It’s 11:47 p.m. Your ERAS list is open. Your “dream specialty” column looks clean and satisfying. Then there’s that ugly second column: backups. You type in “Internal Medicine” or “Family Medicine” or “Pediatrics,” stare at it for 10 seconds, then delete it. Because the thought running through your head is basically:

“What if I match there and hate my life for three years?”

You can almost see Future You. Crying in call room bathrooms. Dreading every shift. Regretting that one rank list you submitted at 2 a.m. because everyone told you to have a backup.

Let’s be honest: this isn’t some abstract fear. This is the “I will ruin my entire career if I pick wrong” voice. And it’s loud.

Let me walk through this with you like someone who has seen people match their “backup,” freak out, and still end up more okay than they thought. And also seen people pick terrible backups because of fear and bad advice.

Step 1: Separate Three Different Fears You’re Mushing Together

You’re probably not scared of “backup specialties” in general. You’re scared of a mash-up of three different things:

- “What if I’m miserable for all of residency?”

- “What if I’m stuck forever in a field I only kind of like?”

- “What if this proves I wasn’t good enough for my dream specialty?”

Those are different problems. And each has a different reality check.

1. “What if I’m miserable for all of residency?”

Residency is hard no matter what. Ask anyone. The “I hate my life” moments show up in ortho, in psych, in FM, in derm. Misery is a mix of:

- Program culture

- Schedule and call structure

- How supported (or abused) you feel

- Your life stuff (health, relationships, money)

Specialty matters, obviously. But the program matters a lot more than anxious brains want to admit. I’ve seen IM residents at chill, supportive community programs who are objectively happier than some competitive-specialty residents who matched “dream field” at malignant places.

So the actual question isn’t just “Will I hate this specialty?” It’s “Can I find enough programs in this specialty where my day-to-day would be tolerable-to-decent for 3 years?”

That’s a much less catastrophic question.

2. “What if I’m stuck forever in a field I only kind of like?”

You know what’s funny? A lot of people end up sub-specializing or shifting somehow anyway. Cards, GI, palliative, sports, pain, hospitalist, outpatient-only, academic, admin, informatics. Most “broad” specialties are really families of jobs.

If your backup is something like IM, FM, Peds, Psych, EM, you’re not assigning yourself one exact job for the rest of your life. You’re giving yourself a launch platform with lots of exits.

Is it true that some paths are narrower? Yeah. If your backup is something hyper-specific with almost no fellowships, then that feels more “trapped.” But most common backups are flexible by design.

3. “What if this proves I wasn’t good enough?”

This one is about shame, not specialty.

You’re imagining PDs, faculty, maybe even your classmates thinking, “Oh, they couldn’t hack derm/ortho/rads, so they settled.” You’re imagining feeling like a failure every single time you introduce yourself: “Hi, I’m Dr. Not-Good-Enough.”

And yet. Every year I watch people match “backups,” go through a 3–6 month ego death, and then slowly transition to: “Oh wait, I kind of…like this?” And by PGY-2, they’re genuinely invested in their field, and no one cares what they originally applied to.

Reality check: the self-judgment is way harsher than what anyone else will carry around about you.

