The culture of residency still quietly tells you to “push through” chronic pain. That culture is wrong—and it is breaking people.

Let me be blunt: if you are a resident with chronic pain and you are not thinking strategically about ergonomic and duty‑hour modifications, you are gambling with your career longevity. Programs, on the other hand, are gambling with accreditation and federal law when they pretend accommodations are “optional favors.”

This is not about being “soft.” It is about precision-engineering your work environment so you can actually do the job for 3–7 years without destroying your spine, joints, or nervous system.

I am going to walk through what actually works: specific ergonomic changes, realistic scheduling modifications, how to frame accommodations under the ADA, and how to balance safety, education, and your own body in a system that is not built for disabled trainees.

1. The Reality of Chronic Pain in Residency

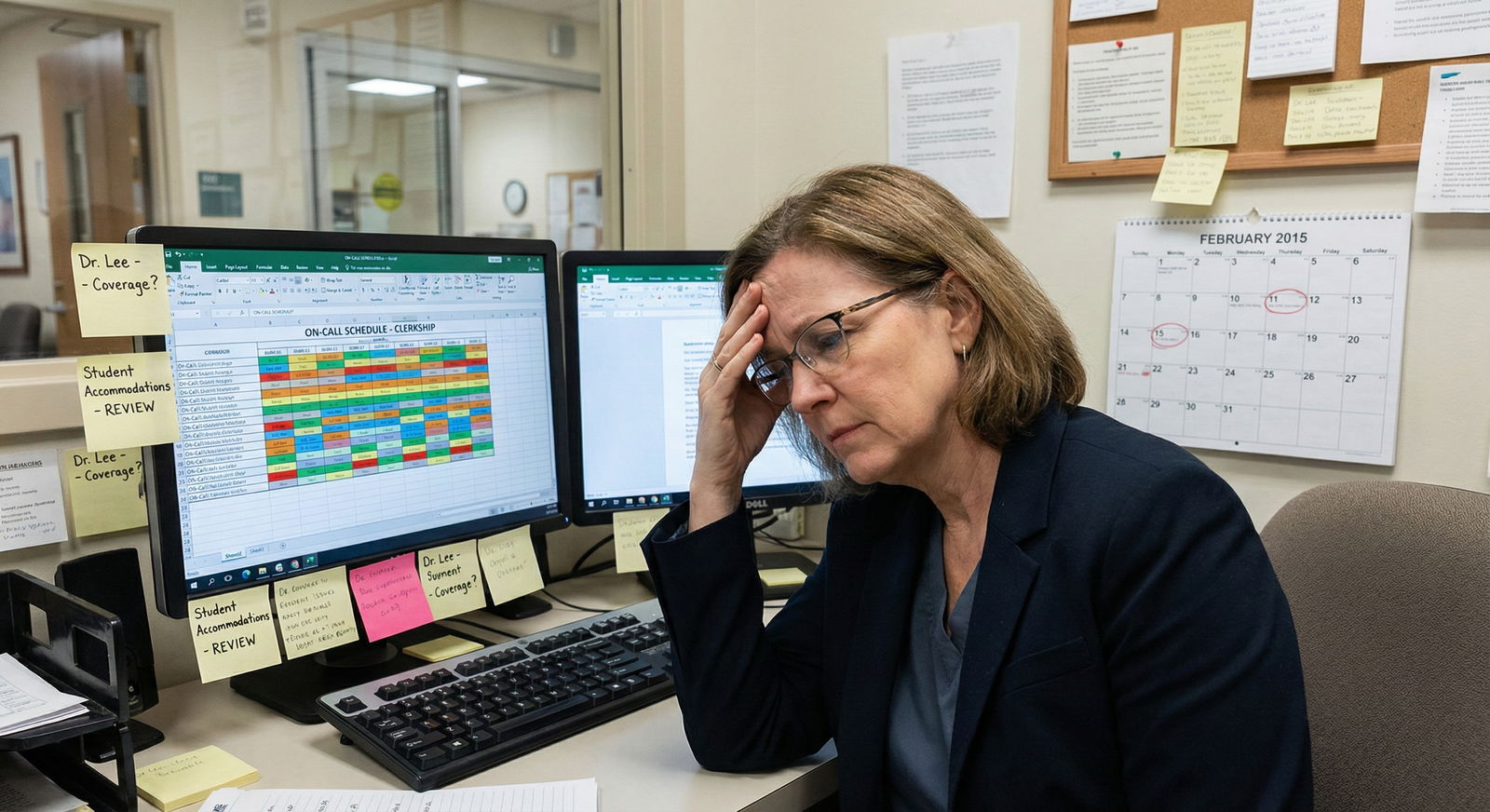

You already know the basics: long hours, standing procedures, bad chairs, pager going off just as you sit down. But chronic pain changes the entire calculus.

The typical pattern I see:

- MS4 with a manageable back/neck/shoulder issue or migraine disorder.

- Intern year ramps up: more nights, more standing, more EMR time.

- By PGY‑2, pain is daily. Sleep is trash, PT gets canceled for “patient care needs,” and the resident is living on NSAIDs, topical stuff, and willpower.

- By PGY‑3, they are either:

- quietly disabled and hiding it, or

- in crisis: needing leave, dropping procedures, or contemplating quitting.

What makes this ugly is the mismatch between reality and expectations. The system assumes:

- Infinite standing tolerance for OR/rounds.

- Instant transitions from clinic to inpatient to nights with no recovery.

- Workstations set for average-height, non-disabled bodies.

- That “if it was really bad, the resident would say something.”

They often do not. Because they are afraid of being labeled weak, unhirable, “not a team player,” or—my personal favorite coded phrase—“not robust enough for our specialty.”

The law does not care about those narratives. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 are very clear: chronic pain conditions that substantially limit major life activities (walking, standing, lifting, working, sleeping) can qualify as disabilities, and residency programs are covered entities.

