The pass/fail Step 1 era is going to expose weak clinical reasoning faster, not slower.

You will not be rescued by a three-digit score anymore. Programs are going to look straight through to how you think with patients, often earlier than you are being trained to handle.

Let me break down how to fix that. On purpose. Early.

1. What Changed With Pass/Fail – And Why Your Brain Needs To Change Too

Everyone repeats the same tired line: “Now that Step 1 is pass/fail, you can relax and focus on learning, not scores.”

That sounds nice. It is also how you end up as the M3 who knows every cytokine but cannot decide whether to order a CT or do nothing.

Here is what actually shifted in the Step 1 pass/fail era:

- Step 1 still tests complex pathophysiology and mechanisms.

- Step 2 CK now carries more weight for residency screening.

- Program directors increasingly care about whether you can “think clinically” as an M3–M4.

- Schools are not uniformly good at building explicit clinical reasoning skills early. Many still hide behind “systems-based” preclinicals and hope it somehow transfers.

What this means for you:

If you treat preclinical as a pure memorization playground because “Step 1 is just pass/fail,” you will bleed later when cases suddenly demand prioritization, diagnostic strategy, and management reasoning.

Early USMLE-style drills are how you close that gap before it hurts.

Not more Anki. Not more fact-stacking. Structured, short, ruthless clinical reasoning drills aligned with how Step 1 and Step 2 vignettes are actually built.

2. What “Clinical Reasoning” Really Means On USMLE-Style Questions

Let me strip the buzzwords. On boards, “clinical reasoning” boils down to two things:

- Can you recognize what problem is really being tested?

- Can you execute the minimal safe chain of thought to get from presentation → decision?

USMLE is not asking:

“Do you know everything about heart failure?”

It is asking:

“Given this 62-year-old with dyspnea and orthopnea who just started a new drug, what do you do next and why?”

That typically compresses into 4 concrete reasoning moves:

- Problem representation

- Hypothesis generation + ranking

- Discriminating features

- Action selection (diagnostic or therapeutic)

Let’s walk through these with Step-style framing.

2.1 Problem Representation

If you cannot summarize the case in 1 line, your brain is already losing.

You want something like:

“Elderly hypertensive man with acute-on-chronic progressive dyspnea and orthopnea after medication change.”

That one-liner:

- Sets age, risk factors, time course, and trigger.

- Prunes your mental list immediately. You are not thinking asthma anymore. You are thinking heart failure, medication side effect, ischemia.

USMLE does this to you constantly. Vignette bloat is designed to punish students who read passively instead of compressing the case.

2.2 Hypothesis Generation + Ranking

You are not listing 20 diagnoses. You are ranking 3–5.

For the example above:

- Decompensated systolic heart failure (top)

- Medication-induced fluid retention (e.g., NSAIDs, thiazolidinediones)

- Acute coronary syndrome presenting as dyspnea

- COPD exacerbation (lower given orthopnea, medication trigger, etc.)

On exams, this step is often implicit. You never write your differential, but your leading diagnosis controls the rest of your answer choices.

Weak students skip this step and chase answer choices instead. Strong students mentally pick a most-likely diagnosis even before seeing the options.

2.3 Discriminating Features

This is where early clinical reasoning training pays off.

For each top hypothesis, ask:

“What 2–3 findings in this stem specifically argue for or against this diagnosis?”

For decompensated heart failure:

- For: orthopnea, PND, history of MI, S3, rales, elevated JVP, peripheral edema.

- Against: completely normal exam, no volume signs, acutely pleuritic chest pain, high fever.

Drills here are simple: you read a question, and before looking at the answer choices, you say out loud or write:

“Most likely X because of A, B, and C.”

Then you check if your brain and the testwriter agree.

2.4 Action Selection

This is where USMLE separates people who truly reason from those who memorized laundry lists.

There are three recurring “action” patterns:

- What is the most likely diagnosis? (path or named disease)

- What is the best next step in management? (diagnostic or therapeutic)

- What is the underlying mechanism / risk factor / complication?