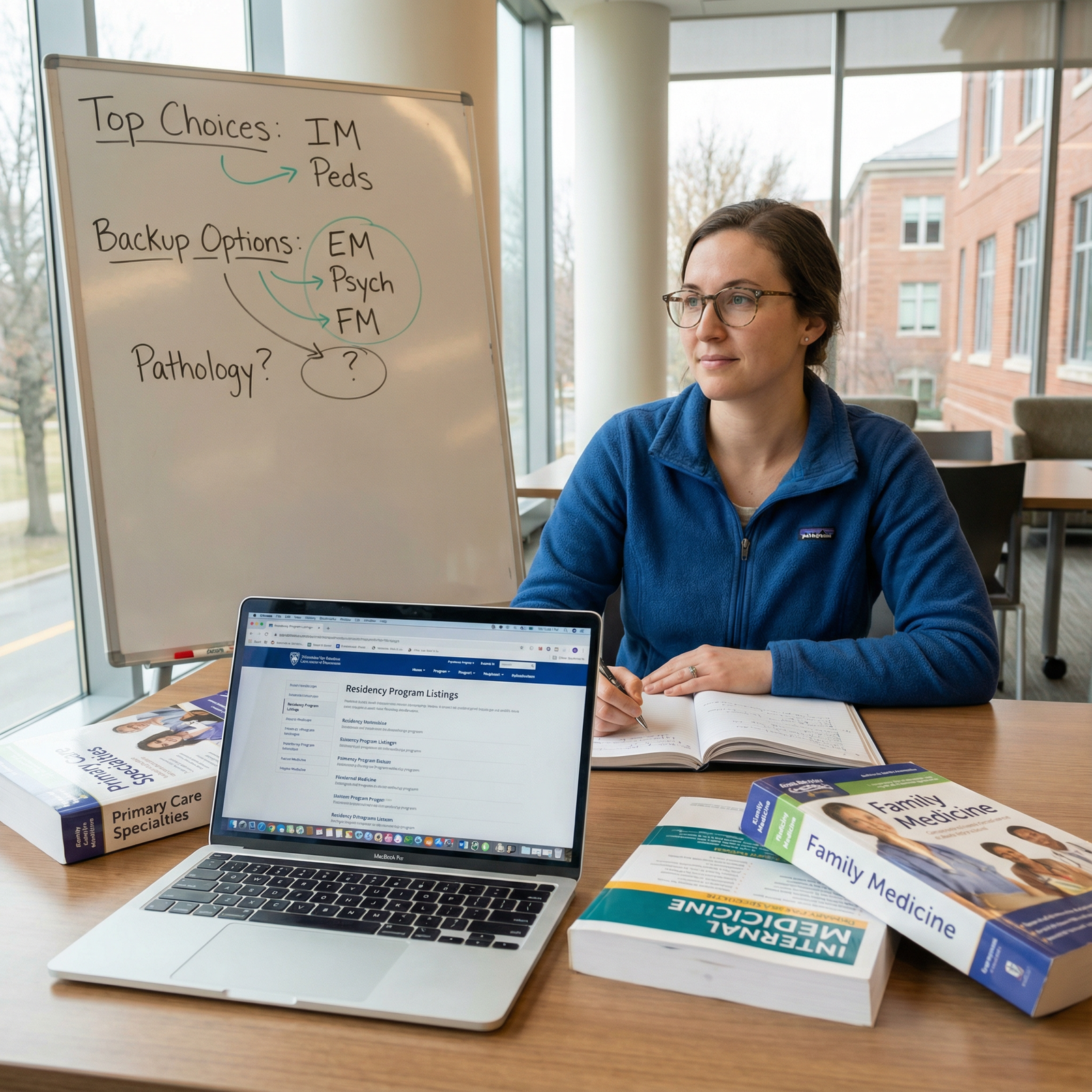

Step 2: Do a Brutal, Honest Reality Scan of Your “Dream” vs “Backup”

You can’t reality-check your fear if your view of both specialties is just: “Dream = perfect. Backup = living hell.”

Let’s unpack. You need to answer four questions for any potential backup specialty:

- What parts of the day would I actually be doing?

- What parts of residency in this field would I absolutely hate?

- What specific job at the end of this would I be aiming for?

- Is the worst-case day in this specialty truly unlivable for me?

This needs to be concrete, not vibes.

Here’s a simple way to line things up:

| Aspect | Dream Specialty | Backup Specialty |

|---|---|---|

| Residency Length | 5 yrs | 3 yrs |

| Nights/Weekends | High | Moderate |

| Procedure Intensity | High | Low |

| Outpatient vs Inpt | Mostly Inpt | Mixed |

| Fellowship Options | Few | Many |

Those are sample values, obviously. The point is: get specific.

Maybe your “dream” is surg, your backup is IM. Worst-case IM day = notes, rounding, consults, some scut, some exhausted families. Worst-case surg day = nonstop OR, pre-round at 4:30 a.m., 28-hour call, getting yelled at over suctioning.

You don’t have to suddenly “like” the backup specialty. Just be honest:

“Could I keep my sanity doing the worst 20% of days in this backup field if I knew it led to a job I could tolerate or even like?”

If the answer is a hard “absolutely not, I would wither,” then that’s a bad backup. Panic deleted or not, you listened to something important.