The trick is translating that into actual ergonomic and duty‑hour changes that work on the ground.

2. Framework: What Counts as a “Reasonable” Modification?

Before we get tactical, you need a clean mental model of what you can legitimately ask for.

Broadly, you are working with three overlapping domains:

- Ergonomic modifications

- Schedule/duty‑hour modifications

- Task or rotation restructuring

And you are balancing three constraints:

- Your essential job functions as a resident physician.

- Patient safety and team function.

- Program resources and “undue hardship.”

Most programs quietly overestimate what “essential” means and underestimate how many creative modifications are legally reasonable. You do not have to accept their first answer.

For chronic pain, accommodations commonly revolve around:

- Limiting prolonged standing / walking.

- Enabling frequent micro‑breaks.

- Reducing repetitive strain and awkward postures.

- Controlling sleep deprivation and circadian chaos (especially migraine, neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia).

- Ensuring access to treatment (PT, pain clinics, injections, infusions).

Keep that list in your head when we talk specifics.

3. Ergonomic Modifications: What Actually Moves the Needle

Most hospital “ergonomics” lip service is laughable. A poster about lifting with your legs, a random lumbar pillow in the call room, and they call it a day. That is not going to cut it if you have chronic pain.

I will break this down by environment: workrooms/EMR, clinic, OR/procedural, wards/rounding.

3.1 Workrooms and EMR: Where You Quietly Destroy Your Neck and Back

You will log thousands of hours at computers. Done poorly, this alone can keep your pain at a 7/10 baseline.

Specific accommodations that are reasonable and useful:

Adjustable sit‑stand desk access

Not for vanity. For survival. Standing for 5–10 minutes every 45–60 minutes can keep axial pain from ramping up. The key is predictability.Reasonable requests:

- “Assignment of at least one height‑adjustable workstation per workroom that I am explicitly permitted to use as primary when present.”

- “Permission to alternate sitting and standing while charting, pre‑rounding, calling consults, and signing orders.”

