The usual “apply broadly and hope for the best” advice is lazy—and if you have a low score and no research, it can make you broke before it makes you a resident.

You cannot afford generic advice. You need a number. A strategy. And a hard ceiling on how much you spend.

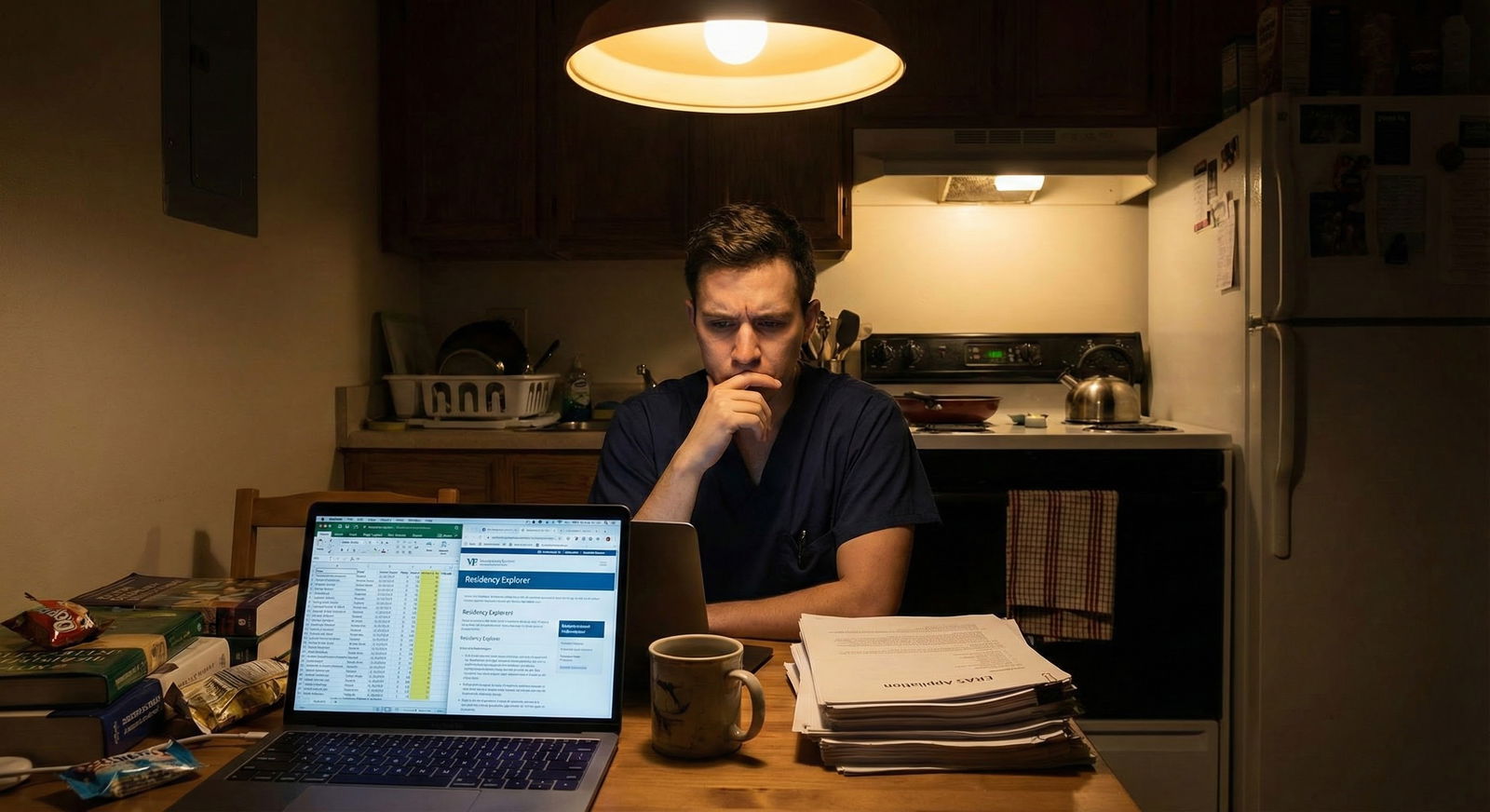

Let me walk you through this the way I walk panicked MS4s through it every year: step by step, specialty by specialty, with real numbers and actual cutoffs.

