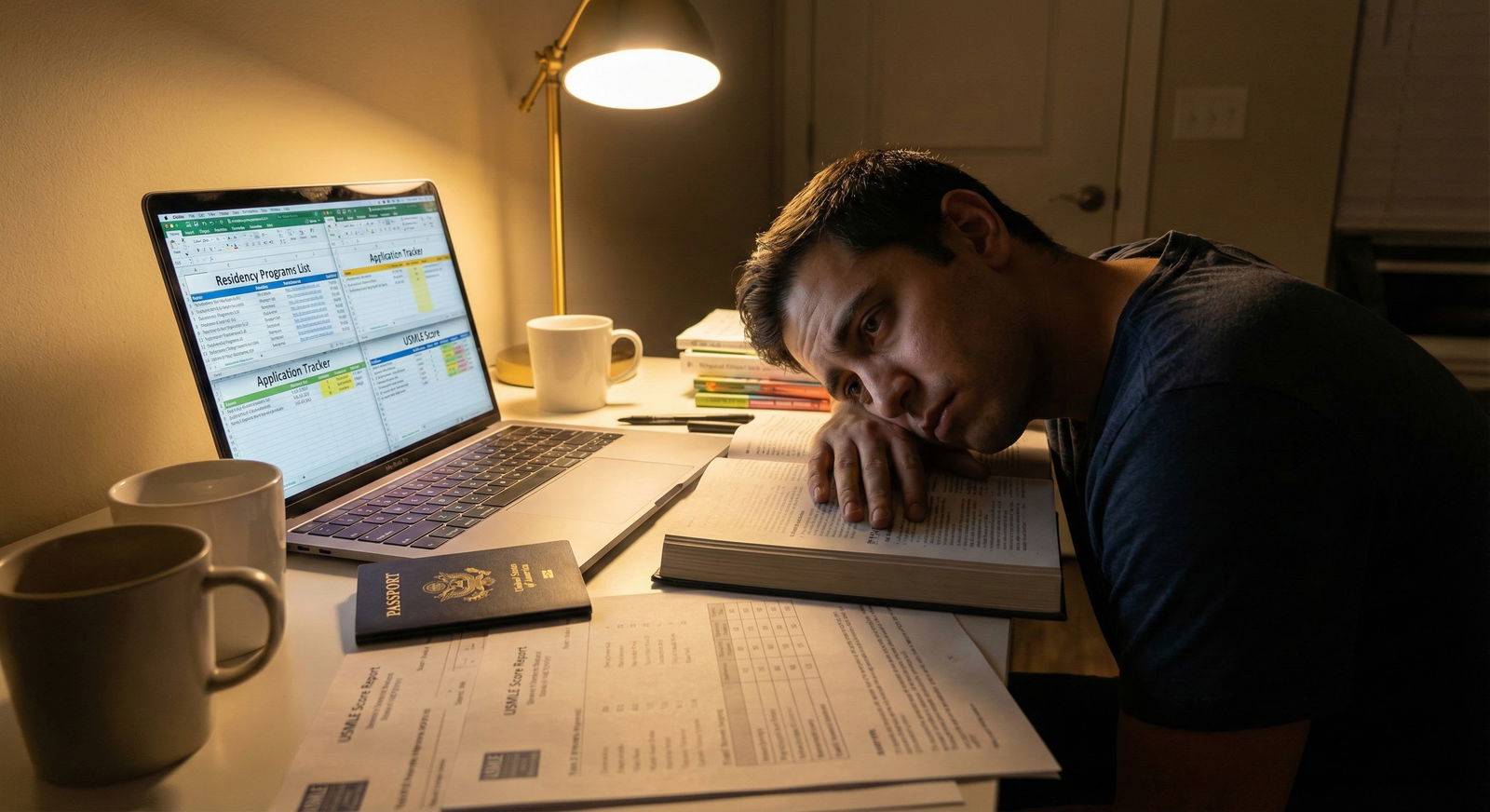

Last week, I closed my laptop after yet another webinar where everyone kept saying, “Lean on your mentors,” “Talk to your program director,” “Reach out to your home institution faculty.” I just sat there thinking: I don’t have any of that. No US mentor. No “home program.” No one to email. Just me, my ERAS login, and this awful sinking feeling that I’m walking into the Match completely alone.

If that’s you too, let’s just say it out loud: this feels rigged when you don’t have connections. It feels like everyone else had a head start and you’re still at the starting line, trying to decide if you should even run.

