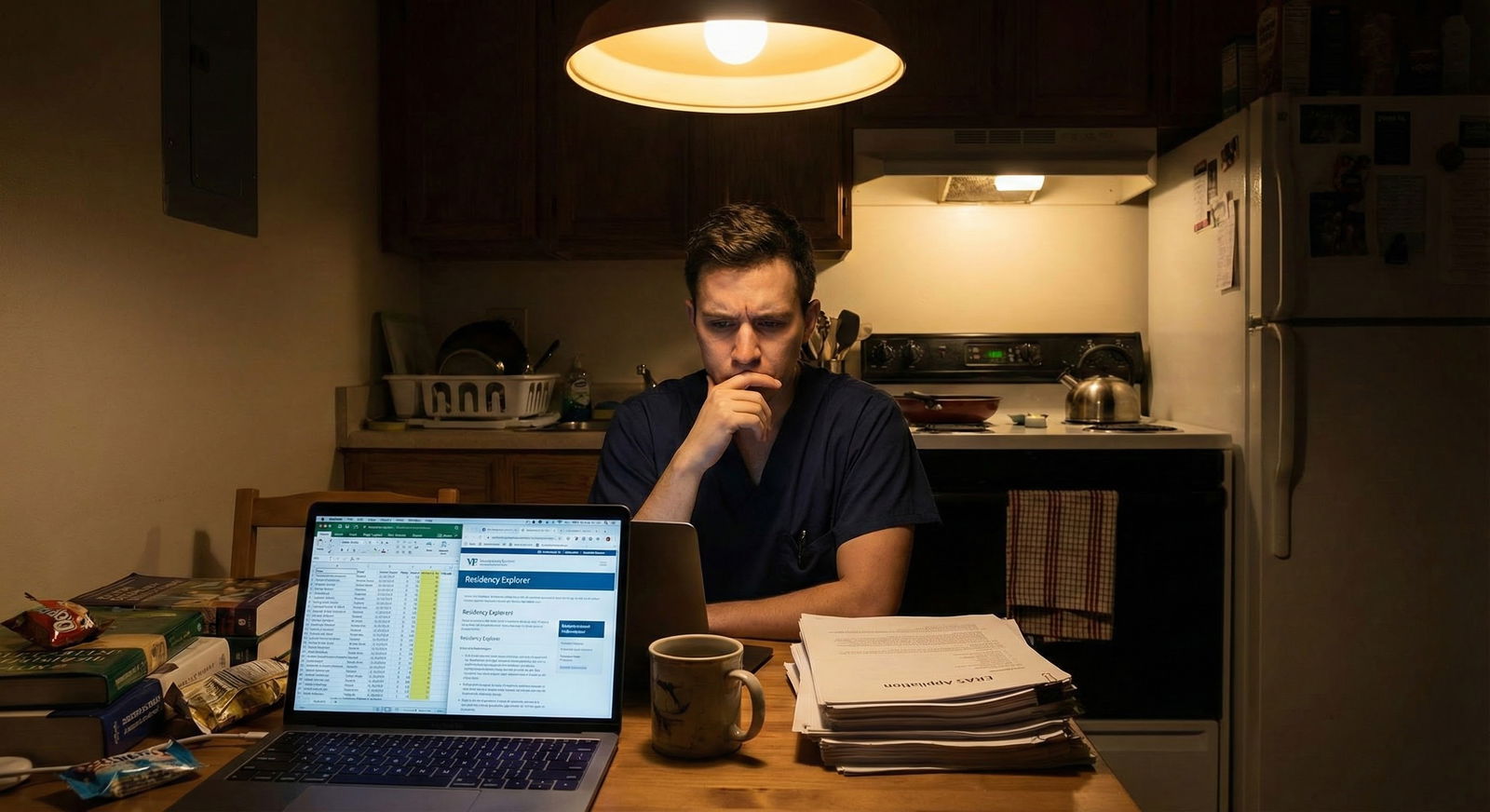

It’s late. You’ve got ERAS open, a spreadsheet full of programs, and this problem:

You’re 8–10 programs short of your “target number,” and most of what’s left are new, community, or “never-heard-of-that-place” residencies.

