Visual Impairment in Clinical Training: EHR, Imaging, and Exam Workarounds

You are in a darkened reading room at 10:15 p.m., on your medicine sub‑I. The senior hands you a login for the hospital PACS and says, “Pull up the CT and walk us through.”

You lean toward the monitor. Crank the brightness. Blow it up to 400%. The text is readable. The images are… not. You can tell there is something in the right upper quadrant, but not whether that “something” is normal bowel, artifact, or the abscess the team is hunting for.

And you know this is not just a one‑off problem. It is the same with microscopic images in pathology lecture, subtle ST‑segment changes on EKGs, tiny EHR buttons, and the unreadable font of the shelf exam interface. You are not asking for an easier route. You are asking for a workable one.

Let me break this down specifically: what it looks like to train clinically with a visual impairment, and concrete workarounds for EHRs, imaging, and exams that I have seen actually function in real medical environments.

1. First Principles: What “Essential Functions” Really Are (and Are Not)

Before getting into tools, you need the framework. Because you will run into two phrases constantly:

- “Essential function of the rotation.”

- “Patient safety.”

Both get misused. Often.

The real questions are:

- What information do you need to perceive?

- Does it matter how you perceive it (vision only vs alternative modality)?

- How quickly and independently do you need to do it?

If an attending says, “You must identify lung nodules on a CT yourself with unaided vision,” that is not an “essential function of internal medicine.” That is one way to get to the essential function: clinical reasoning based on imaging information. Those are different things.

Same for EHR clicks. The essential function is: access and enter accurate data in a secure system, in a clinically appropriate timeframe. That does not require a mouse plus 20/20 vision.

You will be negotiating constantly around three domains:

- EHR and digital workflows

- Imaging and visually heavy data

- Exams and assessment formats

So let’s take them in turn. Not in theory. In very concrete detail.

