It’s late. You’re at your laptop with a half-written email to “Student Disability Services,” “GME Office,” or “Occupational Health.” You’ve rewritten the subject line five times. You finally got the courage to ask for extra time, a reduced call schedule, or a quiet testing room. You hit send.

You think you just sent your information to a neutral office that will treat it like HIPAA-protected gold.

Let me tell you what actually happens behind that screen.

The Myth: “Only Disability Services Sees This”

Every school and hospital loves to parade the same line:

“Your disability information is confidential and will not be shared with anyone who does not have a need to know.”

Sounds comforting. Very legal. Very safe.

But “need to know” is the crack in the wall. That phrase is where all the quiet power lives. Because who decides who “needs to know”? Not you.

I’m going to walk you through the real gatekeepers. The people you never see but who are absolutely shaping whether you get what you need—or get quietly stonewalled.

We’ll go level by level: students, then clinical rotations, then residency and boards.

Gatekeeper #1: The Disability/Accessibility Office… and Their Shadow Network

On paper, the disability office is your ally. They process documentation, decide what’s “reasonable,” and send out those one-sentence accommodation letters.

In reality, they’re the first filter. And they’re balancing three pressures at once:

- Legal risk

- Institutional politics

- “Burden” to the curriculum or program

I’ve been in meetings where the disability director literally said:

“We can’t approve that; the clerkship director will go crazy.”

They’re not supposed to think that way. But they do. Because they want to keep their relationships with powerful faculty intact.

Here’s who quietly influences them:

- General Counsel or the hospital/university lawyers

- Academic affairs / Dean’s office

- Program leadership (for residents/fellows)

- Testing coordinators / exam services

You think you’re negotiating with one person. You’re really facing a committee whose members you’ll never meet.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Disability Office | 95 |

| Dean/Academic Affairs | 70 |

| Program Director | 65 |

| Clerkship/Course Director | 60 |

| Legal Counsel | 55 |

That chart? That’s about how often each group actually touches or influences a request, based on what I’ve seen across multiple schools and GME programs. Disability office almost always. Legal counsel more often than they’ll admit.

How the disability office quietly limits your request

They rarely say, “We’re denying this because your program will be mad.” They translate it.

You’ll hear phrases like:

- “This would fundamentally alter the program.”

- “This goes beyond what is considered reasonable.”

- “We can only recommend, not require, that faculty implement X.”

Behind those phrases are emails you never see:

- “If we approve this, can your rotation still function?”

- “Would this create patient safety concerns?”

- “What precedent will this set for future residents/students?”

And here’s one of the more uncomfortable truths:

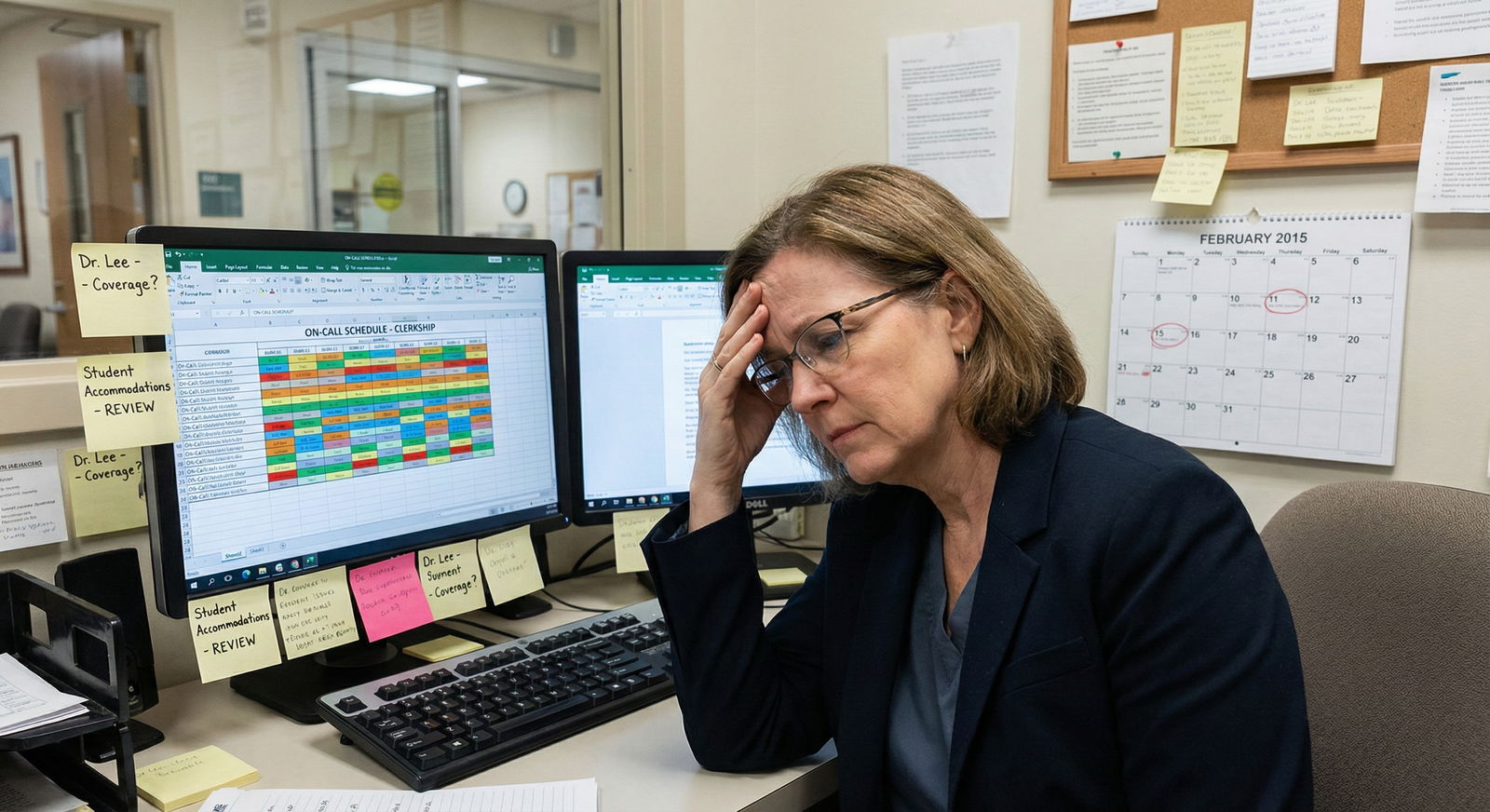

The more visible or disruptive your accommodation request is (schedule changes, call exemptions, shorter rotations), the more your fate shifts away from disability professionals and into the hands of training leadership—often without anyone saying that out loud.

Gatekeeper #2: Course and Clerkship Directors – The Local Weather System

Once your request moves from preclinicals into the clinical world, the climate changes fast.

On paper, the clerkship director just gets a one-line email:

“Student X is approved for testing in a reduced-distraction environment with 1.5x time.”

Or:

“Student X should have no overnight call.”

You’re told, “We don’t share the nature of your disability.” That part is mostly true.

But here’s what actually happens after that email lands.

The sorting in their head

Every clerkship director I know mentally sorts accommodated students into groups:

- “No big deal, easy to implement” – extra test time, quiet room

- “Mild pain, but fine” – excused from certain non-essential tasks

- “This will blow up my schedule” – call exemptions, lifting limits, timing changes

- “Potential patient safety problem” – anything that might affect speed, reliability, stamina

If your request is in the last two buckets, your experience depends heavily on that one person’s attitude toward disability and “fairness.”

I’ve watched this exact line said in a meeting:

“If I give this student no call, I’m punishing the rest of the team. That doesn’t feel right.”

That person now has to “implement” your accommodation. Their buy-in—or lack of it—decides whether you get quiet sabotage (bad evals, fewer opportunities) or genuine support.

