The most dangerous resident is the one who’s afraid to wake their attending.

If you remember nothing else, remember this: you will never get in real trouble for calling too early, but you can absolutely wreck a patient (and your reputation) by calling too late.

Let’s go straight at the question you actually care about:

The One-Sentence Rule

If a reasonably careful attending would want to know right now, you wake them up. Full stop.

You’re not there to protect your attending’s sleep. You’re there to protect the patient and not practice outside your level.

Now let’s make that usable.

The Non-Negotiables: Always Call For These

If any of these are happening, you don’t “think about it,” you don’t “watch it for an hour,” you pick up the phone.

, New sepsis, Rapid AF with RVR, Acute chest pain, New neuro deficit, Major bleed](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_svg/chart-common-overnight-events-that-should-trigger-attend-8446.svg)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| [Code blue](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/residency-on-call-tips/what-attendings-really-judge-during-your-first-code-blue-night) | 100 |

| New sepsis | 95 |

| Rapid AF with RVR | 90 |

| Acute chest pain | 90 |

| New neuro deficit | 95 |

| Major bleed | 95 |

1. Anything that feels like “this could kill them in the next few hours”

Classic examples:

- Code blue or any peri-code situation

- New or worsening chest pain concerning for ACS

- Sudden respiratory distress, escalating O2 needs, or impending intubation

- New or worsening hypotension (MAP < 65 or SBP < 90) not quickly corrected

- Sustained tachycardia > 130 that isn’t obviously benign

- A patient you’re thinking about sending to the ICU or stepdown

If you’re wondering, “Is this sick-sick?”—call.

2. New sepsis or shock

Red flags that should trigger your “wake the attending” reflex:

- Fever + hypotension + tachycardia + suspected infection

- Lactate ≥ 2, especially if trending up

- You’re giving bolus after bolus of fluids or starting pressors (or thinking about it)

- Escalating O2 AND dropping pressures

If you’re initiating a sepsis bundle or wondering if they need ICU—attending needs to know, now.

3. Anything that might be a stroke or major neuro event

Don’t overthink this. Call for:

- New focal neuro deficits (weakness, facial droop, aphasia, visual changes)

- New-onset seizure

- Sudden severe headache (“worst headache of my life,” thunderclap, or with neuro changes)

- Acute change in mental status that’s not clearly explained and not minor

You’ll be calling neurology / stroke team anyway. Loop your attending in.

4. Big bleeds or major anemia

Wake them up for:

- GI bleed with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, or needing multiple transfusions

- Massive hemoptysis or any bleeding compromising airway

- Post-op bleed, expanding hematoma, or dropping hemoglobin with unclear source

- You’re ordering more than 2 units PRBCs or activating an MTP (massive transfusion protocol)

“Significant bleed” is not an attending-optional event.

5. Airway issues, real or impending

If you’re thinking “this person might need to be intubated soon,” that’s enough:

- Stridor, increased work of breathing, tripoding

- New wheezing with poor air movement, not responding to nebs

- Facial/neck swelling, angioedema, neck hematoma

- Any patient you’re calling anesthesia/ICU about for airway

You do not wait to see “how they do” for 2 hours.

The Gray Zones: Probably Call, Depending on Context

Here’s where residents get stuck. You’re afraid of over-calling but your gut is uneasy. This section is for that.

6. Any deterioration you can’t explain or reverse quickly

Examples:

- Stable patient becomes tachycardic, confused, or hypotensive without an obvious cause

- A-fib with RVR that isn’t controlling with first-line measures

- O2 needs creeping up over a few hours without a clear reversible trigger

- Sudden oliguria/anuria in a previously stable patient

You don’t need a complete diagnosis before you call. You need to recognize, “This is not right and I’m not fully in control of it.”

7. Big decisions that change level of care

If you’re about to:

- Transfer to ICU or stepdown

- Downgrade from ICU when you’re not totally convinced it’s safe

- Make a significant goals-of-care decision overnight

- Decide whether to intubate or not in a borderline situation

This isn’t your license. It’s your attending’s. Don’t unilaterally change the whole trajectory.

