acknowledge feelings as feelings—not as medical arguments

Your brother saying “I can’t just let her go” is not a clinical statement.

Your sister saying “This is not what Mom wanted” might be, but it might also be her own fear of watching a slow decline.

Label them.

“I hear that you’re scared of losing her.”

“I hear that you feel guilty because you haven’t been around as much.”

“I hear that you’re afraid of more suffering.”

Does that magically fix conflict? No. But it keeps you from smuggling emotions in as “facts.”

3. Capacity: If Mom Can Still Decide, Let Her Decide

Here’s where people get weirdly controlling.

If your mother still has decision-making capacity, the ethical and legal priority is simple: she decides. Even if you hate the decision.

Capacity is not binary. It’s task-specific and time-specific. Someone might be confused at 3 a.m. on pain meds but perfectly lucid at 10 a.m. after breakfast.

Ask the treating physician directly:

- “Do you believe she currently has decision-making capacity for this choice?”

- “If not right now, are there times of day when she’s clearer?”

- “What do you need to see or assess to determine capacity?”

If she does have capacity:

- Ask the doctor to explain options directly to her, in simple terms.

- All siblings can be present if she wants, but the questions should go to her.

- And then—hard part—you honor what she says.

If she doesn’t have capacity, that’s when the proxy or default decision-maker steps in, using substituted judgment: “What would Mom choose, if she could fully understand and speak for herself?”

Not: “What do I want?”

Not: “What will make me feel less guilty?”

“What would she choose?”

4. Confront the Classic Sibling Roles Head-On

I’ve seen the same four characters show up again and again:

- The Long-Distance Sibling: Flies in twice a year, wants aggressive care, usually in denial.

- The Primary Caregiver: Exhausted, burned out, more ready to accept hospice or comfort care.

- The Martyr: “I’ll take her home, I’ll do it all,” but has no realistic plan and burns out in 3 weeks.

- The Ghost: Avoids hospitals, avoids hard talks, but has strong opinions via text.

If you recognize yourself or others in these, say so. Out loud.

“Look, I know I live far away and haven’t been the one at the appointments. I may be reacting more emotionally.”

“I know I’m exhausted from doing this for two years. I don’t want that to push me into shortening her life.”

This kind of honesty doesn’t make the conflict vanish, but it makes it more honest. Less passive-aggressive.

