The worst decision you can make in a malignant residency program is pretending it’s “just residency” and doing nothing.

If you’re reading this, you already know something is wrong. Not just “it’s hard.” Residency is supposed to be hard. What you’re feeling is different: dread on your days off, constant anxiety, maybe thoughts like, “If I had a car accident and ended up in the ICU, at least I’d get a break.”

That’s not normal. That’s your mind waving a red flag.

This is about one thing: should you transfer programs or stick it out—and how to make that decision like a rational adult, not a trapped intern spiraling at 2 a.m. in the call room.

We’ll walk through what “malignant” actually means, how burned out you really are, what’s fixable vs not, and how to think clearly about the transfer question.

Step 1: Get Honest About What “Malignant” Means in Your Case

Every intern calls their program malignant at 3 a.m. after a bad code. Ignore that noise.

A malignant program is not just busy or demanding. It’s a pattern of:

- Systematic disrespect

- Unsafe expectations

- No recourse or psychological safety

Run your situation through a quick reality filter.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Chronic Duty Hour Violations | 80 |

| Retaliation for Reporting | 60 |

| Humiliation Culture | 75 |

| Unsafe Staffing | 70 |

| No Schedule Flexibility | 55 |

Now, specifics. Malignancy usually shows up in 3 domains:

Workload and safety

- Routine, unreported duty hour violations (90–100+ hour weeks are “normal”)

- You are consistently responsible for unsafe patient loads

- You’re pressured to cut corners: skipping exams, pencil-whipping notes, unsafe discharges

- You dread signing orders because you know no one is backing you up

Culture and leadership

- Attendings regularly humiliate residents in front of others (“How did you even get into this program?”)

- Retaliation if you raise concerns (sudden bad evals, schedule punishments, ignored emails)

- PD and chiefs are openly dismissive: “This is residency. Toughen up.”

- No one high up seems to care about ACGME rules except on paper

Support and development

- You never get actual teaching; you’re just free labor

- No mentoring, no one to ask for help without being made to feel stupid or weak

- Evaluations are vague, punitive, or weaponized

- Chronic chaos: schedules last minute, rotations shuffled without notice, days off yanked

If you’re nodding “yes” to multiple bullets in each category, you’re not just in a hard program. You’re in a malignant one. That matters, because staying in a malignant environment long-term is a health decision, not just a career decision.

Step 2: Separate Three Problems: The Program, The Specialty, and Your Own Burnout

People blend these into one giant mess: “I hate everything, what if I chose wrong, maybe I’m not cut out for this.” That confusion keeps you stuck.

You have three separate questions:

- Is my program toxic?

- Am I still aligned with my specialty?

- Am I experiencing burnout, depression, or both?

You can hate your program and still love your specialty.

You can love your specialty and still be clinically depressed.

You can be burned out and still be in an objectively malignant program.

Let’s untangle.

2A. Check the specialty question

Ask yourself:

- On your better days, when someone’s actually teaching—do you find the clinical work interesting?

- When you picture yourself at 40, outside this program—can you imagine being fulfilled in this field at a better hospital with better colleagues?

- Strip away the toxicity: if you had decent hours, respectful attendings, and some teaching, would you want to keep doing this specialty?

If the honest answer is “Yes, I’d still want this specialty,” then the problem is where you are, not what you chose.

If the answer is “Even if things were good, I wouldn’t want this,” that’s a separate conversation (switching specialties). Different decision tree. Don’t mix it with the transfer decision.

2B. Check the burnout/depression question

Burnout and depression often coexist. Residency amplifies both.

Watch for:

- You feel emotionally flat or hopeless almost every day

- You cry in your car before or after shifts, frequently

- Sleep is wrecked: insomnia or crashing endlessly on days off

- You’re withdrawing from friends/family because you “don’t have the energy”

- Thoughts that others “would be better off without me,” or wishing something would happen so you wouldn’t have to go to work

That last one is not “just tired.” It’s danger territory.

You can’t make a clean decision about transferring if your brain is underwater. That’s like doing long division in a storm. You’ll either catastrophize or cling to the status quo just to avoid another change.

