What if your personal statement screams “I love primary care” and one of your letters basically sells you as the next great surgical oncologist? Are programs going to think you’re fake… or worse, confused and not worth ranking?

Let’s walk straight into that nightmare, because pretending it doesn’t happen doesn’t help.

First: Does Mismatch Actually Matter?

Yes. But not always in the catastrophic way your brain is telling you.

Programs absolutely look for coherence. They’re trying to answer a very specific question:

“If we invest 3–7 years training this person, do we actually know who we’re getting?”

When your story doesn’t line up across documents, a few thoughts pop into people’s heads:

- “Is this person just telling us what they think we want to hear?”

- “Are they actually undecided about specialty or direction?”

- “Who is the ‘real’ version of this applicant?”

But here’s the part your anxiety keeps skipping:

Faculty are used to imperfect, messy stories. They’ve seen people pivot from surgery to psych, from cards to palliative, from research-heavy to community-focused. Humans change. Interests shift.

What raises red flags isn’t “this person has multiple interests.”

It’s “this person feels manufactured, unfocused, or inconsistent in a way that doesn’t make sense.”

Big difference.

Types of Mismatches (And How Bad They Really Are)

Let’s break down the common conflict scenarios. Some are survivable. Some are… less ideal.

1. Specialty vs Specialty

You’re applying to Internal Medicine.

Your personal statement: “I’ve always been drawn to longitudinal relationships, chronic disease management, and complex medical decision-making.”

Your surgery letter: “They told me in the OR they plan to pursue a surgical career. They have the hands, the mindset, and the dedication to be a surgeon.”

This is the one everyone panics about.

How bad is it? Context-dependent.

- If it’s one letter from a rotation you did earlier, not this application cycle? People shrug. Students change their minds.

- If it’s a recent sub-I letter in a different specialty strongly declaring your “unwavering commitment” to that specialty? That’s trickier.

- If you applied to both specialties in the same ERAS season and your letters mention that? People absolutely notice. They talk.

2. Academic vs Community Focus

Personal statement: “I’m deeply committed to an academic career focused on research, teaching, and advancing the field.”

Letter: “They expressed a strong desire to practice in a busy community setting, where research would not be a priority.”

Programs read that and think: which is it?

Is this fatal? No. But it can make you look like you tailored your statement to “fit” academic programs while your attending actually heard something else from you in person.

3. Personality / Work Style Mismatch

Personal statement: “I work best in teams, value collaboration, and enjoy hearing diverse perspectives.”

Letter: “They prefer to work independently and often separated themselves from the team.”

Or:

PS: “I am calm under pressure.”

Letter: “They became easily flustered during busy shifts.”

This is worse than the “I changed specialties” scenario. Because now we’re not just talking direction; we’re talking character and reliability. Program directors trust letters more than your own self-description.

4. “I’m Humble and Struggling” vs “They’re a Superstar”

Oddly, this one is usually fine.

Your PS: honest about struggles, growth, self-doubt.

Letters: “Top 5% student I’ve worked with in 10 years.”

That doesn’t hurt you. It just makes you look self-aware and maybe a little modest. No one is rejecting you because your letter writers think you’re more impressive than you admit.

How Programs Actually Read These Conflicts

Let me be blunt: your worst-case scenario brain imagines a dark room, a giant projector, your application open, and a committee circling every inconsistency with red pen.

Reality is much less dramatic and much more… rushed.

Most residency application reviews are:

- 5–10 minutes per file (sometimes less)

- Skim of your PS

- Quick scan or selective reading of letters

- Heavy weight on MSPE/Dean’s Letter, Step scores, clerkship grades, red flags

The mismatch only really hurts you when:

- It’s glaring.

- It directly contradicts your stated goal for that specialty.

- It supports a narrative they already half-suspect: that you’re unfocused, not fully committed, or misrepresenting yourself.

The key thing:

No one is hunting for reasons to destroy you.

They’re skimming for a coherent, believable human they can picture in their program.

If your materials net out to: “Smart, decent, wants this specialty, will show up and work” — they’re not digging for forensic-level contradictions.

