What do you do when you’re in the middle of an RRT and two more get called overhead… with just you and a pager between all of them?

You will have that night. If you take call in any decent‑sized hospital, it’s not an if.

The first time it happens, most residents freeze for half a second. You’re at the bedside, suction in hand, nurse yelling that the pressure is 60, and then:

“Rapid response team to 7 West, room 732… Rapid response team to 8 East, room 815…”

Your brain goes blank. Then everyone looks at you.

This is where residents either quietly drown or quietly level up. The difference isn’t heroics. It’s having a mental script for exactly this chaos.

Here’s the playbook.

Step 1: In the first 10 seconds – call the shots out loud

You do not have time to philosophize. You have maybe 10 seconds to set the tone and divide the work.

Say it clearly, out loud, so everyone hears:

Identify who’s in front of you.

“I’m staying here. This is my sickest patient until proven otherwise.”Assign a runner / communicator.

“You—charge—call the operator and find out the reasons for the other two RRTs and who else is responding.”Declare a provisional plan for the other RRTs.

“Tell them: primary teams evaluate immediately, I’ll triage by phone in the next 2 minutes. If unstable—code blue, not RRT.”

You are not abandoning your current crashing patient to sprint blindly to the next one. That’s how you end up with three half‑managed disasters.

You stabilize the worst one first. Or at least figure out who that is.