2. EHR Workarounds: Turning a Visual Interface into a Usable Tool

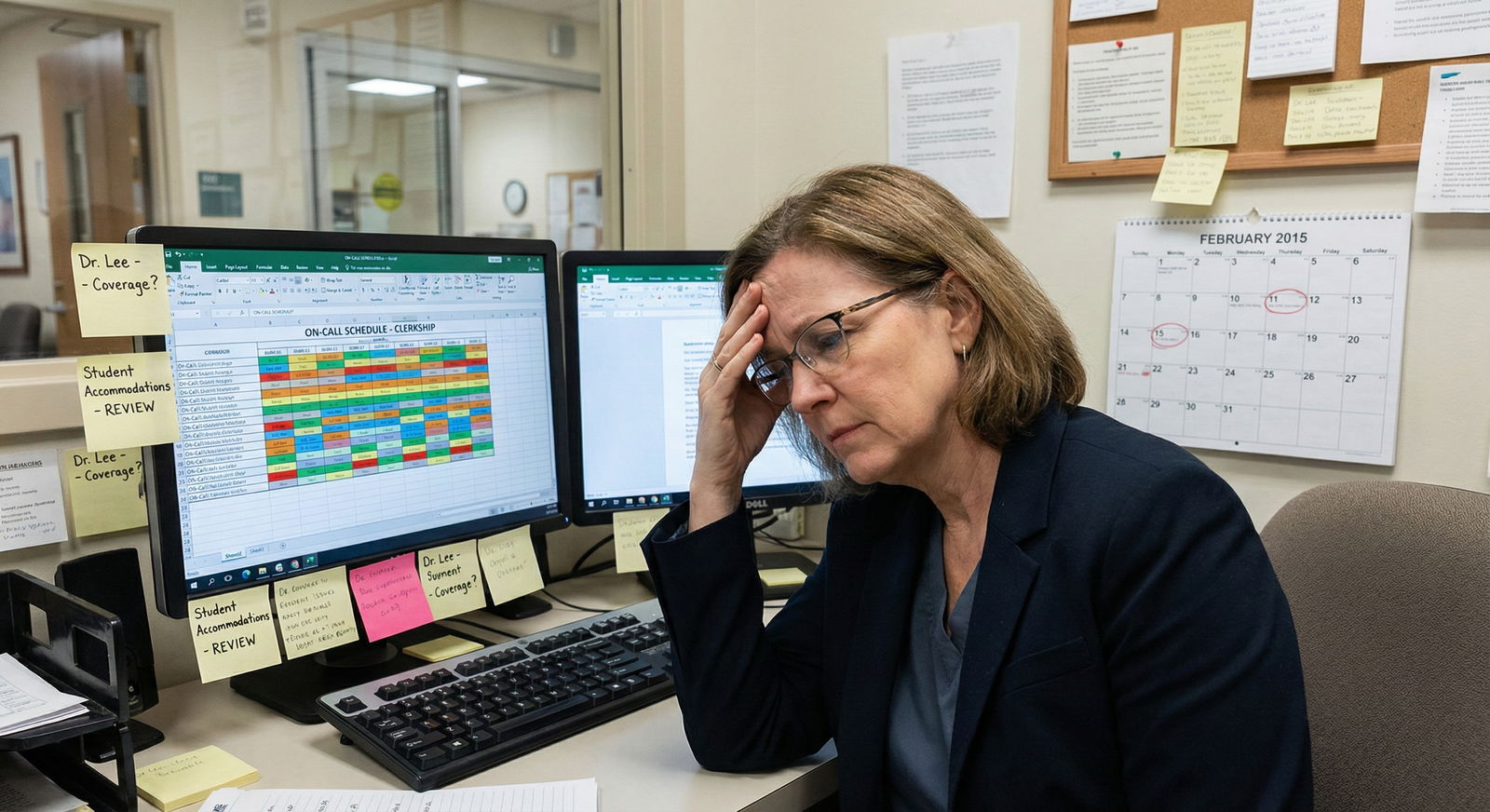

Modern EHRs are hostile to low vision by default. Tiny fonts, low‑contrast gray-on-gray buttons, pop‑up windows buried in corners, and mouse‑dependent workflows.

You are going to attack this on three levels: system settings, EHR‑specific tricks, and workflow redesign.

2.1 System‑Level: Making the Computer Itself Accessible

This is the foundation. Do not skip to EHR hacks if the OS is fighting you.

Common elements that work in clinical environments:

- High‑resolution monitors at larger physical size (24–32 inch displays are reasonable; 27+ is often best).

- OS‑level scaling to 150–250% (Windows Display Settings, macOS Display > Scaled).

- High‑contrast themes and system‑wide large fonts.

- Keyboard remapping to minimize mouse use.

For many trainees with low vision, the real workhorse is screen magnification combined with pointers and focus enhancements:

- Windows: Windows Magnifier, custom pointer size and color, text cursor indicator.

- macOS: Zoom, Display > Increase contrast, cursor size, smart invert.

If you use a screen reader (NVDA, JAWS, VoiceOver), your challenge is EHR compatibility. Epic and Cerner are not fully screen‑reader optimized, but pieces are usable with experience and some customization.

This part involves your disability office and IT. Do not let the school keep this at the “we’ll see what we can do later” stage. You need:

- A documented baseline accommodation: “Accessible workstation in each core clinical area with 27–32 inch monitor, OS‑level magnification, and keyboard shortcuts enabled.”

- A specific point person in clinical IT who knows your login and your settings.

No, you are not being “demanding.” You are making it possible to safely care for patients in the environment they chose (an EHR‑dominated one).

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Display scaling | 85 |

| High contrast mode | 60 |

| Large cursor | 70 |

| Screen magnifier | 75 |

| Screen reader | 40 |

(Values here are rough “percentage of low‑vision trainees I have seen actually using these,” not a formal study, but it reflects reality pretty well.)

2.2 EHR‑Specific Strategies: Epic and Friends

Epic is the most common beast, so I will focus there, but similar concepts apply to Cerner, Allscripts, etc.

