Most residents manage delirium wrong at 3 AM: they reach for haloperidol before they reach for the cause.

Let me walk you through how to do it correctly when you are exhausted, the nurse is frustrated, the patient is climbing out of bed, and there are four other pages waiting.

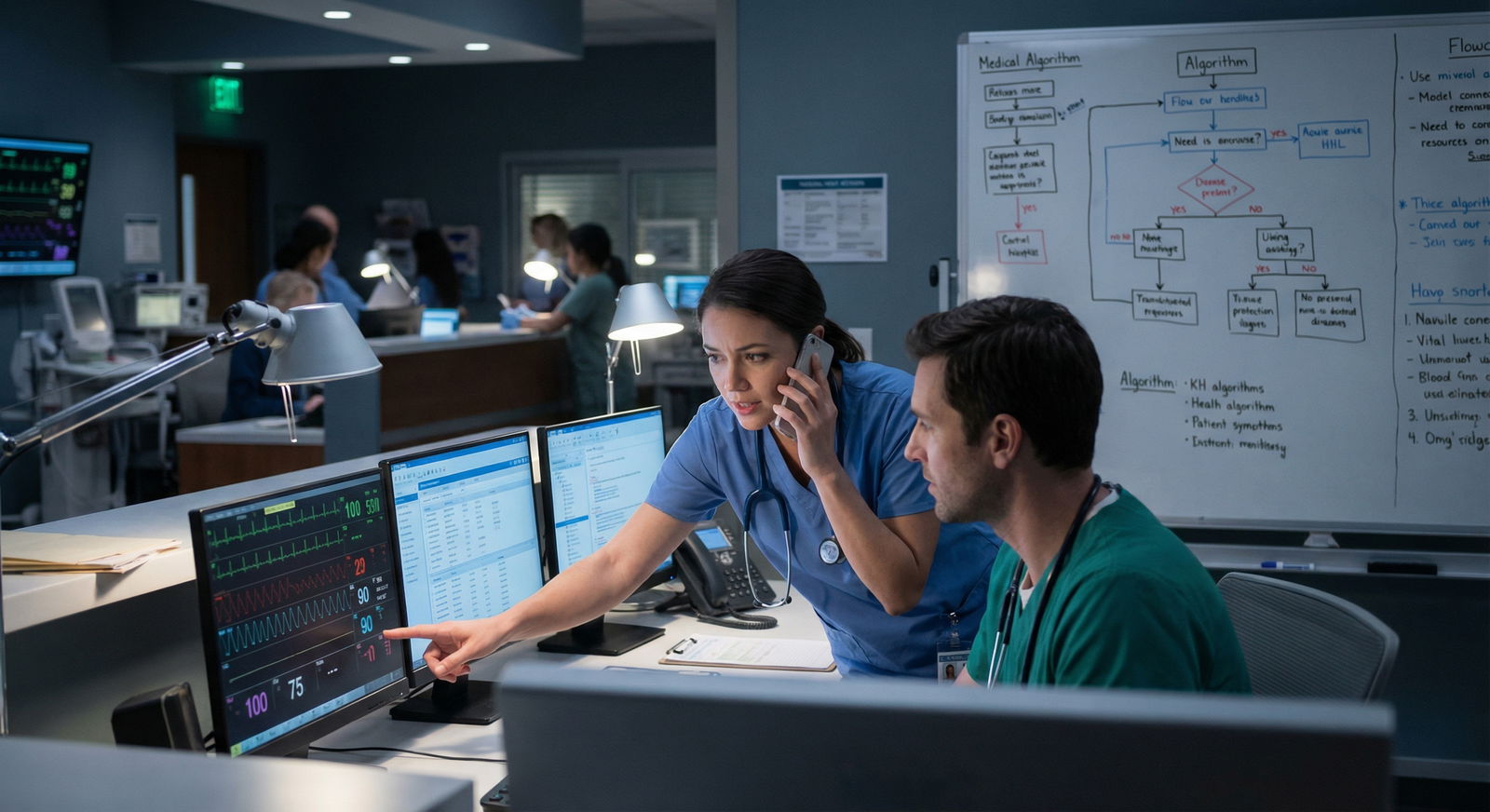

The 3 AM Reality Check

You are on call. Pager goes off: “Hey doc, your patient in 6B is trying to pull out his lines. He is yelling, confused, and almost fell. Can we get something for agitation?”