And no, the disability office is not in the room when they vent about you.

Implementation vs. technical approval

Here’s the nasty split:

- Disability office controls approval

- Course/clerkship directors control implementation

So a school can claim, “We approved your request!” while a clerkship director slow-walks or half-implements it in the real world.

You see it as:

- “We couldn’t find a quiet room this week; try next exam.”

- “We’re short-staffed; we really need you on this call night.”

- “Everyone pulls long hours on surgery; it’s part of the culture.”

Those phrases are how “approved” accommodations die on the ground.

Gatekeeper #3: Program Directors – Residency’s Quiet Power Brokers

If you’re in residency or fellowship, the power shift is brutal.

Now your gatekeeper isn’t a dean. It’s your program director (PD). And they are balancing:

- Duty hour compliance

- Service coverage

- Morale of other residents

- Board pass rate

- Faculty pressure (“We need a strong person on this rotation”)

- Their own reputation as a “strong” or “soft” program

You file a request with GME or occupational health. It gets reviewed. Maybe legal looks. They send a determination.

Then the PD sits down and asks one question:

“How do I keep the wheels from coming off if I do this?”

And here’s what you usually never get told: they have far more discretion than you think.

I’ve seen PDs:

- Quietly block schedule changes by claiming “rotation requirements”

- Push residents with accommodations toward “lighter” but less career-advancing experiences

- Delay promotions under the pretext of “needing more data on performance”

- Tell faculty just enough that the resident starts getting treated like glass—or like a problem

The unofficial whisper network

You also need to understand the whisper network at the PD level.

Program directors talk. A lot more than anyone admits publicly.

If you’re applying for a transfer or fellowship with a history of accommodations, here’s the conversation that happens off the record:

“Hey, I heard your resident applied to us. Any concerns?”

“They did need some schedule adjustments for health reasons. Strong clinically, but we did have to tweak coverage a few times.”

“Oh. Got it. Thanks.”

That’s all it takes. Your application quietly moves into the “risk” pile.

No one will ever write “requested accommodations” in an email. But the concept—“stress tolerance,” “stamina,” “reliability”—gets smuggled in.

| Training Level | Formal Decider | Practical Gatekeeper | Biggest Quiet Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical MS1-2 | Disability Office | Course Director | Exam logistics & faculty attitude |

| Clinical MS3-4 | Disability Office | Clerkship Director | Schedule impact & team culture |

| Residency | GME/Occ Health | Program Director | Service coverage & PD bias |

| Boards/USMLE | Testing Agency | Test Center Staff | Local enforcement & documentation completeness |

Gatekeeper #4: Testing Agencies and “Independent” Boards

Let’s talk about Step exams, COMLEX, shelf exams, and specialty boards.

You deal with an online portal. You upload documentation. You get a decision email weeks or months later.

It feels mechanical and rule-based.

Behind that, there’s a layer of human gatekeeping you never see:

- External “independent” reviewers of your documentation

- Internal committees that worry constantly about “abuse” of accommodations

- Psychometricians obsessed with “score validity” and “comparability”

They won’t say that directly. They’ll talk instead about “insufficient evidence” or “diagnosis not adequately supported.”

But I’ve been in rooms where people said, verbatim:

“If we approve this level of time for every ADHD diagnosis, we’ll be buried.”

That’s the mindset you’re up against.

The real power: the documentation reviewers

Most applicants think:

“If I have a diagnosis, I get extra time.”

That’s not how they think. They look for:

- Objective testing (neuropsych, formal assessments)

- Functional impairment relative to peers at your level

- History of prior accommodations (undergrad, MCAT)

- Evidence that this is not “newly discovered” for the purpose of the exam

And here’s a less-discussed truth:

They are far more skeptical of requests that appear for the first time at a high-stakes exam with no prior paper trail.

So the real gatekeeper isn’t the faceless board. It’s the psychologist or disability specialist sitting with your packet asking, “Does this look like a genuine, longstanding disability or a last-minute strategy?”