Layout and Scaling

You want to minimize:

- Dense multi‑pane layouts

- Tiny flowsheet rows

- One‑pixel click targets

Concrete moves:

- Use Epic’s “Storyboard” and “Chart” view adjustments to increase font and zoom. Many instances allow user scaling; sometimes hidden in “Personalize” menus.

- Favor single‑pane views. For example, open notes full‑screen instead of side‑by‑side with orders if side‑by‑side shrinks everything unreadably.

- Pin commonly used tabs to avoid menu hunting.

If native zoom is not enough, combine with OS magnification. Many low‑vision trainees live at 150–175% OS zoom plus another 125–150% inside Epic.

Keyboard Shortcuts and Workflows

You want to reduce fine mouse tracking. Some concrete examples (Epic varies by institution, but patterns are similar):

- Alt+Tab or Ctrl+Tab to swap between open windows instead of clicking small tabs.

- Use patient search via keyboard (Ctrl+Space or dedicated hotkey) rather than clicking the small search bar with a mouse.

- For orders, type smart phrases or pre‑built order sets instead of browsing tiny lists.

Work with IT to:

- Set up favorite orders and order sets so you can type a few characters and hit Enter instead of scrolling.

- Build smartphrases for common note fragments (you do not want to re‑type ROS or PMH 10 times, and you definitely do not want to re‑scan for tiny bullet icons).

EHRs respond very well to short, repetitive text inputs. They respond badly to hunting with a cursor at 3x zoom.

2.3 Role and Workflow Adjustments

Some tasks are visually brutal and clinically trivial. Others are visually manageable but clinically central. You need to separate those.

Examples of adjustments that work without compromising training:

- Let another team member handle “checkbox reconciliation” of long med lists, while you dictate or verify verbally, and you handle the assessment and plan, orders, and clinical discussions.

- Swap roles on rounds: a sighted colleague “drives” the computer (open labs, images) while you lead verbal presentation, problem lists, and management reasoning.

- For discharge summaries, have a pre‑set template and do more dictation; let the team clerk or another student deal with visually dense med rec screens if they are tiny and poorly designed in your system.

None of this removes you from patient care. It simply assigns the visually gratuitous minutiae (clicking 2‑pixel scrollbars) to the person for whom that takes 0.3 seconds instead of 30.

| Task | Primary Tool | Who Can Own It Without Losing Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Entering long med list via tiny checkboxes | Mouse-heavy EHR | Sighted teammate with your oversight |

| Writing assessment and plan | Dictation + EHR | You |

| Navigating to imaging/labs on rounds | Mouse + keyboard | Sighted teammate |

| Reviewing trends and making decisions | Screen magnifier | You |

If a clerkship director claims that doing the clicking yourself is an “essential function,” push back. Calmly. With your disability office behind you. It is not.

3. Imaging: What Is Genuinely Workable and Where You Need Substitution

Imaging is where many programs get skittish. They often overestimate what you “must” be able to see alone, and underestimate how much of radiology and other image‑rich fields can be handled with nonvisual or lower‑vision workflows.

Let’s separate three different contexts:

- Using imaging as a consumer (every clinician)

- Being evaluated on basic interpretive skills

- Considering imaging‑heavy specialties

3.1 Using Imaging as a Consumer Clinician

Every clinician has to integrate imaging reports into care. You do not necessarily have to personally inspect every pixel of every study in detail.

What you need to access:

- Radiology reports: impressions, key findings, limitations.

- Critical images when needed: confirming that a line is in, getting a gestalt of a big effusion vs “clear.”

Workarounds that actually function:

- Text over pixels: Rely on formal reports as primary data and use imaging itself selectively. This is already how most internists, hospitalists, and surgeons practice; the “read” is the radiologist’s job.

- Large diagnostic monitors: For the rare times you really do want to look yourself, use the largest diagnostic display available (radiology reading room, OR PACS monitor) instead of a 13‑inch laptop on the ward.