If your first thought is “Haldol 5 IM,” you are already behind.

At 3 AM, your job is not only to “make the patient quieter.” Your job is to:

- Rapidly rule out life‑threatening causes of delirium.

- Make the environment and team safer.

- Use the least medication necessary, in the safest way, with a plan to reassess.

You will not fix delirium in one night. You will prevent disasters, buy time, and keep the ship from sinking.

Step 1: Confirm It Is Delirium, Not Something Else

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Infection | 40 |

| Medications | 25 |

| Metabolic | 15 |

| Hypoxia | 10 |

| Withdrawal | 10 |

Delirium is an acute change in attention, awareness, and cognition that fluctuates. It is not just “old and confused.”

You need a 1–2 minute mental framework. Not a formal 30‑minute neuro exam.

Quick bedside triage

Ask the nurse three questions first (before walking in):

- “What was his baseline mentation yesterday / on admission?”

- “How long has this been going on? Hours? Days?”

- “Any recent meds or events? Opioids, benzos, new antibiotics, procedures, restraints, catheter, urinary retention, no bowel movement?”

Then at the bedside:

- Check ABC with your own eyes. Is he protecting his airway? Oxygen saturation? Work of breathing? If unstable, you are in resuscitation mode, not “delirium” mode.

- Look at vitals: fever, tachycardia, hypotension, hypoxia, hypertension (think withdrawal or pain).

Do a 30–60 second neuro screen:

- Level of alertness: hyperalert, lethargic, stuporous?

- Orientation: person, place, time, situation (do not obsess if he is off by one detail; you want change).

- Attention: ask him to name the months of the year backwards or just squeeze your hand every time you say the letter “A” when you read a series of letters. If he cannot maintain attention, that supports delirium.

- Speech: slurred, aphasic, mumbling?

- Focal deficits: new facial droop, slurred speech, unilateral weakness? If yes → stroke code, not “more haldol.”

Differentiate three things quickly

Delirium vs. dementia

Dementia is chronic, usually stable, clear until proven otherwise. Acute change over hours to days = delirium on top of dementia.Delirium vs. primary psychiatric

First episode psychosis at 75 with a UTI and creatinine 3.2? No. Assume delirium. Visual hallucinations, fluctuating consciousness, disorientation point toward delirium.Delirium vs. oversedation

Look hard at today’s med MAR: opioids, benzos, gabapentin, sleep meds, anticholinergics. If RN gave IV hydromorphone 1 mg 20 minutes ago to an 85‑year‑old 45‑kg woman, you are not dealing with “agitation” yet. You are watching the prelude to hypoventilation.

Step 2: Non‑Drug Tactics You Must Use Before (and With) Meds

This is where most residents underperform. They think non‑pharmacologic strategies are “day‑team stuff.” Wrong. Nights are when environment and routines are most toxic to a delirious brain.

Clear the obvious insults

Walk into the room and do a very fast scan:

- Foley catheter? Can it come out? Urinary retention or irritation drives delirium.

- Multiple IV pumps beeping? Get them quiet. The relentless beeping is like torture when delirious.

- Physical restraints? These escalate agitation. Make it a goal to remove them as soon as safely possible (after a plan is in place).

Then basic physiologic fixes:

- Pain: untreated pain is massive delirium fuel. Ask directly. If non‑verbal, look for grimacing, guarding, tachycardia. A low‑dose opioid, properly titrated, may calm more than an antipsychotic.

- Hypoxia: titrate oxygen, adjust cannula or mask, get respiratory therapist if needed.

- Hypoglycemia: fingerstick. Do not skip this.

- Constipation / urinary retention: check last bowel movement; bladder scan if unclear. A massively distended bladder will make any human insane.