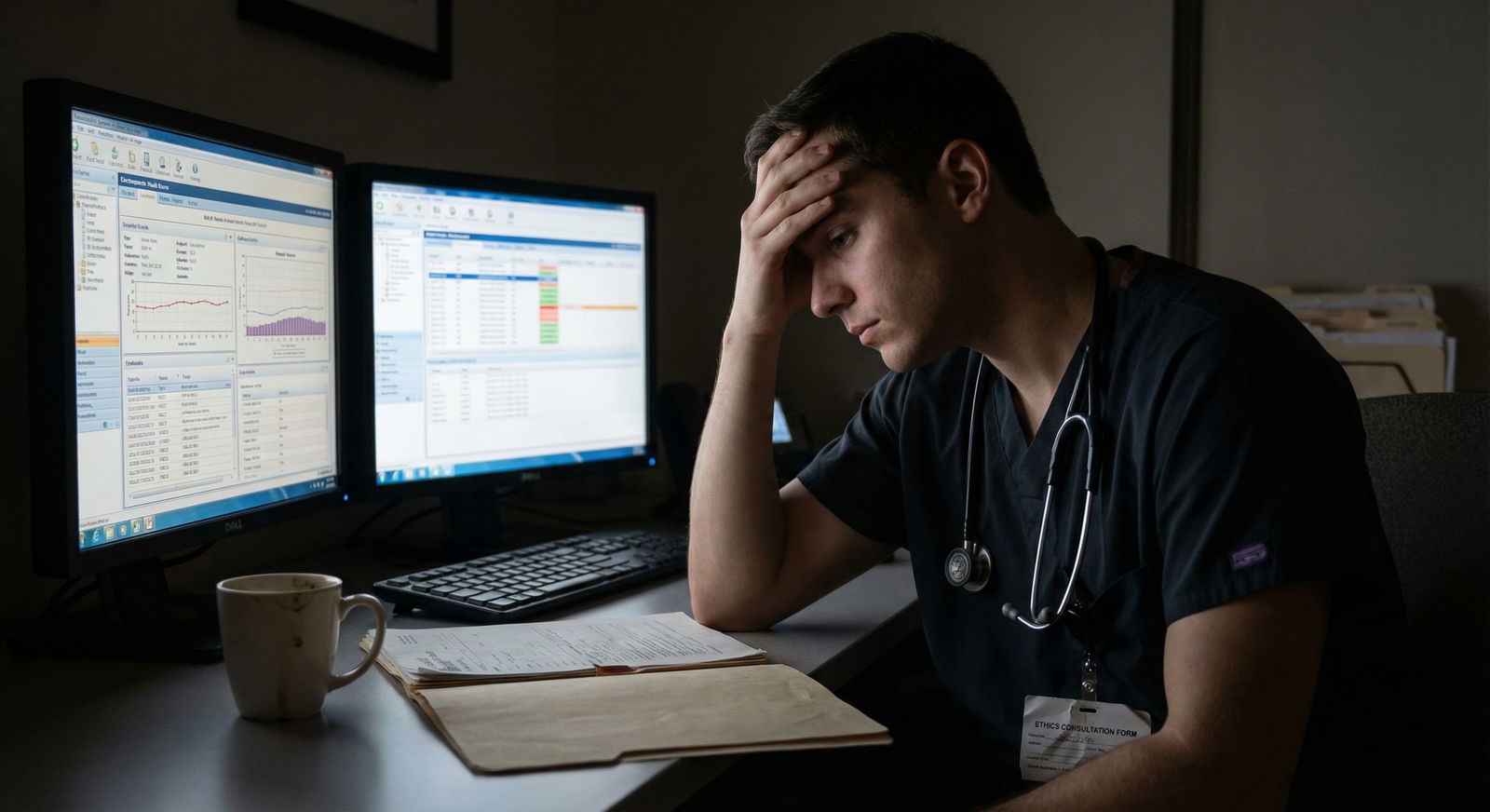

5. Use the Hospital’s Built-In Conflict Tools (That Most Families Ignore)

You are not the first family to blow up over a care plan. Hospitals plan for this. Use their tools.

A. Social worker / case manager

These people do more family therapy than discharge planning, honestly.

Ask them to:

- Facilitate a family meeting.

- Help translate medical talk into plain language.

- Reality-check things like “I’ll bring Mom home and take care of everything on my own.”

B. Ethics consultation

This sounds dramatic, but you’re not “calling the cops.” Ethics consults exist for exactly your situation.

Tell the doctor or nurse:

“We’re really stuck as a family on what’s right for Mom. Could we request an ethics consult?”

What they do:

- Clarify the medical realities.

- Clarify who the legal decision-maker is.

- Align choices with your mom’s values and prior statements.

- Sometimes, bluntly tell one sibling, “That option is not medically appropriate anymore.”

I’ve sat in ethics meetings where the oncologist said, “More chemo will not extend life. It will only cause more suffering.” Hearing that from a neutral committee, not just one doctor, helped the aggressive sibling finally back down.

C. Palliative care team

Palliative care is not “giving up.” It’s specialized support focused on:

- Symptom control (pain, breathlessness, agitation).

- Clarifying goals of care.

- Helping families work through conflict and grief.

If anyone says, “We’re not ready for hospice,” you can still ask:

“Can palliative care see her while she’s still in the hospital?”

They’re often far better than surgeons or intensivists at family conversations.

6. Move From Positions to Principles

Right now the argument probably sounds like this:

- “We have to do everything!”

- “You’re being selfish, she’s suffering!”

- “Hospice is just killing her!”

- “You just don’t want to deal with her anymore!”

Those are positions. Dig under them to the principles everyone actually cares about. Usually some version of:

- Not wanting her to suffer.

- Not wanting to abandon her.

- Wanting to respect her wishes.

- Wanting to feel at peace with your own choices.

In a calmer moment, say:

“Let’s list what we all agree we want for Mom, even if we disagree on how to get there.”

You’ll usually get something like:

- We don’t want her in pain.

- We want her treated with respect.

- We don’t want pointless procedures.

- We want her to feel loved and not alone.

Then you can ask: “Given these shared goals, which option best fits them—continued ICU care, rehab, or hospice?”

You’re not looking for 100% emotional comfort. You’re looking for the least-bad option aligned with her values.

7. Decide How to Disagree Without Blocking Care

Sometimes, there will be no perfect consensus. You still have to move.

If you’re the legal decision-maker:

You listen, you consult the records (advance directive, prior statements), you hear the doctors, and then you decide. You can say:

“I’ve heard everyone’s opinions. This is heartbreaking for me too. Mom trusted me with this decision, and based on what she has said in the past and what the doctors are telling us, I believe she would choose comfort-focused care now.”

If you’re not the decision-maker:

You can say your piece clearly, then step back.

“I want it on record that I’m worried we are stopping too early. But I also know [sibling] is the proxy. I’ll support being there for Mom, even though I see it differently.”

What you don’t do:

- Verbally attack staff.

- Sabotage the plan (“I told the nurse to ignore the DNR.”)

- Threaten lawsuits every 10 minutes.

- Block hospice or rehab referrals just to delay.

If you truly believe your proxy sibling is acting against your mother’s known wishes in a serious way (e.g., demanding aggressive treatment your mother explicitly rejected in writing), you can:

- Ask for an ethics consult.