- Adjusting window/level aggressively: Strong contrast adjustments often enhance faint structures into something you can actually see when combined with magnification. Radiologists do this constantly; you should too.

For someone with moderate low vision, being a consumer of imaging is usually workable with these adaptations. For someone with severe low vision or blindness, the role shifts more strongly toward report‑based decisions and verbal descriptions.

3.2 Educational Expectations: “Read This CXR” and Similar Moments

Medical education loves the “present the film” ritual. It also loves to pretend that catching a subtle pneumothorax on a portable CXR at 2 a.m. is a “core skill” for family medicine. It is not.

You will encounter multiple scenarios:

- “On rounds, tell us what the CXR shows.”

- “On exam, identify the fracture, effusion, etc.”

- “On OSCE, interpret this image real‑time.”

Concrete ways to handle each:

On Rounds / Informal Teaching

Be direct early in the clerkship:

- “I have a visual impairment and use magnification. For detailed reads, I rely more heavily on the written radiology report and verbal descriptions. I can walk through the implications; I just may not be the one to spot the 5‑mm nodule on the screen.”

Then offer an alternative that still demonstrates understanding:

- “Can we pull up the radiology report? I will summarize the key findings and then discuss how that changes our plan.”

You are still showing the essential function: clinical reasoning based on imaging data.

On Exams and OSCEs

These are higher stakes. You need accommodations documented before you walk in.

Typical adjustments that institutions can and do provide:

- Large‑format printouts of key images instead of tiny screen thumbnails.

- Extra time to allow zooming and panning.

- Ability to view images on a larger, adjustable monitor.

- Alternative format: providing a written radiology report instead of raw images for some questions, especially when the exam is testing management, not the raw act of reading.

I have seen schools shift an OSCE station from “Identify the fracture pattern on this tiny screen” to “Here is the formal radiology report describing the fracture. Counsel the patient on management and prognosis.” That is accommodation done right.

3.3 Imaging‑Dominant Specialties: Hard Truths and Creative Paths

Let me be blunt. If your central question is, “Can I be a teleradiologist reading 50 CTs an hour with severe low vision?”—probably not, at least not safely in our current visual‑only imaging ecosystem.

But the world is not binary. There are shades:

- Mild–moderate low vision: With large diagnostic monitors, aggressive zoom, high contrast, and time, I have seen trainees function reasonably well in limited radiologic interpretation settings. Speed is an issue; safety and self‑awareness become paramount.

- Severe low vision or blindness: Traditional image‑reading roles (radiology, dermatology focusing on pattern recognition, pathology microscopy) become very difficult. Here you are usually looking at roles where imaging is interpreted by others and you lead management, communication, or procedural aspects.

The frontier area—future of medicine, not fantasy—is machine vision and AI‑augmented imaging. Systems that:

- Flag suspicious regions and describe them textually.

- Provide verbal overlays of anatomical structures.

- Let you “tab through” labeled findings.

We are not there in clinical production systems yet. But research prototypes exist. If you are early in your training and are thinking long‑term, that is where I would aim advocacy and career niche building.

4. The Physical Exam: What You Must Adapt, What You Can Offload

Physical exam is where program directors start to get nervous. Again, often for the wrong reasons.

The core questions:

- Can you safely and effectively examine patients with modifications?

- Are there exam components where visual input can be substituted or minimized?

4.1 Systematic Triage of Exam Components

Break the physical exam down into:

- Nonvisual dominant: Cardiac auscultation, lung auscultation, abdominal palpation, many neurologic maneuvers, joint motion and palpation.

- Mixed visual/nonvisual: Edema assessment, JVP, some gait and posture evaluation, many rashes where texture and distribution matter.

- Purely visual or heavily visual: Subtle retinal changes on fundoscopic exam, tiny papules vs macules differentiation, reading fine print on med bottles, recognizing faint pallor or mild cyanosis at a distance.

You do not need to do every one of these personally to be a safe clinician. You do need reliable access to the information.