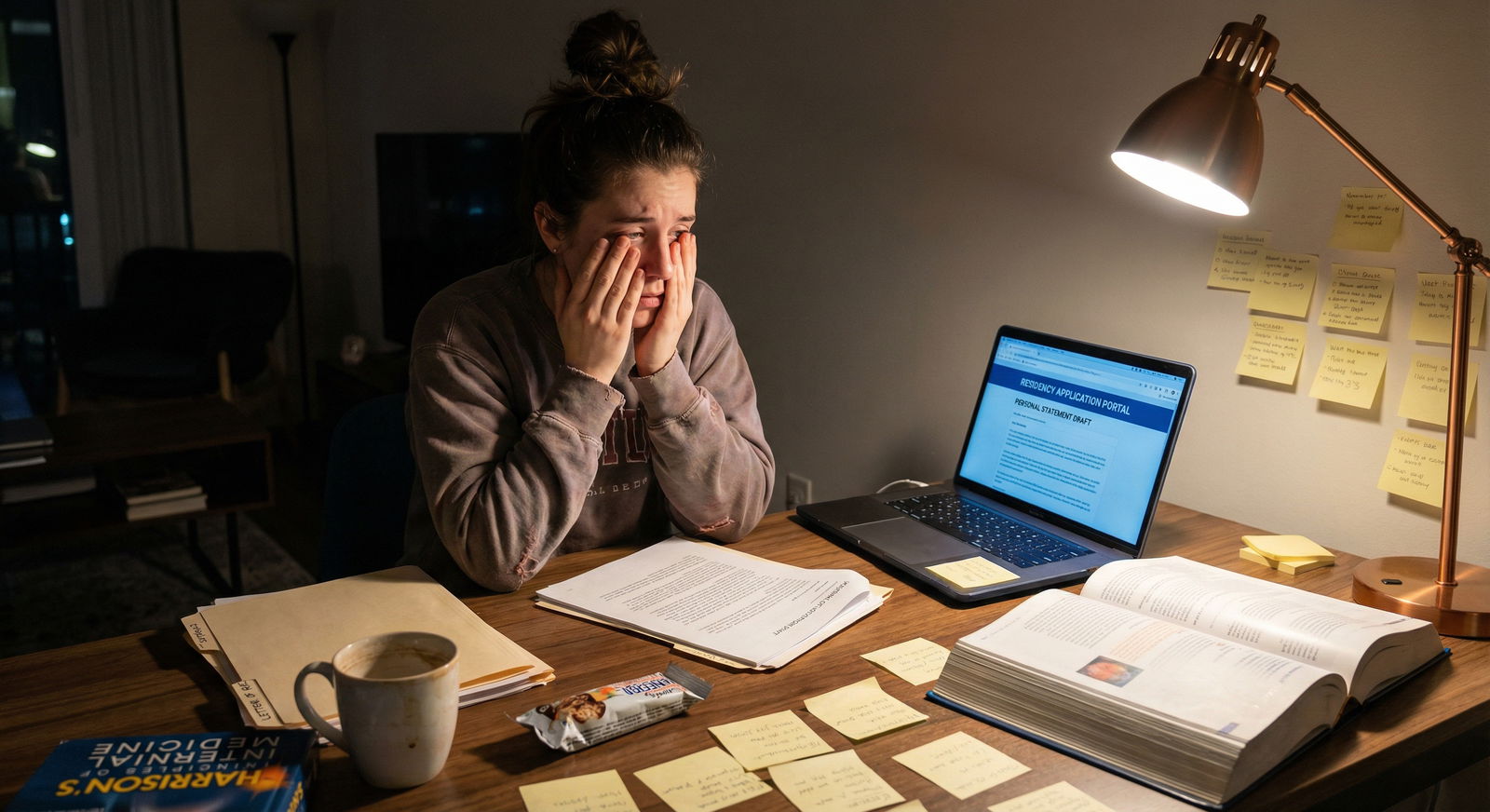

What If the Damage Is Already Done?

You submitted ERAS. You can’t pull it back. Someone tipped you off that one of your letters goes in a totally different direction than your personal statement. Or you suddenly realize your research mentor’s letter sounds like you’re married to a research career you barely want anymore.

So… now what?

Step 1: Stop spinning worst-case fantasies for 24 hours

You’re probably cycling through:

- “I won’t get a single interview.”

- “Every PD will think I’m a liar.”

- “I’ve ruined my entire career over a badly timed letter.”

I’m going to be harsh: that’s your anxiety lying to you.

You might lose some marginal benefit. You might look a bit less polished. You have not “ruined everything.”

