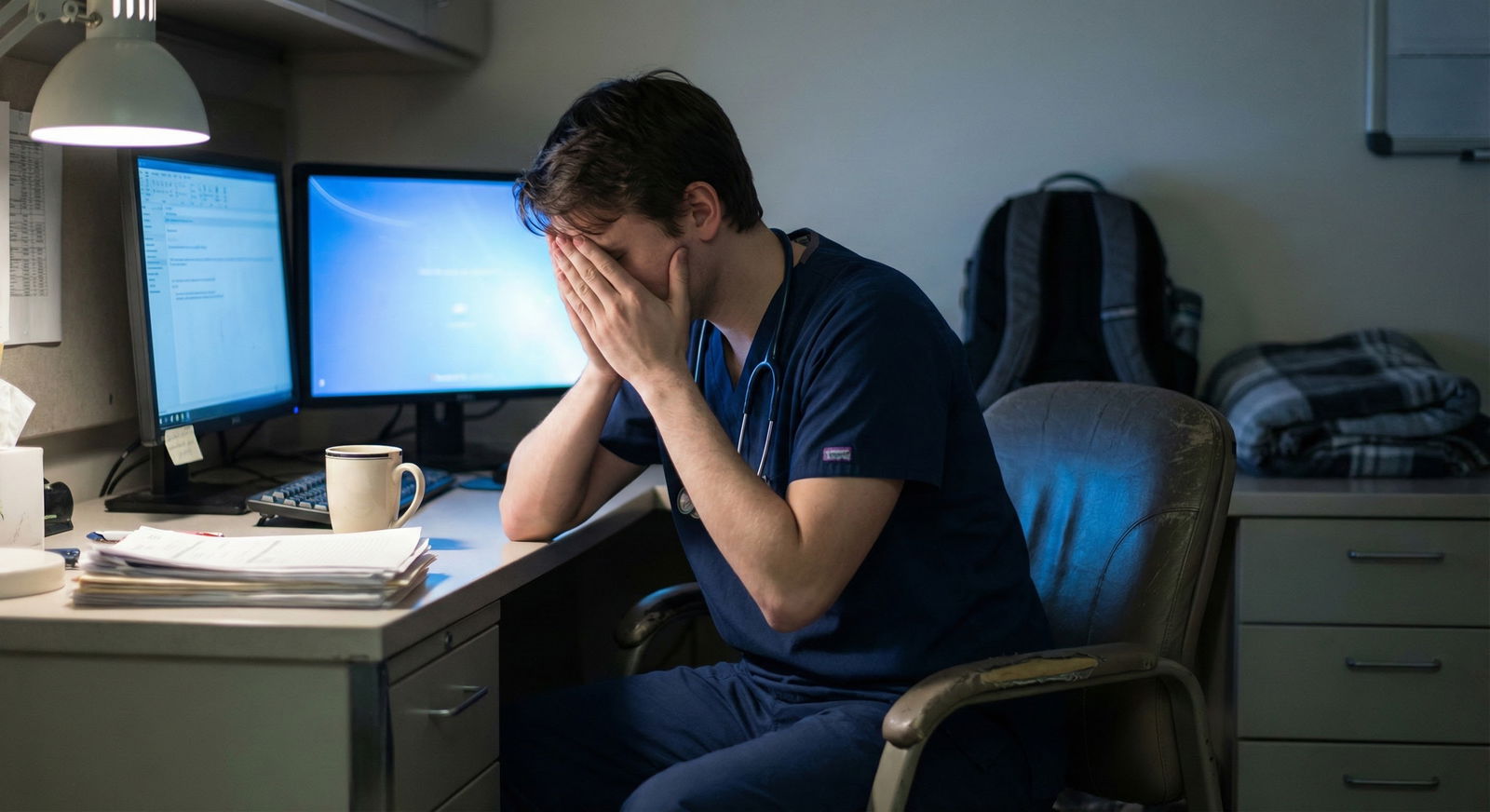

What do you actually do when you’re burned out and terrified that talking about it will tank your evaluations or even your career?

