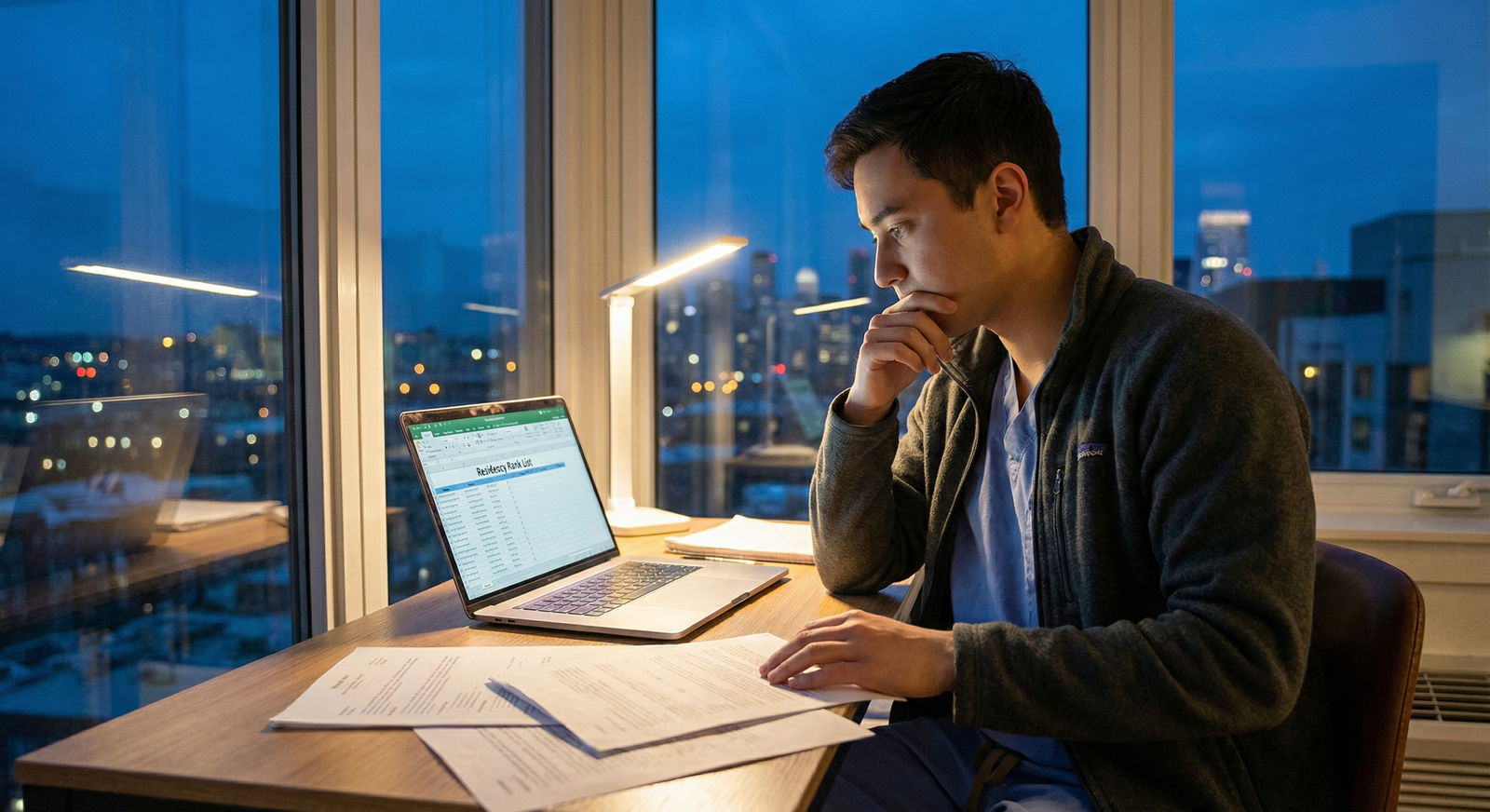

You’re sitting on your bed with your ERAS list open and the ROL portal blinking at you. Your classmates are stressing about prestige vs. location; you’re staring at a different column: “Can I actually survive here with my health and body?” Your diagnosis, flare risk, or disability isn’t theoretical. It’s whether you end up in the hospital as a patient instead of a resident.

If that’s you, this isn’t about “optimizing your rank list.” It’s about not wrecking your health and still matching into a program that will train you properly. Let’s walk through how to handle rank decisions when serious health issues or disabilities are part of the equation.

Step 1: Get ruthlessly clear on your non‑negotiables

Before you think about program reputation, prestige, or research, you need to draw a hard line: what will actually keep you functional and safe?

Do this before you open your rank order list. Otherwise you’ll talk yourself into compromises that look reasonable at midnight and destroy you by October.