Step 3: Ask the Right People the Right Questions (Not the Ones You’re Asking Now)

When you talk to residents, you’re probably asking the wrong thing. You ask: “Do you like your specialty?” They give some generic answer: “Yeah, I really enjoy it overall.”

That tells you nothing.

Ask this instead:

- “What are the parts of your DAY you dread?”

- “What do attendings in this field complain about at 2 a.m. when they’re off guard?”

- “If your kid wanted to do this, what would you warn them about first?”

- “What kind of personality seems miserable here?”

- “What do people who regret this choice usually say?”

You’re trying to find deal-breakers, not confirmation.

Also, ask people who left or almost left. The PGY-2 who transferred from Gen Surg to Anesthesia. The IM resident who thought about switching to Psych. Their “almost quit” stories are extremely useful.

Step 4: Use One Nasty But Powerful Thought Experiment

This is harsh, but it works.

Imagine it’s March. You didn’t match your dream specialty. You SOAP (or you applied initially with a backup). The only good backup specialty you listed picks you up.

You match into it.

And now you are not allowed to transfer. No magic. No do-overs.

The question isn’t: “Would I be ecstatic?” Obviously not. The real question:

“After the grief and ego-bruising, could I see myself learning to build a decent life here? Or does that scenario send me into full-body panic?”

If just picturing yourself as that resident makes you feel a sort of heavy, suffocating dread, listen to that. Your brain might be telling you: this is not just fear of ‘not perfect,’ this is ‘this is wrong for me.’

If instead you feel sad, disappointed, maybe a little nauseous, but you can also see some “okay maybe if I did this fellowship / this type of job / this practice setup…” then that fear is probably louder than it deserves to be.

Step 5: Actually Look at Future You, Not Just Residency You

Huge mistake anxious people make: evaluating everything through the lens of PGY-1–PGY-3.

Residency is temporary. The job is much longer.

So, yeah, let’s be a little cold and strategic. Say your backup is IM. You hate general wards, but you like thinking, talking to patients, and not cutting things open.

Could you be:

- Hospitalist with 7-on/7-off?

- Outpatient-only with 4-day weeks?

- Palliative care where the focus is communication and symptom control?

- Cards, GI, heme/onc, ID, nephro if you can tolerate IM residency for a fellowship ticket?

You’re not signing up for “IM wards Q4 call for eternity.” You’re signing up for “3 years of IM plus reasonable odds of carving out a post-residency niche you can stand.”

Residents massively underestimate how different attending life can look.

| Category | Scut / Admin | Direct Patient Care | Education / Autonomy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residency | 40 | 40 | 20 |

| Attending | 20 | 55 | 25 |

Is this universal? No. But the pattern is real enough to factor into your fear calculation.

Step 6: Red-Flag vs Yellow-Flag Feelings About a Backup

Let me draw a line between “this is uncomfortable backup anxiety” and “this is a truly bad fit.”

Yellow-flag / Anxious but Possibly Okay Signs:

- You’re mostly worried about prestige and what people think.

- You’re sad about giving up specific procedures or tech, but you don’t hate the actual patients in the backup field.

- You could picture one or two types of jobs in that specialty that you’d actually be fine doing.

- Your main fear is, “What if I never love it as much as my dream?”

Red-flag / Please Don’t Use This as a Backup Signs:

- You strongly dislike the core patient population (e.g., you actively dread kids, but you’re listing Peds “just in case”).

- You’ve done rotations in it and felt drained almost every single day.

- The worst days in that field feel like your personal nightmare, not just “hard doctoring.”

- When you shadowed or rotated, the attendings’ “bad days” looked like your hell.

If you’re seeing red flags, that specialty should not be on your rank list as “backup.” Matching there is not a win, it’s a slow-burn disaster.

Step 7: How to Build a Backup Strategy That Doesn’t Feel Like Self-Betrayal

If you decide you do want a backup, here’s how to make it feel less like surrender.

Pick a backup that:

- Has at least one core thing you actually enjoy (patient population, type of thinking, procedures, lifestyle, something).

- Has real-world jobs you’ve seen that you wouldn’t mind having.

- Offers multiple post-residency paths.

- You’ve experienced beyond one crappy rotation.