Step 2: Get immediate intel on the other RRTs

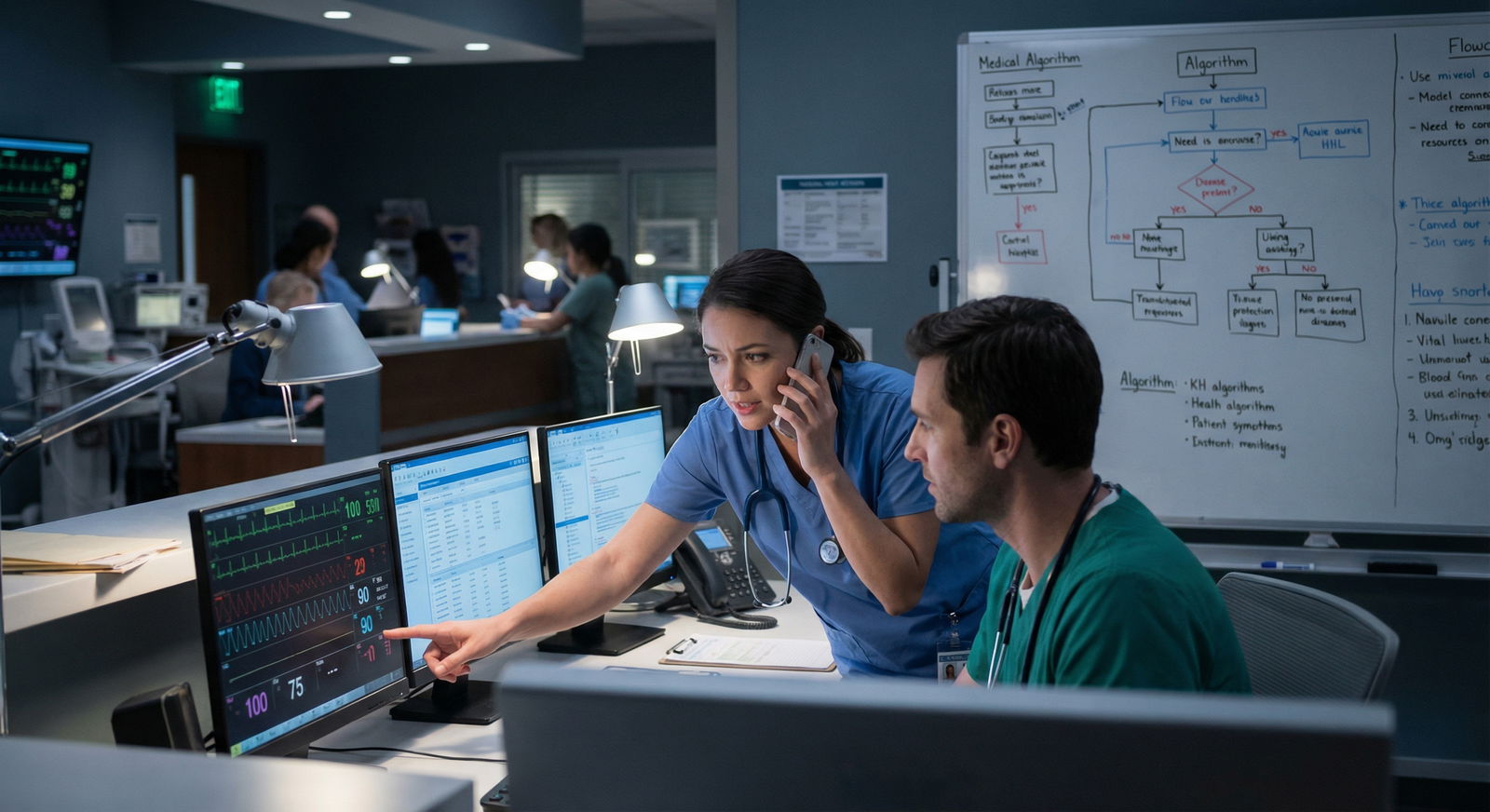

You need quick, dirty triage data. This is phone‑based battlefield medicine.

Have the charge nurse (or whoever is most competent and free) call both other units. You want a 20‑second report on each:

- Room #

- Age / basic problem (“post‑op day 1 hip,” “DNR COPD on 4L baseline,” “fresh chemo, neutropenic fever”)

- Primary concern (“SpO2 82%,” “SBP 70,” “unresponsive,” “HR 160s,” “staff worried”)

- Current vital signs (HR, BP, RR, SpO2, mental status in one sentence)

- Is primary team at bedside? Attending? Fellow?

If it’s a surgical unit at 3 a.m., there’s probably a chief resident lurking somewhere. Use them.

Have them write this on a scrap paper in huge letters and hand it to you. Do not rely on memory when you’re already knee‑deep in norepi and vomit.

Your mental question:

“Which patient is most likely to die in the next 5 minutes if no one more skilled than an intern touches them?”

That’s who gets you.

Step 3: Decide: stay, go, or split the team

There are exactly three moves, and you have to pick one fast:

- You stay at your current RRT and others are managed by surrogates.

- You leave this RRT (after minimal stabilization) to handle a clearly sicker one.

- You split if you’re lucky enough to have more than one capable responder.

How to decide:

You stay if:

- Active airway issue you’re personally managing (imminent intubation, agonal respirations, GCS dropping)

- Refractory hypotension requiring push‑dose pressors, pressor start, or central access

- Ventilated / trach patient decompensating

- Rhythm change concerning for need of shock / ACLS decisions

You can leave after a quick “stabilize and handoff” if:

- The patient is awake, talking, airway protected

- SBP is low but responding to a bolus and you have a clear plan written

- Issues are “moderately sick” but not “about to die” (e.g., new Afib with RVR in the 140s but stable BP, sepsis with borderline pressures but not crashing, etc.)

- You’ve ordered a clear, simple algorithm: “If SBP < 90 again, start norepi at X, call ICU attending.”

You split when:

- There’s another resident/fellow/NP/PA physically present or rapidly available

- An ICU attending is in house and can peel off to one RRT while you hit another

- ED doc or anesthesia can be borrowed to cover airway‑heavy RRT while you manage the others

Say your decision explicitly:

“Okay. I’m staying here. ICU fellow is going to 7 West. Surgery chief to 8 East. Everyone call me on speaker if things go south.”

This isn’t ego. It’s logistics.

Step 4: Use the “90‑second micro‑stabilize” strategy

Let’s say you decide you need to leave this room to go to another RRT. You still owe this patient 90 seconds of smart, high‑yield action before you run.

Those 90 seconds should look like this:

Airway / Breathing

- Sit them up if they can tolerate it

- Non‑rebreather on, max oxygen, maybe brief CPAP/BiPAP if that’s the main problem and they can cooperate

- Suction accessible, Yankauer in hand

- If they’re borderline airway and you’re leaving, that’s probably the wrong call. You stay.

Circulation

- Wide‑open fluids if hypotensive and not in florid pulmonary edema

- Two large‑bore IVs

- Push‑dose pressor ordered, mixed, and at bedside if needed

- Maintenance plan: “Start norepi at X if SBP < Y; titrate.”

Orders in the system before you walk:

- STAT labs: CBC, BMP, lactate, ABG/VBG, troponin, coags, cultures if sepsis suspected

- STAT EKG if rhythm/ischemia issue

- Imaging if clearly indicated (CXR portable, CT head for acute neuro change, etc.)

- Level of care: “Likely ICU transfer—call bed control now.”

Handoff script to bedside nurse:

- “Here’s the plan:

– Keep them on non‑rebreather

– Check BP every 5 minutes

– If SBP < 90, give another 500 cc, then start norepi per protocol

– I’m going upstairs to another RRT but I’m still your doc. Call my cell and overhead RRT if anything worsens suddenly (especially mental status or breathing).”