So you need to treat your mental state as aggressively as you’d treat DKA:

- See an actual therapist, preferably one familiar with residents

- Talk to your own physician (or get one) for screening and possibly meds

- Take the Employee Assistance Program (EAP) seriously if it’s not just a sham

- At minimum: tell one trusted person what’s really going on

This isn’t optional. I’ve seen residents decide to “just survive” a malignant program and end up leaving medicine entirely because no one caught the depression early.

Step 3: Map Your Reality—Don’t Trust Your 3 A.M. Brain

Right now, your brain is running on cortisol and resentment. It will tell you either “Everything is impossible” or “If I just try harder, it will magically fix.” Both are lies.

You need data. Not vibes.

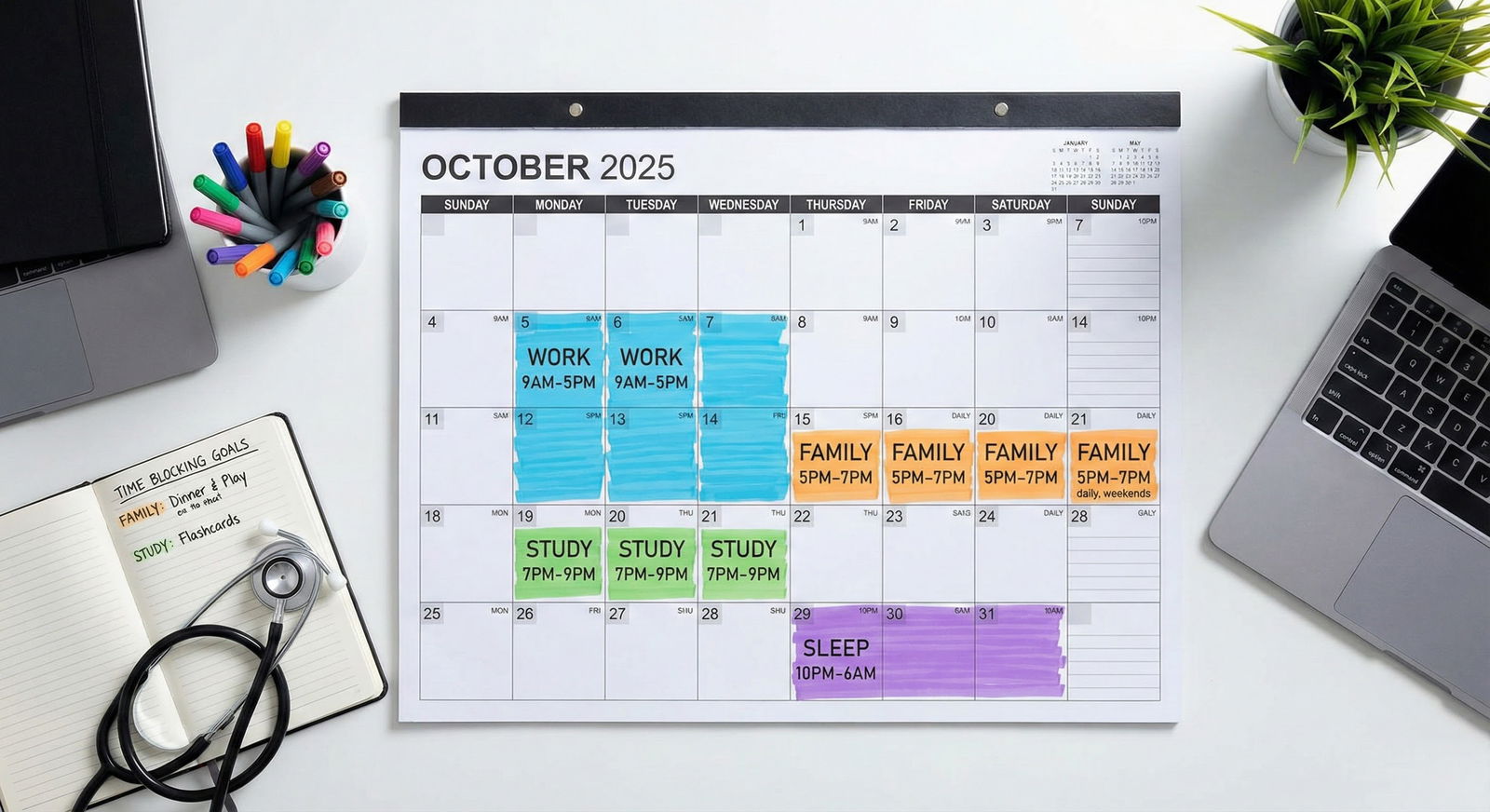

For the next 2–4 weeks:

Track your duty hours honestly

Write down actual arrival/departure times. Not what you log. What you live.Note specific malignant events

Date, person involved, what happened, any witnesses. Short bullet. That’s it.Record your mental health patterns

0–10 scale each day for mood and anxiety. Quick notes like “couldn’t sleep,” “panic on call,” “okay day, attending actually taught.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | 3 |

| Day 2 | 4 |

| Day 3 | 2 |

| Day 4 | 2 |

| Day 5 | 5 |

| Day 6 | 3 |

| Day 7 | 4 |

| Day 8 | 2 |

| Day 9 | 1 |

| Day 10 | 3 |

| Day 11 | 4 |

| Day 12 | 2 |

| Day 13 | 3 |

| Day 14 | 2 |

Why this matters:

When you later talk to a mentor, ombuds, or even another program director, “My program is toxic” is weak. But:

- “Four weeks in a row over 90 hours; post-call days regularly violated”

- “Attending X yelled at me in front of the team: ‘You are an embarrassment to this institution’ on [date]”

- “Reported duty hours accurately and was called in by chief who told me to ‘fix’ my logging or I’d be labeled not a team player”

That’s credible. That’s actionable.

And for you personally, patterns will clarify: Are there any rotations, services, or teams that are tolerable or even decent? Or is it systemic across everything?

Step 4: Quietly Build Your Support and Advisory Team

If you try to decide in a vacuum, you’ll either stay forever or blow everything up in one bad week.

You need 3 types of people:

Someone inside your institution but outside the PD/chief structure

- GME office

- Resident ombudsperson

- ACGME Designated Institutional Official (DIO)

- A trusted attending not deeply enmeshed in program politics

Someone outside your institution but inside your specialty

- Former faculty from med school

- Trusted attending from a rotation at another site

- An alumni from your med school now practicing your specialty elsewhere

Someone who cares about you more than your CV

- Partner, sibling, friend, therapist

- Someone who will ask, “What happens to you if you stay another year here?”

You talk to each group differently.

With internal people, you’re focused on:

- Safety

- ACGME compliance

- Exploring whether things can realistically change

With external people, you’re focused on:

- How your current program’s reputation actually looks

- How transferring is viewed in your specialty

- What concrete paths out might exist

With personal people, you’re focused on:

- Your health

- Your relationships

- Your non-negotiables as a human being

Step 5: Evaluate Three Options: Stay, Transfer, or Exit

Let’s be brutal: you are choosing between three unpleasant paths.

| Option | Main Upside | Main Downside |

|---|---|---|

| Stay | Stability, no gap | Ongoing toxicity, health risk |

| Transfer | Better fit possible | Logistical risk, no guarantees |

| Exit | Immediate relief | Career reset, identity shock |

We’ll focus on the stay vs transfer decision, but don’t pretend option 3 doesn’t exist. It does. And for a small subset, it’s the right answer.

Option A: Staying and trying to survive

Staying makes sense if:

- The program is hard and poorly run but not maliciously punitive

- You see actual movement when issues are raised (not just lip service)

- Your mental health is fragile but responding to treatment

- You have at least 2–3 attendings or faculty who are clearly in your corner

- There’s a realistic “light at the end of the tunnel” (better senior years, electives, offsite rotations)

Staying does not make sense if:

- You fear retaliation every time you speak honestly

- You’re already at a breaking point mentally or physically

- You’re starting to compromise patient safety to keep up

- You’ve been told, directly or indirectly, that you’re “a problem” for raising valid concerns

“Just finish” sounds tough and stoic. It can also be cowardly. An excuse to avoid a hard decision.

