You will be asked to cover a specialty you barely know. Overnight. And no, it’s not optional.

If you stay in residency long enough, you will eventually get this page or email:

“Hey, schedule change. You’re covering [specialty you don’t know] tonight.”

Could be neurosurgery when you’re an IM resident. Could be pediatrics call when you’re categorical in surgery. Could be OB triage when you’ve done exactly two L&D shifts and mostly held retractors.

The situation feels unsafe. Sometimes it actually is. But you can survive it and protect patients if you’re systematic and a little ruthless about your limits.

This is not about being a hero. It’s about not hurting people and not getting yourself crushed.

Let’s walk through exactly what to do from the moment you find out you’re covering “the random service” until you sign out in the morning.

Step 1: Before the Shift – Stabilize the Situation, Not Your Ego

You find out you’re covering a specialty you barely know. The clock’s ticking.

1. Clarify the assignment now, in writing

Do not just “roll with it.” You need specifics.

Email or message the chief or scheduler something like:

“Confirming for tonight: I am covering [service] from [time–time]. I’m a [PGY level, primary specialty] with limited experience in [this field]. Please confirm:

– Who is backup (name, role, phone/pager)?

– What issues should I not manage independently?

– Where are service-specific protocols kept?”

You want this documented. If later someone asks why you were managing status epilepticus alone as a psych resident, you’ll be glad this exists.

If they dodge the backup question, push once more, clearly:

“To keep patients safe, I need a designated in-house or home-call backup for specialty-specific issues. Who should I call first for urgent questions?”

If the answer is “there isn’t one,” you escalate to the attending or program leadership. Politely, but directly:

“I am concerned about patient safety if I’m the sole coverage for [neuro ICU / OB triage / etc] without specialty backup available.”

You’re not being dramatic. You’re being responsible.

2. Identify your three most likely disasters

Every specialty has 3–5 “you absolutely cannot screw this up” emergencies.

Ask the chief/attending or a friendly upper level:

“What are the top 3 emergencies I’m likely to see tonight where time matters?”

Examples:

- OB: Category III fetal heart tracing, shoulder dystocia, postpartum hemorrhage

- Neuro: New focal neuro deficit, seizure/status, acute mental status change

- Cards: Chest pain, arrhythmia, decompensated heart failure

- Peds: Respiratory distress, dehydration/shock, fever in neonate

- Surgery: Acute abdomen, post-op hypotension/tachycardia, compartment syndrome

Write them on a sticky note or your phone with “Trigger = Call senior/attending now.”

3. Build a 30-minute crash plan

You do not need to “learn the specialty” in an afternoon. That’s impossible.

You need:

- How to not miss emergencies

- Where to find orders/protocols

- Who to call when you’re lost

Do a focused 30-minute prep:

Text/email a resident on that service:

“I’m cross-covering your service tonight. Can you send me:

– Standard admission order set you use

– Common overnight issues and your usual go-to orders

– Any ‘always call the attending’ situations?”-

- Find that service’s usual admission/consult order sets

- Bookmark key order sets: sepsis, chest pain, transfusion, asthma, DKA, etc.

- Look at 1–2 recent notes from that service to see how they structure assessment/plan

Pick one trusted reference app/site:

- For meds/dosing: Lexicomp, Micromedex, Epocrates

- For approach: UpToDate, hospital handbook (like “UCSF Hospitalist Handbook” or your institution’s version)

You are building a workflow, not expertise.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clarifying role/backup | 5 |

| Emergency pattern review | 10 |

| Order sets & notes review | 10 |

| Reference/app setup | 5 |

Step 2: At Sign-Out – Extract the Information That Actually Matters

Sign-out is where most cross-cover disasters are born. Because people rush, assume knowledge, and mumble “he’s fine, just needs labs in the morning.”

You’re not in your usual terrain. You cannot afford vague.

1. Force structured sign-out

Use a simple mental template: “SICK / TRICKY / BORING.”

Ask the outgoing resident:

- “Who are your sickest two patients and what am I watching for?”

- “Which patients are most likely to cause trouble tonight?”

- “Who is stable and basically just needs vitals and not much else?”