- “Here’s the plan:

You want the nurse to know you didn’t just bail. You left a plan, not a void.

Step 5: Get brutal about delegation

When multiple RRTs hit, you cannot be the note‑writer, IV placer, airway manager, and transport coordinator for all of them. That’s how you fail everyone.

Be that slightly bossy person. It’s fine.

Say things like:

- “You—start peripheral IV, 18 gauge or bigger. You—hang 1L LR wide open.”

- “Someone pull up the latest echo and EF on this patient on the computer next to me.”

- “Charge nurse—please call anesthesia and tell them we may need an airway in room 615 in the next 5 minutes.”

- “Med student—you’re now historian. Open the chart, find last H&P, and give me a 30‑second summary.”

You do doctor‑level work only:

- Deciding airway vs no airway

- Shock vs not shock

- ICU vs floor vs comfort care

- ACLS decisions

Everything else gets delegated ruthlessly.

Step 6: Use a dead simple triage framework

You don’t need a textbook. You need a sorting hat.

When you have 2–3 simultaneous RRTs, quickly sort each into one of these buckets:

| Level | Description | Your Priority |

|---|---|---|

| Red | Actively dying / unstable | You go personally |

| Orange | Potential to crash soon | You go second or phone-supervise closely |

| Yellow | Sick but stable | Supervise by phone, primary team + nurses manage |

Red = ANY of:

- Unresponsiveness / no meaningful airway reflexes

- SpO2 ≤ 85% on max oxygen or needing bagging

- SBP < 80 not responding to initial bolus

- Suspected stroke with rapidly worsening exam

- New chest pain + hypotension + arrhythmia

- Active seizure not stopping

Those are your immediate body‑in‑room cases.

Orange = could crash in the next hour:

- SBP 80–90 but mentating

- RR in the 30s–40s with work of breathing but talking

- New Afib with RVR, BP okay

- Sepsis with lactate but hanging in there

- Confused but protecting airway

Yellow = still need help, but not now‑now:

- Mild hypoxia that improves with nasal cannula

- HR 120s, BP fine, pain/anxiety likely

- Nurse‑driven RRT for “I don’t like how they look” but vitals okay

You can manage Yellow mostly by:

- Phone orders

- Clear algorithms with the bedside team

- Scheduling yourself to see them in person as soon as Red/Orange are settled

Step 7: Work the phones like part of your code cart

When everything is crashing, your phone becomes another piece of resuscitation equipment. Use it aggressively.

-

- Call ICU fellow/attending:

“We have three simultaneous RRTs: one probable intubation, one hypotensive septic, one arrhythmia but stable. I need another physician body or anesthesia in‑house STAT.” - This isn’t whining. It is patient safety.

- Call ICU fellow/attending:

Use speakerphone at the bedside.

If you’re overseeing another RRT remotely, put your phone on speaker so everyone hears the plan.

“Okay, I’m on the line. What are current vitals? What’s the mental status? Good. Here’s what we’re going to do…”Call primary teams, don’t just “page and pray.”

- “Hi, this is night float. Your patient in 732 is on an RRT. We’re worried. I’ve started X, Y, Z. I need you physically at bedside in the next 5–10 minutes or I’m going to escalate to ICU myself.”

Document the fact that you called and they’re aware. It protects you and, honestly, pressures them to show up.

Step 8: Decide who goes to ICU, who can stay, who needs goals‑of‑care ASAP

When you’re juggling multiple deteriorations, disposition is half the battle.

Use a fast, no‑nonsense framework:

ICU now (no debate):

- Pressor‑dependent

- Respiratory failure needing BiPAP beyond “trial” or intubation likely

- Unstable arrhythmias needing drips

- Continuous neuro monitoring after acute neuro change, especially if receiving tPA or post‑arrest

Stepdown / high acuity floor:

- Needs q2h vitals, frequent nursing but not pressors

- BiPAP but stable and improving

- Sepsis that responded well to first few liters and antibiotics

Same level of care but close watch:

- RRT triggered mostly on anxiety, pain, transient hypotension that corrected

- You set clear hold parameters (BP cutoffs, RR triggers, mental status concerns)

Goals‑of‑care urgent conversation:

- Frail, end‑stage, multiple prior ICU stays, and now crashing again

- Patient previously expressed “no tubes,” “no life support,” but chart is unclear

- Family present and already saying, “They wouldn’t want all this…”

If you see that last group in a multi‑RRT cluster, you need to mentally flag: I must talk to this family today, not “when everything calms down.” Because “everything” might not.