1. Reality check: where you actually stand

If you’re here, you’re probably in some version of this situation:

- Step 1: Pass (maybe on second attempt)

- Step 2 CK: 205–225 range, or below your specialty’s average

- Little or no research (maybe a poster, maybe nothing)

- Maybe a couple of red flags: LOA, repeat year, rocky clerkship comments

You’re not doomed. But you are not in the “apply to 30 programs and chill” tier. You are in the “strategy and volume matter” tier.

First distinction that changes everything:

- Are you applying to a non-competitive primary care field (FM, IM, peds, psych in some regions)?

- Or a competitive or research-heavy field (derm, ortho, ENT, ophtho, neurosurgery, radiation oncology, academic neurology, or higher-tier IM)?

If you’re in the second group with low scores and no research, you do not need a number of programs. You need a different specialty. Brutal but true.

So first, let’s anchor what “low score” looks like per specialty.

| Specialty Tier | Typical Matched Step 2 CK | “Low Score” Zone |

|---|---|---|

| Hyper-competitive (Derm, Ortho) | 250+ | <240 |

| Mid-competitive (EM, Anesth) | 240–250 | <235 |

| Standard IM/Peds/Psych | 230–240 | <225 |

| Family Medicine | 220–230 | <215 |

If your Step 2 CK is:

- ≥230 and you’re applying to IM, peds, psych, FM with no research: you’re “fine but unremarkable.”

- 215–229: now you’re in the “need to apply heavy and be thoughtful” group.

- <215 or multiple failures: this is red-flag territory; you must adjust expectations and target safety-heavy lists.

2. The money math: what you’re actually paying

You cannot answer “how many programs” if you do not see the bill.

ERAS charges escalate fast. Roughly (numbers vary by year, but this is the pattern):

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 20 | 349 |

| 40 | 786 |

| 60 | 1462 |

| 80 | 2210 |

| 100 | 3030 |

Then add:

- Transcripts, USMLE/COMLEX reports

- NRMP registration

- Interview travel (if in-person), or tech/attire/time for virtual

- Lost income if you miss work (for non-traditional / reapplicants)

Most students I’ve worked with blow their budget not on one big decision but on “just ten more” programs three times in a row.

You need to:

- Decide your absolute max spend before you touch ERAS.

- Back-calculate how many programs that buys you.

- Allocate that “budget” by tiers of program competitiveness.

Let’s say you cap yourself at $1,500 total for ERAS applications (not counting NRMP or exams). That usually buys you around 50–65 programs in a single specialty. If you dual-apply, each added specialty restarts the fee ladder.

If you’re thinking “I’ll just pay whatever it takes,” you’re setting yourself up to panic-spend later and still possibly not match.

3. Core principle: with a weak app, you need volume—but not random volume

Here’s the real rule:

Low score + no research = high volume, low delusion, high targeting.

That means:

- You apply to more programs than your stronger classmates.

- But you must be ruthless about excluding places that will never interview you.

Not every program is equally likely to consider you. Some are essentially auto-screens:

- Required Step 2 ≥ 230 in writing

- “Strong record of scholarly productivity required”

- “US grads only” if you’re an IMG

- “No prior exam failures” if you have a fail

If you submit to those, you’re lighting money on fire.

4. Concrete numbers: how many to apply by specialty and risk level

Let’s get to what you actually came for: ballpark program counts.

Assumptions:

- You’re a US MD/DO or a strong IMG with at least one US rotation.

- You have low-ish scores and no real research, but not catastrophic multiple failures.

- You’re okay matching in a less shiny location.

A. Family Medicine

FM is your best friend if scores are low and research is nonexistent.

Typical ranges I use:

- US MD with Step 2 ≥ 220, no research, no fails:

Apply to 18–30 programs if you have some geographic flexibility. - US DO or IMG, Step 2 215–225, or minor red flag:

Apply to 35–50 programs. - Step 2 < 215 or major red flag (LOA, repeat year):

Apply to 60–80+ programs, mostly community-heavy, non-academic, and in less competitive regions (Midwest, South, rural).

If you’re in the worst category and only want California FM, do not ask “how many programs.” The answer is: wrong strategy.

B. Internal Medicine

IM splits into two worlds: community / lower-tier university vs academic / university-heavy with research expectations.

If you have low scores and no research, we are talking community and lower-tier university IM, not top-30 research departments.

Typical ranges:

- US MD, Step 2 ≥ 225, no research, solid clinical evals:

Apply to 35–45 programs (avoid top academic places that list research explicitly). - US DO or IMG, Step 2 215–225, no research, maybe one fail:

Apply to 60–80 programs. - Step 2 < 215, IMG, or multiple fails:

Apply to 80–120 programs if financially possible, and strongly consider FM as a parallel.