Clinical reasoning drills must get you fast at mapping from pattern → appropriate type of action.

Example:

- Stable patient, likely diagnosis clear, no red flags → outpatient test or conservative mgmt.

- Unstable patient (hypotension, altered mental status, airway risk) → immediate stabilization before any fancy imaging.

- Likely diagnosis but no confirmatory testing yet → pick the most specific, least invasive confirmatory test.

Early in M1–M2, you will not know every test. That is fine. What matters is that you start to categorize actions: stabilize vs diagnose vs treat vs defer.

3. Why You Must Start This In Preclinical – Even With Limited Knowledge

I keep hearing: “We are still in M1, we do not know enough to do cases yet.”

That is backwards. You need to practice how to reason long before you know everything.

Here is the important distinction:

You can drill the structure of reasoning even when you are fuzzy on the content.

Meaning:

- You may not know all the causes of nephrotic syndrome.

- You can still practice: this is chronic edema + proteinuria + hyperlipidemia → syndrome recognition → likely test → highest-yield path mechanism.

Think of it like weightlifting:

- Early phase: you are learning movement patterns (squat, deadlift) with low weight.

- Later phase: you add heavy plates (pharm details, rare diseases).

If you wait until M3 to “add” clinical reasoning, you end up trying to learn both movement and heavy load at the same time. That is when students break.

4. A Concrete Weekly Drill Framework (M1–M2, P/F Step 1 Era)

You need a system, not random UWorld shots when you feel guilty.

Here is a realistic drill structure for a preclinical student in the pass/fail era. Adjust the volume, but keep the pattern.

4.1 Core Principle: Short, Intentional, Daily Micro-Drills

Do not turn this into another 4-hour marathon that you avoid.

Do 15–25 minutes a day, 5–6 days a week, with:

- 3–5 full USMLE-style questions

- Strict process: predict → reason → then answer

- Brief post-hoc analysis focused on reasoning, not just “I got it wrong.”

By the way, this works best if you tie it to a fixed anchor: after lunch, first thing in the morning, or pre-dinner.

4.2 Example Weekly Schedule

| Day | Time (min) | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | 20 | New questions, cardio |

| Tuesday | 20 | New questions, renal |

| Wednesday | 20 | Mixed review, timed |

| Thursday | 20 | New questions, heme/onc |

| Friday | 25 | Error log + pattern review |

| Saturday | 15 | 2–3 questions, low-intensity |

This is not about question count. It is about the quality of how you walk through each case.

5. The Exact Stepwise Method For Each Drill

Let’s get precise. One question. What do you do?

Step 1 – One-Liner Before Anything Else

Read the stem once (no options yet). Then force a one-line summary:

“Middle-aged woman with subacute fatigue, pruritus, pale conjunctiva, heavy menses.”

Write or say it. This feels slow at first. In 3–4 weeks it becomes automatic.

Step 2 – Provisional Diagnosis + Rationale

Ask: “What do I think this is?” Then justify with 2–3 findings.

Example:

- “Likely iron deficiency anemia due to heavy menses, fatigue, pallor, maybe low MCV.”

- “Could also be hypothyroidism with menorrhagia, but anemia-focused stem suggests iron first.”

If you genuinely do not know the diagnosis, still practice:

- “Syndrome of chronic anemia”

- “Likely related to blood loss vs hemolysis vs decreased production.”

You are rehearsing structure even when content is missing.

Step 3 – Predict the Question Type

Before you look at options, ask: what kind of thing are they going to ask me?

- Dx name?

- Best next diagnostic test?

- Best initial treatment?

- Underlying mechanism / enzyme / receptor?

- Most likely complication?

For Step 1-era questions, it is often diagnosis or mechanism. For Step 2 CK-style cases, more often management.

This prediction matters. It forces you to anticipate the logical next step, which is exactly what real clinical reasoning is.

Step 4 – Answer Choice Dissection

Now you look at answers.

Your job is not just to pick. Your job is to:

- Eliminate explicitly: “Not this because…”

- Confirm your reasoning: “This matches my expected test / treatment.”

