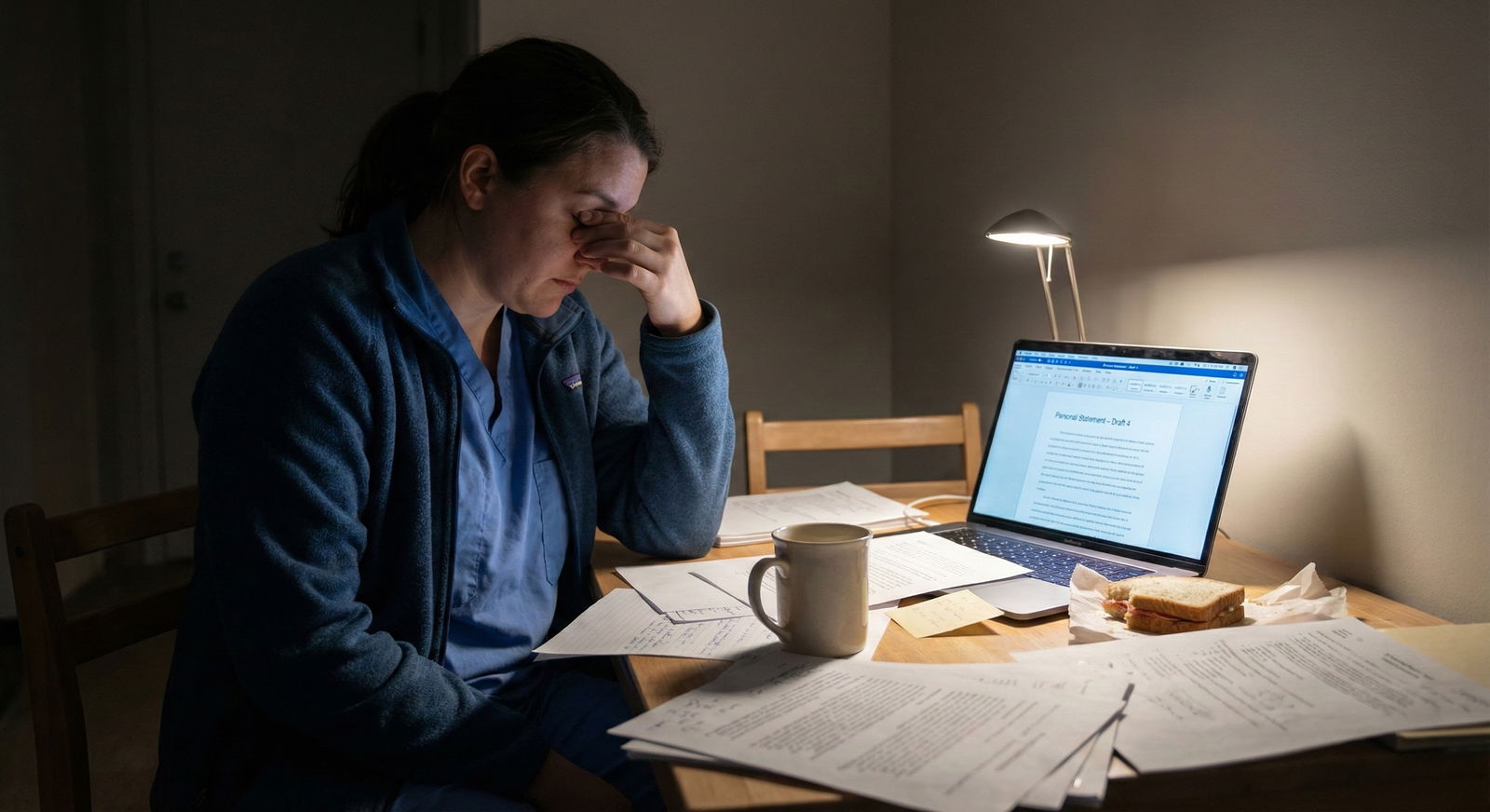

What if every program director who reads your personal statement can tell you’re a late specialty switch and immediately downgrades you for it?