Then, when you rank:

You’re not ranking “Fields I Love vs Fields I Despise.” You’re ranking “Best versions of my future life vs still acceptable versions of my future life.”

That’s a huge psychological shift.

And yeah, there’s risk either way. If you don’t list a backup at all, worst-case is not matching. If you do list one, worst-case is matching somewhere that becomes a three-year grind.

You’re choosing which risk you’d rather carry. No option is perfectly safe. That’s not your fault; that’s the system.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Choose Dream Specialty |

| Step 2 | Identify Possible Backup |

| Step 3 | Apply Without Backup |

| Step 4 | Apply and Rank Backup |

| Step 5 | Do Not Use That Backup |

| Step 6 | Consider Different Backup or No Backup |

| Step 7 | Competitive Risk High |

| Step 8 | Backup Worst Case Tolerable |

Step 8: Talk Honestly With Yourself About Regret

Last thing: future regret.

If you don’t match at all because you refused to list any backup, will you be able to say, “I’d do it the same way again; that was worth the risk”?

Some people genuinely can. They’d rather SOAP, try again, or switch careers than do something they know isn’t them. That’s valid.

Others, if they’re honest, would be devastated and second-guess themselves forever: “Why didn’t I list IM/Peds/FM when I knew I could have been okay there?”

You have to decide which regret you’d rather risk:

- Regret A: “I matched backup and needed time to grow into liking it.”

- Regret B: “I didn’t match when I could’ve had a decent, if not perfect, path.”

There isn’t a morally correct answer here. There’s just the one that you, with your actual nervous system and life circumstances, can live with.

FAQ (Exactly 6 Questions)

1. What if I genuinely like only one specialty and everything else feels awful?

Then you need to be brutally honest about competitiveness. If your scores, letters, and application are significantly below typical matched applicants, going “all-or-nothing” is a conscious gamble, not a tragedy if it doesn’t work. If you can’t find any backup whose worst days you can tolerate, forcing a backup is just self-betrayal. In that case, either accept the risk of not matching or consider a slightly adjacent, less competitive field that still overlaps your core interests.

2. How many backups should I apply to if I’m scared of being “pulled” into them?

You don’t need five backups. One realistic backup field is often enough, applied to a sane number of programs. You can still rank all your dream programs above every backup program. The presence of a backup doesn’t magically “steal” you away; the algorithm only gives you your backup if no dream program ranks you high enough. The real decision is whether you’re okay with that safety net existing at all.

3. What if I match my backup and want to switch later?

Transfers do happen, but they’re not guaranteed and shouldn’t be the foundation of your plan. Spots need to exist, PDs need to support you, and timing has to work. Think of switching as a possible bonus, not a rescue boat. If you must switch to avoid misery, that’s a sign your “backup” wasn’t actually acceptable for you in the first place.

4. My advisor says I “need” a backup. Are they wrong?

They’re not automatically wrong, but they’re looking at population-level risk, not your individual tolerance. Advisors hate unmatched statistics; you hate the idea of being trapped in the wrong field. Both are valid concerns. Listen to their data, then weigh it against your own red-flag feelings. If an advisor is pushing a backup specialty that you’ve consistently hated on rotations, it’s okay to say no.

5. How do I tell if I’m just scared of change vs truly hating a specialty?

Look at your actual experience, not your imagined version. On rotations or shadowing: did you ever have a day in that specialty that went by quickly, where you didn’t resent being there? Did any parts of it feel “natural” to you, even if you weren’t excited? If yes, that’s fear and loss talking more than hatred. If every day felt like you were pretending to be someone else, that’s closer to genuine misfit.

6. Can I still have a good career if I end up in my backup specialty?

Yes. Absolutely yes. Every year, people match their backup, mourn their Plan A for a while, then quietly build genuinely satisfying careers—sometimes better in lifestyle or flexibility than their original dream. The path might look different than you imagined, but that doesn’t make it second-rate. Your career is long; how much you grow into it matters more than the label of “backup” or “dream.”

If you remember nothing else:

- A backup shouldn’t be a field you hate—only one whose worst days you can still survive.

- Program and job type matter almost as much as specialty.

- You’re not choosing “bliss vs doom”; you’re choosing between different kinds of risk.