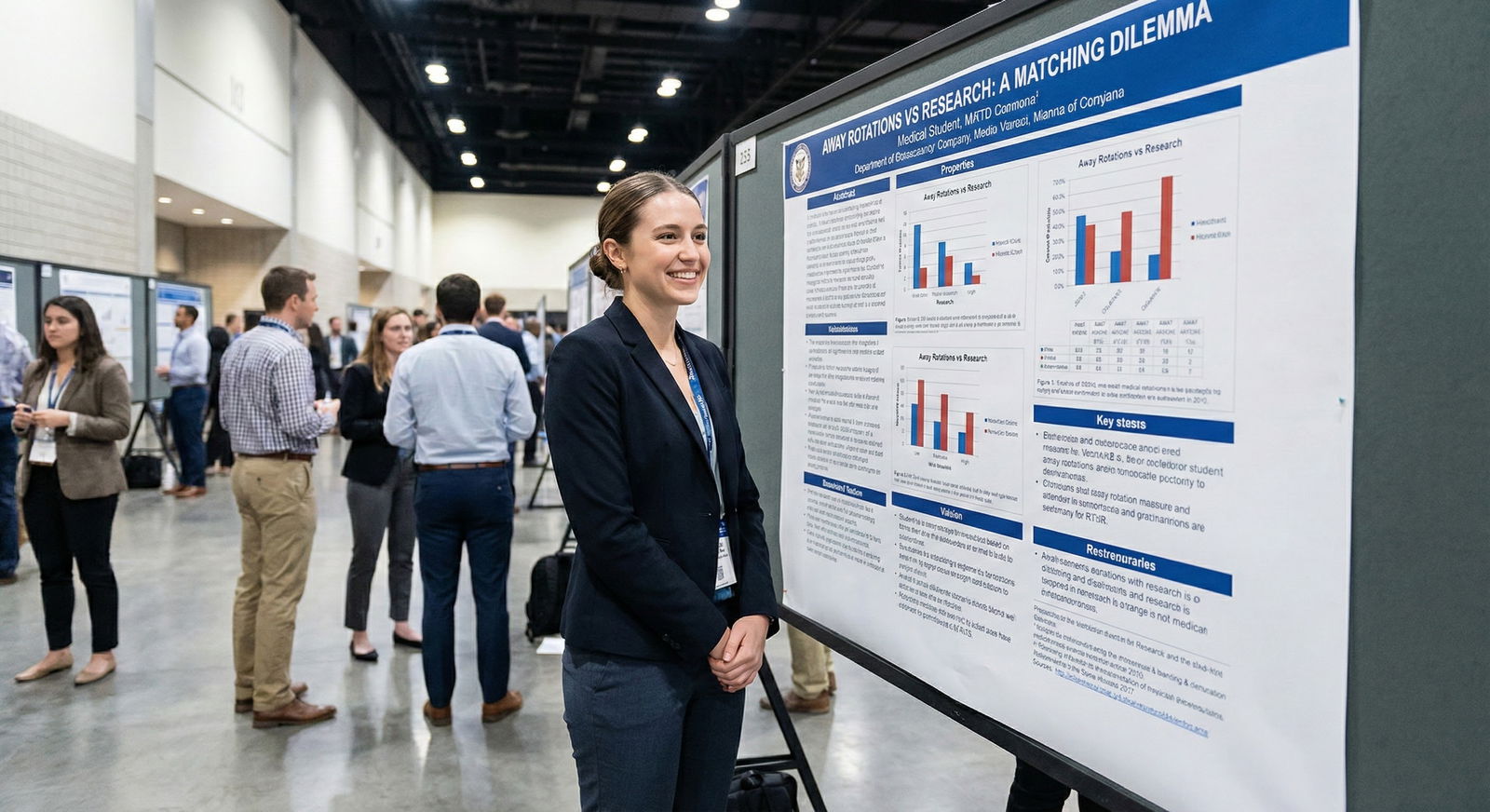

You are staring at your ERAS “Scholarly Activities” section. One tab reads “Publications.” The next tab: “Presentations / Posters.” You have med school research day posters, a few regional talks, maybe one national oral presentation, and you are not sure what is actually impressive versus just... there. And you know programs care, but no one has ever really explained the hierarchy or how to format this in a way that does not look amateur.

Let me break this down specifically.

You are not just listing “stuff you did.” You are signaling:

- How serious you are about academic work

- How far your work traveled (local vs national)

- How often you got to be “the face” of the project (first author, presenting author, invited speaker)

- How well you understand academic norms

Most applicants underutilize this section the same way: random ordering, sloppy formatting, no clear separation of levels of prestige. That costs you.