Environment: low‑tech, high‑yield

At 3 AM, you cannot re‑design the hospital. But you can do three or four things immediately:

- Lighting: avoid full bright overhead lights, but do not leave the room in total darkness. Use a dim light so they can see you and the room. Extreme dark can worsen fear and hallucinations.

- Noise: shut off TV, reduce hallway chatter. Close the door partially if safe.

- Orientation cues:

- Say: “You are in the hospital. It is night time. I am Dr. X. You are safe.”

- Point to clock and calendar if visible. If not visible, at least tell them the time and date.

- Familiar objects: if family left glasses or hearing aids, put them on. A half‑deaf, half‑blind patient in a strange room at 3 AM is basically engineered to be delirious.

Behavioral tactics with the team

You need nursing on your side. The nurse has probably been struggling for an hour before paging you.

Things I tell the nurse clearly:

- “We are going to try to avoid heavy sedation if we can.”

- “Let us cluster care. Avoid waking him more than needed.”

- “If he is safe and just calling out, you can sit him up, reorient, offer water, and let him be. We are not treating ‘annoying’; we are treating dangerous.”

Try simple, non‑threatening maneuvers first:

- Sit at eye level. Do not stand over the bed shouting.

- Speak slowly, one instruction at a time.

- Use the patient’s name. “Mr. Johnson, I am here to help you. You are in the hospital because of pneumonia. Your daughter was here earlier.”

None of this is glamorous. But I have seen patients de‑escalate 30–50% of the time with environment + orientation + pain control alone, enough to avoid a big sedative hit.

Step 3: Hunt the Cause While You Stabilize

This is the part people skip at 3 AM. They sedate, leave, and plan to “figure it out in the morning.” That is how strokes, MIs, and sepsis get missed.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Agitated confused patient |

| Step 2 | Check ABC and vitals |

| Step 3 | Call rapid response |

| Step 4 | Focused bedside assessment |

| Step 5 | Review meds and MAR |

| Step 6 | Check glucose and labs |

| Step 7 | Look for infection source |

| Step 8 | Urine, lungs, lines, wounds |

| Step 9 | Consider stroke or seizure |

| Step 10 | Neuro exam and imaging if needed |

| Step 11 | Unstable |

Common causes you can and should check at night

You are not going to get a full geriatric delirium consult at 3 AM. But you can cover 80% of serious causes quickly.

Run this mental list:

- Hypoxia / hypercarbia → ABG/VBG if respiratory concern, adjust O2.

- Hypoglycemia / significant hyperglycemia → bedside glucose.

- Sepsis → new fever, leukocytosis, hypotension, tachycardia:

- Lungs (chest exam, recent CXR, sputum, oxygen needs).

- Urine (UA, culture if not done).

- Lines, surgical sites, skin.

- Metabolic: sodium way off, K high or low, calcium very low or very high, uremia, liver failure (ammonia is overrated but can be checked selectively).

- CNS:

- New focal deficit → CT or stroke code.

- Possible seizure / post‑ictal → history from nurse: stiffening, tongue bite, incontinence, eye deviation?

- Withdrawal:

- Alcohol: check CIWA history, last drink, sweating, tremor, hypertension, tachycardia.

- Benzos, opioids: look at outpatient med list and inpatient orders.

Do not order a “massive panel” without thought. But at minimum, for new unexplained delirium at night, I want:

- CBC.

- BMP (or CMP).

- Glucose (immediate).

- Maybe lactate if infection concern.

- Sometimes UA with culture, depending on story.

If something is obviously wrong (Na 118, glucose 35, SpO2 82% on 2L), that is your priority. An antipsychotic is cosmetic treatment until those are addressed.

Step 4: When and How to Use Medications (Without Hurting People)

Here is the core rule:

You use meds in delirium to protect the patient and staff from imminent harm and to allow essential care, not to make the patient “nice.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| IV Haloperidol | 1 |

| PO Risperidone | 3 |

| IV/IM Olanzapine | 2 |

| Dexmedetomidine | 0.5 |

(Values above are rough “hours to peak / clinically useful effect”, just to show haldol is not magic instant glue either.)