, Functional impact unclear, Testing too old, Request too broad](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_svg/chart-common-reasons-high-stakes-exam-accommodations-are-7192.svg)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No prior accommodations | 80 |

| [Insufficient documentation](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/disability-accommodations/seven-documentation-errors-that-get-exam-accommodations-denied) | 75 |

| Functional impact unclear | 60 |

| Testing too old | 40 |

| Request too broad | 35 |

Those numbers mirror what internal training slides look like at some testing agencies. Not official public data. But very real.

Gatekeeper #5: The “Concerned” Faculty and Evaluators

There’s another group you probably don’t label as gatekeepers, but they absolutely are: the evaluators who decide whether you “meet expectations.”

A single attending or faculty member can’t directly grant or deny accommodations. But they can:

- Label you as “needing too much support”

- Call the clerkship office or PD with “concerns”

- Write performance narratives that quietly undercut you

A classic pattern I’ve seen:

You get an accommodation that modifies your schedule or tasks.

A faculty member notices. They don’t like it. They tell the director:

“I’m worried this student will struggle as an intern.”

Or

“I’m not sure they can handle the volume of a busy residency.”

That one comment becomes an entire storyline about you. Suddenly:

- Your “professionalism” gets watched more closely

- Your feedback gets harsher

- Doors start closing—away rotations, strong letters, chief resident consideration

The accommodation itself wasn’t denied. But the cost of using it gets raised so high that you start wondering if asking for help was a mistake.

That’s not paranoia. That’s how it actually plays out at a lot of places.

Gatekeeper #6: Institutional Culture – The Air You’re Breathing

There’s one more gatekeeper that doesn’t have a name tag but controls everything: culture.

Some places have decided—explicitly or implicitly—that disability accommodations are:

- A legal box to check, not a value

- A threat to “excellence”

- A problem that will multiply if they appear “too soft”

In those places, every human in the system feels that pressure. Disability office. Clerkship directors. PDs. Faculty.

So even when they technically follow the law, the underlying message is:

“We’ll comply, but we’re not happy about it. And you’ll feel that.”

In other institutions, leadership has drawn a hard line:

“We will accommodate. Period. We’ll solve the operational problems. We’ll not punish people for using legally protected rights.”

Those places exist. But they’re not the majority yet.

And nobody advertises which kind of place they are in their glossy recruiting material. You find out on the inside. Usually the hard way.

How To Navigate These Gatekeepers Without Burning Yourself

I’m not going to insult you with “advocate for yourself” and walk away. You already know you have to speak up.

What you need to understand are the levers that actually move things with these hidden gatekeepers.

1. Separate decision power from implementation power

Your question with any request should be:

- Who makes the formal decision?

- Who controls the day-to-day reality?

Because you may need very different strategies:

- For disability office: documentation, clarity, clean functional descriptions

- For clerkship/PD: framing, timing, making it clear you’re not trying to escape work, just to do it sustainably and safely

If you talk to a PD like they’re a judge, you’ll lose. They’re not. They’re a manager trying to keep a service running.

You are asking them to carry a burden for you. Whether they should or not is legally settled. Whether they will with any good will depends on how you present yourself.

2. Control your narrative before others write it

Harsh truth: if the only story out there about you is “the person with accommodations,” other people will fill in the blanks with their biases.

You need counter-narratives:

- Faculty who’ve seen you work effectively

- Objective performance data where you excelled

- A reputation for reliability within whatever structure you can safely work in

That does not mean you hide or “overcompensate.” It means you pick your advocates early and consciously.

One strong letter writer who knows the full story and still says, “This person is excellent,” can erase a lot of quiet suspicion downstream.

3. Consider timing and escalation like a chess game

If you escalate too early (straight to legal, formal grievances, public complaints), you might win the immediate battle but set off years of subtle retaliation or “concern” narratives.

If you never escalate, you get steamrolled.