Option B: Transferring programs

You do not transfer out of mild discomfort. You transfer when:

- The environment is truly unsafe or abusive

- You have clear, documented patterns of toxicity

- Your attempts to address problems internally have gone nowhere or backfired

- Your mental health and basic functioning are deteriorating despite effort and support

Here’s the ugly truth: transferring is work. It can mean:

- Extra interviews during an already brutal schedule

- Explaining yourself without trashing your current program

- Risk that you don’t land anywhere and have to re-enter Match or step away

This is why you don’t impulsively resign one bad week in January. You plan an exit while still functional enough to do it.

Step 6: How to Assess Whether Transferring Is Realistically Possible

Different specialties have different ecosystems. Transferring from IM is not the same as transferring from neurosurgery.

Track these factors:

Specialty competitiveness

Derm/rads/optho: very few spots, transfers rare.

IM/FM/Peds/Psych: more fluid, transfers more common.

Surgery: possible, but often requires networking and a clean reputation.Your performance record

Even in a malignant program, are your evaluations mostly solid? Any professionalism red flags? Failed rotations?

Program directors will care more about that than your duty hours rant.Your exam status

Step 3 done or not? Specialty in-training exam (ITE) scores?

Like it or not, these numbers will be used as shorthand for “low-risk recruit.”Timing in training

Transfers after PGY-1 or early PGY-2 are more common. After that, it’s trickier but not impossible.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| PGY-1 | 70 |

| PGY-2 | 50 |

| PGY-3 | 30 |

| PGY-4+ | 15 |

Then, you have to quietly find out:

- Are there open PGY-2 spots in your specialty?

- Does your specialty’s national organization have a job board or listserv for open positions?

- Any PDs or faculty from med school willing to make calls on your behalf?

If the answers are yes, transferring is an actual option, not a fantasy.

Step 7: The Conversation You Dread: Talking to Your PD (Or Not)

Eventually, if you pursue a transfer, your current PD will likely find out. The question is: when and how exposed you want to be.

General rules:

If your PD is marginally decent and not known to retaliate, consider a careful conversation:

“I’m struggling significantly here for [specific reasons], and I’m exploring whether another environment might be a better fit for me long-term. I want to be transparent and professional.”If your PD is petty, vindictive, or has openly punished residents for speaking up, you do not start with them. You start with:

- GME / DIO

- An external mentor

- Possibly quietly exploring openings before you even hint at anything locally

Your PD will almost certainly be asked for a letter if you transfer. You cannot fully control what they say, but you can shape the narrative:

- Own your part: “I struggled with X early on, since then I’ve done Y to improve.”

- Emphasize professionalism and patient care.

- Avoid character assassination of the program; focus on fit and well-being.

I’ve seen malignant PDs sabotage residents, yes. I’ve also seen residents catastrophize this more than necessary. Many PDs, even in rough programs, are relieved when a clearly unhappy resident finds a better aligned fit.

Step 8: Ethics: Are You “Abandoning” Patients or Co-residents?

This guilt keeps a lot of people stuck.

Let’s be blunt:

You are not the solution to a broken residency culture.

Staying in a malignant program as a martyr does not fix it. It just hurts you. Maybe permanently.

Ethically, your obligations are:

- Provide safe care while you’re there

- Report serious violations honestly (duty hours, abuse, safety issues)

- Don’t lie or falsify documentation or evals to protect the institution

You do not have an ethical obligation to sacrifice your mental health or future to prove how tough you are. That’s not professionalism. That’s self-harm wrapped in a white coat.

If leaving means one fewer resident for your co-interns? That’s on the institution that created an unsafe environment, not on you.

Step 9: A Simple Decision Framework: 4 Questions

By this point, you should have more clarity. Use these four brutally direct questions:

If nothing meaningful changed in this program over the next 12 months, what would happen to my mental and physical health?

Be specific. Hospitalization? Divorce? Burnout so severe you quit medicine?If I stay solely out of fear or inertia, what will I regret more in five years: staying or leaving?

Picture two futures: one where you stuck it out, one where you transferred. Which version of you looks healthier, more functional, less bitter?If a close friend described my exact situation, what would I advise them to do?