Push for clear if/then:

- “If baby’s O2 sat drops below X, what should I do before I call you/attending?”

- “If this neuro patient gets more somnolent, what’s step one? CT? Labs? Call you?”

- “If this post-op patient’s systolic drops below 90, what’s your first move?”

You’re looking for specific triggers, not vague “let me know if they get worse.”

2. Get the “obvious to them, not obvious to you” details

You’re an outsider. They forget that. Ask:

“What’s normal here that would freak me out on my home service?”

(Example: neurosurgery tolerating high BPs you’d panic about in medicine, or vice versa.)“What would you never do on this service that’s common on mine?”

(Example: giving too much fluid to a neurosurgery patient with concern for ICP.)“Any no-go meds or fluids for these patients?”

(Example: bolusing large volumes in certain cardiac or renal patients.)

Jot short phrases only. You will not remember complex explanations at 3 am.

3. Clarify how much autonomy you actually have

Ask directly:

“Realistically, what do you expect me to manage alone, and when do you want a call?”

If you’re a PGY-1 thrown into something like neurosurgery nights, you should not be making solo calls about anticoagulation in a patient with a fresh subdural.

If their answer sounds like “just use your judgment,” say:

“I don’t have judgment in this field yet. Can we define 4–5 situations where I always call, even if I’m not sure it’s a big deal?”

You’re forcing them to think about safety. Good seniors will respect that.

Step 3: Overnight Strategy – Default to “Stabilize, Then Call”

The main rule: You are not there to be clever. You are there to keep people alive long enough for the real experts to direct care.