Let’s Just Say It: You’re Scared They’ll Think You’re Flaky

You’re not actually asking, “Will my personal statement give me away?”

You’re asking:

- Will they think I’m indecisive?

- Will they suspect I’m using their specialty as a backup?

- Will they wonder if I’ll switch again once things get hard?

- Will they talk about me in the committee meeting like: “Didn’t this person want derm last year?”

I’ve seen people melt down over this. The panic usually kicks in somewhere between:

“I think I like anesthesia more than IM” and “Oh God, my entire CV screams neurosurgery.”

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: yes, your personal statement will reveal that you switched late… if you write it badly.

But that’s not the same as “switching late is a death sentence.”

Program directors don’t hate late switchers.

They hate late switchers who:

- Lie

- Hand-wave

- Or sound like they panicked and picked a specialty off a BuzzFeed quiz

So the question isn’t “Will they know?”

The question is: What will they conclude when they know?

That part is fixable.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Being judged as flaky | 80 |

| Seen as a backup applicant | 75 |

| Lack of commitment | 70 |

| Red flags in PS | 60 |

| Letters not aligned | 55 |

Will Programs Hold a Late Switch Against Me?

Short answer: some might. Many won’t.

And you don’t actually need all of them. You need enough.

Here’s how programs usually think about this, whether they say it out loud or not.

They care about three questions:

Do you actually understand this specialty, or are you guessing from vibes?

They’ve seen the “Grey’s Anatomy made me love surgery” people. They’re tired.Did you run toward this specialty for specific reasons, or just away from another one?

This is where a lot of late switchers screw themselves. They write one big “I hated surgery” essay instead of “Here’s why I chose psych.”Is there evidence, anywhere, that your decision is grounded in real exposure?

Rotations, mentors, procedures, patient stories, research, QI projects, even clinic patterns. Something.

You’re convinced they’ll see your timeline and instantly toss your app.

They won’t. They skim hundreds of applications. They’re not CSI.

What actually happens:

- If your experiences + letters + personal statement all make internal sense for the specialty you’re applying to, 90% of them will not sit there trying to backward-engineer when you “really decided.”

- If your file feels like a puzzle with missing pieces, then they start wondering. And doubting.

So no, the fact that you decided on EM in May instead of December is not the fatal blow.

The fatal blow is making your personal statement highlight your confusion instead of your clarity.

The Biggest Ways Your Personal Statement “Gives You Away”

Let’s call out the landmines, because you’re probably stepping on at least one of these right now.

1. The Overcompensation Essay

This is the one where you sound like a cult member.

Every sentence: “I LOVE FAMILY MEDICINE. I’ve ALWAYS been drawn to FAMILY MEDICINE. FAMILY MEDICINE is my PASSION.”

That’s how you write when you’re terrified they’ll sense your prior interest in ortho.

Ironically, it makes you sound fake and actually more suspicious.

Normal human passion doesn’t read like screaming.

2. The Vanishing Old Specialty

You scrub every trace of your past interest from your personal statement.

You spent two preclinical years in the neurosurgery interest group, did research, did a sub-I… and in your essay, none of that exists. Not even a hint of uncertainty.

Program directors aren’t dumb. If your CV is full of OB/GYN and your personal statement pretends it never happened, it looks like you either:

- Don’t know how to integrate your own story, or

- You’re hiding something

Neither is good.

3. The “I Just Realized” Conversion Story

“I always loved medicine, but it wasn’t until my sub-I in October that I realized internal medicine was my true calling.”

In October. Of your fourth year. Right.

Do late realizations happen? Yes.

Do they sound believable when your tone is “I was blind but now I see”? Not really.

You need to show seeds of fit that existed before the “aha” moment, even if they weren’t fully conscious.

4. The Breakup Letter

This is the “I didn’t feel seen in surgery and the culture was toxic and I craved more continuity and I realized I belonged in psych” essay.

You think you’re explaining your journey.

They read it as: “This person writes long emotional letters when unhappy.”

Never attack your old specialty. Never center your story on what you didn’t like.

Talk less like a breakup. More like a clear-headed transition.