Here’s the answer: you don’t start with the PD. And you don’t blast an email to the GME office. You start safely and strategically.

Let me walk you through exactly how.

The Short Version: Who First, Who Second, Who Last

If you just want the quick hierarchy, here it is:

First line (lowest risk, highest psychological safety):

- Trusted co-resident or friend

- Chief resident (usually)

- Confidential wellness/mental health services (hospital or outside)

Second line (when you need schedule changes, accommodations, or formal help):

- Program leadership delegate (APD, site director)

- Program director (PD), once you’re clear on what you need

Third line (formal, structural, or safety-level stuff):

- GME office

- HR / Occupational Health

- Physician Health Program (state-level), in some cases

Burnout is common. Career damage from handling it badly is optional.

Let’s sort out where you should start.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Co-resident/friend | 35 |

| Chief resident | 25 |

| Program director | 15 |

| GME/wellness office | 10 |

| Outside therapist | 15 |

Step 1: Figure Out What You Actually Need

Before choosing who to talk to, you need one thing clear:

Are you asking for:

- Emotional support?

- Practical changes (schedule, time off, leave)?

- Protection (from a toxic attending, unsafe workload, harassment)?

- Formal documentation (for leave, accommodations, illness)?

Each category points to a different “first call.”

If you mostly need emotional support

You’re exhausted, cynical, not sleeping, crying in the bathroom between admissions, but you’re not in immediate danger and can still show up.

Start with:

- A trusted co-resident

- Chief resident

- Therapist or counselor (ideally confidential and outside your eval chain)

Why? Because your first conversation should be low stakes. You don’t want your “trial run” of articulating what’s wrong happening in front of the person who signs off on your contract renewal.

If you need something to change in the program

You’re thinking:

- “I can’t keep doing 28-hour calls every 3 days.”

- “I need a week off or I’m going to snap.”

- “This rotation is unsafe—too many patients, no supervision.”

Now you’re in “systems + schedule” territory. That usually requires involving:

- Chiefs (for schedule level fixes)

- APD/PD (for formal or sustained changes)

If you’re dealing with harassment, discrimination, or real safety issues

This jumps levels. If someone is:

- Abusing you

- Retaliating

- Impairing patient care

- Violating duty hours blatantly and repeatedly

Then you’re not just “burned out”—you’re in safety and compliance land. That’s where:

- GME

- HR

- Institutional reporting lines

may need to get involved, sometimes early.

You don’t have to figure this out alone—this is where a chief or a trusted faculty advisor can help you triage whom to bring in.

Chiefs vs PD vs GME: What Each Can Actually Do

Think of it this way: everyone has a lane. Use the right lane for the right problem.

| Issue / Need | Best First Contact |

|---|---|

| Emotional support, validation | Co-resident or chief |

| Schedule tweaks, lighter month | Chief resident |

| Medical leave / formal time off | PD or APD |

| Rotation/site change for fit | APD or PD |

| Toxic attending, bullying, retaliation | Chief or GME (case-dependent) |

| Systemic duty hour violations | Chief → PD or GME |

Chief Resident: Often Your Best First “Official” Stop

For burnout, chiefs are usually the safest bridge between “I’m struggling” and “I need changes.”

What chiefs can often do:

- Quietly lighten your schedule for a bit (swap calls, adjust rotations)

- Put you on a lower-intensity elective after a brutal block

- Run interference with a difficult attending (“I’ll talk to them”)

- Help you script a conversation with your PD

- Tell you, candidly, what’s been done before for similar situations

What they usually can’t do alone:

- Approve extended medical leave

- Permanently change your training timeline

- Overrule the PD long term

When starting with chiefs makes sense:

- You’re worried about being “judged” by PD but you need some kind of help

- You’re not sure if your situation is “bad enough” to escalate

- Your main issue is workload, schedule, or rotation environment

I’ve seen chiefs quietly move a resident from nights to a cushier consult month after hearing “I’m not OK.” No drama. No formal label. Just support.

That said, if your chief is part of the problem (condescending, dismissive, gossip-prone), skip them. Trust your read.