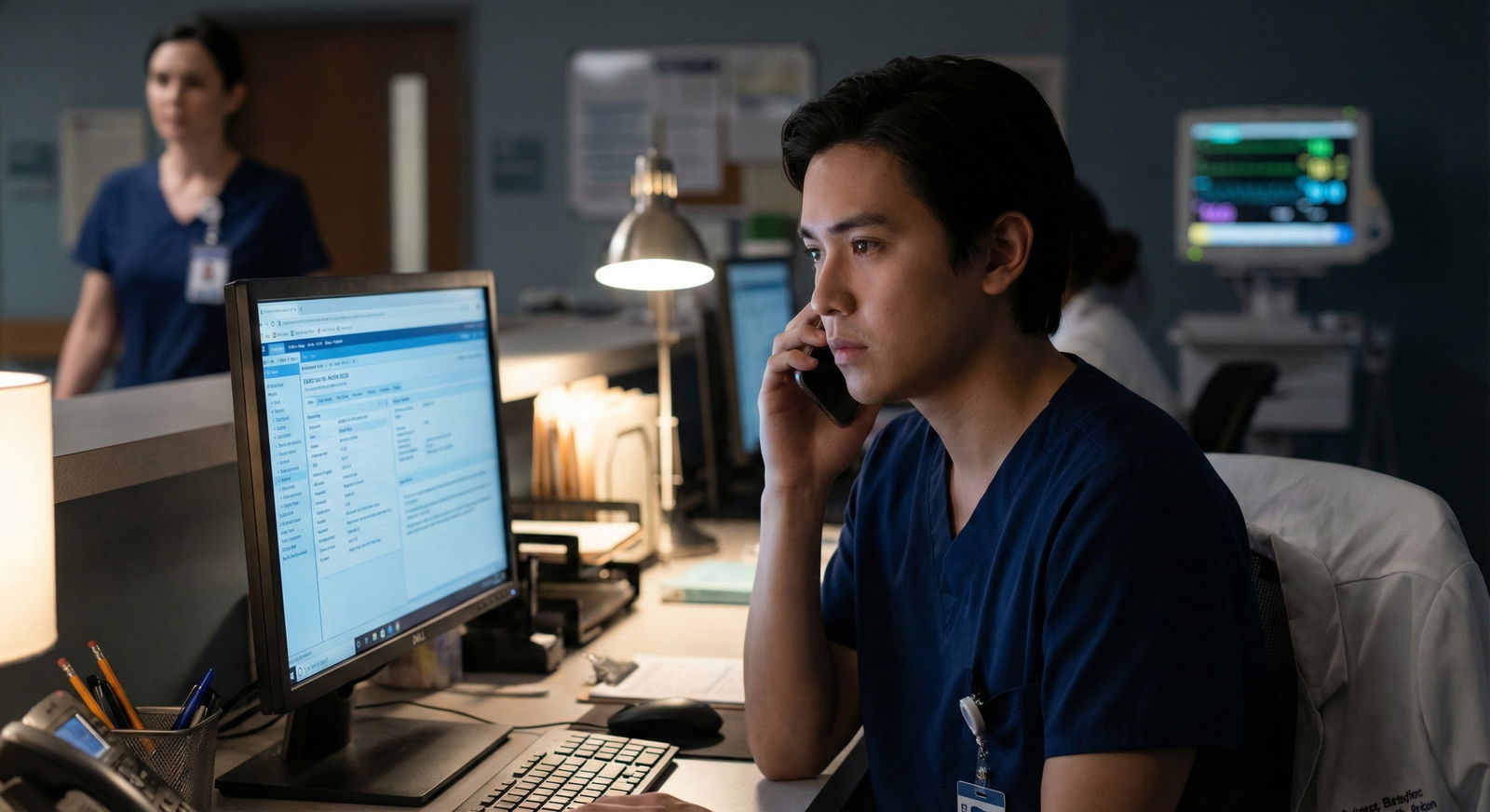

1. For every page: use a rigid first-step script

You’re tired. You’re out of your element. So you standardize.

When you get paged:

Ask the nurse three things:

- “What’s the main concern right now?”

- “What are the latest vitals?”

- “Have they changed significantly from baseline?”

Decide immediately:

- “Do I need to see them right now?”

- “Can I give a quick verbal and see in 10–15 minutes?”

- “Is this a simple order question I can safely handle by phone?”

If it’s breathing, mental status, chest pain, severe pain, bleeding, or weird neuro stuff → you see the patient. Physically. Now.