Think in four buckets:

- Medical realities

- Workload / call structure

- Physical environment

- Support/attitude of the program

1. Your medical realities

Make a list that’s brutally honest, not aspirational.

Examples:

- “I have Crohn’s with flares triggered by sleep deprivation and missed meds.”

- “I’m deaf in one ear and use a hearing aid and captioning.”

- “I have a seizure disorder; I cannot safely drive.”

- “I’m post‑cancer treatment, high risk for infection, stamina limited.”

Then translate each into concrete needs:

- Max continuous hours you can realistically handle without breaking down

- How many nights in a row you can do before your condition spirals

- How often you need predictable clinic/infusion/therapy/medication times

- Any exposures that are dangerous: chemo agents, radiation, certain infections, anesthetic gases, etc.

Write them down as specific rules. “Need one half‑day per week for infusion hospital visits.” “Cannot safely do 28‑hour calls consistently; must have some flexible scheduling possibility.” If you don’t define it now, you’ll rationalize later.

2. Workload and schedule structure

You can’t always get perfect hours, but there’s a spectrum. On one side: malignant, 80+ “real” hours, lots of violation culture. On the other: programs that actually staff adequately and do not worship suffering.

Look at:

- Average hours per week (not what they say on interview day—what current residents say after you press them a little)

- Frequency and type of call: 24+ hour call vs. night float vs. shift work

- How often you’re cross‑covering multiple services at once

- Culture around “staying late to help” when the work is endless

For serious health issues, heavy 24‑hour call systems and routine 80‑hour weeks are a red flag. Not always a dealbreaker, but you better have a specific plan if you’re considering them.

3. Physical environment and accessibility

For disability involving mobility, vision, or hearing, the physical setup is not a detail. It’s survival.

Ask yourself:

- How far is the walk between ED, wards, ICU, and clinic? (I’ve seen residents walking 25–30 minutes one way across skyways in winter.)

- Elevators vs. stairs culture. Broken elevators that “everyone” just works around with stairs? Big problem.

- On‑call rooms: accessible? Close to patient care areas?

- Parking: can you get disability parking close to your work area, or is it at the edge of a massive complex?

- Conference rooms and rounds: AV, captioning, microphone use, functional Wi‑Fi for your assistive tech?

If you’re visually impaired, what’s the EMR interface like? If you’re hard of hearing, do they use masks with clear windows, microphones at conferences, video platforms with captioning?

4. Attitude and support

You can survive a lot with a program that genuinely wants you there and will problem‑solve with you. You cannot out‑plan a hostile culture.

Red/green flags to watch for:

- Vague “We’ll see what we can do if it becomes an issue” → red flag

- Clear: “We’ve had residents with X before, here’s how we handled accommodations with GME” → green flag

- PD or APD actually knows how to say “disability,” “accommodation,” “ADA” without flinching → green

- “We’re like a family, we all pitch in!” but no specifics on how they’ve supported anyone with real needs → often red

Step 2: Decide what (and when) to disclose

Now the messy part: how much do you tell programs before you rank, and to whom?

You have three different questions here:

- What do I tell on interviews (if those are still ongoing or future cycles)?

- What do I tell before I submit my rank list?

- What do I tell after Match Day?

On interviews

At this stage (for future readers more than current cycle), you’re balancing two risks:

- Not disclosing and ending up somewhere unsafe

- Disclosing and getting quietly ranked lower by biased people

Here’s the practical middle ground I’ve seen work:

- If your condition absolutely changes what specialties/rotations/call you can do (e.g., cannot do nights at all, cannot do certain procedural-heavy rotations), you should disclose something at the interview or in a private conversation with the PD or APD. Because otherwise you risk matching somewhere that physically cannot accommodate you.

- If your condition is serious but manageable with flexibility (e.g., autoimmune disease with occasional flares, hearing impairment that’s well‑supported with your tech), you can keep details minimal at interview and follow up after interviews with a more targeted email to PD or GME asking policy questions.

You don’t need to hand them your chart notes. You do need to be honest about functional limits.

A simple script by email or in a scheduled call:

“I live with a chronic health condition that’s stable with appropriate scheduling and access to care. I’d like to ask a few concrete questions about how the program and GME office have handled schedule modifications or disability accommodations for residents in the past.”

Then ask specifics, not vague “Are you supportive?” nonsense.

Before you submit your rank list

If you’re already at the rank-list stage, the question is this: do you need program‑specific answers to decide how to rank them safely?

If yes, your target is the PD and/or the institution’s GME office or ADA/Disability Services office, not random faculty.

You can:

- Request a confidential call with the PD

- Email GME directly for institutional policies

- Ask to be connected with the ADA/disability representative for residents

Be clear you’re not asking for special favors, you’re asking what’s already possible within their system.