You’re asking yourself:

Do I pad my list with these newer or unproven programs… or is that just burning money and hope?

Here’s the answer you’re looking for.

Core Principle: New/Unproven Programs Are Tools, Not a Strategy

Let me be blunt:

New or unproven programs can be absolutely worth adding.

They can also be dead weight on your list.

The key is this:

They’re useful only if they increase your odds of interviewing and matching without meaningfully hurting your training, sanity, or career goals.

So your decision isn’t “Are new programs good or bad?”

Your decision is: Does this specific new/unproven program help me solve my specific match problem?

To answer that, you need three things:

- A realistic sense of your competitiveness

- A clear target number of programs

- A framework to sort “worth it” vs “skip it” among new/unproven programs

Let’s walk that through.

Step 1: Know If You Actually Need These Programs

Before you start padding, you need to know if you’re actually under-applied or just anxious.

Quick sanity check: are you under-applied?

Use this table as a rough guide for total number of applications (categorical only, not prelims/tying in advanced stuff). This assumes you’re not a superstar and not a raging red-flag case — just average-to-slightly-below-average for your specialty.

| Specialty Type | Relatively Safe Range | Higher-Risk Applicants |

|---|---|---|

| Less competitive (FM, IM, Psych, Peds) | 20–35 | 35–60 |

| Mid competitive (EM, OB/GYN, Anes, Neuro) | 30–45 | 45–70 |

| Competitive (Derm, Ortho, Plastics, ENT, Urology, NSGY) | 40–70 | 60–100+ |

If you’re already above the upper end of those ranges with legit programs, randomly stacking extra new/unproven ones is usually low-yield.

If you’re below or just barely at the low end of those ranges, then yes—new/unproven programs can help you safely reach your target count.

Step 2: What Counts as “New” or “Unproven”?

When you say “new” or “unproven,” you’re usually talking about one of these:

- Brand new ACGME-accredited programs (no graduating class yet)

- Recently expanded programs (suddenly doubled their class size)

- Community programs not affiliated with a big-name academic center

- Programs with:

- Almost no online footprint

- No reputation at your school

- Sparse or vague website information

- Few or no graduates in competitive fellowships

Not all of these are bad. But some are flashing warning signs.

Step 3: The 5-Question Filter for New/Unproven Programs

You don’t have time for deep-dive detective work on 30 borderline programs. Use a quick, repeatable filter.

If a program fails 2 or more of these questions badly, I’d think hard before adding it unless you’re very high risk for not matching.

1. Is it actually ACGME-accredited?

This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many people don’t check.

- Go to ACGME’s public website → verify the program is accredited

- Check if it’s Initial Accreditation vs Continued Accreditation

- Initial = newer, more unknowns

- Continued = established, at least somewhat vetted

If it’s not yet accredited or “applying for accreditation,” skip. You don’t gamble your career on that.

2. Who’s sponsoring it and what’s the hospital like?

Not all community hospitals are equal.

Look for:

- Sponsor is a known academic center or reputable health system (e.g., Mayo, Cleveland Clinic, Kaiser, big regional systems)

- Hospital has:

- ICU, ED, surgical subspecialties where appropriate

- Reasonable patient volume (check bed count, trauma level, service lines)

- Existing residencies or fellowships (a good sign they know what they’re doing)

If it’s a tiny hospital in the middle of nowhere with minimal services and no other GME, that’s riskier.

3. Is there any sign of structure or is it chaos?

On the website, see if they clearly show:

- Rotation schedules

- Educational structure (didactics, M&M, journal club, simulation)

- Faculty list with actual bios

- Clear leadership (PD, APD, core faculty)

No schedule, no clear curriculum, no faculty bios = often a bad omen. I’ve seen trainees end up at programs where “education” is an afterthought and service work dominates. That’s not what you want.

4. What’s the scut-to-education ratio likely to be?

New programs can skew one of two ways:

- Hidden gems: Highly motivated faculty, lots of support, excited to teach, strong case volume, residents treated well

- Workhorses: Residents are there mainly to plug cheap labor into call schedules and cover under-staffed services

Red flags:

- Job listings everywhere for the same hospital, especially for nocturnists/hospitalists covering services residents will now staff

- Vague descriptions like “fast-paced clinical environment” and “strong service orientation” with minimal mention of actual education

You won’t know everything from a website, but if the only concrete thing you can see is “busy hospital” and “new program,” be cautious.