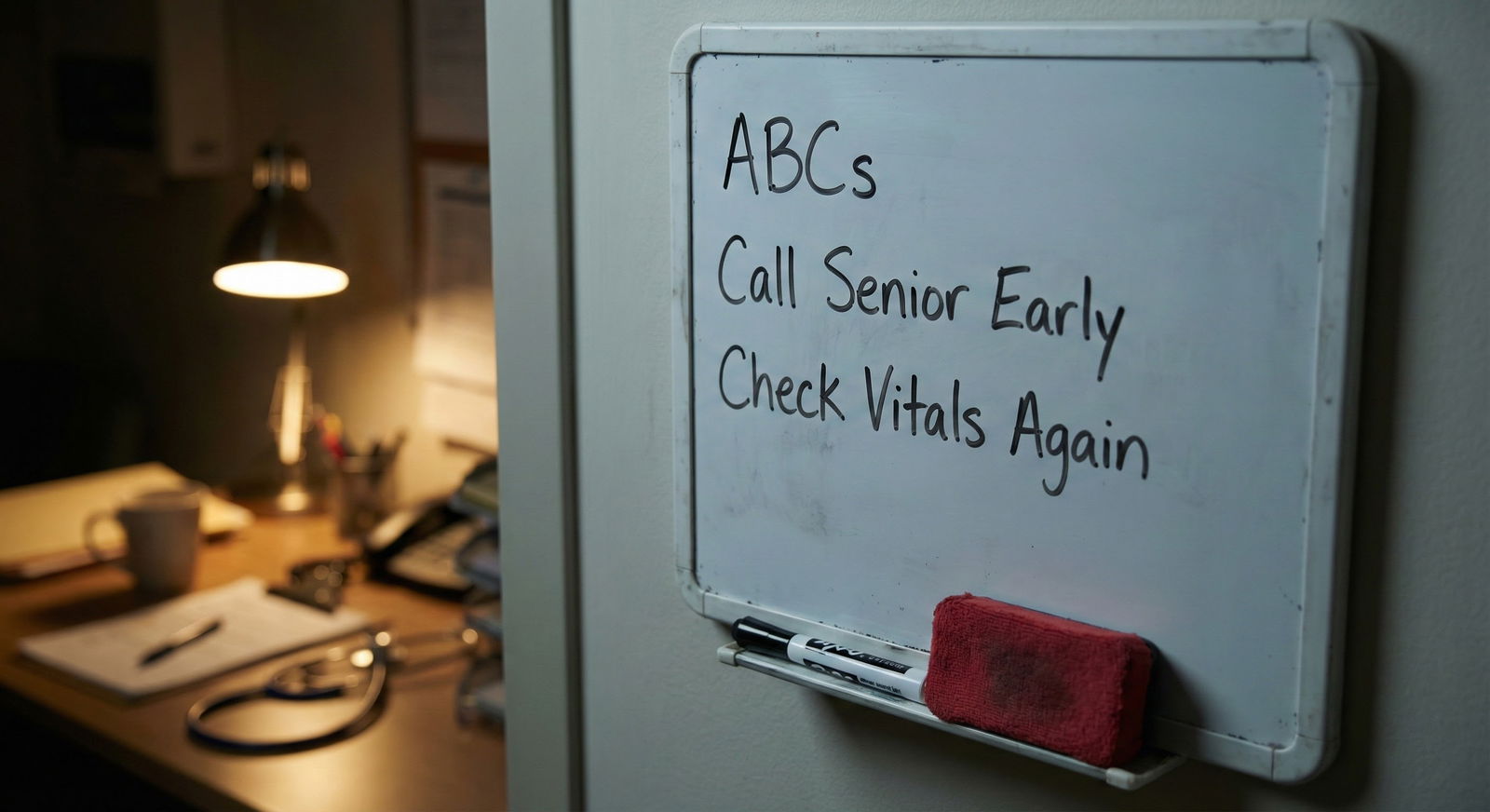

2. Run the basic ABCs on literally everyone you are unsure about

I don’t care if you’re covering ophthalmology. You’re still a doctor.

At bedside, run the unsexy checklist:

- Airway: talking? gurgling? choking?

- Breathing: RR, work of breathing, O2 sat, breath sounds

- Circulation: BP, HR, perfusion, cap refill, obvious bleeding

- Disability: orientation, pupils (basic neuro check), gross focal deficits

- Exposure: look at surgical sites, drains, rashes, lines

If ABCs are off, your job is:

- Stabilize using the most basic steps you know (O2, fluids, positioning, pain control, quick labs)

- Get help. Early.

You will never get in trouble for calling early on a decompensating patient. You will absolutely get in trouble for waiting “to gather more info” while they spiral.

3. Use “stabilize then consult” for specialty-specific problems

Let’s say you’re an IM resident covering OB and get a call: “Pregnant patient with severe headache and high BP.”

You may not fully remember the nuances of preeclampsia vs severe features vs HELLP. But you do know:

- High BP + pregnancy + headache = potentially bad

- ABCs, vitals, quick neuro exam

- Draw labs you know they’ll want (CBC, CMP, coags, type & screen, urine protein if relevant, etc.)

- Start basic stabilization: position, IV access, pain control (within reason)

- Then call the OB senior/attending with a structured report

Same with neurosurg: patient more somnolent with a history of recent bleed?

Stabilize: ABCs, head of bed up, vitals, get STAT CT head ordered, avoid messing with anticoagulation until you talk to them. Then call.

You are the first responder, not the final decision-maker.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Page Received |

| Step 2 | Ask nurse for concern and vitals |

| Step 3 | Go to bedside now |

| Step 4 | Phone order or delayed eval |

| Step 5 | ABCDs and focused exam |

| Step 6 | Stabilize with basics |

| Step 7 | Call senior or attending |

| Step 8 | Manage with standard orders |

| Step 9 | Reassess in set time |

| Step 10 | Emergent issue? |

| Step 11 | Unstable or new red flag? |

Step 4: Communication – Over-Call, Over-Document

When you’re out of your depth, communication is what protects you.

1. Call like a professional, not a terrified intern

When you call the senior/attending, do not ramble about your feelings. Give them data.

Use a crisp pattern:

- “I’m covering [service]. I’m calling about [patient, room, age, key diagnosis].”

- “Main concern: [one-line problem].”

- “Currently: [vitals, exam highlights, key labs/imaging if known].”

- “Actions I’ve taken so far: [brief list].”

