The biggest lie in physician-owned office buildings is this: “We’re all going to get rich together.”

You won’t all get rich. A few people will. And unless you understand exactly how these deals are structured, you’re not going to be one of them.

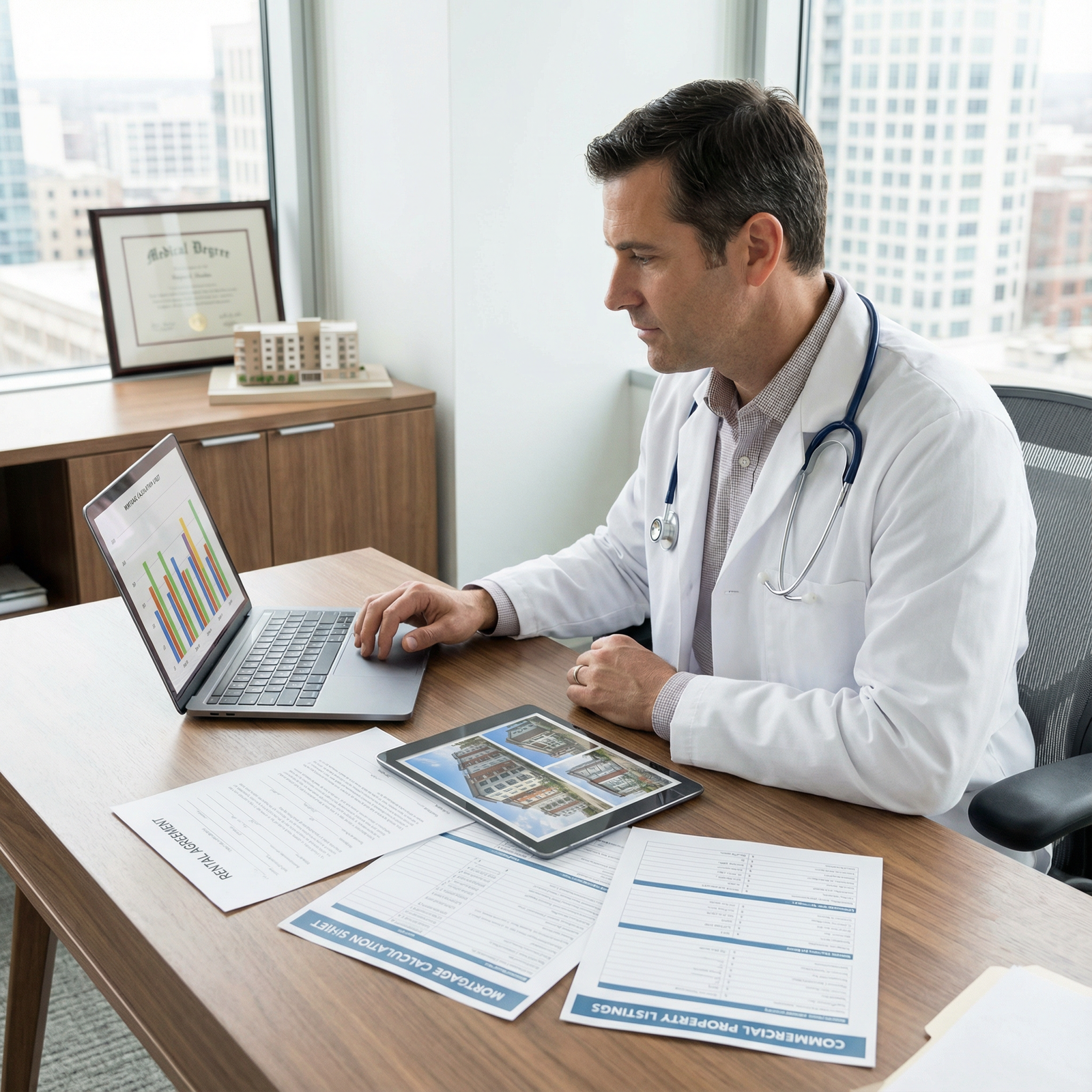

I’ve sat in those partner meetings. I’ve seen the pitch decks “prepared by our trusted developer partner.” I’ve watched junior docs sign subscription agreements they didn’t read, confident that “the senior guys have done this before.” Then five years later they realize the developer, the founding partners, and the management company made out well—while their own “equity” barely beat an index fund.