8. New serious diagnosis

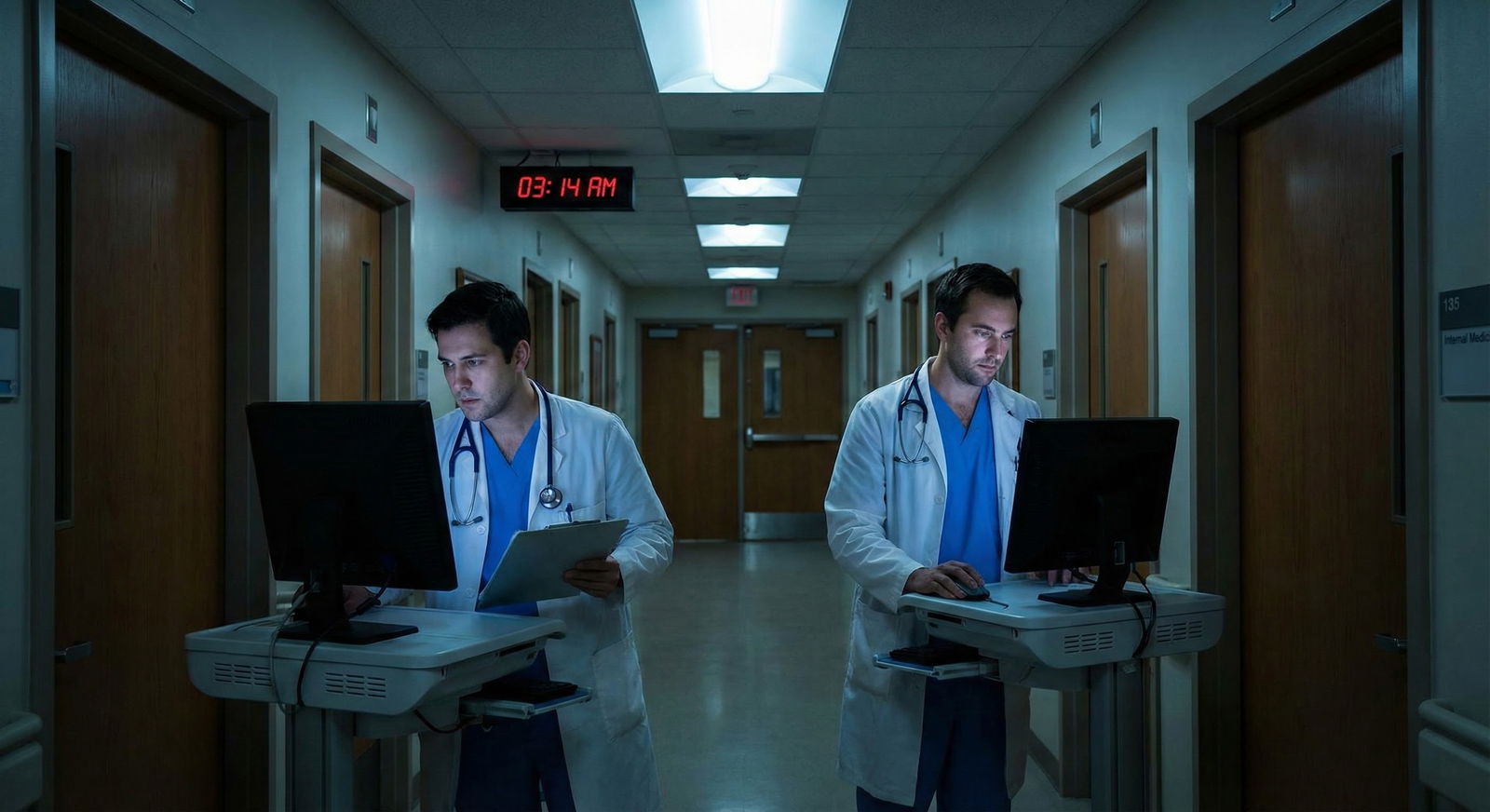

Even at 3 a.m., many attendings want to know about:

- New confirmed PE, stroke, STEMI, NSTEMI, or other major finding

- New cancer diagnosis from emergent imaging or labs

- Unexpected critical imaging/lab results that change management significantly

If you’re startled by the result and your management plan changed aggressively, it’s usually worth a call.