- “My question: [what you want from them].”

Example:

“Hi Dr. Lee, I’m the IM resident cross-covering neurosurgery tonight. I’m calling about Mr. Smith in 8B, 65-year-old with subdural post-evacuation.

Main concern is increased somnolence over the last hour.

Vitals: BP 150/80, HR 88, RR 18, sat 96% on 2L. He’s now opening eyes to voice but not fully oriented, pupils equal and reactive, moving all extremities but slower than documented earlier.

I’ve elevated the head of the bed, checked glucose (110), and ordered a STAT CT head but it’s not done yet.

I’m not comfortable deciding if anything else is needed before the scan. How would you like to proceed?”

You sound competent, even if you feel clueless.

2. Document like someone will read it on Monday

Keep notes short but clear. When you’re on foreign turf, your notes matter more.

For any significant overnight event, include:

- What you were called for

- Objectively what you saw/found

- What you did

- Who you discussed it with and when

- Plan and follow-up steps

Example snippet:

“Called by RN re: increased lethargy in 65M s/p SDH evacuation. On exam: oriented to person only, following simple commands, no new focal deficits, pupils equal/reactive. Vitals stable. Checked fingerstick glucose 110. HOB elevated, maintained SBP <160. Ordered STAT CT head. Discussed case with neurosurgery attending Dr. Lee at 02:15; recommendation: await CT, call back immediately if worsening neuro status or SBP >160.”

This protects both you and the patient.

Step 5: Know the Hard Lines – When You Must Refuse or Escalate

There are times you should simply say no.

1. Procedures you are not trained for

If you have never done a C-section, you do not “just try” a crash C-section without appropriate surgical backup. If you’ve never done a central line and there’s no supervision, you don’t “practice” on the unstable ICU patient at 3 am.

Say:

“I’m not credentialed / trained to perform this procedure independently. We need someone who is, or we need to transfer/escalate.”

If someone pressures you, that’s their problem, not yours. Document the request and your response.

2. Orders with high risk and specialty nuance

Anticoagulation in neurosurg. TPA decisions. OB induction/augmentation. Chemo-related orders. Advanced cardiac device programming.

If your gut says “this is above my head,” it is.

Your script:

“This decision has high risk and is outside my training as [your specialty]. I’m not comfortable making this call without [specialty] involvement.”

Then call the appropriate attending or use your hospital’s chain of command.

3. Unsafe staffing or no backup

If you truly are the only one covering a high-risk unit with no backup (for example, one PGY-1 covering a busy L&D floor with no in-house OB), that’s not just “toughing it out.” That’s a systems failure.

For that night:

- Do your best, call early and often, keep documentation clean.

- After: bring it up with your PD or GME office. Calmly but firmly.

You’re not just advocating for yourself. You’re protecting future patients and residents.

| Situation Type | Your Minimum Response |

|---|---|

| Airway or severe resp distress | Go to bedside + call senior/attending |

| New neuro deficit or seizure | Bedside eval + STAT imaging + call |

| Hemodynamic instability | ABCs, fluids/pressors as trained + call |

| OB fetal distress/bleeding | Activate OB senior immediately |

| Any high-risk med/procedure | Refuse to act alone; get specialty input |

Step 6: After the Shift – Short Debrief, Real Learning

You survived. You’re exhausted. But there’s a way to turn that terrible night into actual growth.

1. Quick debrief with someone senior

Later that day or week:

- Grab your chief, attending, or a trusted senior.

- Pick 2–3 cases from that night you were most unsure about.

- Walk through what happened and what you did.

Ask bluntly:

- “Was there anything unsafe about how I handled this?”

- “Next time I’m cross-covering, what should I do differently?”

- “What should I have recognized earlier?”

This is how you convert anxiety into future competence.

2. Save a “cross-cover survival” file for yourself

Start a simple document or note on your phone: “Cross-Cover Pearls.”

After each weird overnight:

- Add a line or two:

- “OB – always ask about fetal heart tracing categories by name.”

- “Neuro – new somnolence = CT head before you try to explain it away.”

- “Cards – run EKG yourself if chest pain; don’t rely on ‘borderline’ note.”

Over years, this becomes your private handbook for being the person who can handle chaos on any service.