5. Does this program align with your minimum non-negotiables?

You don’t need your dream program. But you do need a floor.

Know your minimum non-negotiables:

- Geographic: “I will not go to ___ region”

- Personal: partner job, kids, medical needs

- Career: you must have at least a chance at a fellowship, research, or academic path if that matters to you

If a program is in a place where you’d be miserable and trapped for 3–7 years, you’re not “increasing your odds”; you’re just moving the problem downstream.

When New/Unproven Programs Are Absolutely Worth Adding

There are very clear scenarios where these programs make sense.

1. You’re applying in a competitive or mid-competitive specialty with average or below-average stats

Example:

You’re applying Anesthesiology with Step 2 = 228, one fail on Step 1, and mediocre research. You’ve got 40 solid programs. Here, adding 10–15 newer/community programs that pass the basic safety checks is smart.

Why? Because:

- These programs are often less flooded with top applicants

- They may be more willing to look at applicants with bumps on the transcript

- They’re trying to build a reputation → more invested in attracting a mix of residents

2. You’re a reapplicant or have clear red flags

Failed previous match, exam failures, professionalism issues (hopefully resolved and well-documented) — you need volume plus forgiving programs.

Newer community programs often fit that description. They’re more likely to:

- Read past a single test failure

- Appreciate non-traditional backgrounds

- Be open to applicants schools quietly steer away from “top” programs

3. You’re region-flexible and lifestyle-focused over prestige

Some people just want:

- Decent training

- Kind colleagues

- A reasonable schedule

- A lower cost of living

In that case, a well-structured newer program in a smaller city can be a better fit than a toxic big-name powerhouse.

When New/Unproven Programs Usually Aren’t Worth It

Let’s flip it.

1. You’re already at or above a reasonable target number with solid options

If you have:

- 50+ decent IM programs

- 35+ EM programs

- 40+ OB/GYN/Anes/Neuro programs

…and most are established, reasonably known, and geographically acceptable, padding with 20 more “who even are these people?” programs rarely changes your outcome. You just burn money and headspace.

2. You need strong fellowship prospects in competitive subspecialties

Want GI, Cards, Heme/Onc, Ortho fellowships, etc.? A brand-new program with no graduates and no known fellowship placement record is a bigger gamble.

You can still match into fellowship from a new program, but the burden shifts to you to:

- Find mentors on your own

- Push for research opportunities

- Cold email programs for away rotations

If you already have better-established programs on your list, I’d only add truly unknown ones once your core list is solid.

3. The program looks like free labor with a residency label

If everything about the place screams:

- “We’re understaffed and desperate”

- “Residents will do everything… but here’s a free lunch”

- No mention of protected didactics, scholarly activity, or wellness

You’re gambling 3–7 years of your life for, at best, a mediocre training experience.

Decision Framework: Should I Add This Specific Program?

Use this 3-step quick filter on each new/unproven program:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Program is new or unknown |

| Step 2 | Skip unless strong other reason |

| Step 3 | Skip |

| Step 4 | Skip |

| Step 5 | Add as lower tier on list |

| Step 6 | Am I below a safe target number? |

| Step 7 | Meets safety basics - accredited, real hospital, some structure? |

| Step 8 | Violates my hard deal breakers? |

Translate that into how you build your list:

- Top tier: Strong academic or well-known community programs you’d be excited to attend

- Middle tier: Solid but less flashy programs, decent reputation, okay geography

- Bottom tier: Newer/unproven programs that are safe enough, not ideal, but you’d accept a spot there over not matching

You’re not pretending the bottom tier is amazing. You’re using it as insurance.

How Many New/Unproven Programs Should You Add?

Here’s a reasonable cap based on where you’re starting:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Already at safe range | 0 |

| Slightly below range | 5 |

| Well below range / high-risk | 10 |

Rule of thumb:

- If you’re already in the safe range: 0–3 max, and only if they genuinely look promising

- If you’re slightly below: 3–8 reasonable new/community programs or expansions

- If you’re well below OR high-risk applicant: 8–15 may be appropriate

Once you cross into “spray and pray” territory with 80–100+ applications in a non-ultra-competitive specialty, more isn’t smarter. It’s just noisy.

