The biggest mistake residents make when a colleague is burning out is pretending it’s “just a tough rotation” and doing nothing. That is how people slide from tired to unsafe.

You’re not just a bystander here. You’re part of their safety net. And yours.

This is the playbook for what to actually do when a co-resident is clearly burning out—step by step, with actual scripts and realistic constraints of residency life. Not the wellness poster version.

1. Recognize What You’re Really Seeing (Not Just “Being Tired”)

You already know everyone in residency is tired. That’s not what we’re talking about.

Burnout and crisis have patterns. When those patterns show up, you need to stop hand-waving it as “we’re all struggling.”

Watch for combinations, not just single symptoms.

| Domain | Concerning Signs (Examples) |

|---|---|

| Work Behavior | Repeated late notes, missed tasks, ED call-backs |

| Cognition | Confusion, blanking on basics, near-misses |

| Mood | Irritability, numbness, hopeless comments |

| Functioning | Sleeping at desk, not eating, calling in sick |

| Risk | “Doesn’t matter”, “Patients better off without me” |

Patterns I’ve seen that should make you pause:

- The PGY-2 who used to over-prepare now “doesn’t care” and repeatedly forgets anticoag orders.

- The co-resident who starts calling out sick every post-call, then disappears to their car during downtime.

- The usually steady senior who snaps at nurses, then makes a basic insulin error and shrugs it off.

Ask yourself bluntly:

- Are they significantly different from their baseline?

- Are they becoming unreliable in a way that could hurt patients?

- Are they saying things that sound hopeless, nihilistic, or self-destructive—even as “jokes”?

If you’re asking, “Is this bad enough to worry?” it usually is.

2. Before You Act: Clarify Your Actual Goals

You’re not their therapist. You’re not program leadership. You’re a peer in the same dysfunctional machine.

So your goals have to be realistic:

- Make sure they’re not in immediate danger (to self or patients).

- Give them a safe opening to be honest.

- Help them connect to someone with power/resources (chiefs, PD, mental health).

- Reduce their workload today if it’s clearly unsafe.

- Do all of that without setting yourself on fire too.

That means:

- You don’t promise secrecy you can’t ethically keep.

- You don’t try to “fix” their life in a single conversation.

- You do take responsibility for speaking up if what you’re seeing is dangerous.

Think “bridge” not “savior.” Your job is to get them from “alone and overwhelmed” to “seen and supported.”

3. The First Conversation: How to Approach Without Making It Weird

The worst opener: “You seem really burned out, are you okay?”

They’ll say “I’m fine.” You’ll both know it’s a lie. Then door closed.

You need something lower-key, specific, and non-judgmental.

Timing and place

- Not in front of attendings, med students, or nurses.

- Not in the middle of rounds, especially if they just got demolished.

- Aim for: call room, stairwell, workroom after rounds, short walk to grab coffee.

Keep it simple: you’re concerned, you noticed changes, you’re not there to evaluate them.

Some scripts that actually work:

- “Hey, I’ve noticed you’ve been staying later and seem wiped. How’re you holding up this month?”

- “Yesterday looked brutal. How are you really doing with all this?”

- “You’ve been doing the work of three people lately. What’s your stress level at right now—like 1 to 10?”

Then shut up for a second. Let the silence sit. Do not immediately soften it with “But I’m sure you’re fine.”

If they brush it off:

- “Yeah, I get the instinct to say ‘I’m fine.’ I’ve done it. I’m just not totally buying it with what I’ve seen. I’m not judging, just checking in.”

Your job in that first conversation is not to extract a confession. It’s to signal: “I see you. I’m not scared of hearing the ugly version. I’m in your corner.”

4. Sort Out: Stressed, Burning Out, or in Crisis?

You need a quick mental triage. You’re not diagnosing. You’re deciding how urgent this is.

Here’s a simple internal flowchart.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Notice changes in co-resident |

| Step 2 | Ask how they are |

| Step 3 | Immediate escalation to chief/PD/ED |

| Step 4 | Same day talk with chief or attending |

| Step 5 | Support, suggest resources, follow up |

| Step 6 | Any safety red flags? |

| Step 7 | Severe impairment at work? |

Ask yourself (or them, if you have rapport):

Safety:

- “Have you had any thoughts of hurting yourself? Even passive like ‘I wish I wouldn’t wake up’?”

- “Any moments where you’ve felt so overwhelmed you thought, ‘I shouldn’t be doing this’?”

Function:

- “Are you making more mistakes than usual?”

- “Are you having trouble keeping track of tasks or plans?”

Capacity:

- “How are you sleeping when you’re actually off?”

- “Anything outside of work falling apart—relationships, bills, basic stuff?”

Red flag answers:

- “Sometimes I think it’d be easier if a truck hit me on the way in.”

- “I caught myself almost writing the wrong dose again yesterday and just stared at it.”