So you pick your moments:

- Document quietly. Every delay. Every refusal. Every “we couldn’t find a room again.”

- Give the system a few chances to correct.

- When you escalate, do it with a clean record and specific patterns: “Over the last three exams, despite approved accommodations, X happened.”

The people above your local gatekeepers (deans, DIOs, HR, legal) are much more responsive to patterns than one-off complaints.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | You |

| Step 2 | Disability Office |

| Step 3 | Formal Approval |

| Step 4 | Course or Clerkship Director |

| Step 5 | Program Director |

| Step 6 | Faculty Evaluators |

| Step 7 | Testing Agency |

| Step 8 | Future Opportunities |

Look at that flow. Your entire future opportunities funnel through evaluators and test results, but the power play is happening two or three steps upstream.

The Future: Where This Is Actually Heading

There’s movement. Slowly.

Legal pressure, public conversations about physician burnout, and COVID’s long tail have forced institutions to rethink disability accommodations.

I see three trends building:

Centralized, more standardized accommodation policies at the GME level

Some large systems are pulling power away from individual PDs and making GME-wide accommodation rules. That’s good for consistency, bad if the system decides to be restrictive.Digital trails that institutions can’t ignore

Email threads, documented patterns of “approved but not implemented,” and internal surveys are starting to bite schools and programs in legal cases. They’re getting cautious.Generational change in leadership

More leaders with personal experience of chronic illness, mental health conditions, or disability are stepping into PD and dean roles. They’re not magically perfect. But they’re less likely to default to “this is weakness.”

The transition will be uneven. Some places will get worse before they get better, doubling down on gatekeeping because they’re afraid of being “flooded” with requests.

You’re in the middle of that shift. Not in a fantasy future where the system is fair. In the messy stretch where you have to understand the game to survive it.

FAQ

1. Should I disclose my specific diagnosis to my program or just rely on the disability office?

If you can get what you need through the disability office alone, keep the specifics there. Once you disclose a diagnosis directly to PDs or faculty, you can’t unring that bell, and it will color how they interpret every performance issue. Sometimes strategic partial disclosure (“I have a chronic health condition that affects X, and I’ve been formally approved for Y”) is enough. Full disclosure is a calculated risk, not a virtue test.

2. Will asking for accommodations hurt my chances for residency or fellowship?

Indirectly, it can—because of the way people tell stories about you, not because there’s a checkbox that marks you as “disabled.” Programs are not supposed to discriminate, and many do take that seriously. But informal backchannel comments about “reliability” or “stamina” absolutely happen. Your best countermeasure is strong performance when supported, plus at least one senior advocate who knows the situation and openly backs you.

3. What if my accommodations are approved, but my attendings keep ignoring them?

This is where you separate policy from practice. First, document every instance (dates, people, what was supposed to happen vs what did). Then go back to the disability office or GME with specifics: “On these three dates, this approved accommodation was not implemented.” You’re not complaining about personalities; you’re reporting non-compliance. If they still do nothing, that’s when you consider escalation to higher leadership or, in serious cases, outside counsel.

4. Is it better to wait and see if I struggle before requesting accommodations?

Waiting until you’re already failing or in crisis makes everything harder—on you, and on any reviewer trying to decide if this is a longstanding disability or a last-minute strategy. For high-stakes exams especially, late requests with no prior paper trail are scrutinized heavily. If you already know you have a condition that impacts your functioning, build the documentation and history early, even if you start with modest accommodations. You can always adjust later; retroactively rewriting your record is almost impossible.

Key points to carry with you:

- Your accommodation request passes through multiple invisible gatekeepers—approval is only half the battle; implementation lives with directors and faculty.

- People’s perceptions of you (reliability, “stamina,” professionalism) are the real currency in this system, and accommodations can distort those perceptions unless you manage your narrative and advocates.

- The game is changing, but not fast enough. You do not win by trusting blindly. You win by understanding who actually has power over your request at each step—and planning accordingly.