The ugly fear: is this whole thing doomed without connections?

Let me be brutally honest about where my brain goes on bad days:

– Programs want people they already know.

– People they “already know” are students from their med school or people referred by trusted colleagues.

– I’m neither. I’m not in the US. I’m not on anyone’s radar.

– So… what exactly am I supposed to do, send my application into a void and hope?

And every time someone says “network,” my stomach turns. Because “networking” sounds like this slick thing that US students do at grand rounds, or at in-person rotations, or though “my attending knows the PD here.” I have… none of that.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth I’ve had to swallow: connections do matter. People who say “connections don’t matter at all, just have a strong application” are either lying or delusional. I’ve seen too many stories where one email from a mentor turned a “maybe” into an interview.

But here’s the second truth that kept me from just giving up: “Connections” isn’t a binary. It’s not “either you have a famous US mentor who calls the PD for you or you’re dead.” It’s a spectrum. And you can move along that spectrum, from “literally no one knows I exist” to “some people in the US could realistically vouch for me.”

Not overnight. Not perfectly. But you’re not frozen where you are.

What “support network” actually means in the Match (not the fantasy version)

When people say “support network,” they make it sound like you need this massive entourage: mentors, sponsors, advisors, residents, coordinators, alumni, etc.

In reality, for an IMG applying to residency, you’re looking for four concrete things:

- Someone who can write you a meaningful letter or at least give you advice on your letters.

- Someone you can email with program questions without feeling like you’re bothering them.

- Someone who can occasionally say your name in a room you’re not in (or at least on an email list).

- People going through the same thing so you don’t fall apart mentally halfway through ERAS season.

That’s it. A “network” doesn’t have to be dozens of attendings who all know you deeply. Honestly, one or two real human beings plus a few weaker ties can change everything.

The problem is, as an IMG with no US mentors, not in the States yet, maybe still in home country or after graduation, you’re starting at 0.

So the scary question is: can you realistically build any of this from scratch, now, without a home program or a US school behind you?

Yes. But it’s going to look very different from the classic US med school version.

Let’s break it down.

Where IMGs without US contacts can actually meet people (for real, not theory)

Most advice for “networking” is vague and borderline useless: “go to conferences,” “be proactive,” “use LinkedIn.” Okay… and then what?

Here’s where I’ve actually seen IMGs start from nothing and end up with at least some support.

1. Online research or QI collaborations (low barrier, surprisingly effective)

This is one of the quietest, least-talked-about paths that actually works for IMGs abroad.

You look for:

– Faculty who publish a lot in your field of interest

– Especially those with multi-center studies or large resident teams

– People who’ve already taken IMGs on research or observerships (check their papers’ author lists)

Then you send a very specific, short, not-desperate email. Something like:

“Dear Dr. X,

I’m an IMG from [Country], interested in [Field]. I read your paper on [very specific topic] in [Journal] and was particularly interested in [one detail]. I have experience with [data entry / chart review / basic stats / literature reviews] and about [X] hours per week I can dedicate.

If you have any ongoing projects that need help with [specific task you can actually do], I’d be grateful for the chance to contribute remotely. I understand authorship is not guaranteed; my primary goal is to learn and help. I’ve attached my brief CV for context.

Thank you for considering this,

[Name]”

Will most people ignore you? Yes. That’s the part no one admits. Out of 30–40 emails, you might get 2–3 replies, and maybe 1 becomes something real.

But that one can turn into:

– A small research role → leads to a letter of recommendation

– A PI who knows your name → mentions you casually to colleagues

– A future observer- or externship opportunity if things go well

You don’t need 20. You need 1–2 who aren’t annoyed by you and see you as reliable.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Emails Sent | 40 |

| Any Replies | 6 |

| Actual Opportunities | 2 |

2. Social media, but used like a grown adult, not like a fan

X (Twitter), LinkedIn, sometimes Instagram – they’re ridiculously saturated with med content. But buried in there are real attendings and residents who actually respond to humans.

The mistake most of us make: we follow 200 people, like their posts silently for months, and then one day dump a huge DM asking for help, which they ignore.

What works better:

– Reply thoughtfully to a few posts from the same person over time. Not “great post,” but, “In [Country], we see [X] more than [Y] – do you approach that differently?”

– Share their content with a genuine comment, not tagging them 10 times like a spam bot.

– After a few interactions, send a short message: “I’ve appreciated your posts on [topic]. I’m an IMG planning to apply to [specialty] in [year]. Would it be okay if I asked you 2–3 questions about [very specific thing]?”