- “I can’t stop crying on the drive home, then I sit in the car 30 minutes before I can walk in.”

That’s not “regular residency misery.” That’s a problem that requires escalation.

5. When You Suspect Real Risk: How to Escalate Without Blowing Them Up

This is where residents freeze. They’re afraid:

- They’ll “ruin” the person’s career.

- They’ll be labeled dramatic.

- They’ll betray trust.

Harsh truth: if your co-resident is at the point of talking about self-harm or making repeated dangerous errors, the bigger risk is not escalating.

You can still do it in a way that respects them.

Step-by-step if you hear real red flags

Stay calm and clear with them.

- “Thank you for being honest with me. I’m not going to just leave you alone with this.”

- “Because you’re talking about [wanting to die / making serious errors], I can’t keep this only between us. But I want to involve the right person with you, not behind your back.”

Ask them who they’d prefer as first contact:

- Chief resident

- Program director (PD) or associate PD

- Trusted faculty mentor

- GME office or wellness officer, if your institution has that

Propose something specific, not vague:

- “Let’s step out and call [Chief’s name] together.”

- “I’ll text [Chief] and say we need a private call in the next hour. You don’t have to talk at first if you don’t want to, but I’ll be on with you.”

If they refuse any help and you still believe there’s real risk, you escalate anyway.

You do not promise “I won’t tell anyone” if you think they might harm themselves or are unsafe with patients.

You can say:

- “I care more about you being alive than you being mad at me. I’m going to get backup on this.”

Then you contact:

- On service? Senior/chief or attending.

- Off service or at home? Chief resident or PD.

- Immediate self-harm concern? ED and hospital security / psych consult line per your hospital’s policy.

6. If It’s “Just” Severe Burnout: Concrete Ways to Help Without Saving Them

Let’s say they’re not actively suicidal and not completely falling apart—but they’re clearly burning out hard. Crying in the bathroom, emotionally numb, cynical, running on fumes.

Here’s where you can do the most good.

6.1. Short-term, tactical support (today and this week)

This isn’t abstract “I’m here if you need anything.” That’s useless.

Make offers with edges:

- “Give me two tasks you hate on this service and I’ll take them today—labs calls, discharge summaries, whatever.”

- “I’ve already seen Bed 3 and 5; I’ll write those notes. You focus on the sick new admit.”

- “You look like you need 20 minutes to reset. I’ll cover pages while you grab coffee or sit in the call room. Set a timer and come back; I’ve got it.”

Then follow through. Do not martyr yourself into exhaustion, but small redistributions can be life-saving in a brutal moment.

6.2. Medium-term support: get them to someone with institutional power

You’re still a powerless cog. You need someone who can:

- Pull them off nights

- Adjust schedules

- Arrange medical leave

- Protect them from retaliation (in theory, at least)

Help them cross that bridge:

- “Would you be willing to talk to [Chief Name] if I’m there with you?”

- “Our PD has actually been decent about schedule adjustments when people are drowning. I can help you draft an email.”

If they’re scared of being punished:

- “You’re not asking for favors. You’re describing an unsafe situation—for you and patients. That is literally their job to handle.”

Offer to:

- Sit with them while they email.

- Be present if they talk to leadership (even if it’s just on standby in the hall).

- Co-sign the reality: “Yes, they’ve been carrying extra shifts; yes, this rotation has been under-staffed.”

7. Dealing With The System: Chiefs, PDs, and Politics

Not all leadership is created equal. Some chiefs really get it. Some PDs absolutely don’t.

You need a strategy for less-than-ideal systems.

7.1. Talking to chiefs

Chiefs are usually your safest first step. They’re close enough to understand, high enough to move some levers.

How you frame it matters:

Don’t say:

- “X is incompetent” or “X is a mess.”

Do say:

- “I’m worried about X. There’s been a noticeable change from their baseline—more errors, more fatigue, and I’m concerned about their well-being and patient safety.”

Be specific:

- “They’ve stayed 3–4 hours late most days this week picking up dropped tasks.”

- “They’ve said things like ‘I don’t care if this patient dies’ that are very unlike them.”

- “They almost gave 10x the insulin dose yesterday and caught it at the last second.”

You are not diagnosing depression. You’re describing behaviors and impact.

7.2. When the chief shrugs it off

Sometimes you get: “Yeah, that rotation does that to people. We all went through it.”

Unacceptable answer.

You can push, firmly but professionally:

- “I hear you that it’s a hard rotation. I’m telling you this feels beyond the usual miserable. It looks unsafe—for them and for patients. I don’t feel comfortable ignoring it.”

If they still stonewall?

You go up a level: PD, associate PD, GME office, wellness committee. Preferably with another resident who has seen the same issues.