Let me walk you through what really happens behind the scenes with physician-owned office buildings, who actually profits, and how to stop being the patsy at the table.

The Real Profit Stack: Who Gets Paid First

Before a single dollar of “profit” gets to you as a physician-investor, several other mouths get fed. Consistently. Contractually. Whether the building performs or not.

Here’s the hierarchy nobody explains clearly at the first investor dinner.

| Position in Line | Party | Typical Form of Payment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lender | Interest + principal |

| 2 | Developer/Sponsor | Development fee, promotes, asset fees |

| 3 | Property Manager | Management & leasing fees |

| 4 | Senior/Founding Partners | Better terms, early entry, promotes |

| 5 | Rank-and-file Physician Investors | Dividends, appreciation (if any) |

The bank gets paid first. Always. Then the developer and affiliated entities (asset management, property management, leasing, construction management) skim fees off the top. Then any preferred returns. Then whatever’s left trickles down to you.

If you do not know exactly what the sponsor and their affiliates are earning and when, you’re flying blind.

Developer-Driven vs Physician-Driven: Two Very Different Worlds

Most “physician-owned” buildings fall into one of two buckets:

- Developer-driven deals with physicians as capital and tenants

- Physician-driven deals where the doctors truly control the asset

The difference in long-term wealth is massive.

Developer-Driven: The Pretty PowerPoint and the Quiet Fee Machine

This is the most common scenario:

A regional medical office developer approaches a large practice or hospital-affiliated group. They propose a new Class A medical office building near the hospital campus. They say the magic words: “You’ll be owners instead of paying rent to someone else.”

The pitch feels flattering. “You’re sophisticated doctors, you should be building equity.” There’s often a steak dinner. A glossy pro forma. A 6–8% projected cash-on-cash return. A 15–20% IRR “target.”

What is usually not explained in plain language:

The developer is collecting:

- A development fee (often 3–5% of project cost)

- A construction management fee

- An asset management fee annually

- A promote (carried interest) on profits above a certain hurdle

- Sometimes a leasing fee and property management fee via related entities

The cash-on-cash return you see is after you put in the risk capital, but before they tell you how much they already took off the table through fees.

The physicians are usually:

- Last in line on liquidity events

- Locked into long-term leases that guarantee the building’s income, which backs the developer’s financing and justifies their fee stack

In other words, you provide the patients, the rent stream, and the reputation. They pull the levers and skim the cream.

I’ve seen deals where the developer had their full development fee and some asset management fees collected before the building ever hit stabilized occupancy—while the physician investors were still waiting for their first distribution.

Physician-Driven: Rare, Boring… and Actually Profitable

Then there’s the less sexy, far more lucrative model. The physicians control the entity. They may hire a developer as a vendor, not as a partner. They:

- Control the LLC or partnership

- Select the lender

- Negotiate the construction and development agreements

- Hire (and can fire) the property manager

- Approve all leases, including their own

This requires a few unglamorous things:

- Boring governance structures

- Real legal work by a physician-side attorney

- Someone in the group who actually understands pro formas, cap rates, and loan covenants

These practices quietly build serious net worth. They’re not on podcasts bragging about “passive real estate wealth.” They’re renewing leases at below-market related-party rents when they want to keep distributions high, or bumping rents toward market when it’s time to maximize valuation for a refinance or sale.

They’re the ones whose “cost basis” in their condo or share was $200–300/sq ft ten years ago in a decent market, and now replacement cost is $500–600/sq ft. Their equity multiple is not theoretical. It’s in their balance sheet.

The Hidden Levers: Where the Real Money Is Made

The truth is, the biggest profits in physician-owned buildings do not come from your quarterly distribution checks. Those are the crumbs designed to keep you feeling good.

The real money comes from four levers.

1. Development Spread and Fee Extraction

This is the developer’s playground.

They secure land and build for, say, $350/sq ft all-in. When stabilized, similar medical office buildings are trading at a cap rate that implies ~$475/sq ft value. There’s a built-in 30–40% development spread.