Step 2: Identify the type of conflict

Ask yourself:

- Is this a direction mismatch? (specialty / academic vs community / research vs clinical)

- Or a character / behavior mismatch? (work ethic, reliability, professionalism)

Direction mismatches are usually survivable, especially early pivot-type ones.

Character/behavior conflicts are more serious — but those tend to show up as bad letters, not just inconsistent ones.

Step 3: Take inventory of the rest of your application

You’re not just a PS and one LOR. Programs see:

- Overall pattern of your letters: are 3 saying the same thing and 1 slightly off?

- MSPE and clinical narratives

- Grades & Step scores

- Activities: Do they match what you “claim” to care about?

If 80% of your app tells one clear, believable story, and 20% is fuzzy or inconsistent, you’re going to be okay at a lot of places.

Can You Ever Fix It Mid-Cycle?

Sometimes, a little.

Option 1: Clarify during interviews

If you get interviews, you can absolutely address mild inconsistencies when they ask:

“So what kind of career do you see for yourself?”

You can say something like:

“I’ve had a genuine evolution in my interests. Early on, I thought I wanted X — and some faculty probably still saw me that way. But over the last year, through [clerkship/experience], I realized I’m much more drawn to Y. That’s what I’m pursuing now, and it’s reflected in how I’ve spent my time this past year.”

This does a few things:

- Admits the shift instead of hiding it

- Makes it sound like growth, not flakiness

- Gives them a “story” to put all the pieces in context

Option 2: Supplemental emails (rarely ideal)

If there’s a genuinely serious conflict (like a letter that mentions a totally different specialty), you could:

- Ask your dean’s office or advisor if reaching out to specific programs makes sense.

- Very briefly explain that your interests evolved after that rotation and you remain committed to [current specialty].

Do this only if:

- The conflict is major and obvious

- You’re applying in a highly competitive specialty where every signal matters

- A trusted advisor says it’s worth the risk

Most of the time, over-explaining just draws attention to something they might not have even noticed.

Option 3: Adjust for prelim vs categorical

Some applicants apply to a categorical specialty and also to prelim medicine or surgery. That alone creates confusion.

| Application Type | Mismatch Risk | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| IM categorical only | Low | Cleanest story |

| IM + prelim medicine | Low-Medium | Usually understandable |

| Derm + prelim medicine | Medium | Needs a clear “why” story |

| Surgery + IM categorical | High | Looks unfocused or uncertain |

| EM + Anesthesia categorical | High | Programs will notice |

If your letters and PS seem to lean in different directions, you might adjust which programs you send which signals to in the future (not helpful this cycle, but very relevant if you reapply or do a fellowship).

How To Prevent This In Future Cycles (Or For Fellowships)

If you’re not fully locked in yet — or you’re quietly thinking “if I don’t match, I’m redoing everything” — here’s how to not end up here again.

1. Stop letting letter writers “guess” your goals

Before they write anything, tell them, out loud or by email:

- What specialty you’re applying to

- What type of career you actually want (academic vs community, research vs clinical-heavy)

- What qualities you hope they’ll address

Something as simple as:

“I’m applying to categorical IM with the goal of working in an academic setting with some research and teaching. I’d really appreciate if you could speak to my clinical reasoning and teamwork.”

That alone avoids 50% of the mismatch chaos.

2. Share your actual draft personal statement

Don’t be shy about sending it. Yes, it’s vulnerable. Yes, it’s awkward. Send it anyway.

Ideally:

- You send them your PS draft

- You send them your CV

- You say: “If anything in here doesn’t sound like the person you worked with, please tell me.”

If a mentor reads your statement about “lifelong love of primary care” and says, “Really? You told me you wanted ICU and cards,” that’s a sign to either update your statement or accept that you’ve changed directions and need to own that story more clearly.

3. Cross-check your “story” like a paranoid person

Honestly? A little paranoia is helpful here.

Look at:

- Personal statement

- ERAS experiences descriptions

- LoR content (when you get to see it, which I know is rare)

- MSPE “summary” paragraph

Ask yourself:

- If someone skims all of this in 7 minutes, what story comes through?

- Would they describe me in consistent terms?

- Does anything sound like a completely different person wrote it about a completely different applicant?

You want “different angles on the same person,” not “three entirely different applicants sharing one AAMC ID.”

How Much Mismatch Is Normal?