8. Protecting Yourself While You Step Up

You can’t pour from an empty tank. You also can’t help anyone if you burn yourself out trying to buffer the system for two people.

Set a few non-negotiables:

You will not permanently become “the person who does all their work.”

Short-term help is fine. Long-term shift-dumping is not.You will not hide dangerous errors to “protect” them.

That hurts patients and eventually hurts them more when something serious happens.You will not keep escalating alone if leadership is ignoring you.

Bring in another co-resident. Document key events (for yourself, not as a legal record).You will still set boundaries:

- “I can cover your pages for 30 minutes but I have to pre-round after that.”

- “I’m here to support you, but I’m not trained to be your therapist. I think talking to [mental health/EMP/EAP] is the next step.”

9. Practical Tools: Scripts, Emails, and What to Actually Say

You will be tired, probably post-call, and not at your most articulate. So steal this language.

9.1. Script to the co-resident (mild concern)

“Hey, I’ve noticed you’ve seemed more drained and checked out the last couple weeks—staying late, quieter than usual. This rotation is awful, but I’m concerned about you specifically. How are you holding up? Anything I can take off your plate today?”

9.2. Script to the co-resident (serious concern)

“I’m worried about you. You’ve talked about not caring if you wake up, and I’ve seen you struggle with things that are usually easy for you. That makes me think this is beyond ‘tired.’ I care about you and about patient safety, so I think we need to loop in [Chief/PD]. I’m willing to be with you for that conversation.”

9.3. Email to chief (if you’re the one escalating)

Subject: Concern about co-resident on [Service]

“Hi [Chief],

I wanted to raise a concern about [Name], who is currently on [Service]. Over the past [time frame], I and others have noticed a significant change from their baseline—marked fatigue, emotional distress, and some near-misses clinically.

Examples:

- [Example 1: brief but concrete]

- [Example 2]

- [Example 3, if relevant]

I’m concerned about their well-being and the risk of errors given the current workload. I’ve checked in with them and encouraged them to reach out, but I think this may warrant leadership awareness and support.

Happy to discuss more by phone or in person.

Best,

[Your Name]”

9.4. If leadership asks you to “keep an eye on them”

Clarify expectations:

- “I can check in on them as a colleague, but I don’t feel comfortable being solely responsible for monitoring their safety. What supports can be put in place from the program side?”

Translate: I’ll help, but I’m not your unpaid risk-management staff.

10. If They Refuse Help: What You Still Can (and Must) Do

Some people will shut you down hard:

- “I’m fine, drop it.”

- “If you tell anyone, I’ll deny it.”

- “I can’t afford to look weak.”

You still have a responsibility. But your tactics change.

Keep the door open.

- “Okay, I won’t push you right now. But I’m not blind to how hard this is hitting you. If you change your mind or need anything, I’m here, no judgment.”

Keep your eyes on patient safety.

If they’re consistently unsafe—errors, missed labs, not seeing patients—you’re obligated to escalate even if they’re angry.

You can frame it to them:

- “I can’t un-see what I’ve seen clinically. I’m going to have to tell [Chief] about the safety stuff. I will frame it as concern and support, not you being ‘bad’.”

Pick your battles.

Not every crying spell needs a PD meeting. Not every snappy comment is a crisis. But:

- Repeated near-misses,

- Hopeless or suicidal talk,

- Inability to function on basic tasks

Those cross the line from “rough month” to “unsafe.”

11. The Quiet After: Following Up Without Hovering

You intervened. Chiefs got involved. Maybe they’re off service, reduced hours, or meeting with mental health. Now what?

Do not act like they’re made of glass. Do not completely avoid it either.

Something like:

- “Hey, I’m glad you got some backup. How are things feeling now compared to a couple weeks ago?”

- “If I overstepped when I raised the alarm, I’m okay with you being annoyed. But I’m not sorry I did it; I was scared for you.”

And then talk about normal life. Fantasy football. Coffee. The consult that made no sense. Being treated like a human, not a problem, is part of their recovery.

12. Zooming Out: Making Your Program Slightly Less Toxic

You’re not going to fix ACGME with a wellness poster. But on your team and within your class, you can shift norms.

A few small, real things that matter:

- Normalize saying “I’m at capacity today—can someone help with X?” without shame.

- In your group chats, reward honesty: “Thanks for saying that, I’ve been there too,” instead of “lol same” and moving on.

- As a senior, set expectations that asking for help is part of being safe, not weak.

- In resident meetings, bring up workload patterns that are breeding burnout, with specific examples.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Fear of stigma | 40 |

| Career impact | 30 |

| Time constraints | 15 |

| Lack of trust | 10 |

| Not recognizing severity | 5 |

You can’t solve burnout at the individual level alone. But you can stop pretending it’s purely a “resilience” problem. It’s mostly structural—and you’re allowed to say that out loud.