How To Talk About a Late Switch Without Screaming “RED FLAG”

Let me walk through what actually works when you’re late to the party.

1. Make Your Story Chronological, But Not Confessional

You don’t owe them your emotional diary. You owe them coherence.

A good structure if you switched:

- A brief snapshot of who you are clinically (now, today)

- A short timeline of how your interests developed

- The pivot: what you saw/experienced that made things click

- Evidence that you’ve actually acted on this decision

- What you’re looking for in residency that matches their specialty

You can talk about another specialty without apologizing for it.

For example (totally made up, but you’ll get the idea):

“I started medical school convinced I would go into general surgery. I loved the decisiveness of the OR and the clear before-and-after impact of procedures. On my core medicine rotation, I expected to miss the OR. Instead, I found myself drawn to the ongoing diagnostic puzzles, the challenge of managing complex chronic disease, and the deep satisfaction of knowing patients over time.

By the end of my third year, after a surgical sub-I and an inpatient medicine month, I realized that the parts of surgery I enjoyed most were actually the intern-level medicine problems: stabilizing sick patients, working through long differential diagnoses, and coordinating care. That’s when I deliberately shifted my focus to internal medicine.”

See what that does?

- It doesn’t pretend the original plan never happened.

- It doesn’t trash surgery.

- It names what shifted and ties it directly to things IM programs care about.

2. Show That the Decision Was Active, Not Passive

Programs are allergic to, “I kind of drifted into this specialty.”

You want to sound like you chose this, with your eyes open.

Think: verbs.

“I started… I met… I asked… I arranged… I joined… I completed…”

So instead of:

“Later in the year, I realized pediatrics fit me better and decided to apply.”

Try:

“Once I recognized how much I valued working with families longitudinally, I arranged an additional inpatient pediatrics elective, sought out a continuity clinic experience, and met regularly with my faculty mentor to make sure I understood both the demands and rewards of a career in pediatrics.”

Same late switch.

Very different level of intention.

3. Bring Receipts: Examples That Match the New Specialty

If your entire personal statement is just “I discovered I love psych,” with no concrete scenes, it reads like marketing copy.

Pick 1–2 specific clinical moments that:

- Involve the specialty you’re applying into

- Show you doing the kind of work that residency will actually involve

- Demonstrate traits they want (teamwork, communication, follow-through, curiosity, resilience)

You don’t have to manufacture a lifelong calling. You just have to show that when you were doing the work of that specialty, you came alive in observable ways.

4. Admit Timing Without Over-Apologizing

You can acknowledge you decided late. You just don’t make it your entire identity.

Something like:

“While my decision to pursue anesthesiology came later in my clinical years than for some of my peers, it followed repeated, deliberate exposure to the field…”

That’s enough. You don’t need to then write three paragraphs of self-flagellation for not deciding in M2.

The key is: late but deliberate beats early but random any day.

| Approach Type | Example Summary |

|---|---|

| Good | Acknowledges starting in another field, names specific aspects of new specialty that fit, shows extra steps taken to confirm decision |

| Problematic | Overly dramatic “conversion,” trashes old field, vague reasons, no concrete follow‑through |

| Good | Mentions late timing once, then focuses on what you’ve done since deciding |

| Problematic | Repeatedly apologizes for being late, centers entire essay on guilt and anxiety |

| Good | Uses 1–2 specific patient/clinical stories in new specialty |

| Problematic | Only stories from old specialty, or none at all |

But What If My Whole CV Is the “Wrong” Specialty?

This is the part that really keeps you up at 2 a.m., isn’t it?

You look at your ERAS and think: “Everything says ortho; my heart says radiology.”

Here’s the harsh reality and the good news.

Harsh reality: Yes, some programs will see that mismatch and think you’re hedging.

Good news: Many will just ask themselves, “Did this person make a thoughtful choice and do they now have enough alignment to succeed here?”

Your personal statement’s job becomes:

- Translating old experiences into traits that fit the new field

- Showing that your interest matured, not flipped randomly

For instance, ortho → radiology:

You might highlight:

- How much you liked imaging during pre-op planning

- The satisfaction you got from clarifying diagnoses with imaging, not just “fixing” surgically

- Your appreciation for pattern recognition, detail work, and cross-specialty collaboration

You don’t write: “I realized I don’t like the OR.”