External keyboard, mouse, and monitor

Laptop-only work is a neck and shoulder disaster.Ask for:

- External ergonomic keyboard (split or low-profile if you have wrist issues).

- Vertical mouse or trackball if you have wrist/forearm pain.

- External monitor at eye level to reduce cervical flexion.

Chair with real adjustability

Not the broken rolling stool from 1998 with one missing wheel.You want:

- Height adjustability so hips are roughly at or slightly above knees.

- Good lumbar support or a separate lumbar cushion.

- Stable base and armrests if shoulder girdle is a problem.

Defined “no charting from bed/couch” rule for yourself

Use accommodations to make proper workstation use easy. Stop doing 2 hours of notes from a bunk bed on a laptop.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Laptop on bed | 100 |

| Fixed low desk | 80 |

| Standard desk + monitor | 40 |

| Sit-stand setup | 25 |

3.2 Clinic: Standing, Exam Tables, and Exam Rooms That Hate You

Clinic looks harmless until you realize you are standing for most of the day in cramped rooms.

Common, targeted modifications:

Stool in every exam room you use

You should be able to sit for parts of the history, counseling, and even portions of the exam if it does not compromise care.That might look like:

- Sitting for history and patient education.

- Standing briefly for lung/heart/abdominal exam.

- Sitting again while documenting and ordering.

Adjusted template to allow micro‑breaks

Example:- Insert a 10‑minute “admin block” after every 3–4 patients to stretch, hydrate, and do quick documentation sitting properly instead of “just catching up at the end” when pain is at max.

Room assignment considerations

Avoid being assigned the farthest room from workroom or one that requires repeated long walks.Ask for:

- “Preferential assignment to clinic rooms within shortest walking distance from workroom when scheduling allows.”

3.3 OR / Procedural Suites: The Hardest Ergonomic Environment

Here is where people get stuck. They assume: “If I cannot stand for a 6‑hour case, I cannot be a surgeon/anesthesiologist/OB‑GYN.” That is not fully accurate.

Can you be a neurosurgeon who cannot stand more than 30 minutes at a time? Realistically, probably not. But can you be an anesthesiologist with a sit‑stand stool and thoughtful case selection? Often yes.

Concrete ergonomic changes that are realistic:

Adjustable height stools for cases

Serious programs already have these; they just are not used consistently.For chronic pain:

- Request a procedure stool with proper back support.

- Use it whenever possible during parts of the case that do not strictly require standing (obviously not during emergent airway, but for long maintenance periods, line placement, etc.).

Step platforms and table height negotiation

Standing with shoulders abducted above 90 degrees for hours is a recipe for cervical and thoracic pain.You want:

- To be able to request table height adjustment to neutral elbow height when feasible.

- Step platforms adjusted so you are not in extreme reach or lumbar hyperextension.

Role distribution in long cases

For a 6–8 hour case:- You can ask for shared primary operator time, timed relief breaks, or rotation to assisting position for parts of the case that are more static.

Programs hate the word “accommodation” in the OR because they imagine chaos. In reality, most of this is just structured planning.

3.4 Wards and Rounding: The Bandaid Fix for Terrible Design

Walking 15–20k steps on hard floors with no pacing control is brutal on backs, hips, and lower extremity joints.

Modifications that work:

Sitting rounds or mixed‑model rounds

Many academic services already do this.You can float:

- Family-centered rounds where patient interaction is in room, discussion at a sitting workstation just outside.

- Use of conference rooms for part of teaching/plan review instead of entire rounds on your feet.

Reasonable limits on “pointless” walking

For instance:- Consolidating trips to radiology, pharmacy, and other floors when possible.

- Using phone consults/telemedicine when clinically appropriate instead of physically trailing consultants.

Permission to sit during sign-out, team huddles, and teaching

Sounds obvious. I have seen PGY‑1s with obvious pain stand through a 45‑minute chalk talk because everyone else is standing.You want an explicit, normalized pattern: you sit; it is not a big deal.