You’re not asking for a letter. Not asking for “Can you get me an interview?” You’re asking for tiny, specific help.

Some of them will:

– Offer to glance at your personal statement

– Answer questions about program tiers, visa-friendliness, or realistic application numbers

– Occasionally introduce you to someone else (“email our program coordinator and say I sent you”)

Is it guaranteed? No. But I’ve seen it happen enough times to say it’s not fantasy.

3. Residents and fellows from your country already in the US

This one hurts because it feels like begging your “people” for favors. But honestly, they’re often your best shot.

You look for:

– Alumni from your med school now in US residencies

– IMGs from your country in the specialties you’re eyeing

– People you can find through alumni groups, WhatsApp, Facebook, LinkedIn

You message like a human with limited time, not a bot:

“Hi Dr. Y, I’m [Name], [Year] grad from [School] in [Country]. I saw on [LinkedIn / alumni group] that you’re a [PGY-2 in X program]. I’m planning to apply to [field] in [year]. If you ever have 10 minutes, I’d love to ask how you approached programs and whether you think [X program type / visa options] are realistic for someone with [brief stats]. If now isn’t a good time, I completely understand.”

Stuff they can realistically help with:

– Which programs are actually IMG-friendly vs lip service

– How many programs to apply to with your stats

– What kind of red flags really mattered in their experience

– Whether their program likes people from your school/country

Sometimes they tell you to list them as “informal mentors” or will quietly mention you to chief residents or the PD. Sometimes they can’t. But your knowledge of the landscape improves a lot.

4. Observerships and short rotations: not magic, but not useless

If you can physically get to the US, even for 4–8 weeks, that’s where real, old-school mentorship can happen.

Yes, it’s expensive. And sometimes unfair. Some places charge ridiculous fees for basic observerships. But if you can do even one:

– Show up early. Always.

– Do the annoying tasks well: notes, follow-up calls, literature searching.

– Ask specific, short questions rather than babbling your entire life story.

– At the end, if things went well, say directly: “I’m applying to [field] and would be very grateful if you’d consider writing a letter. If you don’t feel you know me well enough, I completely understand – but I’ve really valued working with you.”

Not everyone will say yes. Some will dodge it. But again, you don’t need everyone. You need 1–2 who actually remember you when they open their email.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Observership |

| Step 2 | Show up early |

| Step 3 | Take initiative on small tasks |

| Step 4 | Ask focused questions |

| Step 5 | Ask for feedback |

| Step 6 | End of rotation |

| Step 7 | Request letter professionally |

| Step 8 | Stay polite, move on |

| Step 9 | Good rapport? |

The mental part: being “no one’s student” hurts more than anyone admits

What nobody talks about: when you don’t have a home program or US mentors, it’s not just a strategic disadvantage; it messes with your head.

You see US students talk about:

– “My PD advised me to…”

– “My faculty mentor suggested…”

– “Our Dean said our class should…”

And you’re just… not part of that. You’re on the outside of the whole ecosystem. It feels like trying to break into a party where you weren’t even invited, and everyone inside already knows each other.

So you start thinking:

– Maybe I’m not the kind of person programs want.

– Maybe if no one’s ever “adopted” me as a mentee, I’m not worth mentoring.

– Maybe my CV is just inherently behind and there’s no fixing it.

I wish I could give a magic phrase that makes that go away. There isn’t one. But here’s a harsher, truer perspective: the US medical education system is built around institutions. You’re not “less than” because no institution claimed you. You’re just outside their default pipeline.

The system’s not designed to find you. Which means you have to make yourself visible in annoying, awkward, sometimes humiliating ways. That doesn’t mean you’re begging. It means you’re hacking into a system that wasn’t built for you.

And honestly, that takes more grit than most US students will ever need.

How to reach out without feeling like a desperate spammer

My biggest fear every time I think of emailing anyone: “They’ll think I’m using them. Just another IMG wanting a letter.”

The line between persistence and pestering is real. Here’s how I try to stay on the right side of it:

Be painfully specific about what you want.

“Can you mentor me?” is vague and heavy.

“Could you look at my ERAS experiences section and tell me if it reads clearly?” is concrete.Show you value their time.

“I have 3 questions that would help a lot. They’re short and I can email them if that’s easier.”Accept “no” like a grown-up.

If they say they’re too busy, don’t try to convince them. Say thank you and walk away. The medical world is small; don’t become that name people warn each other about.Earn the next step.