9. Uncomfortable consent or family dynamics

If you’re facing:

- A high-risk procedure consent where family seems confused or conflicted

- Escalating family conflict or accusations

- Threats of legal action or “I’ll sue the hospital”

- Requests for treatments you don’t think are appropriate

This is exactly the kind of scenario attendings want a say in. Don’t carry that solo.

Things You Usually Don’t Wake Them For (If You Have a Plan)

Let’s be honest: not everything needs an attending at 2 a.m. Part of growing up as a resident is learning what you can just handle.

| Issue | Usually Wake? |

|---|---|

| Mild asymptomatic hypertension | No |

| Single fever spike in stable pt | Usually No |

| Potassium 3.3 with CKD | No |

| Creatinine bump 0.3–0.4 | No (page in AM) |

| New AF with stable vitals | Depends, often yes |

| New O2 need from 2L to 3L | No if stable |

Reasonable not-to-wake examples (assuming you’re comfortable and patient is otherwise stable):

- Mild electrolyte abnormalities (K 3.1, Mg 1.5) that you correct per protocol

- Single fever spike in a stable, already-infected patient where you:

- Check cultures if needed

- Give fluids / antipyretics

- Reassess

- Mild BP issues (SBP 160–180 in an otherwise okay patient) that you adjust meds for

- Random “patient can’t sleep, needs melatonin” or “they want a different pain med” calls that you handle according to unit norms and safety

The trick: if the vital sign change or lab change implies organ damage, acute decompensation, or a potential crash in the next few hours—call. If it’s a small deviation that you can correct safely and recheck, you’re probably fine.

How to Decide in 30 Seconds: A Simple Escalation Framework

On call you don’t have 20 minutes to overthink every situation. You need a quick mental algorithm.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Notice problem |

| Step 2 | Stabilize and call attending immediately |

| Step 3 | Call attending after brief assessment |

| Step 4 | Discuss with senior then call if unsure |

| Step 5 | Treat, reassess, update in morning |

| Step 6 | Threat to life/limb/airway now? |

| Step 7 | Major change or level of care? |

| Step 8 | Clear protocol and patient stable? |

Run through this:

Is there an immediate threat to life, limb, or airway?

If yes: start stabilizing and call attending right away (and senior if you have one).Does this change level of care or represent a major new problem?

New ICU need, new serious diagnosis, large bleed, sepsis → call.Is there a clear protocol and the patient is otherwise stable?

If both yes: follow protocol, document well, and update in the morning.Still uneasy?

Call your senior first if you have one. If you are the senior and still uneasy, just call the attending. That’s the job.