Program Director: When (and How) to Bring Them In

PDs have power you actually need for the bigger stuff:

- Official leave of absence

- Modification of training plan

- Changing away from a toxic site

- Formal documentation that protects you (e.g., “resident took leave for health reasons,” not “resident disappeared and underperformed”)

But they’re also:

- Evaluating you

- Writing your final letter

- Deciding on promotion or remediation

So don’t just barge in unprepared.

When you should talk to your PD early

- You’re not safe from yourself (suicidal thoughts, self-harm risk)

- You need significant time off (weeks to months, not a single mental health day)

- Your performance is already slipping and being noticed

- You’re thinking about switching specialties or leaving medicine

In those situations, not looping in the PD is actually more dangerous long-term. If your charted history looks like “poor performance and unreliability,” and there’s no context, that will follow you.

How to frame the conversation with your PD

Go in with:

- A clear, honest but controlled description:

- “I’ve been experiencing significant burnout—sleep problems, emotional exhaustion, and it’s starting to affect how I feel on the wards.”

- A safety statement:

- “I’m still committed to patient safety. I’m here because I want to make sure I stay safe for patients and myself.”

- A concrete ask:

- “I’d like to talk about a brief leave and a gradual return plan.”

- “I’m wondering if we can adjust the next few months’ rotations while I work with a therapist.”

Avoid vague, open-ended dumping like “Everything is awful and I hate medicine,” even if that’s how you feel. You’re allowed to feel that way—but your PD needs something actionable.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Feeling burned out |

| Step 2 | Emergency care / crisis line |

| Step 3 | Inform PD when safe |

| Step 4 | Talk to trusted peer or chief |

| Step 5 | Use support, therapy, small schedule tweaks |

| Step 6 | Meet with PD or APD |

| Step 7 | Involve GME office |

| Step 8 | Implement plan with PD/chief |

| Step 9 | Immediate danger? |

| Step 10 | Need formal change? |

| Step 11 | Systemic or safety issues? |

GME Office: Powerful but Blunt Instrument

GME is not your therapist. It’s your structural backup.

They oversee:

- Duty hour compliance

- Resident safety and work environment

- Leaves, accommodations, policy-level stuff

- Situations where the program is the problem

When going to GME first might be appropriate:

- You’ve already tried raising concerns internally and got retaliated against

- Your PD is the problem (bullying, discrimination, retaliatory behavior)

- Duty hour or safety violations are obvious, ongoing, and ignored

- There’s abuse or harassment you don’t trust the program to handle fairly

But here’s the catch: once GME is involved, it’s “on the record.” That’s not necessarily bad, but it’s formal. There may be documentation, investigations, emails. You want to be sure that’s the level you need.

A safer pattern:

- Talk to a chief or trusted faculty mentor: “Is this something that should go to GME?”

- If yes, go in with specific examples, not just “I’m burned out.”

- “We routinely work 100-hour weeks on this rotation.”

- “We’ve reported this attending’s behavior; nothing changed.”

For pure burnout without structural abuse? GME is usually a second- or third-line resource, not your starting point.

Confidential Mental Health: Honestly, This Should Be Parallel to Everything

You don’t need anyone’s permission to see a therapist.

Use:

- Hospital-sponsored confidential counseling (if it’s truly firewalled from evaluation)

- Independent therapist/psychiatrist outside your hospital system

- A physician health program if you’re worried about impairment or substance use

Most residents I’ve seen climb out of burnout did both:

- An internal support route (chief/PD) for practical changes

- An external route (therapist) for actual healing and coping

If you’re afraid of PD/GME seeing your records, choose someone completely outside the system. Pay cash if you have to. Your mental health is worth more than $150 a session.

What About Documentation, Licensing, and Careers?

The fear is real: “If I admit I’m burned out or depressed, will this haunt me forever?”

A few blunt points:

- Licensing boards are (slowly) moving away from punishing people for getting help. Many now focus on impairment, not diagnosis.

- Silent suffering that leads to major errors, sudden leave, or dropping out looks worse than a documented period of illness and recovery.

- You can say “health reasons” in a generic way on future forms and still be truthful.