If someone gives you advice and you use it, tell them. “I followed your suggestion about [X] and it helped me [Y]. Thank you.” That’s how you stop being “random IMG #437” and become “that person who actually follows through.”

| Type | Bad Message Snippet | Better Message Snippet |

|---|---|---|

| Subject | Need help URGENT | IMG applying to IM – 2 brief questions |

| First line | I am an IMG from [country] seeking opportunities | I read your post about IMG-friendly IM programs |

| Request | Please mentor me / get me an observership | Could you advise if [X type of program] fits my CV |

| Tone | Long life story, no clear ask | 1–2 sentences of context, 1 clear question |

Where to find emotional support when everyone around you “doesn’t get it”

Even if you manage to build some weak professional ties, it still feels lonely when your family and non-med friends think “you’re smart, you’ll be fine,” and don’t see the absolute chaos of the Match.

You need people who are also freaking out about:

– ERAS token emails

– Getting zero interview invites after 50+ applications

– Visa issues hanging over everything

– Time zone nightmares for virtual interviews

Some options that aren’t complete garbage:

– WhatsApp/Telegram groups for IMGs applying in your year and your specialty. Yes, they can get toxic. Mute them when needed, but having even 1–2 people to message when invites drop can keep you from spiraling.

– Discord servers / Reddit threads specifically for IMGs (filter hard; there’s a lot of noise, but occasionally real info and solidarity).

– A tiny accountability group: 2–3 people who share weekly goals (“finish PS,” “email X mentors,” “submit ERAS by [date]”) and check in, not just academically but mentally.

It’s not the same as having a PD who knows you. But it’s something. And something is way better than “I’m refreshing my email alone at 3 a.m. wondering if my life is over.”

The hard limits: what a late-built network can and can’t fix

I don’t want to lie to you: building a support network from zero, late in the game, will not magically erase:

– Low scores or many attempts

– Huge gaps in training

– Lack of US clinical experience

– Visa restrictions

Those things are real. Programs look at them. Connections can’t erase everything.

But a small, scrappy network can:

– Help you apply smarter (more realistic list, better strategy)

– Polish your application so you don’t waste your one shot looking unprepared

– Sometimes push your name just enough that someone opens your file instead of skimming past it

– Keep you from mentally disintegrating when the first batch of rejections shows up

I’ve seen IMGs with no original US mentors end up with:

– A research PI who wrote them a strong letter

– A resident who literally messaged them “Our PD saw your application today”

– A Twitter contact who forwarded their email to a program coordinator

– A random alumnus who did a 15-minute Zoom call that changed their rank list strategy

Is that “networking” in the glossy LinkedIn sense? No. It’s messy and uneven and half of it doesn’t work. But calling it impossible is just not true.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No network built | 25 |

| Weak network (1-2 mentors) | 45 |

| Moderate network (3-5 contacts) | 60 |

(Values here are illustrative, not official stats—but the pattern reflects what I’ve actually seen anecdotally: your odds improve meaningfully once even a few people know who you are.)

A brutally honest, doable plan for the next 30 days

If you’re still with me, here’s what I’d do if I were starting from absolutely nothing right now:

Week 1–2:

– Identify 20–30 faculty in your target field who:

– Publish decently often,

– Have IMGs on their papers or in their programs, or

– Work at IMG-friendly places.

– Send 5–7 carefully written, specific emails per week asking to help with something small and concrete. Track them in a simple spreadsheet.

Week 2–3:

– Clean up your LinkedIn/X profile so it doesn’t look like a ghost.

– Engage with 5–10 attendings or residents per week in a real way (thoughtful replies, not spam).

– Reach out to 3–5 alumni or countrymates in the US for a 10–15 minute call or email advice.

Week 3–4:

– Follow up ONCE, politely, with anyone who seemed friendly or interested but then went quiet.

– If you’ve built even a tiny connection, ask for one specific thing: advice on your PS, feedback on program list, or realistic opinion on your application profile.

– Join at least one IMG group (WhatsApp/Discord/etc.) where people are serious about the Match, not just complaining 24/7.

You’re not trying to create a “perfect” network by then. You’re trying to go from 0 to “at least 2–3 humans in the US would reply if I emailed them.”

That alone changes how alone this feels.

Here’s your next step, today: open a blank document and draft ONE email to ONE potential mentor or resident. Just one. Not perfect, not life-changing. Then send it. Stop reading about networking and create the first tiny thread of your own network, even if your hands are shaking while you type.