You write: “I realized the part of the process that most energized me was understanding pathology on imaging and explaining it to the team.”

Same truth. Better framing.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Past Interests |

| Step 2 | Trigger Experiences |

| Step 3 | Reflection and Comparison |

| Step 4 | Deliberate Actions in New Specialty |

| Step 5 | Clear Decision |

| Step 6 | Evidence of Fit in PS |

Red Flag vs. Human Story: Where the Line Actually Is

You’re terrified that any sign of uncertainty = death.

That’s not how actual humans read applications.

Red flag is:

- No clear reason for the switch

- No evidence you tested the new field

- Blaming, dramatic language about your old field

- A tone that feels like you’re trying to “sell” rather than explain

Human story is:

- Interests evolved as you saw real patients

- You articulate the differences between your old and new choices

- You moved quickly to get real exposure to the new direction

- You can explain your choice in 2–3 grounded sentences

If you’re honest, your personal statement is not going to “give you away” in a bad sense.

It’s going to explain you.

And programs would rather understand you than try to guess what you’re hiding.

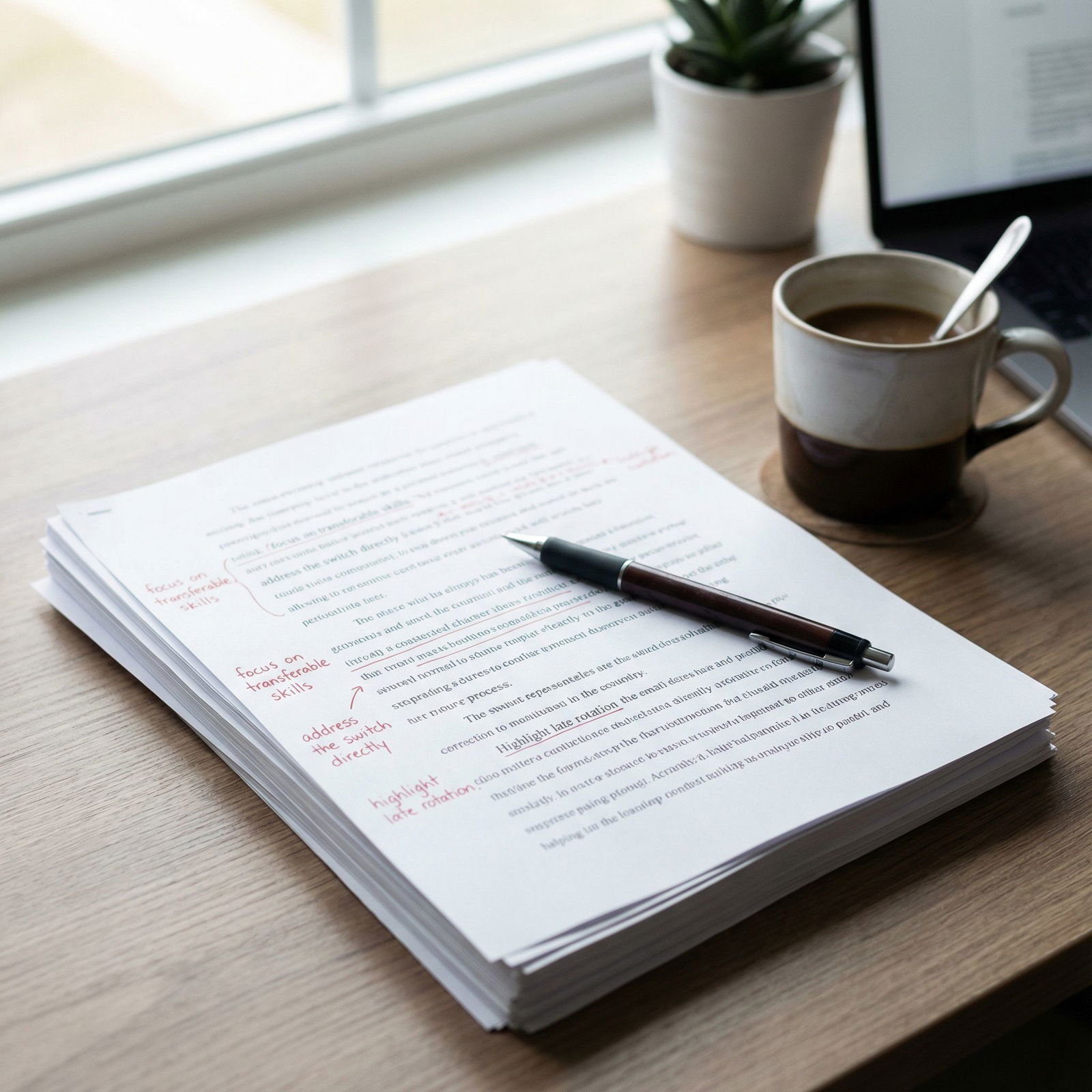

Concrete Rewrite Moves If You Switched Late

If you want something actionable, here’s what I’d literally do tonight with your draft:

Find every sentence that is just you reassuring yourself.

“I am truly passionate about…” “I am confident that…”

Cut at least half. Replace with specific actions or examples.Add one clear, honest line about the switch.

Something like:

“Although I initially planned a career in X, my clinical experiences in Y steadily shifted my focus as I recognized how much more aligned it was with how I like to think and work.”Name 2–3 concrete features of the new specialty that match who you are.

Not generic “I like teamwork.” Everyone likes teamwork in essays.Think more like:

- “longitudinal relationships with medically complex patients”

- “rapid, procedure-based problem-solving”

- “high-acuity resuscitation and systems-based thinking”

- “pattern recognition and careful image interpretation”

Add one paragraph on what you did after deciding.

Extra elective. Clinic. Research. A mentor you sought out. Something.Delete the apology paragraphs.

You don’t need to beg for forgiveness for not knowing your life’s calling at 22.

You’re not on trial. You’re just explaining how you got here.

FAQ: Late Specialty Switch & Personal Statement