Your advice to others is often more rational than your self-talk.Do I have enough internal and external support to attempt a transfer while staying safe where I am?

If the answer is no, your next step is not “decide.” It’s “build support.”

Once you answer these honestly, the decision usually stops feeling 50/50.

Step 10: If You Decide to Transfer—Tactical Next Steps

Keep it practical:

Clean up anything you can control locally:

- Be on time

- Document thoroughly

- Avoid gossip and open complaining; assume word gets back

Quietly update your CV:

- Highlight any quality improvement, teaching, or leadership you’ve managed despite the chaos

- Have a clean, concise explanation for any gaps or issues

Start targeted outreach:

- Contact med school mentors with a tight, factual summary (no rants)

- Ask directly: “Do you know of any programs that might be a better fit, or any open PGY-2 positions?”

Protect your mental health aggressively during this period:

- Non-negotiable therapy or peer support

- Sleep hygiene even if you have to disappoint people socially

- Absolutely no self-medicating with alcohol or substances—this is where careers quietly die

If/when you interview:

- Do not trash your current program in detail

- Use language like “mismatch,” “culture not aligned with my values,” “seeking a more supportive educational environment”

- Be concrete about what you’re looking for, not just what you’re running from

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Realize program may be malignant |

| Step 2 | Document reality for 2-4 weeks |

| Step 3 | Assess mental health and specialty fit |

| Step 4 | Consider specialty change or exit |

| Step 5 | Build support team |

| Step 6 | Evaluate stay vs transfer options |

| Step 7 | Stay with safeguards and support |

| Step 8 | Plan and pursue transfer |

| Step 9 | Still want this specialty? |

| Step 10 | Staying safe and sustainable? |

If You Decide to Stay—Make It a Conscious, Conditional Choice

Staying can be reasonable. But don’t just “drift” into it.

Set conditions for yourself:

- “If my hours remain above X for the next Y months, I will reopen the transfer discussion.”

- “If my mood or anxiety scores stay at [this] level after consistent therapy/meds, I will not renew my contract here.”

- “If I experience direct retaliation for honest reporting again, I will escalate outside the institution.”

And tell someone your conditions. Out loud. So you can’t gaslight yourself later into enduring anything.

Then, optimize what you can:

- Seek out the best rotations/mentors in the system and cling to them

- Carve out some part of your life that is off-limits to residency (a hobby, a relationship, therapy, something that is yours)

- Keep documenting safety and abuse issues; future you might still need that paper trail

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Will transferring ruin my career or make me look weak?

No, not by default. PDs care about patterns. If your narrative is: “I was in a chronically unsafe, unsupportive environment, I handled it professionally, and I’m seeking a place where I can train safely and grow,” many will respect that. What hurts you is appearing chaotic, bad-mouthing everyone, or having professionalism red flags. A clean, honest, focused explanation is rarely a dealbreaker—especially in non-ultra-competitive fields.

2. What if there are no open spots and I’m trapped?

You’re not completely trapped, but your options narrow. If no transfer spots are realistic right now, your next moves are: aggressively stabilizing your mental health, maximizing external rotations/electives for networking, and setting a concrete timeline (e.g., finish this year, then reassess match/re-entry or a different path in medicine). In a few cases, taking a leave of absence to regroup and plan has saved people from either a breakdown or a permanent exit from medicine.

3. How do I know if it’s “bad enough” to justify leaving?

Ask yourself three things: (1) Is my safety or my patients’ safety regularly compromised by structural issues I can’t fix? (2) Is my mental or physical health clearly deteriorating despite using reasonable supports? (3) Do I see any credible path to improvement within the program over the next 6–12 months? If you’re answering yes, yes, and no—then it’s “bad enough.” At that point, leaving isn’t overreacting; it’s basic self-preservation.

Key points:

You are not obligated to sacrifice your health to survive a malignant program. Decide with data, not just emotion: document what’s happening, assess your mental state and specialty fit, and build a support team. If you stay, do it as a conscious, conditional choice; if you transfer, do it strategically and professionally—your future self will thank you.