First: strong reasons to be very cautious with meds

Before you click “haloperidol 5 mg IV q4h PRN,” ask yourself:

Is this patient Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, or advanced parkinsonism?

If yes: typical antipsychotics (like haloperidol) can be devastating. They can cause near‑locked‑in rigidity and worse confusion.Is this QTc already prolonged (e.g., >500) or on multiple QT‑prolonging meds?

Then you need to either avoid or dose very cautiously and recheck EKGs.Is this alcohol withdrawal?

They need benzodiazepines (or phenobarb / dexmedetomidine guided by ICU), not haloperidol alone. Haldol might calm some behavior but does not prevent seizures or autonomic instability.

What actually justifies a sedating medication?

Legitimate indications:

- Actively pulling out central lines, endotracheal tube, chest tube, fresh vascular graft.

- Trying to climb out of bed with high fall risk, repeatedly, despite redirection and sitter/restraints.

- Physically aggressive, hitting staff or other patients.

- Cannot receive essential life‑saving care (e.g., pulling off BiPAP mask in acute pulmonary edema, fighting necessary oxygen delivery, refusing critical antibiotics after all attempts at explanation).

Gray zones:

- Yelling but not dangerous.

- Mild pulling at lines but redirectable.

- Insomnia without distress.

You do not need to sedate those automatically.

Step 5: Drug Choices and Specific Dosing Strategies

Now the part you probably wanted me to start with. But you needed the context first.

I will split this into typical antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and “ICU‑only options.”

1. Haloperidol (typical antipsychotic)

Workhorse at most hospitals. Overused, but useful when used correctly.

Good for:

- Hyperactive delirium with significant agitation.

- Patients without major QT prolongation, without Parkinsonism, not in alcohol withdrawal.

Avoid or minimize in:

- Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia.

- Markedly prolonged QTc or on several QT‑prolonging drugs.

- Severe hepatic failure (adjust doses).

Starting doses (frail vs robust):

- Frail elderly / small patient / lots of comorbidities:

- 0.5–1 mg PO/IV/IM once.

- Reassess in 30–60 minutes.

- More robust adult:

- 1–2 mg PO/IV/IM once.

- Rarely should you jump to 5 mg as first dose.

Maximum cumulative dose overnight should usually stay ≤ 10 mg total, often less. If you are repeating 5 mg IV every hour, something is wrong; call for backup.

Route:

- IV: fast onset, but more QT risk. Many places still use it commonly.

- IM: reasonable if no IV and patient refuses PO.

- PO: slower but safer if they will take it.

Monitoring:

- Baseline EKG if possible. At least know last QTc.

- Watch for dystonia, rigidity, akathisia; treat with benztropine or diphenhydramine if needed.

2. Atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone)

Evidence says they are not clearly superior to haloperidol for delirium, but they are often better tolerated in some populations.

Olanzapine

Nice option for severe agitation with less QT impact than haldol, and the IM form is handy.

Doses:

- 2.5–5 mg PO or IM once for elderly.

- Up to 10 mg in selected younger, medically stable adults.

- Avoid giving IM olanzapine within 1–2 hours of IV benzodiazepines due to respiratory risk.

Watch for:

- Sedation.

- Orthostatic hypotension.

- Extrapyramidal symptoms (less than haldol, but not zero).

Quetiapine

Better for patients with Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia when you truly need an antipsychotic. Also used when you want more sedation at night.

Doses:

- 12.5–25 mg PO once at night as a starting point in elderly.

- Reassess before giving more; it will sedate and can drop BP.

QT risk is there, but generally less concerning than haldol in moderate dosing.

Risperidone

Common on day teams, but less helpful for acute 3 AM crisis (slower onset, no IV/IM at most sites).

Doses:

- 0.25–0.5 mg PO in elderly.

- 0.5–1 mg PO in others.

Use mainly if you are planning for ongoing management, not for immediate violent agitation.

