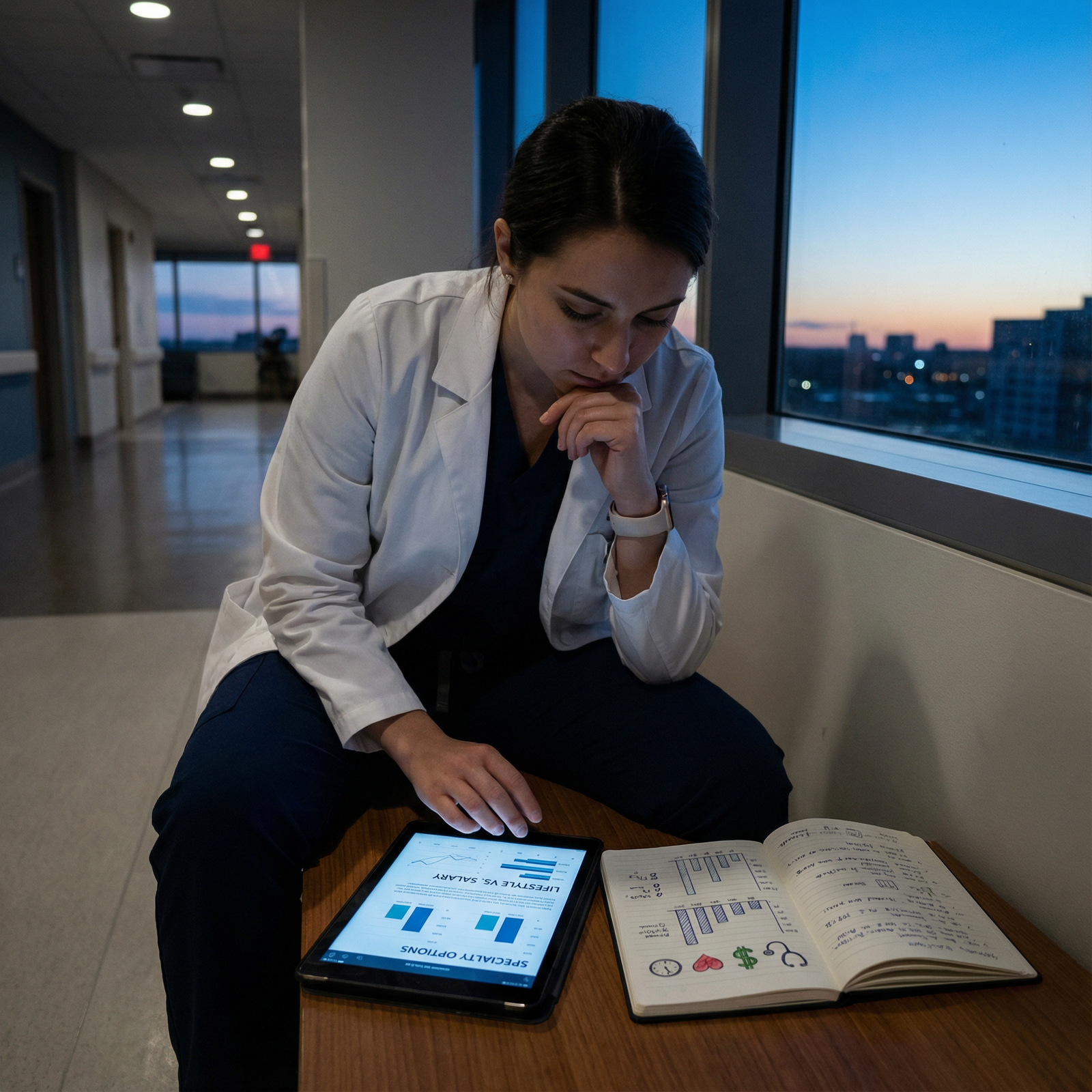

It’s 9:45 p.m. You just got home from a long evening shift as a pediatric resident. Your co-interns went for drinks; you went to daycare pickup, reheated leftover pasta, and negotiated a meltdown over the wrong color cup. Your loan balance is in the high 200s, your co-parent is exhausted, and you just did the math on an attending salary that’s… not anesthesia, not ortho, not derm. And you’re wondering:

Am I completely out of my mind trying to raise kids in training while heading into one of the lowest paid specialties?

You’re not. But you are in a high-risk situation — financially, emotionally, and logistically — if you go into it without a plan. Let’s build one.