PDs are often more sympathetic than residents expect when you come early, before everything blows up. I’ve seen PDs:

- Build modified schedules

- Approve 4–8-week leaves

- Write letters affirming a resident successfully completed training after recovery

What scares PDs is the resident who implodes without warning.

Concrete Playbooks: What To Do in Common Scenarios

Let’s make it ultra-practical.

Scenario 1: “I’m exhausted, bitter, and numb but still functioning.”

- Talk to a trusted co-resident that you actually trust.

- Then talk to your chief:

“I’m getting pretty burned out. I’m OK clinically, but I’m running on fumes. Is there any way we can ease up my next month or find some breathing room?” - In parallel, book therapy. Don’t wait.

No need to run to PD/GME yet unless things worsen.

Scenario 2: “I’m crying before every shift and I’m starting to slip.”

- Tell a chief or trusted faculty ASAP.

“I’m not doing well and I’m worried it’s starting to affect my work.” - Schedule an urgent appointment with a therapist/PCP/psychiatrist.

- Depending on severity, set up a meeting with your PD or APD: “I’ve been struggling with burnout/depression and I’m working with a therapist. I want to stay safe for patients and myself. Can we discuss a short leave or reduced load while I get stabilized?”

This is where PD involvement is appropriate and protective.

Scenario 3: “The rotation itself is abusive. Everyone is drowning.”

- First, sanity-check with co-residents: “Is it just me, or is this unsafe?”

- Bring specifics to the chief: “On average we’re working 100 hours, no days off in 14, and we’re covering 30+ patients alone at night.”

- If chiefs and PD blow it off or retaliate, then consider:

- GME office

- Duty hour reporting systems

- Anonymous channels if available

Now you’re not just talking burnout. You’re talking system failure.

Scenario 4: “I’m having suicidal thoughts.”

This bypasses hierarchy.

- Seek immediate help:

- Crisis line / ER

- On-call psychiatry

- Trusted friend to stay with you

- Once you’re safe, loop in PD/leadership with support from:

- Your treating psychiatrist

- A therapist

- A chief who can sit with you in the meeting

Your career is not more important than your life. Period.

FAQs

1. Will my PD think I’m weak if I bring up burnout?

If your PD is worth anything, no. Most have seen multiple residents hit burnout. Many have been there themselves. What they do judge—quietly—is residents who wait until there’s a serious error or crash before saying anything. Coming early is actually a sign of responsibility.

2. Should I email or ask for an in-person meeting?

For first conversations about real burnout, request an in-person or video meeting. The email should be simple:

“Hi Dr. X, I’ve been going through some personal/health challenges and would appreciate a brief meeting to discuss how I can stay safe and effective at work.”

Don’t dump your whole story in writing. Save it for the conversation.

3. What if I don’t trust my chief or PD at all?

Then widen your circle:

- A different chief (from another class or site)

- A faculty mentor or advisor outside your direct chain

- GME wellness office or ombuds (if truly confidential)

- External therapist first, then decide who internally to involve

You don’t have to start with the person who scares you most.

4. Can talking to GME come back to bite me later?

It can create a paper trail, yes. That’s not automatically bad. If your main issues are serious structural problems or retaliation, having GME involved is protective. If your issues are more personal burnout, therapy + chiefs + PD is usually the cleaner first route. Use GME when program-level issues are the problem, not when you just need support and a breather.

5. How do I talk about this on future applications or credentialing forms?

You don’t need to give a dramatic confession. You can say:

- “I took a brief, approved leave for health reasons during residency and returned in good standing.”

If directly asked about impairment, answer honestly but briefly: - “I experienced a period of burnout/depression, got treatment, and have been stable and fully functional since [year].”

Owning it calmly is far better than pretending nothing happened and having unexplained gaps or bad evaluations.

Key takeaways:

- Start where it’s safest: co-resident, chief, therapist. Don’t open with GME unless it’s a structural or safety crisis.

- Bring in your PD when you need formal changes—leave, modified training, serious support—not just a vent session.

- Use GME when the system is the problem or internal leadership has failed you, not as your first casual burnout consult.