Don’t Ignore Cost and Burnout

Every time you add a program, you’re not just adding a line item fee. You’re adding:

- More interview invites to sort, rank, and schedule (if you’re lucky)

- More pre-interview prep

- More cognitive overhead deciding which interviews to attend

Application bloat is real. I’ve watched people apply to 80+ programs, get 20+ interviews they can’t even properly handle, and then complain that the process feels like chaos. It does. Because they made it chaos.

Anchor yourself: you’re adding targeted new/unproven programs to patch a gap. Not hoarding options out of fear.

Practical Example: Putting It All Together

Let’s walk one scenario.

You:

- Applying Internal Medicine

- Step 2: 221

- 1 remediation first year, no fail, solid current performance

- Regional school, low research output

- Target reasonably: 30–40 programs

You’ve identified:

- 25 solid, established IM programs in regions you’d accept

- 6 are “reach,” 14 are “realistic,” 5 are “safety-ish”

What now?

- You’re a bit below your ideal number.

- You pull 15 more options from ERAS → 10 are brand new or small community programs.

- You apply the 5-question filter:

- 4 look decent: accredited, real curriculum, connected to big health systems

- 3 are maybe-ok but not inspiring

- 3 are sketchy (no real info, tiny hospital, everything vague)

What I’d do:

- Add the 4 decent ones, maybe 1–2 of the “maybe-ok” if geography is good

- Skip the 3 that look like chaos

- End up with ~32–34 total applications

That’s a rational, defensible list.

Visual: Match Risk vs Program Quality Trade-Off

One more way to think about it:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Low Risk | 1 |

| Moderate Risk | 3 |

| High Risk | 5 |

As your match risk goes up (low stats, red flags, reapplicant, very competitive specialty), your willingness to tolerate less-proven programs should go up — but only down to your personal floor. Not below it.

FAQs

1. Is it better to go unmatched than match at a bad new program?

If by “bad” you mean unsafe training, toxic culture, or essentially zero education? Yes, sometimes not matching is better than being stuck somewhere that could wreck your mental health and career.

But that’s a small subset. Most new programs are not disasters; they’re just unknown and slightly disorganized. Those can be fine — especially if your alternative is not matching at all.

2. How do I spot a “hidden gem” new program?

Look for:

- Strong parent institution or health system

- Clear curriculum and rotation schedules online

- Faculty with legitimate backgrounds (trained at reputable places, some publications)

- Evidence of institutional support: simulation center, QI projects, GME office presence

If the program looks like “we’re new, but we’re serious,” that’s promising.

3. If a program has no fellowship match list yet, is that a dealbreaker?

Not automatically. They might not have any graduates yet. In that case, look at:

- Are there fellowships in-house?

- Are faculty connected to academic networks?

- Do they talk about supporting research or conference presentations?

If you’re fellowship-ambitious in a competitive field and have better options, prioritize those better-established places first.

4. Should I email new programs to gauge interest before applying?

You can, but don’t expect miracles. A short, professional email to the coordinator or PD asking about curriculum, volume, or fellowships is fine. Sometimes you’ll get a helpful reply that clarifies things. But don’t expect them to pre-offer interviews or promise anything; that’s rare and usually meaningless.

5. How do I rank new/unproven programs once I get interviews?

Same as any other:

- How did you feel on interview day?

- Do residents look exhausted or supported?

- Do they have a clear plan for your education?

- Can you see yourself living in that city for years?

Rank by where you’d actually want to train, not by age or prestige of the program alone. A well-run new program often beats a miserable old one.

Key Takeaways

- New or unproven programs can be very worth adding—but only as targeted, bottom-tier insurance to hit a rational application number, not as random list padding.

- Use a fast filter: must be accredited, have real structure, avoid your personal deal breakers, and not obviously treat residents as cheap labor.

- Know your risk level and your floor. Increase your tolerance for “unknowns” only as much as needed to reduce your risk of going unmatched—without throwing your training and sanity under the bus.