Step 6: Benzodiazepines – Friend and Enemy

Benzos cause delirium. Full stop. They worsen it in the majority of hospitalized elderly.

But they are essential when the cause of agitation is:

- Alcohol withdrawal (or other GABAergic withdrawal).

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal.

- Chronic high‑dose benzo user abruptly cut off.

In alcohol withdrawal:

- Use symptom‑triggered benzos (CIWA) if your hospital supports it and patient can be scored.

- IV lorazepam is common; diazepam or chlordiazepoxide also used depending on liver function and setting.

Example starting lorazepam doses:

- Mild–moderate withdrawal: 1–2 mg IV/PO, repeat based on scores.

- Severe: may require higher; often this is ICU territory.

You can add low‑dose haloperidol or atypical antipsychotic as adjunct for hallucinations or aggression, but they are not substitutes for GABA replacement.

Outside of withdrawal, I am very conservative:

- I almost never give a PRN IV lorazepam to an 82‑year‑old with new delirium at 3 AM “just to help them rest.” That is how you cause falls, aspiration, and next‑day ICU transfers.

Step 7: ICU‑Level Options (Dexmedetomidine, etc.)

If you are on a floor and need continuous sedation to keep someone from self‑extubating BiPAP or constantly ripping out lines, you should be asking: “Does this patient need ICU?”

| Setting | Typical Med Options |

|---|---|

| Floor | PO/IV/IM haloperidol, PO/IM olanzapine, PO quetiapine, PO/IV risperidone, symptom-triggered benzos for withdrawal |

| Stepdown | Higher frequency antipsychotic dosing, closer monitoring, sometimes precedex if protocol allows |

| ICU | Dexmedetomidine infusion, propofol, higher-dose benzos, continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring |

Dexmedetomidine (Precedex):

- Great for agitated patients on ventilator or NIV.

- Provides “cooperative sedation” with less respiratory depression.

- Requires continuous ICU‑level monitoring and titration.

If you are considering something like a dexmedetomidine infusion, that is not a floor call. That is a discussion with ICU.

Step 8: Restraints, Sitters, and Reality

Nobody likes restraints. But pretending they are never appropriate is nonsense. Your job is to use them legally, ethically, and minimally.

Sitters

If available, sitters are gold. A calm human presence can:

- Reorient frequently.

- Block unsafe movements.

- Press the call button before disaster.

Use a sitter when:

- Patient is repeatedly trying to get out of bed or pull out lines but is redirectable with 1:1 attention.

- You want to avoid heavier drugs in a frail patient.

Physical restraints

Last resort. Document the justification.

Acceptable justifications:

- Imminent threat to life or essential treatment (e.g., repeatedly pulling out ET tube, fresh vascular access, post‑op graft).

- Severely aggressive behavior endangering staff.

When you order restraints:

- Pair with a clear re‑evaluation time (e.g., reassess in 1–2 hours).

- Combine with non‑drug and drug measures aimed at getting them off as soon as possible.

- Involve nursing in a specific plan: “Let us try to get him calm tonight, and if he sleeps and wakes clearer, we can trial restraint removal in the morning with sitter.”

Step 9: Document and Hand Off so You Do Not Repeat the Same Night

What you write at 3:40 AM either saves you tomorrow night or curses the next resident.

Key elements in a short note:

- “Acute change in mental status since [time]; hyperactive delirium with agitation.”

- Current vitals; any concerning abnormalities.

- Brief focused exam, including neuro and attention.

- Likely contributors: infection, meds, metabolic, withdrawal, etc.

- Tests ordered overnight and any immediate results.

- Non‑pharmacologic measures implemented.

- Meds given: drug, dose, route, and response.

- Restraint use, justification, and plan to reassess.

- Clear to‑do for day team: “Please review for underlying causes of delirium, consider geriatrics/psych consult, adjust chronic meds, and develop long‑term delirium prevention plan.”

Hand‑off verbally in the morning if this patient was a major issue. “6B ripped out his IV tonight, needed 1 mg IV haldol x2, concern for UTI, UA pending, still very confused” should be in your sign‑out.