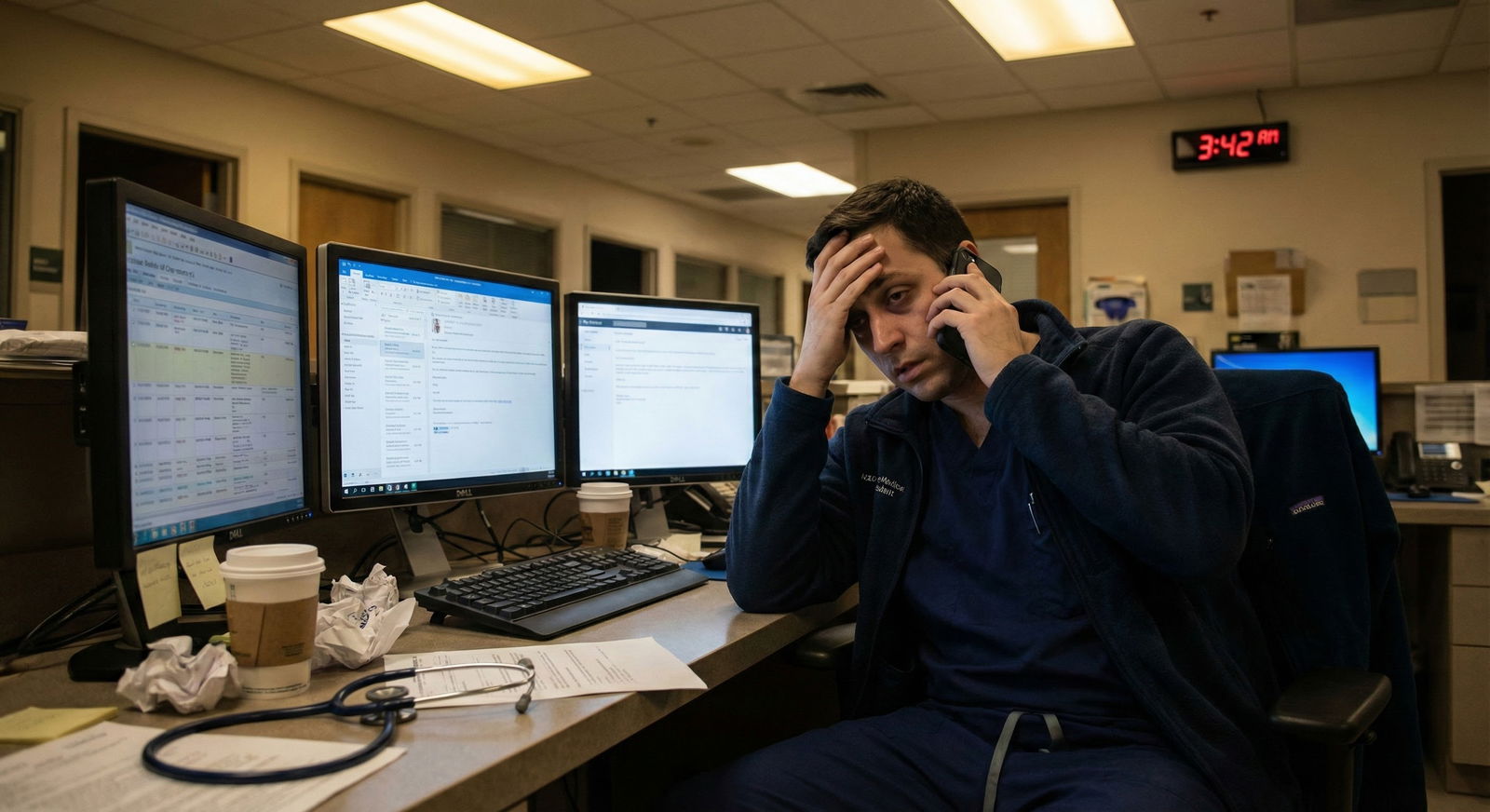

How to Wake Your Attending Without Sounding Lost

Content matters, but so does delivery. The fastest way to make an attending trust you is to call early and be organized.

Use a tight SBAR structure (yes, the classic, because it works):

S – Situation (1–2 sentences)

“Hi Dr. Lee, sorry to wake you. This is Dr. Patel, the night float on 7E. I’m calling about Mr. Johnson in 732, your 68-year-old with CHF and COPD, who’s now hypotensive and more short of breath.”

B – Brief Background (2–3 key facts)

“He was admitted two days ago with decompensated heart failure, on IV diuresis. Earlier today he was stable on 2L NC, BP 120s/70s. No known infection workup yet this admission.”

A – Assessment (what you’re actually seeing)

“Now his BP is 82/50, HR 118, RR 28, sat 90% on 4L, he’s more confused, and lungs are wetter on exam. I’ve given 500 cc LR, drawn stat labs and cultures, and ordered a chest X-ray. I’m worried about cardiogenic versus septic shock.”

R – Recommendation (proposed plan or ask)

“I think he needs either more fluids or pressors and probably ICU-level care. I’d like to run our next steps by you and see if you want to come in or if I should call the ICU team now.”

Key things that make this go well:

- Have the chart open and vitals in front of you

- Know code status

- Know recent labs, imaging, and major meds (pressors, anticoagulation, etc.)

- Have a proposed plan, even if it’s imperfect

You’re not graded on being right about the diagnosis. You’re graded on recognizing sick, acting fast, and not freezing.