Who captures that?

In a developer-driven deal:

- They lock in a higher development fee because they “took entitlement and leasing risk”

- They may pre-sell the building to a REIT or institutional buyer at completion or shortly after stabilization

- They roll their promote and equity into the new entity; physicians get modest returns but miss the real upside

In a physician-driven deal:

- The physicians can choose not to sell at stabilization

- They can refinance, pull out some equity tax-efficiently, and keep the asset

- The development spread accrues largely to them

2. Control of Rent Levels and Lease Terms

This is where physician-owners get played if they’re naive.

Two common patterns:

Overpaying rent to “juice” returns

The developer structures your lease at the high end of “market,” sometimes slightly above. This inflates the pro forma NOI and the appraised value, which makes the development look like a home run.You’re told, “It’s okay—you’re paying rent to yourselves.”

No. You’re paying rent to all owners, including the developer and non-clinical investors. And you’ll pay it for 10–15 years.Long, rigid leases that protect the building, not you

Complicated escalation clauses, operating expense pass-throughs, and penalties for shrinking space. These protect the building’s value for the sponsor and lender. Your practice flexibility is sacrificed to preserve NOI.

When physicians actually control the building, they do things differently:

- Lock in reasonable base rent with fair but not aggressive annual bumps

- Give themselves realistic renewal options

- Align space expansion/contraction rights with their practice growth or consolidation plans

3. Refinance Events: The Quiet Payday

This is where the insiders cash out without “selling.”

Picture this:

- Building cost: $20M

- Loan: $14M

- Physician equity: $6M

Five to seven years later:

- Stabilized NOI is strong

- Market cap rates are favorable

- New appraised value: $28M

They refinance at 65% LTV:

- New loan: $18.2M

- Old loan payoff: $12.5–14M (depending on amortization)

- Cash-out proceeds: $4.2–5.7M split by ownership share

Now a chunk of your original equity just came back to you—often tax-deferred—while you still own the building.

Here’s the catch:

Who controls the decision to refinance, and how are the proceeds split?

In many developer-sponsored deals, the promote structure gives the sponsor a disproportionate share of proceeds above the preferred return. You put in more capital and took operating risk for years; they manage the refinance and grab a big piece of the upside.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Lender Interest & Principal | 45 |

| Developer & Affiliates Fees | 25 |

| Doctor Tenants as Rent Payers | 20 |

| Investor Distributions & Equity | 10 |

That pie is ugly when you realize you’re on both the “Doctor Tenants as Rent Payers” slice and the “Investor Distributions” slice—but not really sharing in the fee stack.

4. Exit Timing and Who Decides to Sell

Final wealth is defined by one thing: who decides when to sell and at what price.

Program directors talk about “graduation rates”; real estate sponsors talk about “exit IRR.” Both can be gamed by choosing when people exit.

Look for language in your operating agreement like:

- “Sponsor has the right, but not the obligation, to cause a sale of the property…”

- “Investors agree to cooperate with any sale recommended by the sponsor…”

- “Drag-along rights…”

I’ve seen physicians forced into selling at the first decent offer because:

- The sponsor’s promote gets triggered at exit

- The fund life or investment horizon requires a sale

- The sponsor wants to recycle capital into their next project

Your practice might have been better off holding the building for another cycle. But your interests are misaligned with the sponsor’s fund timeline.

The Legal Fine Print: Where You Either Win or Bleed

You don’t need to become a real estate attorney. But you’d better understand where the landmines are. Because they’re always in the same places.

Operating Agreement: Who Actually Runs the Show?

The operating agreement is where your “ownership” either means something or is a participation trophy.

Red flags that you’re just along for the ride:

- Sponsor/manager has unilateral authority to:

- Refinance

- Sell the building

- Replace property managers

- Enter into leases (including with your own practice)

- Physician investors are “limited partners” with:

- No real voting rights on major decisions

- No ability to remove the manager except for extreme fraud

Translation: you have economic exposure but almost no control. You are equity without power.