This might help your brain chill out a bit.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Minor wording differences | 80 |

| Early specialty shifts | 65 |

| Academic vs community wobble | 50 |

| Strong specialty contradiction | 35 |

| Character/behavior conflict | 10 |

Translation (rough, but realistic from what I’ve seen/heard):

- Minor phrasing differences? Almost everyone has them.

- Early shifts in specialty interest? Common, usually excused.

- Academic vs community “I love both”? Seen as fuzzy but not fatal.

- Strong specialty contradiction in the same cycle? Noticeable, sometimes costly, especially for ultra-competitive fields.

- Character or behavior contradictions? Rare but serious red flags.

You’re probably not in the bottom category. Your brain just likes to pretend you are.

A Few Concrete Examples (So You Can Reality-Check Yourself)

Example 1: EM vs IM

You: applying to EM

PS: entirely EM-focused

Letters: 3 EM, 1 IM

IM letter: “They told me they’re also considering IM.”

Most EM programs: “Ok, fine. People wavered. Their EM letters are strong. Whatever.”

Example 2: “I Love Research” vs “They Prefer Clinical Work”

PS: “I plan to build a career as a physician-scientist.”

Letters: None mention research. One says, “They told me they don’t see themselves in a research-heavy role.”

Academic program faculty: “So… which is it? Are they just saying ‘physician-scientist’ because they think we want to hear that?”

That doesn’t necessarily get you rejected. It just lowers the “fit” vibe for hard-core research programs. But a mid-tier or community-facing program might like you just fine.

Example 3: True Character Conflict

PS: “I value professionalism and always put patients first.”

Letter: “They had a professionalism concern during the rotation, arriving late multiple times and deflecting responsibility when confronted.”

This is the nuclear category. If that’s your situation, we’re not talking about “story mismatch” anymore. We’re talking remediation, explanation, damage control, and very targeted advising.

But most people reading this? That’s not your scenario. You’re dealing with narrative noise, not character assassination.

Visualizing How the Pieces Fit Together

Sometimes it helps to see the whole thing as a process, not a random judgment.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Read Personal Statement |

| Step 2 | Scan Letters of Rec |

| Step 3 | Check MSPE/Deans Letter |

| Step 4 | Positive Overall Impression |

| Step 5 | Minor Doubt, Still Consider |

| Step 6 | Flag or Lower on Rank List |

| Step 7 | Offer Interview or Higher Rank |

| Step 8 | Reject or Low Rank |

| Step 9 | Story Mostly Coherent? |

Your goal isn’t perfection. It’s just to stay in the “Positive” or “Still Consider” lanes.

You can absolutely still match with some mismatch. People do. Every single year.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Will one “off” letter ruin my entire application?

Very unlikely. If three letters and your MSPE describe you similarly and one is slightly off in direction or emphasis, most programs mentally average things out. They assume different attendings see different sides of you. One weird letter only becomes a major problem if it’s actively negative or directly contradicts your entire application theme in a way that looks dishonest.

2. What if I told a letter writer I wanted a different specialty than the one I ended up applying to?

That happens more than you think. If the letter is otherwise strong and you’ve clearly shifted direction since then (clerkships, sub-I’s, activities now match the new specialty), many committees will shrug it off as a normal evolution. If you’re worried, be ready to explain the change clearly and calmly during interviews: what changed, when, and why this new specialty fits better.

3. Programs don’t really read every letter closely… right?

Some do. Some don’t. And you don’t get to choose which is which. Usually, someone on the committee skims every letter, and for borderline candidates, letters can become more important. Don’t bank on “they won’t notice.” Assume a tired but reasonably smart human will read enough to catch obvious contradictions. Your job is to minimize those contradictions, not roll the dice.

4. If I have to reapply, should I completely scrap my old personal statement and letters?

You should definitely re-evaluate them. If the mismatch came from vague or generic statements, you need a sharper, more specific PS that actually matches your actions and goals. For letters, try to get new ones that clearly support your current specialty and direction. Don’t just reuse old letters that sell a different version of you. Reapplicants actually have one advantage: you can tell a very clear, honest story about how your direction solidified over time — as long as your documents finally agree with each other.

Key points to hang onto:

- Mismatch between your personal statement and letters is common and usually survivable if it’s about direction, not character.

- Programs want a coherent, believable story — not perfection. A mostly-aligned application with small inconsistencies will still get interviews.

- If you re-do anything in the future, make your letter writers and your personal statement actually talk to each other. Same human, same story, different angles. That’s what lands.