Putting It All Together: A Night‑Shift Algorithm

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Page for agitation |

| Step 2 | Assess ABC, vitals |

| Step 3 | Rapid response / ICU |

| Step 4 | Confirm delirium and check baseline |

| Step 5 | Non-drug measures and pain control |

| Step 6 | Focused search for causes |

| Step 7 | Monitor, labs, reorient, sitter |

| Step 8 | Consider antipsychotic or benzo if withdrawal |

| Step 9 | Evaluate contraindications |

| Step 10 | Give lowest effective dose |

| Step 11 | Reassess in 30-60 min |

| Step 12 | Repeat low dose or escalate level of care |

| Step 13 | Continue non-drug measures, plan for day team |

| Step 14 | Unstable |

| Step 15 | Danger to self or others? |

| Step 16 | Still unsafe? |

FAQ (Exactly 6)

1. Should I ever use haloperidol prophylactically to “prevent” delirium in high‑risk patients?

No. Prophylactic antipsychotics in un‑delirious patients have not shown consistent benefit and carry real risks (QT prolongation, extrapyramidal symptoms, oversedation). Focus on non‑drug prevention: sleep hygiene, pain control, early mobility, vision/hearing aids, minimizing lines and catheters, and avoiding deliriogenic drugs.

2. How fast should I recheck a patient after giving an antipsychotic at night?

For IV haloperidol or IM olanzapine: recheck within 30–60 minutes. You want to know if they had a therapeutic effect or if you overshot and over‑sedated. For PO agents, the onset is slower; still, someone (you or the nurse) should deliberately reassess behavior and vitals within 1–2 hours. Do not just “fire and forget.”

3. Can I use melatonin or trazodone to help sleep in delirious patients?

Melatonin is relatively safe and reasonable as part of a broader sleep strategy, though data are mixed. I will use low‑dose melatonin (e.g., 3 mg) at night. Trazodone at very low doses (25–50 mg) is sometimes used, but it can worsen confusion and cause orthostatic hypotension or oversedation, especially in the elderly. If the delirium is severe, I prioritize treating the underlying cause and using antipsychotics judiciously instead of tossing in more sedating agents.

4. What is the role of CT head at 3 AM in new delirium?

CT head is not mandatory for every delirious patient. You should order it urgently if there is any new focal neurologic deficit, recent head trauma, anticoagulation with concern for bleed, or unexplained decreased level of consciousness out of proportion to metabolic findings. For a known demented 88‑year‑old with UTI who is mildly more confused but nonfocal, you can often defer imaging to daytime discussion unless other red flags arise.

5. How do I manage delirium in a patient with known Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia?

Avoid haloperidol and other high‑potency typical antipsychotics if at all possible. They can dramatically worsen rigidity and mobility. Quetiapine (very low dose, such as 12.5–25 mg PO) or clozapine (rarely used acutely because of monitoring requirements) are preferred when antipsychotics are absolutely necessary. Non‑drug strategies and addressing underlying triggers are even more critical here. Involve neurology or geriatrics early if available.

6. When should I escalate to ICU for a delirious patient?

Escalate when the level of agitation requires continuous sedation that you cannot safely manage on the floor, or when vital signs and physiology are unstable: severe hypoxia requiring high‑flow or BiPAP that the patient is fighting, hemodynamic instability, severe alcohol withdrawal with refractory symptoms, or need for agents like dexmedetomidine or propofol. If you find yourself repeatedly giving escalating doses of sedatives or physically unable to keep the patient and staff safe, that is an ICU conversation, not “one more PRN.”

Key points, stripped down:

- At 3 AM, your priority is safety and cause‑finding, not “quiet.” Non‑drug measures plus targeted workup come before reflexive heavy sedation.

- Use the lowest effective doses of antipsychotics, avoid them in Parkinsonism and marked QT prolongation, and reserve benzodiazepines for true withdrawal states.

- Document clearly, hand off intentionally, and make delirium a shared daytime problem, not a nightly recurring crisis you keep treating with the same 5 mg of haldol.