- Stop being seduced by buzzwords alone.

The discipline here is to avoid pure pattern-matching. You should be able to defend your choice and your rejections.

Step 5 – Post-Question Debrief (The Part Most People Skip)

You review the explanation. Not just the right answer, but:

Ask yourself three specific questions:

- Did I correctly identify the core problem early?

- Did my provisional diagnosis match the explanation’s framing?

- Where did my reasoning chain break? (representation, differential, key feature, or action)

If you track this, even roughly, you start to see patterns:

“Every time I misread time course, I blow the diagnosis.”

“Every time there are vitals abnormalities, I forget to prioritize stabilization.”

That is clinical reasoning calibration. And it is what you want.

6. What To Use For Drills (And What Not To Waste Time On)

Resources matter. Some are good for memorization. Some are good for reasoning. A few do both.

For early clinical reasoning drills in the Step 1 P/F era:

Strong Resources

- UWorld (yes, even early, in low volume)

- NBME-style questions (school-provided or purchased CBSE forms)

- AMBOSS (solid for reasoning layers and stratified difficulty)

- Some school-created “case of the week” vignettes, if they mimic USMLE structure

Weak Resources For This Purpose

- Pure flashcards / Anki without context

- Single-sentence quiz bank items that ask for random facts

- Old-school “question per line” review books without real stems

Those may help memory. They do almost nothing for pattern recognition, prioritization, or action selection.

If you want hard numbers: 80–90% of your “reasoning drill” questions should come from UWorld/NBME/AMBOSS-style stems, even if you are doing them slowly and in low volume.

7. How This Actually Looks: Worked Case Examples

Let me show you exactly how I would run a reasoning drill, early preclinical level, with limited knowledge. We will start simple and escalate.

Case 1 – Basic But Structured

A 56-year-old man comes to the clinic with shortness of breath when walking up stairs, swelling in his ankles, and needing 3 pillows at night to sleep. He had a myocardial infarction 2 years ago. On exam, his blood pressure is 140/85 mm Hg, pulse 92/min, respiratory rate 20/min. Bibasilar crackles are heard, and pitting edema is present in both legs.

Question: Which of the following pathophysiologic changes is most likely present?

Options (simplified):

A. Increased left ventricular ejection fraction

B. Decreased left ventricular contractility

C. Increased plasma oncotic pressure

D. Decreased pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure

Reasoning drill:

One-liner:

“Middle-aged man with history of MI and chronic exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, and edema.”Provisional diagnosis:

“Chronic systolic heart failure due to ischemic cardiomyopathy.”

Why? Dyspnea, orthopnea, PND-equivalent, MI history, rales, edema.Predict question type:

“Mechanism level: pathophysiologic change in HF.”Answer logic:

Systolic HF = decreased contractility → decreased EF, increased LVEDV, increased pulmonary capillary pressure. So best match: decreased LV contractility → pick B.Debrief:

Did the question test recognition of “heart failure” and mapping to mechanism? Yes.

What would a weaker student do? Either pick something about hydrostatic pressure without clarifying which compartment, or get lost in details.

Even if you did not remember all the hemodynamics, the abstract reasoning “damaged muscle contracts less well” gets you to B.

Case 2 – Early Management Thinking

A 72-year-old woman presents with sudden-onset shortness of breath and right-sided pleuritic chest pain. She returned from a 10-hour flight 2 days ago. Temperature is 37.0°C, BP 110/70, pulse 110/min, respirations 26/min, SpO₂ 90% on room air. She has mild swelling of the right calf.

Question: What is the best next step in management?

Options (simplified):

A. CT pulmonary angiography

B. Lower extremity venous Doppler ultrasound

C. Start IV heparin therapy

D. D-dimer level

Reasoning drill:

One-liner:

“Elderly woman with acute pleuritic dyspnea after prolonged immobilization, tachycardic, hypoxic, with unilateral leg swelling.”Provisional diagnosis:

“High suspicion for pulmonary embolism.”Predict question type:

“Best next diagnostic or management step based on pretest probability and stability.”Reason:

She is tachycardic, tachypneic, and hypoxic but still hemodynamically stable (BP OK). High pretest probability for PE.