- Ask risk management or social work how to raise a concern formally.

- In extreme cases, seek emergency court involvement. But that’s nuclear-level, and by the time it moves, your mother’s condition may have changed anyway.

8. Protect Relationships You’ll Need After the Funeral

Here’s the ugly truth: how you handle this will echo for decades. I’ve seen siblings stop speaking for 20 years over one ICU decision.

So while you’re fighting about ventilators and feeding tubes, remember:

There is a point at which you’re no longer arguing about her care. You’re litigating childhood wounds.

Set some ground rules:

- No personal attacks (“You were never around” can be true, but it’s not useful now).

- No weaponizing your caregiving (“I wiped her, so I decide everything”).

- No “You’re killing her” or “You just want her dead.” That language is poison.

One practical strategy I’ve seen help:

Assign roles instead of “winners.”

- One sibling: primary medical spokesperson / proxy.

- One sibling: logistics (insurance, bills, forms).

- One sibling: emotional support (sitting with Mom, coordinating visitors).

This gives each person legitimate importance without needing to control the entire plan.

9. Preparing Yourself Ethically: What You Have to Live With

You are not going to leave this situation feeling great. Best case, you feel “less terrible.”

Here’s the ethical target:

- You prioritized your mother’s values over your own fear and guilt.

- You sought clear medical information instead of hiding in denial.

- You used the tools available (family meetings, ethics consult, palliative care).

- You treated your siblings like flawed human beings, not enemies.

- You did not let perfectionism paralyze time-sensitive decisions.

When you’re sitting years later wondering “Did we do the right thing?”, the answer won’t come from whether she lived 3 more weeks or died 2 days earlier. It’ll come from whether you can honestly say:

“We did our imperfect best to honor what she would’ve wanted, with the information we had.”

That’s as good as it gets in real life.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Different beliefs about suffering vs longevity | 30 |

| Unequal caregiving load | 25 |

| Guilt/old family dynamics | 20 |

| Misunderstanding of prognosis | 15 |

| Legal authority disputes | 10 |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Sibling Disagreement Starts |

| Step 2 | Check Legal Decision Maker |

| Step 3 | Clarify Mom Wishes |

| Step 4 | Family Meeting With Medical Team |

| Step 5 | Implement Care Plan |

| Step 6 | Request Ethics Consult |

| Step 7 | Adjust Plan Based on Values and Facts |

| Step 8 | Decide How to Disagree Without Blocking Care |

| Step 9 | Still Major Disagreement |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Full Code ICU Care | 80 |

| Selective Treatments | 65 |

| Comfort Focused in Hospital | 50 |

| Home with Hospice | 40 |

FAQs

1. What if one sibling keeps insisting on “everything” even when doctors say it’s futile?

You do not negotiate medical reality. If the team is saying further aggressive treatment will not change the outcome and only cause suffering, that sibling’s demand isn’t an “option,” it’s a wish.

Ask for a joint meeting where the doctor plainly states what’s medically appropriate and what’s not. Ask specifically:

“Is this treatment medically indicated, or would you consider it non-beneficial/futile?”

If it’s non-beneficial, the team is not ethically required to provide it, even if a family member insists. This is where an ethics consult is useful—they can back up the clinicians and explain that “doing everything” sometimes means maximizing comfort and dignity, not interventions.

2. Can the hospital force a decision if we can’t agree?

They’re not going to drag your mother to surgery against a divided family’s wishes. But they also won’t allow her to sit in limbo forever.

What often happens:

- The treating team clarifies who the legal decision-maker is.

- They make a recommendation aligned with standard of care and her presumed wishes.

- If there’s persistent conflict, they may use the ethics committee to confirm the plan is ethically justifiable.

- After that, they proceed with the recommended plan, even if some siblings remain upset, as long as the legal decision-maker agrees.

If literally no one can or will decide, the hospital might go to court to get a guardian appointed. That’s slow, public, and usually worse for everyone.

3. What if Mom never talked about her wishes and has no paperwork?

Then you’re using best-interest standard instead of substituted judgment. You look at:

- Her current condition and prognosis.

- The burdens vs benefits of each treatment.

- Her known personality and values in general (independent vs risk-averse, religious beliefs, attitude toward suffering).

Gather stories: How did she respond to other family illnesses? What did she say about “living on machines”? Even casual comments can help shape a picture.

Then, as a group—or as the legal decision-maker—you choose the path that a reasonable person in her situation, with her values, would likely choose. Not perfect, not clear-cut, but that’s the work.

Key points to carry out of the hospital and into your decisions:

- Find out who legally decides, then focus on what your mother would want—not what makes you feel safest.

- Use structured tools—family meetings, palliative care, ethics consults—to stop arguing in the hallway and start making grounded decisions.

- Aim for the least-bad, most-aligned option and protect your relationships; you’ll be living with each other long after this crisis is over.