We are going to fix that.

1. The Real Hierarchy: What Actually Impresses PDs

Forget the vague “all research is good” reassurance you get from advisors. In practice, program directors and academic faculty mentally rank your presentations and posters in a rough hierarchy, even if they never say it out loud.

1.1 The Core Hierarchy of Presentations

From strongest to weakest academic signal:

Invited plenary / named / keynote talks at national or international meetings

Rare for a student or resident, but if you have one, it goes at the top of the mountain. This is not “I submitted an abstract and got a talk.” This is “I was invited by the conference or society to deliver a major lecture.”Oral abstract presentations at national or international conferences

Example:- ASCO oral presentation

- ATS podium talk

- American Academy of Neurology platform presentation

These often mean your abstract was competitively selected from a large pool. They are not casual.

Oral presentations at regional or major institutional meetings

Examples:- State ACP meeting talk

- Regional specialty society oral presentations

- Institutional research symposium where top abstracts get podium spots

Poster presentations at national or international meetings

This is the bread and butter for strong academic applicants. Not as prestigious as oral, but still meaningful, especially if you are first author.Poster presentations at regional, state, or institutional research days

Med school research day. Department research symposium. State ACP poster. These are still helpful, but the bar to acceptance is usually lower. Stronger when they represent early steps that later led to national work.Unpresented or internal “presentations” that never left your home institution

Example: a QI project presented in a noon conference that never went to a formal meeting. This is the bottom tier, but can still be included, especially if it is your only work or if it led to implementation changes.

Now, that is for abstracts and research dissemination.

1.2 Separate, but Related: Educational and Invited Talks

Do not confuse research abstracts with another category that also matters:

- Invited grand rounds or departmental lectures

- Formal teaching sessions you were asked to give (e.g., M&M, board prep sessions)

- Curriculum-based talks you led (with formal audience and structured content)

These are not “abstract presentations” but they show academic engagement and teaching ability. They usually belong in a separate section: “Invited Talks / Lectures” or “Educational Presentations.”

1.3 How Programs Actually Weigh This (Reality Check)

Here is how most PDs read your presentation section:

- They skim the venue names (national recognizes national).

- They look for first author and presenting author.

- They quickly note field alignment (is your work relevant to our specialty?).

- They get an impression of consistency (one random poster vs multiple years of output).

Nobody is manually scoring you on a rubric. But “3 first-author oral presentations at national meetings” lights up their pattern recognition. Versus “local student research day poster” which is fine, but not the same.

2. Types of Presentations: Know What You Are Actually Listing

Before you format anything, you need to categorize correctly. Most CVs mix all of this together, which looks unsophisticated.

2.1 Abstract-Based Presentations

These are tied to scientific abstracts that were submitted, peer-reviewed (at some level), and accepted to a meeting:

- Oral platform presentations

- Plenary abstracts

- Poster presentations

- Rapid-fire oral/poster hybrids (some specialties use these)

These belong under a heading like:

- “Abstracts and Presentations”

- “Scientific Presentations”

- “Conference Presentations”

Do not bury them under random “Activities.”

2.2 Educational / Invited Presentations

Not based on novel research, but still formal and academic:

- Grand rounds

- Departmental invited lectures (e.g., “Update in Heart Failure Management” for hospitalists)

- M&M conferences where you were the designated presenter

- Invited teaching sessions at other institutions (e.g., visiting lecture at an affiliated hospital)

These do not need an abstract; they are still CV-worthy.

You can group them as:

- “Invited Lectures and Educational Presentations”

- “Teaching Presentations”

2.3 Internal Talks, Journal Clubs, and Small-Group Teaching

The honest truth:

- One-off journal club as an MS3: not impressive by itself.

- Routine student “present your H&P” sessions: not CV material.

But:

- If you organized and ran a journal club series for a year, that is leadership and education.

- If you designed a curriculum and repeatedly taught a specific topic, that can be formatted as education/teaching experience, not as “presentations.”

Do not pad your CV with every time you put up a PowerPoint. That reads as insecurity.

3. The Ordering: How To Structure This on a Residency CV

You are building a CV for the residency match. The structure matters as much as the content.

3.1 Global Ordering Principles

Apply these rules:

- Group by category, not by date alone.

- Within each category, order most prestigious → least, and then by reverse chronological date.

- Maintain consistent formatting across every entry.