Algorithm:

- High suspicion, stable → CT pulmonary angiography to confirm.

- Very unstable (shock, severe hypotension) → consider immediate anticoagulation/lysis.

So the best next step: CT pulmonary angiography (A).

What if someone picked D-dimer?

D-dimer is useful in low probability patients to rule out PE. In high probability, a negative result would not be trusted, and you still need imaging. That is a reasoning error.

- Debrief:

Where is the reasoning skill? Recognizing probability category (low vs high) and mapping to the correct test. That structure is the same across many diseases: low-risk → sensitive screening test; high-risk → more specific confirmatory test.

You can rehearse that pattern early even with only a partial understanding of PE itself.

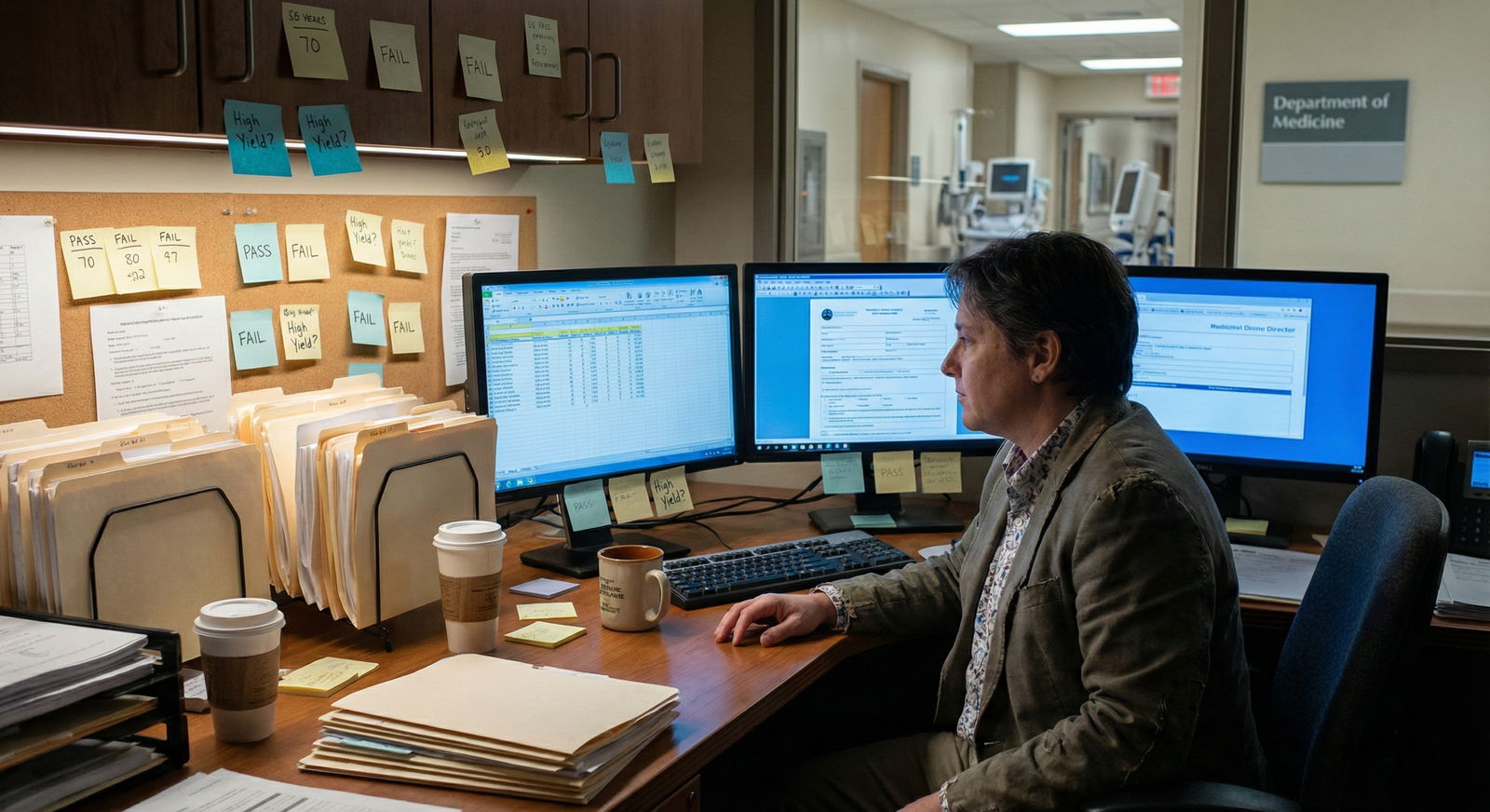

8. Common Failure Patterns I See In The P/F Generation

I have watched a lot of M2s and M3s in the P/F era. A few recurring problems are almost universal among those who struggle on Step-style clinical vignettes.

8.1 “Facts Without Hierarchy”

They know 20 causes of nephrotic syndrome but cannot decide which 2 are most likely in a given patient.

What they lack:

- Problem representation

- Pretest probability thinking

- Willingness to commit to a ranked differential

Fix: force yourself to always name a #1 and #2 diagnosis in drills, not just a word salad.

8.2 “No Time Course Awareness”

Students read “acute,” “subacute,” and “chronic” as noise.

On exams, they are not noise. Time course is a top-tier discriminator:

- Acute hours–days: infection, ischemia, torsion, PE, acute inflammation.

- Subacute days–weeks: post-infectious, evolving masses, autoimmune flares.

- Chronic months–years: degenerative, metabolic, genetic, long-standing autoimmune.

If you start annotating every case with time course during drills, your reasoning tightens fast.

8.3 “Vital Signs Blindness”

This one is brutal.

USMLE purposely hides the most important clue in plain sight: vitals.

- Hypotension + tachycardia → shock red flag. Stabilize.

- Fever + tachycardia + hypotension → sepsis pattern.