On the other hand, a physician-controlled building will usually have:

- A board or management committee with physician majority

- Defined voting thresholds for sale, refinance, major leases

- Minority protection provisions so a few big players cannot completely steamroll everyone else

Capital Calls and the Quiet Dilution Game

Developers love two things:

- Soft physicians who will bail out a deal with additional equity

- Structures that punish anyone who can’t write another check

Capital call provisions are standard. The trick is in the penalty.

Common approaches that can crush you:

- Defaulting investors’ interests get heavily diluted

- Sponsor has the right to loan money at above-market interest and convert to equity

- New capital comes in with senior preferred terms above existing equity

This matters in real life. Imagine a building overruns its construction budget by 8–10% (happens all the time). Another $1–2M is needed. You’re in year 3 of practice with loans and maybe a new baby. The founding partners and sponsor can write another $200–300k check. You can’t.

You don’t lose your whole stake, but your ownership drops, your preferred returns get subordinated, and your upside disappears.

Related-Party Transactions: Where Margins Quietly Vanish

Ask one simple question in every deal:

“List all related-party relationships and who benefits from each.”

If the answer is hand-wavy or defensive, walk.

Common places money leaks out via affiliates:

- Property management company (often owned or co-owned by sponsor)

- Leasing brokerage

- Maintenance or construction companies

- Insurance brokerage

- Even janitorial services in some smaller markets

A good, fair deal can still have related parties. But the fees should be market-rate and fully disclosed, and you should have the right to replace them if performance is poor.

Who Actually Profits: Three Archetypes

Let me be blunt. In most physician-owned office building stories, the characters sort roughly into three categories.

1. The Sponsor/Developer: The House Always Wins

They profit from:

- Guaranteed development and management fees

- Promote structures on the back end

- Ancillary service companies

- Recycling capital into new deals using your building as a track record

Their risk is front-loaded but well-hedged.

Your risk is long-term and patient-dependent.

2. The Senior “Anchor” Physicians: If They’re Smart, They Win

The founding partners with:

- The largest spaces

- Longest lease commitments

- Early-bird equity at lower valuations

They can do very well when:

- They negotiated real governance rights

- They locked in reasonable rents from the start

- They had a real say in who the sponsor was and how the deal was structured

I’ve seen ortho groups where the original four partners each put in $250k fifteen years ago, built their own building, refinanced twice, and now each has >$2–3M of equity in the property plus years of healthy distributions. That’s doing it right.

3. The Late-Joiner Physicians: Often the Bag Holders

These are the new associates or later buy-ins who:

- Pay to “buy into the building” at a much higher valuation

- Inherit long-term lease obligations they never negotiated

- Have little influence over refinance or sale decisions

Their IRR is usually mediocre. They’re told it’s “part of being a partner.” In truth, a lot of the appreciation is already baked in and captured by the earlier cohort.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Developer | 18 |

| Founding Physicians | 12 |

| Later-Join Physicians | 6 |

Those numbers are not gospel, but they’re directionally accurate for many deals I’ve seen.

How to Not Get Screwed (Without Becoming a Full-Time Landlord)

You don’t have to reject every physician real estate opportunity. But you do need to stop approaching them like another “investment on the side.”

Here’s the quiet reality: the physicians who do well with office buildings treat it like a business venture, not some passive syndication they glanced at on their phone.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Offered ownership |

| Step 2 | Hire real estate attorney |

| Step 3 | Walk away |

| Step 4 | Model best and worst case returns |

| Step 5 | Invest with eyes open |

| Step 6 | Developer led or Physician controlled |

| Step 7 | Full fee and promote disclosure? |

| Step 8 | Governance and capital call fair? |

| Step 9 | Still acceptable? |

You’ll notice the “walk away” branch shows up a lot. That’s intentional. Most of these deals are designed so the sponsor must get paid, but you might get paid.

If you’re going to play, you need to know the game you’re playing.

Case Study: Two Buildings, Same Doctors, Opposite Outcomes

Let me give you a composite story I’ve seen versions of in multiple markets.

Same large multi-specialty group. Two buildings, ten years apart.