1. Reality Check: What “Low-Paying Specialty” Actually Means For Your Family

We’re not talking about low income compared to the general population. We’re talking “low” compared to other physicians, and in the context of six-figure student loans, childcare costs that can rival a mortgage, and 60–80 hour workweeks.

Typical low-paying (relative) specialties where I see this most:

- Pediatrics (especially general peds, outpatient)

- Child psychiatry (better than peds, but not derm money)

- Family medicine

- General internal medicine (outpatient)

- Geriatrics, palliative care, adolescent medicine

- Academic tracks in any of the above

| Specialty | Common Range (Pre-tax) |

|---|---|

| General Pediatrics | $180k–$250k |

| Family Medicine | $200k–$260k |

| Outpatient IM | $210k–$280k |

| Child Psychiatry | $230k–$320k |

| Geriatrics | $200k–$260k |

Now add:

- Med school loans: $200k–$500k

- Childcare: $1,200–$3,000/month per kid (location dependent)

- Cost of living in typical academic centers: high

The real tension is this triangle:

- Your time is constrained by training.

- Your income is constrained by your specialty.

- Your kid-related expenses are not constrained at all.

You cannot fix this by “being frugal” alone. You need structural decisions: where you train, how your household is set up, what you say yes/no to in residency, and how aggressively you use the few financial levers you do have.

2. Before You Rank: Design Your Life, Then Your Rank List

If you’re still in the “about to start residency” or “ranking programs” phase, you have leverage. Use it. Most people do this backwards — they rank for prestige, then try to duct-tape a life on top. With kids and a low-paying specialty, that’s a mistake.

Step 1: Identify the non-negotiables for your family

Think specific:

- “Daycare drop-off must be possible by 7:00 a.m., not 8:00.”

- “We need to live within 20 minutes of both hospital and daycare.”

- “We need at least one grandparent or sibling within 30–60 minutes, or we need to afford backup childcare.”

- “My partner’s career cannot move, so I must stay within X city/region.”

Then rank programs not by name, but by this:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Proximity to family | 90 |

| Childcare options | 85 |

| Cost of living | 80 |

| Call schedule | 75 |

| Program prestige | 30 |

I’ve watched people match a “top” coastal peds program and spend 3 years drowning under $2,800/month daycare, insane rent, and zero family support — then quietly say later, “I’d pick the mid-tier Midwest program in a heartbeat if I could redo it.”

Step 2: Ask brutally specific questions on interview days

Hand-wavy “we’re family friendly” means nothing. You want receipts.

Ask current residents with kids:

- “Where do your kids go to daycare? How much per month?”

- “How often do you actually get denied vacation you asked for to attend kid-related events?”

- “On wards, what’s your real average weekly hours, not the brochure number?”

- “Is there a culture where people cover for each other when kids are sick, or do you get side-eyed?”

- “Do any residents have two kids? How are they doing? Be honest.”

Look for:

- Multiple residents with kids who are not visibly destroyed.

- Faculty who mention concrete policies, not vague “support.”

- PD who can tell you exactly how they handle parental leave, pumping schedules, clinic rescheduling.

Programs that shrug or “haven’t really had that come up” — that’s a red flag. You’ll be their pilot experiment. You do not want that job.

3. Childcare: The Single Hardest Operational Problem To Solve

This is where most dual medical–parenting disasters start. Not in the hospital. Not in the bank account. In the hour between 6:00 and 7:00 a.m. when daycare isn’t open and sign-out starts at 6:30.

You need coverage that matches reality, not fantasy.

Build a coverage map, not a single solution

Do this on paper. Literally draw it out. Something like:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Regular Weekdays |

| Step 2 | Daycare 7a-6p |

| Step 3 | Partner covers early am |

| Step 4 | Resident pickup post-shift |

| Step 5 | Nights |

| Step 6 | Partner solo or nanny |

| Step 7 | Grandparent if local |

| Step 8 | Weekends |

| Step 9 | Partner primary |

| Step 10 | Babysitter for post-call sleep |

| Step 11 | Kid Sick / Daycare Closed |

| Step 12 | Backup sitter / family |

| Step 13 | Resident uses sick or admin day |

You’re aiming for redundancy, not perfection.

Pieces you might combine:

- Daycare or preschool for core weekday hours

- Partner’s flexible schedule (if they have one; many do not)

- A regular babysitter or part-time nanny for early mornings / late evenings

- A grandparent or relative within driving distance

- Backup services (e.g., daycare’s emergency backup program or hospital-affiliated backup care)

The painful math: expect to spend real money here

If your post-tax pay as a resident is ~$3,500/month and childcare is $1,500–$2,000/month, that’s 40–60% of your take-home. It will feel wrong. You’ll question every decision.