Workarounds I have seen work well:

Use tools that externalize the visual component:

- Handheld video otoscope/ophthalmoscope connected to a large screen you can see with magnification.

- Dermatoscopes connected to displays.

Team‑based exams: You perform and document the parts that rely more on palpation, auscultation, and history; a colleague or supervisor confirms or supplements heavily visual details on first few encounters or when critical.

Enhanced lighting and positioning: Many “I cannot see that” problems become “I can partially see that” with good overhead lighting, adjusted patient positioning, and choosing exam rooms with better visibility rather than cramped dim corners.

There is a difference between “I will never be able to interpret a retinal microaneurysm” and “I need a different tool and 10 more seconds.” Administrators like to conflate those.

4.2 Safety Boundaries and Disclosure

You must be honest with yourself and your team about what you cannot reliably see, especially when it affects safety. A few examples:

- You cannot reliably see subtle color differences in a fast‑moving environment (e.g., mild cyanosis, slight jaundice) even with magnification.

- You cannot safely perform needle‑guiding tasks that require fine depth perception beyond your capacity, unless you have adaptive tools (ultrasound with doppler audio, procedural aids).

When that’s the case, say it matter‑of‑factly:

- “I do not rely on my vision for subtle color changes; I prioritize vitals, perfusion by touch, and second opinions for borderline cases.”

- “I am not the right person to perform this particular procedure without ultrasound assistance.”

That is not weakness. That is good medicine.

5. Exams, Licensing, and Standardized Testing: Very Specific Tactics

USMLE, NBME shelf exams, OSCEs, board exams. These are where accommodations get rigid and bureaucratic. You win this by being extremely concrete and early.

5.1 What to Ask For, Specifically

There are repeat patterns that work for visually impaired candidates:

- Extra time (usually 50–100% additional) to allow for magnification, panning, and fatigue.

- Zoom and screen magnification tools allowed on the test workstation (or larger native font size).

- High‑contrast settings and color adjustments (if color vision is an issue).

- Separate room to minimize distractions since magnification often requires more eye movement and audio output if you use a screen reader.

For image‑heavy questions:

- On some exams, high‑resolution standalone versions of images.

- On others, textual descriptions as a substitute for questions where the core construct is not purely image interpretation (for example, management of a fracture when the question is really about anticoagulation, not about spotting the fracture itself).

You need your disability documentation to translate into test‑specific language:

- Instead of “needs more time due to visual impairment,” think “requires 50% extended time, permission to use 3x screen magnifier software, and access to 27‑inch monitor for all testing environments.”

5.2 Internal School Exams vs National Exams

Your school has more flexibility than NBME or USMLE. Use it.

For internal exams:

- Convert tiny-figure questions into large‑format, high‑contrast printouts or digital images.

- Replace some visual identification questions with case vignettes where the image is described verbally.

- Allow oral examinations for certain competencies (e.g., “walk me through your EKG interpretation process” while a faculty member reads the EKG verbally or uses a high‑res projection you can partially see).

For OSCEs:

- Standardized patients can provide verbal cues that substitute for small visual cues (“You notice a fine, erythematous rash on my chest”) if the competency being tested is communication or management, not dermatologic pattern recognition.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Pre-Clinical - 12-9 months before clerkships | Meet disability office, document needs |

| Pre-Clinical - 9-6 months before clerkships | Test EHR and exam accommodations locally |

| Pre-Clerkship - 6-3 months before start | Submit NBME/USMLE accommodation requests |

| Pre-Clerkship - 3-1 months before start | Meet clerkship directors, confirm workstation setups |

| During Clerkships - First week each rotation | Re-introduce needs to team, adjust workflows |

6. Future of Medicine: Where Technology Is Actually Moving in Your Favor

Let me be direct: you are training in a transition era. The current ecosystem was built assuming 20/20 vision staring at tiny rectangles for 12 hours. The next one will not be.

Several trends are your allies.

6.1 Voice and Natural Language Interfaces

EHR vendors are pushing ambient scribe tools, voice‑driven order entry, and conversational interfaces. This is not accessibility‑driven; it is burnout‑driven. But you benefit anyway.