1. Do I have to mention I switched specialties in my personal statement?

If your CV obviously shows deep involvement in another field (multiple research projects, leadership in that interest group, a sub-I, etc.), yes, you should briefly acknowledge it. Skipping it makes you look either evasive or clueless. One or two sentences are enough. You’re not writing a confession; you’re providing context.

2. What if I decided really, really late—like after my away rotation?

Then you’re in the “I need to show hyper-deliberateness” category. You focus heavily on: the experiences that clarified things, what you did the moment you realized (emails, meetings, extra rotations, new mentors), and how your underlying traits were always a better match for this field, even if you labeled it wrongly at first. Programs care less about the calendar date and more about whether your choice now looks stable and thought-through.

3. My letters are mostly from my old specialty. Am I doomed?

No, but you need to compensate. In your personal statement, make sure you’re crystal clear on why the new specialty fits, and try—if at all possible—to get at least one letter from someone in the new field, even if it’s from a shorter elective. Also, highlight generalizable traits your old letters will probably mention: work ethic, communication, thoroughness, teachability. You can explicitly connect those traits to what your new field values.

4. How obvious is it to programs that I switched late?

If they read carefully, they’ll probably figure it out. The question is what story they attach to that fact. “Confused and flaky” or “normal human who refined their interest with real experience.” Your personal statement heavily influences which story they choose. Don’t obsess over hiding the switch; obsess over making the reasoning sound grown-up and grounded.

5. What if I’m still low-key unsure between two specialties while writing?

Pick one for the purposes of your application. Really. Programs can smell the “I’m keeping my options open” personal statement, and they hate it. Even if you’re 80% sure, write like you’re 100% committed. Ground it in real experiences and concrete reasons. You can change your mind about fellowships later; for now, you need to present a clear, coherent version of yourself.

Years from now, you won’t remember the exact sentence where you admitted you switched late. You’ll remember that at some point, you stopped trying to hide who you were and started explaining it clearly—and that was enough.