4. Duty‑Hour and Schedule Modifications That Are Actually Defensible

Let me be direct: residency is not a 9–5 job, and no accommodation will turn it into one. If your expectation is “I want a 40‑hour week,” you are going to be disappointed and your request will likely be denied as unreasonable.

But there is a huge range between “standard abusive schedule” and “impossible burden.” Chronic pain—especially when tied to sleep disruption, neuropathic flares, or systemic inflammatory conditions—often justifies targeted schedule changes.

Think in categories:

- Total hours per week

- Consecutive hours per shift

- Night float and circadian disruption

- Recovery time between shifts

- Predictability for medical care

4.1 Weekly Hour Targets: From Theoretical Max to Functional Cap

ACGME caps are 80 hours averaged over 4 weeks. That is a ceiling, not a requirement. Many residents sit between 60–75 hours.

For chronic pain, a realistic target is often 55–65 hours, with careful structuring of the heaviest services.

Reasonable requests might include:

- “Avoid regularly scheduled assignments that would exceed 70 hours per week; cap my scheduled clinical time at 60–65 hours when possible, with prioritization of rotation selection to remain within this band.”

This is more likely to fly than “I want 45 hours.” Frame it as: still meeting educational requirements, just not consistently pegged to the extremes.

| Schedule Type | Hours/Week | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy ICU month | 75–80 | Standard in many programs |

| Busy ward month | 65–72 | Frequent late stay |

| Outpatient month | 45–55 | More predictable |

| Modified for pain | 55–65 | Reduced extremes, more clinic |

4.2 Shift Length and “Marathon” Days

For some pain disorders, the difference between 14 and 28 continuous hours is the difference between functional and non-functional for days.

You can reasonably explore:

- No 24‑hour+ in‑house calls

Instead:- Night float systems.

- 16-hour maximum shifts.

- Or senior back‑up with earlier handoff.

This is not trivial because it affects coverage models, but it has precedent. Residents who are pregnant, have seizure disorders, or are post‑surgery often receive similar modifications.

- Caps on back‑to‑back long shifts

Example request:- “Limit consecutive days exceeding 12 clinical hours to no more than 3 at a time, followed by at least one day with ≤8 scheduled hours.”

4.3 Nights, Circadian Disruption, and Pain

Chronic pain loves sleep disruption. Night float can turn a manageable pain disorder into a disaster.

Reasonable modifications:

Reduced number of night rotations across residency

Not zero (unless your condition is extreme), but fewer than peers.Example:

- If categorical residents do 3 months of night float across 3 years, you might do 1–2 with more emphasis on day rotations.

Clustering nights with adequate recovery

It is often better to do:- One or two blocks of nights with well-defined pre/post recovery days

than - Constant flipping between days and random single nights.

- One or two blocks of nights with well-defined pre/post recovery days

Protection from “flip-flop” scheduling

For example:- Avoid schedule patterns like 2 day shifts, 1 night, back to days.

4.4 Protected Time for Treatment

This is non-negotiable if you want any long-term improvement.

You may need regular:

- PT/OT

- Pain clinic injections or infusions

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for pain

- Acupuncture / other modalities

Reasonable, specific asks:

- “Protected half‑day every 2–4 weeks for medical appointments related to my documented condition, not counted as vacation, scheduled with at least 4 weeks’ notice.”

Programs already do this with residents on dialysis, chemo, or pregnancy-related care. Chronic pain should not be treated as lesser.

5. How to Actually Request These Accommodations

Process matters. If you throw out a vague, emotional plea, you will get a vague, emotional response. You need to be clinical about this.

5.1 Build a Functional Limitations List

Not “I have back pain.” Program leadership cannot do anything with that.

You want: “I cannot safely or sustainably do X, Y, and Z without flares that impair my functioning for 24–72 hours.”

Examples of functional limitations:

- Unable to stand >30–45 minutes continuously without moderate–severe pain increase.

- Unable to lift/push >25–30 lb repetitively.

- Severe pain flare with >2 consecutive nights of <4 hours sleep.

- Worsening neuropathic pain after 6–8 hours of continuous keyboard use without breaks.