Program Culture vs. Safety: Read the Room, But Don’t Be Stupid

Every attending has a different threshold. Some say, “Call me for literally anything that worries you.” Others say, “Don’t wake me unless someone is dying or going to the unit.”

That’s nice in theory. In reality, you:

- Follow explicit instructions given on day one (“Call me for X, Y, Z no matter what”).

- Learn individual preferences over time.

- But you never let “they hate being called” stop you from escalating real risk.

If you’re in a malignant-feeling culture where attendings shame people for calling, here’s the quiet reality: they’ll shame you ten times harder if a patient crashes and you didn’t call. Protect the patient first, protect your license second, worry about their ego third.

ICU vs. Floor: The Threshold Changes, But Not That Much

In the ICU, the baseline is “everyone is sick,” so your calling threshold shifts a bit:

- More leeway on borderline vitals you can adjust yourself (small pressor tweaks, ventilator changes per protocol).

- Less leeway on new failures: new organ failure, new arrhythmia, new bleed, or escalation beyond your comfort.

On the floor, the threshold is lower: sudden significant vitals changes, new O2 requirements, altered mental status—these should all at least make you think “Do I need to wake someone?”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Minor BP fluctuation | 20 |

| O2 escalation | 40 |

| Pressor change | 60 |

| New arrhythmia | 80 |

| New organ failure | 100 |

The Real Test: Your Gut + “Would I Defend This to QA?”

Here’s the internal script I’d use on call:

“If this went south and we were in M&M tomorrow, would I be comfortable saying I chose not to call?”

If the honest answer is no, you already know what to do.

And one more gut check: if you catch yourself thinking “I don’t want to bother them,” that’s the wrong variable. Replace that with “I don’t want to miss something dangerous.”

FAQs

1. What if I call my attending and it turns out to be nothing?

Then you did your job. Everyone who has practiced long enough has a pile of “false alarms.” The only people with zero false alarms are the ones who miss real problems. If an attending ridicules you for calling with a legitimate concern, that’s their professionalism problem, not your clinical error.

2. Should I call my senior first or the attending directly?

If there’s an in-house senior, start there unless the patient is actively crashing and there’s no time. Good pattern: stabilize → page senior STAT → both of you call attending together if needed. If you’re the senior, your threshold to wake the attending should still be low for real risk, big decisions, or anything that makes you think “I’m out of my depth.”

3. What if I’m truly unsure whether this is “sick enough” to call?

Ask yourself three questions:

- Is this clearly outside routine variation for this patient?

- Am I worried they could get significantly worse in the next few hours?

- Am I uncomfortable being the only one who knows about this right now?

If you get two yeses, call. When in doubt, say: “I think they’re okay right now but I’m worried about where this is headed.”

4. Do attendings actually want to be called overnight?

The good ones do. They’d much rather lose 10 minutes of sleep than lose a patient or have a preventable disaster. Most will explicitly say, “If you’re on the fence, just call.” The rare attending who doesn’t want to be bothered is precisely the person you need to protect yourself from by documenting well and calling anyway when it’s serious.

5. How do I document when I wake an attending?

Simple, clear, and defensive: brief note with time, issue, your assessment, what you did, and what you discussed. Example: “0300: Called Dr. Smith re: new hypotension and hypoxia in pt. Vitals…, exam…, labs pending. Given 500 cc LR, placed on 4L NC. Plan per Dr. Smith: trend vitals q15, repeat lactate, consider ICU transfer if MAP <65 despite 1L.” If it’s not in the note, it didn’t happen.

6. What if my attending gets angry or tells me I shouldn’t have called?

Stay calm. “Understood. I was concerned about X and didn’t want to miss anything. I’ll handle similar situations this way unless you’d prefer something different.” Then write down their stated preference. But don’t let that change your behavior when the patient is actually at risk. In the long run, people respect residents who put patient safety over politics.

Key points:

- You never get burned for calling too early on something real; you absolutely can for calling too late.

- Immediate threats to life, airway, circulation, or major changes in status = automatic wake-up call.

- When in doubt, ask: “Would I be comfortable defending not calling in M&M tomorrow?” If not, pick up the phone.