If you’re aiming for a fellowship-heavy academic career and you have no research now, pick an IM program where they’re happy if you just do solid work. You can build your CV later; right now you just need to match.

C. Pediatrics

Very similar to IM, slightly more forgiving in some regions.

- US MD, Step 2 ≥ 225: 30–40 programs.

- US DO/IMG, Step 2 215–225: 50–70 programs.

- Step 2 < 215 or red flags: 70–90+ programs, heavy on community and lower-tier university.

D. Psychiatry

Psych used to be a safety net. It’s much tighter now.

- US MD, Step 2 ≥ 225, no research: 30–40 programs.

- US DO/IMG, Step 2 215–225, no research: 50–70 programs.

- <215 or major red flags: 70–100 programs, with serious consideration of FM or prelim years as backup.

Psych programs are increasingly picky about red flags, so don’t assume it’s easier than IM.

E. Emergency Medicine, Anesthesia, Neurology, etc.

With low scores + no research, these move out of “comfortable” and into “risky,” unless you have:

- Strong SLOEs (for EM)

- Very strong home support and networking

- No major red flags

If you insist on one of these with a weaker profile:

- Plan on 60–80+ programs minimum, plus:

- A backup specialty (FM or IM) with 30–40 programs

- Good advising on where you’re actually viable

If you’re not willing to do that, switch to a safer field now instead of paying for a disaster.

5. How to build a list without wasting half your budget

You do not build a list by scrolling ERAS and clicking like it’s online shopping.

You build it in layers:

Step 1: Clarify your risk category

Use this rough framework:

| Category | Profile Snapshot |

|---|---|

| Low-risk | Step 2 ≥ 235, no fails, decent evals, US MD |

| Moderate | Step 2 220–234, US DO or IMG, no major red flags |

| High-risk | Step 2 210–219, one fail, limited US experience |

| Very high | Step 2 < 210, multiple fails, IMG, or big red flags |

You’re probably Moderate to High. Act like it.

Step 2: Decide your specialty and backup

If you’re High or Very High risk and you’re still asking whether to apply to derm, ENT, ortho, etc., you’re not being honest with yourself.

Realistic paths:

- High-risk IM applicant → IM + FM backup

- High-risk Psych applicant → Psych + FM backup

- High-risk EM applicant → EM + IM or FM backup

If you can’t emotionally accept the backup specialty, that’s a different problem—but do not pretend it’s a “strategy” to ignore it.

Step 3: Use filters ruthlessly

On each program’s website (not just ERAS blurb), look for:

Red-flag phrases:

- “We require Step 2 CK of 230 or higher”

- “Significant scholarly activity expected”

- “No prior exam failures”

- “We do not sponsor visas” (if applicable)

- “We prefer students from top-tier schools” / heavy emphasis on research

These are easy cuts. Do not pay to apply there.

Then look for safer green flags:

- “We look at applications holistically”

- “We have no absolute cutoff”

- Large class sizes (more spots = more flexibility)

- Community-based, non-university programs

- Locations in less popular cities or rural areas

That’s where your money goes.

6. How to avoid going broke while still applying widely

You have two levers: number of specialties and number of programs per specialty.

If you have low scores and no research, here’s how I’d generally prioritize:

- One primary specialty you’d be content with, even if not your dream.

- Optional backup specialty if you’re high-risk.

- Strict cap on total spend → convert to total program number.

Sample scenarios

Scenario 1: US MD, Step 2 = 222, no research, wants IM

- Risk: Moderate.

- Target: Community-heavy IM, okay with non-coastal locations.

- Budget: ~$1,200 for ERAS.

Strategy:

- Apply to 45–55 IM programs that:

- Do not state hard 230+ cutoffs.

- Have at least a few DOs/IMGs in current residents (shows flexibility).

- Skip FM backup unless there are serious hidden red flags.

Scenario 2: US DO, Step 2 = 216, no research, one failed Step 1, wants Psych

- Risk: High.

- Budget: ~$1,500 for ERAS.

Strategy:

- Psych: 60–70 programs, including smaller and less popular states.

- FM backup: 25–30 programs you’d actually attend.

- Hard rule: no psych programs that publicly require Step 2 ≥ 230 or no failures.

Scenario 3: IMG, Step 2 = 212, no research, no US publications, wants IM

- Risk: Very High.

- Budget: ~$2,000 for ERAS (if realistic and affordable).

Strategy:

- IM: 90–120 programs in IMG-friendly areas, large class sizes, clearly listing current IMGs among residents.