Your treating clinician should help phrase this in their documentation. Your job is to translate that into work tasks.

5.2 Map Limitations → Specific Modifications

Do this in writing before any formal meeting.

For example:

Limitation:

- Standing >30–45 min → marked lumbar pain next day.

Modifications:

- Stool access and sit‑stand mix on rounds and in clinic.

- Scheduled 5‑minute stretch/position change every 60–90 minutes, built into workflow.

- Use of OR stools and table height adjustment where feasible.

Another:

Limitation:

- Multiple consecutive extended shifts (>14 hours) → multi-day pain spike, poor sleep, cognitive fog.

Modifications:

- No 24‑hour in house calls; convert to 16-hour max shifts where possible.

- Cap of 3 consecutive days >12 hours, followed by lighter day.

That mapping is what an ADA coordinator understands.

5.3 Who You Actually Talk To

Bad approach: casual hallway conversation with your PD.

Better structure:

- Treating clinician → detailed medical letter focusing on functional limits, not just diagnoses.

- University/hospital disability office or ADA coordinator → formal accommodation request.

- GME office + program director → interactive process meeting where you bring your pre‑mapped modifications.

Many residents skip step 2 and go straight to the PD. Then everything becomes informal, undocumented, and revocable on a whim. That is how people end up with “accommodations” that vanish the second leadership changes.

5.4 How Explicit You Should Be With Colleagues

You do not owe detailed medical disclosure to co-residents or faculty. But you will need some explanation for visible differences in schedule or work style.

Useful, brief script:

- “I have a chronic pain condition that occupational health is managing with some ergonomic and duty schedule changes. If you see me sitting during teaching or using the standing desk a lot, that is part of that plan.”

That usually shuts down gossip and sets a professional tone.

6. Specialty‑Specific Realities: What Is Flexible and What Is Not

Some residents get gaslit into thinking, “If you need accommodations, you chose the wrong specialty.” Occasionally true. Often lazy thinking.

Let me categorize roughly.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Cognitive/clinic-heavy (Psych, Rheum, Endo) | 90 |

| Mixed (IM, FM, Peds) | 70 |

| Procedure-heavy non-surgical (GI, Cards) | 55 |

| OR-intensive surgical fields | 30 |

6.1 High-Flexibility Fields

Psychiatry, neurology (with caveats), rheumatology, endocrinology, heme/onc, pathology, radiology.

These specialties:

- Have more predictable clinic or reading room time.

- Allow easier incorporation of ergonomic tech (sit‑stand desks, custom chairs).

- Can often tolerate significant duty-hour tailoring without patient safety issues.

If you are in these fields and being told, “We cannot possibly adjust your clinic schedule by 10%,” that is nonsense.

6.2 Middle-Flex Fields

Internal medicine, family med, pediatrics, emergency medicine, anesthesia.

Here, it depends heavily on program culture, rotation selection, and your exact pain pattern.

- IM/FM/Peds: wards and ICU months may be punishing, but you can lean on ambulatory blocks, consult services, electives, and mixed‑model rounds.

- EM: fixed-length shifts help, but overnight frequency and physical demands can be tough. Ergonomics in ED workstations is often neglected but highly modifiable.

- Anesthesia: a lot of standing and OR time, but also downtime periods, scope for stools, and team-based models.

Chronic pain is not an automatic disqualifier, but you need honest self‑assessment of what your body tolerates.

6.3 Low-Flex Fields

General surgery, neurosurgery, ortho, OB‑GYN (especially heavy OB programs), some IR.

There is no way around it: prolonged OR standing and physically demanding tasks are core, not peripheral. You can still have accommodations (stools, case distribution, duty‑hour tuning), but the core demands remain.

If you are early enough in training and already hitting an unsustainable wall with mandated OR time despite maximal accommodations, this may be a true “wrong-tool-for-the-job” scenario. That is harsh, but better faced in PGY‑1 than in year 5 after permanent damage.