Something like:

“I’m in the process of finalizing my rank list and I wanted to check how your institution handles formal accommodations for residents with chronic health conditions or disabilities. Specifically, I’m interested in:

– How schedule modifications are requested and approved

– Examples of accommodations that have been provided in the past (e.g., adjusting call, clinic days, assistive tech)

I’m happy to share more details privately if needed.”

Notice you didn’t reveal exact diagnosis unless you want to. You framed it around process.

After you match

This is when you go from hypothetical to concrete. After Match:

- Contact PD and GME/ADA office early (March/April), not the week before Orientation.

- Provide documentation from your treating physician spelling out functional limitations and suggested accommodations.

- Expect some back‑and‑forth. Institutions sometimes move slowly; push politely but firmly.

Make sure everything is in writing at some point. Verbal “Yeah, we’ll work with you” is nice until the chief resident changes and “forgets.”

Step 3: Gather real data on the programs you’re ranking

You cannot rank safely based on marketing slides and “our residents are like a family” speeches. You need actual intel.

Here’s how to get it.

Ask residents very targeted questions

Not: “Is the program supportive?”

Ask:

- “Have you seen the program adjust schedules or rotations when a resident had a health crisis, a complicated pregnancy, or needed FMLA?”

- “Has anyone in your program needed accommodations for a health issue or disability? How was that handled?”

- “If someone’s struggling physically, is the default ‘work through it’ or ‘let’s figure out a fix’?”

- “When people have serious life events—illness, family emergencies—does call actually get covered, or do people get guilted into working anyway?”

If no one can give you a single example of an accommodated resident in the last few years, assume one of two things:

- They’ve quietly pushed those people out.

- You might be the experiment.

Neither is ideal.

Use the “bad day” question

I always recommend this one:

“Tell me about the worst time someone’s health or personal life collided with residency here. What actually happened?”

You’re listening for whether leadership protected the resident or threw them under the bus.

- “She had a Crohn’s flare, PD arranged medical LOA, they redistributed call, she came back on a modified schedule” → strong sign.

- “We had someone burn out and they just kind of…left” with awkward silence → not reassuring.

Don’t ignore geography and health infrastructure

Look at the city itself, not just the hospital.

- Do they have subspecialists you need nearby (rheumatology, neuro, oncology, etc.)?

- Is there a tertiary center in‑house or across town that your insurance will cover as a resident?

- If you have rare disease or need infusions, will you be traveling 3 hours to get care? That will not be sustainable on 60–80 hours/week.

Step 4: Build a ranking framework that starts with survival

Now, how do you actually translate all this into a rank list?

You’re going to flip the typical order.

Most people:

- Prestige

- Location

- “Vibe”

You:

- Can I physically and medically survive 3–7 years here?

- Will I be trained well enough to practice my specialty competently?

- Everything else.

Create a tier system for your programs

Be blunt. Sort your programs into three groups based on your health/disability:

| Tier | Description | Rank Action |

|---|---|---|

| A | Safe & supportive: clear policies, positive examples, manageable workload | Rank as high as you like based on preference |

| B | Probably workable: some unknowns, mixed signals, but not clearly unsafe | Rank after Tier A, ordered by other priorities |

| C | High risk: malignant culture, no accommodations history, brutal schedule | Seriously consider leaving off your list |

How to categorize:

Tier A signs:

- You spoke with PD/GME and got clear answers about accommodations.

- Residents gave you at least one story of a colleague who was supported during illness/pregnancy/disability.

- Hours are demanding but not insane, and people actually go home post‑call.

- The city has the specialists and services you need.

Tier C signs:

- Repeated jokes about “we all lie on our duty hours.”

- Residents visibly exhausted, thin smiles, “it’s hard but it’s worth it” with dead eyes.

- No one can remember a single example of real accommodations.

- Leadership dodges questions about disability or responds with vague “we treat everyone the same.”

Do not be afraid to leave a program off your list altogether if it genuinely endangers your health. Matching into a program that will break you is not better than not matching. Scramble/SOAP into a safer place, do a prelim year, or take another path. That sounds dramatic until you’ve watched someone end up hospitalized, on a LOA, and then effectively forced out.

Weigh prestige very differently

Ask yourself: which is worse?

- Matching at a “top 10” name that runs you into the ground, triggers multiple hospitalizations, and leads to you resigning PGY‑2.

- Matching at a solid mid‑tier program that keeps you healthy, where you complete training and graduate as a competent attending.

I’ve seen both outcomes. The second is better. Every time.

If you’re dealing with real health limitations, “good enough training + survivable conditions” outranks “elite name + martyrdom.” That’s not settling. That’s you choosing to actually finish.

Step 5: Be strategic about specialty and track choices

This part is uncomfortable, but you’d rather wrestle with it now than during a crisis intern year.

Be honest about specialty demands

Some specialties are structurally more brutal in training: general surgery, ortho, neurosurgery, OB/GYN at many places. Some are more shift‑based with built‑in off time: EM, anesthesia in some institutions, certain fellowships later.