Step 9: Managing your own brain so you don’t lock up

Here’s what no one tells you: multiple RRTs don’t just stress your medical skills. They scramble your frontal lobe.

You’ll feel:

- Tunnel vision

- Time distortion

- Cognitive overload (can’t remember your own orders 2 minutes later)

You combat that with structure:

Use a pocket notepad or scrap paper.

Write:- RRT #1 – Room xxx – “airway,” “septic shock”

- RRT #2 – Room xxx – “Afib RVR, stable”

- RRT #3 – Room xxx – “AMS, likely metabolic”

Scribble what you’ve done and what still needs doing. Cross things off. Primitive but effective.

Force yourself to pause 5 seconds between rooms.

Literally stop in the hallway. Inhale, exhale, mentally reset: new patient, new story.

Residents who don’t pause start treating Room 732 with Room 815’s plan.Use the exact same mental schema every time.

ABCs, vitals, monitor, IVs, quick exam, key labs, disposition.

Don’t improvise a new checklist at 3:17 a.m. Use one.

Step 10: Common mistakes that make multi‑RRT nights worse

I’ve watched residents do these over and over:

Bouncing between rooms every 2 minutes with no real progress anywhere.

Pick a room. Do meaningful stabilization. Then move.Letting guilt, not physiology, decide where they go.

Just because you were called to 8 East first doesn’t mean they stay your top priority if 7 West has a pulseless rhythm.Trying to “be nice” and not waking backup.

Nobody cares at M&M that you didn’t wake the attending. They care that a patient died that didn’t need to.Forgetting to communicate that you’re “covering multiple RRTs.”

Nurses will assume you’re just weirdly slow unless you say:

“I’m currently managing three RRTs simultaneously. If I step out, I will come back. If something acutely worsens, call a code or overhead RRT again.”Not documenting key decisions.

You don’t need a novel at 4 a.m., but write:

“RRT activated for hypotension. Found SBP 70s, started 2L LR, norepi, called ICU, patient transferred. Concurrent RRTs in rooms X and Y, primary teams aware, ICU fellow involved by phone.”

CYA isn’t the primary goal, but future‑you will be glad past‑you wrote it down when everyone starts asking what happened.

A quick mental flowchart you can steal

Here’s how the night often really goes. Map yourself onto this.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | First RRT active |

| Step 2 | Second RRT overhead |

| Step 3 | Ask charge for brief report |

| Step 4 | Third RRT overhead? |

| Step 5 | Compare severity of 2 RRTs |

| Step 6 | Gather basic info on all 3 |

| Step 7 | Stay at current bedside |

| Step 8 | Stabilize 90 seconds then move |

| Step 9 | Call backup to other RRTs |

| Step 10 | Delegate tasks at each site |

| Step 11 | Decide ICU vs floor vs comfort |

| Step 12 | Document key actions |

| Step 13 | Current patient most unstable |

Read that a couple of times when you’re not tired. It will load automatically faster when you’re exhausted.

Training ahead: practice on “easy” nights

You cannot simulate three true train‑wreck RRTs on a calm day, but you can practice the pieces.

On slower calls:

- When one RRT fires, ask: “If two more dropped now, which things would I do first, which could be delegated, and what info do I absolutely need?”

- Start using the Red / Orange / Yellow framework even with single RRTs.

- Get comfortable saying out loud, “Here is the plan,” and assigning roles. That muscle memory matters when voices are raised and everyone’s panicking.

Ask your seniors, “What was your worst multi‑RRT night and what did you wish you’d done differently?” You’ll get real stories, and usually one or two tricks you can steal.

When the dust settles

After nights like this, you’ll be tempted to just pass out and never think about it again. Fight that impulse at least for 10 minutes.

Run a mental replay:

- Where did I waste time?

- Where did I hesitate too long to call for backup?

- Who did I not communicate with clearly?

- Which patient scared me most, and why?

If you can, debrief with a co‑resident or ICU fellow the next day. Two or three concrete adjustments now will make the next multi‑RRT storm much less chaotic.

Because there will be a next time.

The good news: each time you get through one of these nights, you’re less the intern finishing someone else’s orders and more the physician everyone in that overhead announcement expects will take charge.

Tonight might just be survival. But with this framework burned into your brain, the next time the speakers blast out “Rapid response x3,” you’ll feel something new under the anxiety.

A plan.

And once you’ve got that, you’re ready for the next layer of on‑call reality: juggling all this while the ED is trying to turf you four admissions and your pager won’t shut up. But that is another night’s problem—and another chapter in how you learn to survive residency on call.