- Normal vitals → outpatient-level problem or non-emergent evaluation more likely.

If you find yourself jumping directly to diagnosis without scanning vitals, you are training the wrong brain circuit.

9. Integrating This With Your Actual Curriculum (Without Burning Out)

You have exams, labs, group sessions, maybe research. You do not need another full-time project.

You do need alignment.

Here is how to layer clinical reasoning drills without wrecking your life:

9.1 Tie Drills To Your Current System

Studying cardio?

- Do 3–5 UWorld/AMBOSS cardio cases every other day.

- Focus on: chest pain patterns, dyspnea patterns, syncope differentials, HF mechanisms.

Studying renal?

- Focus on: acute kidney injury (pre-renal vs intrinsic vs post-renal), nephritic vs nephrotic, electrolyte emergencies.

This way, your cases double as content review and reasoning practice.

9.2 Use Group Sessions Properly

Most small groups devolve into one person talking and everyone else zoning out.

Flip it:

- Before discussing as a group, everyone silently writes a one-liner and a top diagnosis.

- Then share and compare. Where do representations differ? Who is overcomplicating it? Who is missing the key discriminating feature?

You get more reasoning reps this way than from passively watching someone diagram a case on the board.

9.3 Track Patterns, Not Percentages

Stop obsessing over “I got 60% on this random UWorld block.”

At the M1–M2 pass/fail Step 1 stage, your key metrics should be:

- Do I always form a one-liner?

- Can I reliably identify the type of next step (stabilize vs test vs treat)?

- Do my missteps cluster around misreading time course / vitals / risk factors?

That is the kind of growth that actually makes Step 1 less scary and Step 2 CK much more manageable.

10. How This Pays Off When Step 2 CK Actually Matters

Program directors are blunt. Now that Step 1 is pass/fail, they stare harder at:

- Step 2 CK score

- Clerkship performance

- Letters commenting on your clinical reasoning

The exact drills we are talking about directly feed both.