I’m not saying you “cannot” do a demanding specialty. I’ve seen residents with serious illnesses do surgery, ICU, you name it. But they always had one of two things:

- Unusually strong program support and flexibility

- Unusually stable disease and physical reserve

If your condition is already marginal on med school rotations, be realistic about multiplying that by 3–7 years.

Consider tracks and program types

Look for:

- Categorical positions vs. prelim/transitional years (a solid TY at a supportive community hospital may be a better PGY‑1 experience than a malignant categorical spot)

- Programs with night float vs. traditional Q3/Q4 24+ hour call

- Community vs. big academic—community can be more humane, but not always

You can also be strategic about your long game. Example:

- Internal medicine at a humane mid‑tier university program → later outpatient‑heavy fellowship or hospitalist job with more control.

- Psych at a program with strong outpatient focus if inpatient chaos is a health risk.

- EM at a place that enforces shift caps and built‑in recovery time if nights are an issue but shift work fits your needs.

Step 6: Plan for worst‑case scenarios at each program

This sounds dark. It’s actually how you take control.

For each program you’re seriously considering in your top 5–10, run this mental simulation:

“OK, if I match here and:

- My disease flares badly for 3 months

- I need surgery/chemo/a major workup

- My disability progresses and I need new accommodations

…then what?”

Do you:

- Have a subspecialist in that city or within a reasonable drive?

- Have a GME office that will process LOA and accommodations, or is everything “informal”?

- See any evidence that people have returned from LOA at this program successfully?

If the answers are all “I don’t know” for a given program, that program should not be above a place where the answers are mostly “Yes” or “Probably.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Program Support | 90 |

| Workload | 70 |

| City Healthcare | 80 |

| Physical Accessibility | 85 |

| Prestige | 60 |

Notice how “Prestige” is last? That’s the shift you need to make.

Also, ask bluntly:

- “What is your policy on medical leave for residents?”

- “Has anyone had to take a medical LOA in the last 5 years? Did they graduate?”

If they dodge, that’s an answer.

Step 7: Protect yourself emotionally while you do this

Let’s talk about the part no one puts in brochures: this is emotionally brutal. You’re watching classmates rank their fantasy programs without a second thought about whether they can physically handle it. You do not have that luxury.

Couple of things that help:

Stop explaining your every choice to classmates. You don’t owe anyone your health history. When they say, “You’re ranking X above Y?? But Y is more prestigious,” your script is:

“Yeah, I know. I just think X is a better fit for me.” Full stop.Have one or two people who know the full story. A mentor, a physician, or a friend who won’t try to talk you into unsafe decisions because they’re dazzled by big names.

Get your own doctors involved. Run your proposed top 3–5 by the specialist who actually treats you. Ask:

“If I live in City A vs. City B, working 60–80 hours/week, which is less likely to land me in the ICU?”Accept trade‑offs without self‑hate. Choosing a safer program does not mean you “couldn’t hack it.” It means you’re working within real constraints and still moving forward. That’s what grown professionals do.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | List all programs |

| Step 2 | Identify health/disability needs |

| Step 3 | Gather data from residents & PD |

| Step 4 | Tier A or B |

| Step 5 | Consider Tier C or remove |

| Step 6 | Rank based on safety then training |

| Step 7 | Move low or off list |

| Step 8 | Submit rank list |

| Step 9 | Program can meet needs? |

Step 8: When in doubt, choose the place that treats you like a human now

Pay very close attention to how programs behave before you’re theirs. That’s the best predictor of how they’ll act when you’re vulnerable as a resident.

Signs you should move a program up:

- PD answers your tough email with specifics, not fluff.

- GME replies promptly and offers to hop on a call.

- Residents talk about sick colleagues with compassion, not annoyance.

- No one pressures you to overshare, but they make it clear they’ll work within the system for you.

Signs you should move a program down or off:

- Your reasonable questions about accommodations go unanswered or get pushed off.

- You hear “We’ve never had to deal with that” said like a problem, not a challenge they’re open to.

- Residents brag about working through illness as a badge of honor.

- You get even a faint whiff of ableism or stigma when disability is mentioned.

Programs don’t suddenly become humane after July 1st. If they’re dismissive now, they’ll be worse when they hold your contract and evaluation in their hands.

The bottom line

Three things to walk away with:

- Rank survival and support above prestige. A completed residency from a solid, humane program beats burning out or breaking down at a brand‑name institution. Every time.

- Get real information, not vibes. Talk to residents, PDs, and GME/ADA. Ask blunt, specific questions about how they’ve handled illness and disability in the past.

- Do not be afraid to leave unsafe programs off your list. Matching into a place that will destroy your health is not a win. You are allowed to build a career that you can physically and mentally survive.