A clean structure for a research-inclined applicant:

- Publications

- Submitted / In-Revision Manuscripts (clearly labeled)

- Abstracts and Scientific Presentations

- Invited Lectures and Educational Presentations

- Quality Improvement and Implementation Projects (if presentation-based)

For a less research-heavy applicant, you might collapse a bit:

- Publications and Abstracts

- Presentations and Posters

- Teaching and Educational Activities

Just do not throw talks under “Other” like you do not care about them.

3.2 Within “Abstracts and Presentations”: Ranking Strategy

Inside your presentations section, use subheadings to make the hierarchy explicit.

For example:

Abstracts and Presentations

- Oral / Platform Presentations

- Poster Presentations

- Local and Institutional Presentations

Under each, order newest to oldest.

If you have mostly posters, you can keep it simpler:

Abstracts and Presentations

- National and International Meetings

- Regional and Institutional Meetings

You are making it easy for tired PDs to see your strongest work first.

4. Exact CV Formatting: How a Proper Entry Should Look

Here is where most students ruin perfectly good content with sloppy formatting. You want your entries to look like they came from someone who understands academic medicine.

4.1 Core Template for Abstract-Based Presentations

Use a modified journal-citation style:

Author(s). Title. Conference name; conference type; city, state (or city, country if international); month year.

Key rules:

- Your name in bold, always.

- List authors in the actual order they appear on the abstract.

- Include the meeting name spelled out on first use, with abbreviation optional in parentheses if it is a major one.

- Clarify oral vs poster in the entry.

Example – national oral abstract:

Smith J, Patel R, Nguyen T, Lee A. Impact of early palliative care on ICU readmissions in advanced heart failure. American College of Cardiology (ACC) Scientific Session; Oral abstract presentation; Chicago, IL; March 2025.

Example – national poster:

Smith J, Brown L, Ahmed S, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis adherence in hospitalized medical patients. American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting; Poster presentation; Atlanta, GA; December 2024.

Example – local institutional poster:

Smith J, Rodriguez M, Chen D. Implementation of a resident-led sepsis early warning protocol in the MICU. University Hospital Research Day; Poster presentation; City, State; May 2024.

4.2 Indicating Presenting Author vs Just Coauthor

If you were the presenting author, state it explicitly. That matters.

Add at the end:

- “(Presenting author.)” or

- “(First author and presenting author.)”

Example:

Smith J, Patel R, Nguyen T, Lee A. Impact of early palliative care on ICU readmissions in advanced heart failure. American College of Cardiology (ACC) Scientific Session; Oral abstract presentation; Chicago, IL; March 2025. (First author and presenting author.)

This clarifies that you were not just name #7 who never left campus.

4.3 Formatting Invited or Educational Talks

Different structure. No abstract. Focus on role and topic.

Template:

Your Name. Title of talk. Name of event or series; Invited lecture / Grand rounds / Educational session; Institution; City, State; Month Year.

Example – grand rounds:

Smith J. New frontiers in anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. Department of Medicine Grand Rounds; University Hospital; City, State; September 2024. (Invited lecture.)

Example – educational series:

Smith J. High-yield EKG interpretation for junior residents. Resident Board Review Series; Internal Medicine Residency Program, Community Medical Center; City, State; January 2024.

You can optionally tag teaching level if it helps (e.g., “Audience: internal medicine residents and medical students”), but keep it brief.

5. ERAS vs Traditional CV: How to Not Get Burned

You are dealing with two slightly different beasts:

- The formal CV you might send to a mentor, fellowship program, or upload as a PDF.

- The ERAS “Experiences” and “Scholarly Activities” sections with rigid fields.

5.1 ERAS Presentation Input Strategy

On ERAS, you will often encounter fields like:

- “Type: Poster / Oral Presentation / Other”

- “Title”

- “Authors” (sometimes)

- “Name of Conference or Meeting”

- “Date”

Your goals:

- Keep the title verbatim from the abstract. Do not embellish it.

- Use the standard meeting name, not your school’s internal nickname.

- Include all authors, with your name bolded in your personal CV, but on ERAS you cannot bold – you can instead write: “Authors: Smith J (presenting), Patel R, …” in the description field if allowed.

- In any free-text description, clarify “Oral presentation” or “Poster presentation,” and, where relevant, “Selected for oral presentation from X submitted abstracts” if that is specifically stated by the meeting (do not invent this).

5.2 Matching Your PDF CV to ERAS Entries

There is nothing more annoying to reviewers than seeing a glowing “national talk” on your PDF CV that does not appear anywhere in ERAS activities, or vice versa. It smells sloppy.

The fix:

- Maintain a master CV in Word/Google Docs.

- Every time you add an item to ERAS, you mirror it on your CV with the same title, date, and venue.