10.1 CK Question Structure: Same Skeleton, More Management

Step 2 CK takes the same case logic and simply moves you one step downstream:

- Instead of “What is the diagnosis?”

- You get “What is the best next step in management?”

The early habits you build:

- One-liner

- Risk stratification

- Probability-informed action selection

Those become your superpowers when vignettes get longer and expectations higher.

10.2 Clinical Rotations: Attendings Care About Your “Reasoning Note”

When you present a patient, you are doing a spoken version of a USMLE question:

- Chief complaint → stem.

- Hospital course → added noise.

- Assessment and plan → answer choice + reasoning.

Attendings love students who:

- Represent the problem succinctly.

- Offer a plausible differential with ranked likelihood.

- Propose a next step that actually fits the patient’s stability and context.

Early USMLE-style reasoning drills train the exact cognitive pattern behind that. You are not “studying for a test”; you are practicing how your brain will work on rounds.

11. Mapping Cognitive Load Over Time

To make this concrete, think of your progression like this:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Early M1 | 80 |

| Late M1 | 65 |

| M2 | 50 |

| Early M3 | 35 |

| Late M3 | 25 |

You want:

- Memorization load dropping from ~80% of effort in early M1 to ~25% by late M3.

- Reasoning load growing in that freed mental space.

If you do not start early drills, the memorization line stays high too long. Then Step 2 CK and clerkships slam into you while you are still stuck in “what is this fact” mode instead of “what should I do for this patient” mode.

12. A Simple Visual For Your Personal Drill Workflow

Here is a stripped, honest version of what your daily case workflow should look like.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Read stem once |

| Step 2 | Form one liner |

| Step 3 | Provisional diagnosis and rationale |

| Step 4 | Predict question type |

| Step 5 | View answer choices |

| Step 6 | Select and justify |

| Step 7 | Review explanation |

| Step 8 | Identify reasoning error point |

If your current process does not look like this – if it goes: “Read → panic → scan answers → pick buzzword” – then you are reinforcing bad habits.

13. Advanced Twist: Self-Generated Micro-Vignettes

One more lever, for when you want to push yourself.

Once you have done a few hundred questions, start doing this once or twice a week:

- Take a disease you just reviewed (e.g., Graves disease, COPD exacerbation).

- Write a 3–4 sentence mini-vignette in USMLE style. Include: age, sex, 2 risk factors, key symptoms, a critical vital sign, 1–2 targeted exam or lab findings.

- Then write ONE correct “next step” or mechanism, and 3–4 plausible distractors.

This does two things:

- Forces you to think like the testwriter about discriminating features.

- Deepens pattern recognition because you decide which details really matter.

Most students never do this. The ones who do tend to crush both standardized exams and case-based oral assessments.

14. Quick Reality Check – What “Enough” Looks Like

Let me be blunt so you do not overdo it:

You do not need to:

- Finish UWorld twice in M1.

- Turn every lecture into a 20-case problem set.

- Spend 3 hours a day on clinical reasoning drills.

You do need:

- Consistent, small, high-quality exposure to real vignettes every week.

- A repeatable process for working through each case.

- Honest post-hoc reflection on where your reasoning breaks.

If you can do 3–5 real USMLE-style questions a day with full reasoning, for 5 days a week, over 40 weeks of preclinical, that is:

- ~800–1000 vignettes processed with a structured reasoning mindset.

That is more than enough to change how your brain sees patients and stems.

15. Final Thoughts

Three things I want you to walk away with:

- Pass/fail Step 1 did not make clinical reasoning less important. It shifted the spotlight onto it.

- You can and should train clinical reasoning early, even when your knowledge is incomplete, by drilling the structure: one-liner → top diagnosis → key features → action.

- Short, consistent, USMLE-style reasoning drills, done properly, will compound into better Step 1 performance, stronger Step 2 CK scores, and much smoother clerkships.

You cannot cram this skill in the month before CK. Build it now, in small daily reps, while everyone else is still hiding behind Anki decks.