Building A (Developer-Sponsored, 2010)

- Class A medical office, 60k sq ft

- Developer brings land, plans, and lender

- Physicians commit to ~60% pre-leased space

- Developer charges 4% development fee, 1% annual asset management fee, and a 20% promote above an 8% preferred return

Outcome:

- Stable building

- 5–7% annual cash returns to physicians

- After 10 years, building sold to a REIT

- Physicians roughly double their money over a decade

- Developer uses track record to raise their own MOB fund; collects millions in fees and promote

Building B (Physician-Controlled, 2020)

- Same group, older docs now wiser

- They form their own LLC, hire a development consultant on a flat fee

- They select GC and negotiate contracts themselves (with real legal help)

- They pay fair property management fees to a third party, with a right to terminate

- No promote structures. Just pro-rata ownership based on capital.

Outcome (projected, based on conservative numbers actually in their docs):

- 6–8% annual cash return once stabilized

- Refinance projected at year 7 with substantial equity return

- Long-term hold with ability to adjust rents as the group grows or consolidates

The IRR difference doesn’t look dramatic on paper—maybe 12% vs 16% on sponsor pro formas. But the control difference is massive. And over 15–20 years, that’s millions of dollars staying in physician pockets instead of subsidizing a developer’s next luxury condo project.

Quick Reality Check: Your Time vs Your Money

You went into medicine, not real estate development. So there’s always this internal negotiation: “Do I want to spend my energy on this?”

That’s fair. But answer honestly:

- Would you sign a 15-year employment contract you didn’t read, with RVU targets, tail coverage clauses, and restrictive covenants “explained” by the employer’s lawyer?

- Then why are you signing a multi-million-dollar real estate deal with 150 pages of operating agreements and loan terms you’ve barely scanned?

You do not need to become a real estate guru. But you do need:

- A physician-side real estate attorney who’s not afraid to blow up a bad deal

- Enough literacy to ask the right questions about fees, control, capital calls, and exit rights

- The backbone to walk away when the answers are vague, rushed, or patronizing

Because here’s the truth: there will always be another deal. There will not always be a chance to undo a bad one.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Year 0 | -100 |

| Year 1 | 2 |

| Year 3 | 5 |

| Year 5 | 7 |

| Year 7 | 10 |

| Year 10 | 15 |

FAQs

1. Is investing in my group’s office building ever actually a good idea?

Yes, it can be excellent—if the structure is aligned. When physicians truly control the entity, the rents are reasonable, the fee stack is modest and transparent, and governance is fair, these buildings can be one of the best long-term wealth builders you’ll ever touch. Your clinical practice literally drives the value of the asset. But that’s precisely why you should be allergic to structures where you bear the risk as a tenant and investor, yet outsiders siphon off the upside.

2. What’s the single biggest red flag in a physician real estate deal?

Lack of clear, written disclosure of all fees and promotes to the sponsor and affiliates. If you ask, “Can you show us a full breakdown of every way you’re getting paid on this deal, from development through sale?” and you get a 30,000-foot answer, you already have your answer. Anyone who’s proud of fair compensation will show you in writing, in detail. Anyone who’s hiding something will rush, deflect, or guilt-trip you about “holding up the opportunity.”

3. Should I ever join a deal where I’m a small minority investor with no control?

Sometimes, but only if the economics are clearly in your favor even assuming zero control. That means: conservative leverage, transparent fee structure, strong tenant base, reasonable rents, and a sponsor with a track record you can verify. If the IRR only looks attractive because they’ve dialed rents to the moon and assumed cap rates that belong in a fantasy novel, pass. If you’re going to be purely along for the ride, at least make sure it’s not a ride sponsored by wishful thinking.

4. How much of my net worth should I put into these physician-owned buildings?

For most practicing physicians, total illiquid private real estate (including your surgery center, office building, and any syndications) should generally sit in the 10–25% of net-worth range. Push much past that and you’re betting heavily on local real estate cycles and your own practice stability. Remember: your human capital is already concentrated in healthcare. Don’t double-down blindly with 70% of your financial capital in the same ecosystem and two ZIP codes.

Years from now, you won’t remember the brochure renderings, the glossy pro formas, or the steak dinner where everyone nodded along. You’ll remember whether you were the one quietly collecting distributions from an asset you truly controlled—or the one wondering how everyone else seemed to get rich off the same building you’ve been paying rent to for a decade.