- If something is pending (abstract accepted, conference upcoming), label it correctly: “Accepted for presentation” with future date.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Do project |

| Step 2 | Submit abstract |

| Step 3 | Track internally only |

| Step 4 | Present at meeting |

| Step 5 | Add to master CV |

| Step 6 | Add to ERAS |

| Step 7 | Update if later published |

| Step 8 | Accepted? |

6. Handling Common Edge Cases (Where People Usually Mess Up)

There are patterns I see over and over that hurt otherwise good applications. Fix them now.

6.1 Same Project, Multiple Presentations

You presented the same project:

- At your med school research day

- Then at a state society meeting

- Then at a national conference

Do you list all three? Yes – but carefully.

Use separate entries for each presentation, because each acceptance is distinct. However:

- Use the exact same title unless the official abstract title changed.

- Make it possible for a reader to infer this is one evolving project, not three unrelated ones.

Example (ordered highest to lowest):

Smith J, Brown L, Ahmed S, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis adherence in hospitalized medical patients. American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting; Poster presentation; Atlanta, GA; December 2024.

Smith J, Brown L, Ahmed S, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis adherence in hospitalized medical patients. State American College of Physicians (ACP) Scientific Meeting; Poster presentation; State Capital, State; October 2024.

Smith J, Brown L, Ahmed S, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis adherence in hospitalized medical patients. University School of Medicine Research Day; Poster presentation; City, State; May 2024.

Do not rename the project each time to make it look like three different studies.

6.2 Accepted but Not Yet Presented

If an abstract is accepted but the conference is in the future:

Format it as:

Smith J, … Title. Meeting name; Poster presentation (accepted; scheduled for presentation June 2026); City, State; June 2026.

Or in a shorter variant:

… Poster presentation (accepted for presentation).

Be honest. Do not write as if it already happened.

6.3 Virtual Conferences

Post-COVID, many meetings went virtual. Programs understand this. You still list them.

Template:

… Meeting name; Poster presentation (virtual); June 2023.

If there was no city, you can omit that, or simply state: “Virtual conference.”

6.4 Industry or Non-Traditional Venues

If you gave a talk for an industry-sponsored dinner or at a non-academic venue, you can list it, but:

- Put it under “Other Presentations” or “Educational Presentations,” not scientific abstracts.

- Disclose if clearly industry-sponsored (it is not a black mark, just do not hide it).

7. Visualizing the Hierarchy and CV Placement

Here is a compact view of perceived strength and where things go.

| Type | Typical Strength | CV Section |

|---|---|---|

| National invited plenary/keynote | Very high | Invited Lectures / Major Presentations |

| National oral abstract | High | Abstracts and Scientific Presentations |

| National poster | Moderate-High | Abstracts and Scientific Presentations |

| Regional oral | Moderate | Abstracts and Scientific Presentations |

| Regional/institutional poster | Moderate | Abstracts and Scientific Presentations |

| Internal teaching / grand rounds | Moderate | Invited Lectures / Educational Present. |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| National plenary/keynote | 100 |

| National oral abstract | 85 |

| National poster | 70 |

| Regional oral | 60 |

| Regional poster | 50 |

| Institutional poster | 40 |

| Routine journal club | 10 |

You are not gaming the system. You are just presenting the reality of your record in a way that reflects how programs actually think.

8. Optimizing When You Feel “Light” on Presentations

Suppose you are an MS4 with:

- One med school poster

- One institutional QI day presentation

- A few journal clubs

You are not doomed. But you need to format intelligently.

8.1 Do Not Inflate, But Do Consolidate

Instead of seven weak lines like:

- “Presented journal club on X”

- “Presented topic Y at noon conference”

- “Led presentation on Z in small group”

You bundle:

- Routine teaching activities under “Teaching Experience” (one entry with description and dates)

- Formal research/QI posters under “Abstracts and Presentations” (even if only 1–2)

For example:

Teaching Experience

Small Group and Conference Teaching, University School of Medicine; City, State; 2023–2024.

Prepared and delivered multiple 30–45 minute educational sessions on internal medicine topics for third-year medical students and peers, including journal club discussions, EBM workshops, and case-based noon conferences.

Then:

Abstracts and Presentations

Smith J, … Title. University School of Medicine Research Day; Poster presentation; May 2024.

This reads as honest, compact, and mature.

8.2 If You Have Many Low-Level Items

If you really do have dozens of internal QI talks or repeated sessions of the same curriculum, you can:

- Use a line like “Presented this session 6 times per year to rotating resident cohorts” in a description.

- Avoid listing each individual date and audience separately, unless asked.