7. The Hidden Risks: Overcompensation, Guilt, and “Makeup Work”

One of the nastier patterns I see:

- Resident gets formal accommodation: slightly reduced nights, more clinic.

- They feel guilty and start:

- Taking extra admissions “to show they are pulling their weight.”

- Picking up extra shifts “to prove they are not using the system.”

- Saying yes to every committee and teaching ask.

Within months, the pain condition is worse than before.

If you ask for accommodations, you must accept the logical consequence: your workload distribution will not be identical to your peers. You cannot then erase that difference by self‑imposed overwork.

You are not “cheating the system.” You are aligning your duties with your actual physiological capacity so you can still be practicing medicine in 10, 20, 30 years.

8. Future Directions: Where Residency Training Needs to Grow Up

Let me be candid: the fact that we are even having to do this as individualized warfare is a failure of the system.

A sane, modern residency model would:

Bake ergonomics into default design:

- Sit‑stand workstations on every ward.

- Reasonable step counts and walk distribution.

- OR stools and height adjustments considered standard, not special favors.

Normalize schedule flexibility:

- Not every resident needs the exact same call frequency to be “equally trained.”

- Objective case logs and competency assessments are more important than suffering-hours.

Integrate occupational medicine input into GME:

- Systematic screening for work‑exacerbated conditions.

- Early intervention before full-blown disability.

Recognize chronic pain as a legitimate disability domain:

- No more “But you look fine.”

- No more “We all have back pain; you just need to toughen up.”

We are not there yet. But you can still carve out a survivable path inside an imperfect system.

9. Putting It Together: A Sample Accommodation Package

To make this concrete, here is what a coherent, realistic plan for a PGY‑2 internal medicine resident with chronic lumbar disc disease and neuropathic leg pain might look like.

Functional limitations documented:

- Standing >30–45 min markedly increases pain.

- Prolonged walking (>10–12k steps daily) worsens symptoms for 24–48 hours.

- Sleep <4–5 hours for more than 1–2 consecutive nights triggers severe pain flare and cognitive slowing.

- Sitting without lumbar support >60–90 minutes increases axial pain.

Requested modifications (examples):

Ergonomic:

- Primary assignment to a height‑adjustable sit‑stand desk in main workroom.

- Provision of ergonomic chair with lumbar support and appropriately positioned external monitor/keyboard/mouse.

- Permission and cultural support to sit during teaching conferences, sign-out, and portions of rounds.

- Stool access during clinic visits and multidisciplinary rounds; permission to alternate sitting/standing during patient interactions when clinically appropriate.

Duty‑hour / Schedule:

- Elimination of 24‑hour in-house calls; substitution with a 16-hour night float system where feasible.

- Cap of three consecutive days with scheduled work >12 hours, followed by at least one day with ≤8 scheduled hours.

- Limitation to no more than two full night-float blocks per year, with protected recovery days before and after.

- Structured distribution of rotations with at least 50% of months on services with lower step counts and more seated work (clinic, consults, elective, daytime ICU with team-based cross-coverage).

Treatment access:

- Protected half-day every 2–4 weeks for PT and pain clinic, scheduled in advance and not deducted from vacation time.

This is a realistic, defendable package. It acknowledges essential functions (still doing nights, ICU, wards) but shapes them around a clearly documented condition.

10. Final Thoughts: Non‑Negotiables

Let me strip this down to the core.

Chronic pain in residency is not a personal failing. It is a medical reality that will either be accommodated intelligently or will silently wreck your body and career.

Ergonomic and duty‑hour modifications are not “special treatment.” They are legally supported, clinically rational adjustments that keep you safe and effective.

Vague complaints get vague help. Precise functional limits mapped to concrete modifications—documented through the formal ADA/disability channel—give you leverage and protect you from arbitrary reversals.

If you remember nothing else: you are not required to sacrifice your long‑term health on the altar of “looking tough” for 3–7 years. You are required to become a competent, safe physician. Smart ergonomic and scheduling choices are part of that competence, not an exception to it.