13. What You Should Remember Tonight On Call

Three things, if nothing else:

- If your gut says, “This is more than tired,” you’re probably right.

- You’re not betraying a friend by getting them help; you’re doing the job the system pretends to do.

- You’re allowed to set limits. You can care about them and still protect your own sanity.

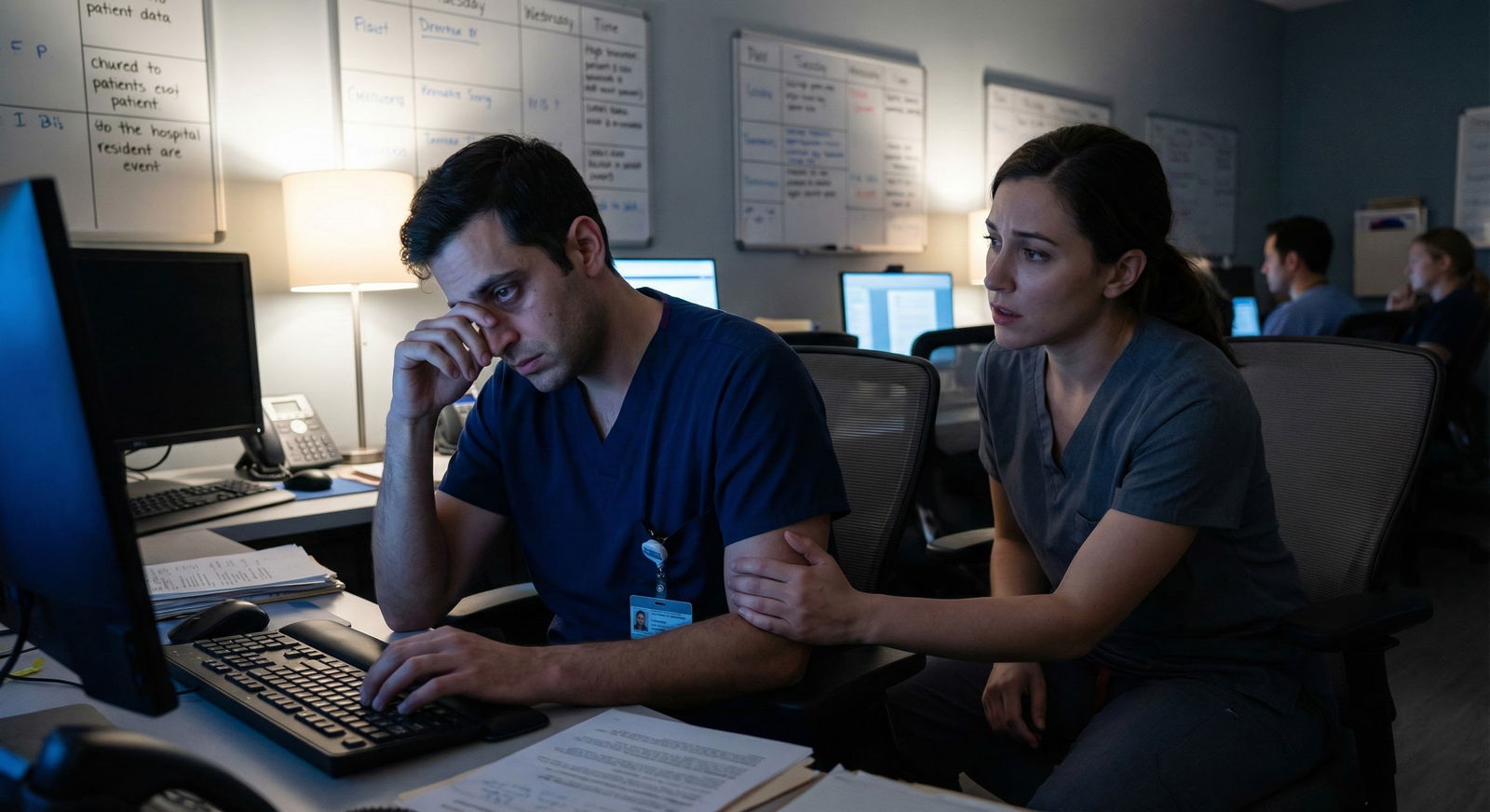

Next time you see that co-resident staring blankly at the screen at 3 a.m., you’ll know this isn’t just “their problem.” It’s yours too, in the sense that you’re on the same sinking ship—and that means you have a say.

You’re learning how to practice medicine. Part of that is learning how to practice with other human beings who break, crack, and sometimes recover. Being the person who intervenes skillfully when someone is burning out is not extra credit; it’s core clinical work.

With those skills in your pocket, you’re not just surviving residency. You’re starting to become the kind of colleague people trust when things get dark. And that matters—for the nights ahead, and for the teams you’ll eventually lead. But building those teams? That’s a problem for your attending years.