9. Specialty-Specific Nuances (Brief but Important)

Not all fields treat presentations the same way.

- Road specialties (Derm, Plastics, Ortho, ENT) care a lot about research and national presentations. They expect multiple national posters; oral talks are gold.

- Academic-heavy specialties (Onc, Cards, Pulm/CC) love seeing national society meetings on your list.

- Primary care / community-oriented programs still appreciate posters but are more forgiving if you have just a few, especially when offset by strong clinical narratives, leadership, or service.

Do not panic if your list is modest. Just make sure it is clean, honest, and appropriately framed.

10. Common Formatting Mistakes That Scream “Amateur”

Let me be blunt. These are red flags:

- Using different formats for each entry (punctuation, ordering, or detail all over the place)

- Not listing locations or dates

- Not specifying poster vs oral

- Random capitalization of titles and meeting names

- Mixing invited non-research talks into the same list as research abstracts with no distinction

- Listing vague items: “Presentation at hospital” with no title, date, or context

Your CV is not a group text. It is a professional document.

A polished section should look visually uniform. When you scan it, the pattern is obvious: Author. Title. Event. Type. Location. Date. Optional role note.

11. Quick Step-by-Step: Rebuilding Your Presentations Section Tonight

If you want a concrete workflow, here it is.

Open your current CV and ERAS.

Make a separate document titled “Raw Presentations List.” Dump every talk/poster you have, no format, just bullets: title, date, where, what type.

Mark each as:

- National / International

- Regional / State

- Institutional / Internal

- Research abstract vs invited/educational

Build your headings:

- Abstracts and Scientific Presentations

- Invited Lectures and Educational Presentations

Under “Abstracts and Scientific Presentations,” create subheadings if needed:

- National and International

- Regional and Institutional

Copy entries into the right spot, starting with the highest level.

Apply one formatting template to all of them, line by line. Do not improvise per entry.

Cross-check dates and titles with your actual accepted abstract emails or conference programs.

Only after that, update ERAS entries to match exactly.

You do this once, cleanly, and your academic record will stop looking like a miscellaneous drawer.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Dump all presentations |

| Step 2 | Classify by level and type |

| Step 3 | Create headings/subheadings |

| Step 4 | Apply uniform format |

| Step 5 | Order by prestige then date |

| Step 6 | Sync with ERAS |

FAQs (Exactly 6)

1. Should I list a poster or talk if I was not first author?

Yes. Coauthored presentations still count and should be listed, especially if at national or major regional meetings. Just keep the true author order, bold your own name, and do not pretend you were first author. If you were the presenting author but not first, you can state “(Presenting author.)” at the end.

2. Is a national poster better than a regional oral presentation?

In most cases, yes. A national venue signals a higher level of reach and competition. A national poster generally carries more weight than a small regional oral. That said, both are good; you list both. The real power move is a national oral or plenary, but those are rarer at the medical student level.

3. Do residency programs actually read individual presentation titles?

Senior faculty and PDs often skim rather than read deeply. They look at venue, type (poster vs oral), and your author position. However, if a title jumps out as directly relevant to their specialty or unusually sophisticated, they may look more closely and ask about it in interviews. So your titles should be accurate and professional, but you are not writing clickbait.

4. Should I combine publications and presentations into one section?

For a serious academic trajectory, no. Keep “Publications” and “Abstracts and Presentations” separate. They represent different levels of scholarly completion. Combining them looks unsophisticated at research-heavy programs. If your record is very light, you can temporarily group them, but plan to separate them as your output grows.

5. How far back should I go? Do college posters or talks belong?

If they are directly relevant to your current specialty or clearly substantial (e.g., national scientific meetings), you can include late-college work, especially if it continued into med school. High school science fair? No. A random undergraduate class presentation? No. Filter by: Was this an academic conference or formal institutional research event? If yes and within 5–7 years, it is usually fine.

6. How do I list a project that never made it beyond internal presentation?

If it was a formal institutional presentation (e.g., departmental research day, institutional QI presentation with an official program), list it under “Abstracts and Presentations – Institutional Meetings.” If it was a routine internal talk (e.g., regular noon conference), consider folding it into a “Teaching Experience” entry instead of treating it as a research abstract. Do not dress up routine service presentations as if they were peer-reviewed national conference abstracts.

With your presentations, posters, and talks cleanly structured and properly formatted, your CV stops looking like a scattered list of tasks and starts reading like a coherent academic story. The next step is making sure you can actually discuss each of these projects intelligently on interview day—why the work mattered, what you did, and what you learned. That is the part where you move from lines on paper to someone programs want on their team. But that conversation comes next.