Mental Side: Managing the Fear Without Getting Reckless

You will feel like an impostor. Because you are, temporarily. The mistake is either 1) pretending you’re not, or 2) shutting down completely.

1. Accept you will not feel comfortable

You’re not trying to be comfortable. You’re trying to be:

- Systematic

- Honest about your limits

- Reliable in getting help

Tell yourself: “I don’t need to know everything. I need to not miss the big bad things and to call early.”

2. Watch your ego in both directions

Ego looks like two opposite behaviors:

- “I got this” — doing things far outside your training

- “I’m useless” — failing to use skills you actually have because it’s not “your” specialty

Reality: your core skills still apply anywhere:

- Recognizing sick vs not-sick

- Running basic resuscitation

- Communicating clearly

- Thinking systematically

Use them. That’s the value you bring, even on a foreign service.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Perfect diagnoses | 10 |

| Flawless specialty management | 15 |

| Early recognition of deterioration | 90 |

| Good communication | 80 |

| Knowing when to escalate | 95 |

3. Don’t catastrophize every page

Not every call is “someone is dying.” Many are:

- Pain meds

- Nausea

- Sleep

- Lab abnormalities you can manage with simple steps

Your rule: treat everything with respect, not panic. Use the same approach:

- Clarify

- Decide if bedside is needed

- Evaluate

- Act within your lane

- Escalate if out of your lane

That’s the job.

Fast Specialty-Specific Cheat Questions

If you only remember one thing per unfamiliar field, make it a question you always ask yourself:

- OB: “Is mom stable? Is baby stable?”

- Neuro: “Is this a new or worsening neuro deficit?”

- Cards: “Is this ischemia, arrhythmia, or pump failure?”

- Peds: “Is the airway safe and is this child perfusing?”

- Surgery: “Is this bleeding, infected, or obstructed?”

- Psych: “Is this medical? Is this safe for them and others?”

Those answers tell you how fast to move and who to call.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. What if the specialty attending is annoyed that I called “too early”?

Let them be annoyed. Your obligation is to the patient, not to their sleep. Keep your tone professional and your data organized. Over time, you’ll calibrate what truly needs a call, but on an unfamiliar service, your threshold should be low. Most reasonable attendings prefer an extra 4 am page to a missed stroke, bleed, or fetal distress.

2. How do I handle a nurse who expects me to know specialty-specific details I don’t?

Be transparent but not helpless. For example: “I’m cross-covering from internal medicine tonight and I don’t routinely manage [specific chemo regimen / fetal monitoring / device]. For now, here’s what I can safely do: [ABCs, vitals, labs]. I’m going to call the [service] senior/attending to clarify the plan.” Nurses respect clear ownership more than fake confidence.

3. Is it safer to just do nothing and defer everything until morning?

No. Doing nothing can be just as harmful as doing the wrong thing. Your job is to manage time-sensitive issues and prevent deterioration. That means: respond to pages, assess patients, fix obvious and safe problems (pain, fluids, oxygen, basic labs), and escalate early for anything you’re not qualified to handle. “Wait until morning” is only acceptable when you’re truly confident it’s routine or non-urgent.

4. What if my program routinely assigns unsafe cross-coverage with no backup?

Document patterns: dates, services, what backup was or wasn’t available, and any near-misses. Bring this to your chief, then your PD if needed. If you get brushed off and things are truly dangerous, escalate to the GME office. Keep the focus on patient safety and systems issues, not “I’m uncomfortable.” Use specific examples: “One PGY-1 covering 20 active labor patients alone overnight with no in-house OB.” That gets attention.

5. How can I prepare long-term for covering random services?

Treat every rotation as if you’ll someday cross-cover it alone. During that month: ask seniors for “night float survival tips,” save example admission orders, and jot down 5–10 “never miss” situations and their first steps. Build your personal cross-cover handbook over time. You’ll still feel uneasy when you’re thrown into a new field overnight—but you won’t be starting from zero.

Open your call schedule right now and find the next night you’re cross-covering outside your home specialty. Block 30 minutes the day before that shift to set up order sets, identify backup, and write your “3 emergencies I can’t miss” list for that service.