What this means concretely:

- Placing orders by saying, “Order CBC, CMP, and PT/INR now” into a microphone rather than navigating through nested menus.

- Writing notes with ambient dictation that auto‑generates a draft you edit, rather than staring at a cramped template.

You should position yourself as an early and motivated user of these tools. They will make everyone’s life easier, but they turn your visual barrier into something largely irrelevant in certain tasks.

6.2 AI‑Augmented Imaging and Exam

This is not hype. It is just early.

We already have:

- AI overlays that detect pneumonia, pneumothorax, and nodules on chest radiographs.

- Computer‑assisted dermoscopy that flags suspicious lesions.

- Automated EKG interpretation that is at least a decent first‑pass.

The accessibility extension is straightforward:

- Instead of a faint highlight box alone, the system could say, “Region of concern in right upper lung field approximately 3 cm from apex, density consistent with consolidation, probability score 0.83.”

- For dermoscopy, “Asymmetric lesion, variegated pigmentation, irregular border, recommend biopsy.”

That is all just text and speech. Which scales for you.

You will probably still not be doing pure radiology reads. But you will be on more equal footing in specialties where imaging is one tool among many (EM, IM, cards, rheum, etc.).

7. Putting It All Together: How to Actually Navigate Training Year by Year

Theory is nice. Let me sketch what this looks like chronologically in a very practical way.

Pre‑Clinical (M1–M2)

You are learning systems, anatomy, pathology, and basic exam skills. Your friction points:

- Lecture slides with tiny text and microscopic histology images.

- Digital quizzes and midterms with small fonts and unlabeled images.

- Early physical exam labs with visual cues.

Your moves:

- Standardize your digital setup early: personal laptop / tablet with tested magnification, contrast, and annotation tools.

- Get disability office to enforce: accessible copies of lecture slides before class, not afterward; large‑print or high‑res exam materials; preferential seating where you can see any projected material.

- In skills labs, ask to use alternative tools: larger models, high‑contrast diagrams, and verbal cues from tutors.

Clinical Core (M3–M4)

Now you are in the hospital. This is where EHR and physical exam workarounds become daily life.

Your moves:

- Insist on a few dedicated accessible workstations on each major inpatient unit you rotate through. Not 1 in the basement. On the actual floor.

- Tell each team on day 1, in a low‑drama way: “I use large fonts and magnification on the computer. I work a bit slower in the EHR but will make up for it in [presentations, follow‑through, patient communication]. I may ask you to drive the mouse sometimes while I talk through the assessment.”

- Prepare standard lines for imaging: “I rely on the radiology report for fine detail, but here is how I interpret and act on it clinically.”

Residency and Beyond

Your real question here is fit. You can absolutely be a high‑performing resident with a visual impairment. I have seen it in:

- Internal medicine

- Psychiatry

- Pediatrics

- Family medicine

- PM&R

- Anesthesia (with some role scoping around specific visually intense procedures)

The path is the same, just with higher expectations and more autonomy:

- Negotiate role‑appropriate limitations (e.g., not being the primary line‑placer on a chaotic code if you cannot visually track needle tip positioning well, but taking charge of meds, timing, airway documentation).

- Leverage tech as it matures: speech‑driven documentation, AI‑assisted imaging, accessible monitors as baseline rather than “accommodations.”

Key Takeaways

The essential clinical functions are reasoning, communication, and safe decision‑making—not pixel‑perfect independent image reading or mouse acrobatics. Push conversations back to those essentials.

EHR and imaging barriers are often solvable with a layered approach: OS‑level accessibility, EHR customization, and workflow adjustments that shift visually gratuitous tasks without surrendering real learning.

Your future is not limited to “nonvisual” corners of medicine. With planned accommodations and smart use of evolving tech—voice interfaces, AI‑augmented imaging, accessible devices—you can practice broadly and safely. The system is slow to adapt, but it is moving in your direction.