- Strongly consider also 30–40 FM programs if financially possible.

- If that budget is impossible, you either:

- Postpone application a year to improve your profile, or

- Narrow to FM only with 60–80 programs.

7. Dual-application: when it’s smart, when it’s stupid

Dual-applying makes sense if:

- Your dream specialty is moderately risky,

- You genuinely would accept your backup specialty, and

- You can afford the added ERAS and interview costs.

It does not make sense if:

- Your primary specialty is wildly unrealistic with your scores (derm at 215),

- You’re just hoping for a miracle, or

- You plan to blow half your budget on long-shot applications.

Here’s the pattern I see that works:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Assess Risk |

| Step 2 | Pick Safer Backup Specialty |

| Step 3 | Single Specialty OK |

| Step 4 | Set Total Budget |

| Step 5 | Allocate 60 to 70 percent to Primary |

| Step 6 | Allocate 30 to 40 percent to Backup |

| Step 7 | Filter Out Unrealistic Programs |

| Step 8 | Submit ERAS |

| Step 9 | High or Very High? |

If your total budget only buys you, say, 60 applications total, I’d rather see:

- 60 carefully chosen programs in a single realistic specialty you’d be happy in

than:

- 30 long-shot dream programs + 30 half-hearted backups you didn’t research.

8. Small things that increase your odds (so you can apply to slightly fewer)

Since money is tight, you need every non-monetary edge:

Program signals / preference signaling (if your specialty uses them):

Use these on realistic stretch programs, not insane long shots.Home / affiliated program:

If your school has one, squeeze every bit of support, advocacy, and face time you can. A home interview is often your highest-yield.Geographic story:

If you have ties to an area (grew up there, family there, undergrad there), spell it out clearly in your application and sometimes in a short, targeted email to the PC later in the season.No generic personal statement nonsense:

If your app is weak on numbers, your PS cannot be a soulless “I have always wanted to help people” essay. It needs to be specific, reflective, and grounded in actual clinical experiences that show you’re mature and reliable.Clean letters:

A strong, specific letter from a clerkship director can offset a mediocre score way more than 10 extra random applications will.

9. Hard truths so you don’t sabotage yourself

Let me be blunt about a few patterns I see every year:

- If you blow half your budget on a specialty where you’re objectively non-competitive, you will often end up scrambling into a prelim or SOAPing into a field you didn’t plan on.

- If you refuse to consider FM or community IM because of “prestige,” you are choosing ego over matching.

- If you have serious exam failures and no research and no home support and you still apply only to California and New York, you are not unlucky when you don’t match. You were unrealistic.

You do not control your past scores. You do control how rationally you respond to them now.

FAQ (exactly 3 questions)

1. Is there any situation where applying to 100+ programs in one specialty actually makes sense?

Yes—if you’re high or very high risk (low Step 2, red flags, IMG) and applying to IM or FM, and you can afford it without wrecking your finances or your family’s. In that setting, sheer volume can dig out a handful of interviews, especially from smaller or IMG-heavy programs. But it only makes sense if you’re also being smart about where you apply (cutoffs, visa policies, class size) and you’re not splitting that budget across three unrealistic specialties.

2. Should I delay applying a year to strengthen my application instead of paying for tons of programs now?

If you’re in the very high-risk group (multiple failures, Step 2 below ~210, no US experience, no strong letters), delaying a year to improve—extra clinical work, dedicated US rotations, research, tutoring for better Step 3 if allowed—can be smarter than spending thousands on a near-impossible cycle. If, however, your profile is more “borderline” (low 220s, one minor red flag), I’d usually tell you to apply this year with a heavy but targeted list rather than losing a year of income and training.

3. How do I know when a program is truly out of reach versus just a stretch?

Out of reach is when the program’s stated requirements or resident profile directly conflict with your record: explicit 230+ cutoff when you have 215; “no prior failures” when you’ve failed Step 1; research-heavy academic powerhouse when you have zero scholarly work; 100 percent US MD current residents when you’re an IMG. Stretch is when your stats are slightly below typical but not disqualifying, and the program doesn’t have rigid rules posted. Aim maybe 10–20 percent of your applications at genuine stretches, and keep the rest solidly realistic.

Key takeaways:

- Low score + no research means you need more applications than average, but they must be targeted, not wishful.

- Decide your total budget first, then translate that into program numbers by risk level and specialty realism.

- If you’re in a high- or very-high-risk category, your best move is usually a realistic specialty choice + high-volume, filtered applications, not spraying dream programs and hoping for a miracle.