But here’s the truth: trying to “save” money by patchworking unsafe, unreliable childcare will cost you more — in missed shifts, disciplinary issues, and marital implosion — than a solid plan. Childcare is not where you hunt for bargains.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Remaining Take-Home | 60 |

| Childcare Costs | 40 |

(A lot of people in high-COL cities are closer to 50/50. Still worth it. Training is temporary.)

4. Money Strategy When Your Ceiling Isn’t That High

You’re not going into ortho. You cannot count on brute-force income solving everything in the future. But you also don’t need to panic.

Here’s the playbook I push on residents in low-paying fields with kids.

Step 1: Get on the right loan plan early

Hospital orientation is not too early. You want:

- IDR (SAVE or similar) tied to resident income, not your med school zero-income year.

- Forgiveness strategy considered now, not 8 years in.

If you’re aiming for PSLF (common with academic peds/FM/IM):

- Make sure your residency hospital is a qualifying employer.

- Confirm HR actually reports your employment to fed servicer properly.

- Make qualifying payments every month, even if the amount is tiny.

Your low resident income means low payments now, which is an advantage later if you stick in nonprofit work.

Step 2: Stop feeling guilty about not paying big chunks of principal in training

I’ve watched residents torture themselves over not throwing $1,000/month at loans while literally paying for diapers and rent on 60-hour weeks. That’s self-sabotage.

During residency, your priorities:

- Make minimum required loan payments on the correct plan.

- Don’t rack up high-interest credit card debt.

- Keep a tiny emergency cushion (even $500–$1,000).

- Fund child-related essentials: safe housing, childcare, food, healthcare.

You are not in the wealth-building phase. You are in the “don’t dig deeper holes” phase.

Step 3: Make geographic choices that align with your specialty’s actual salary

Want to do outpatient peds or FM and also support two kids, plus loans, plus maybe a partner who doesn’t earn six figures? Then you probably cannot afford:

- SF Bay Area

- Manhattan / Brooklyn

- Downtown Boston / Seattle

- Popular mountain/ski resort towns with insane COL

At least not without making compromises (tiny housing, delaying more kids, co-parent working high-income job, etc).

A realistic move is this: choose residency in a mid-COL city similar to where you might want to practice. That way your partner can build career roots, you can build community, and you’re not constantly yo-yoing your kids across the country.

5. Shaping Your Schedule, Not Being Owned By It

You can’t magically make residency humane, but you can bend it in your direction more than you think — if you’re strategic and not apologetic.

Use the calendar offensively, not defensively

Before the academic year starts:

- Ask for the block schedule as soon as they’ll share it.

- Front-load the hardest rotations before/after late pregnancy if relevant.

- Cluster easier rotations when your partner has their busy season.

- Protect key dates: kindergarten orientation, big family events, end-of-pregnancy window.

Residents who ask early and specifically tend to get better outcomes. Residents who quietly “don’t want to be a bother” get whatever is left.

Learn to say a clean, unapologetic “no”

Examples:

- “I can’t add that extra clinic this week; I already have 6 days straight and I have childcare coverage only for that schedule.”

You’re not asking permission to exist. You’re giving facts. - “I’m happy to help with coverage next month, but this week I’m at childcare limit.”

- “I can present at grand rounds, but I can’t stay late to prepare slides every night. I’ll need a protected afternoon.”

Residents with kids who succeed are not the ones who never push back. They’re the ones who push back early, clearly, and professionally, instead of blowing up later from overload.

6. Protecting Your Relationship and Your Sanity

Plenty of residents without kids feel wrecked. With kids and low pay, the default path is “quiet resentment and constant exhaustion.” You can’t let the default run the show.

With your co-parent

Have the uncomfortable, practical conversation:

- “On wards months, assume I’m gone 6 a.m.–8 p.m. plus 1–2 weekend days. How do we handle mornings, evenings, and nights?”

- “If daycare calls that the kid has a fever at 2 p.m., who is primary? If that person truly can’t, what’s Plan B?”

- “What’s non-negotiable for each of us? Sleep minimums? Alone time? Workout time? Religious events? Family dinners?”

Then write it down. Not as a rigid contract, but as a baseline. When one person is a resident and the other is carrying 80–90% of the invisible labor at home, resentment builds fast if it’s not named.

With yourself

You will have guilt from both sides:

- Guilt for not being home enough.

- Guilt for not studying or “hustling” as hard as child-free colleagues.

You need to pick a direction: you are playing a long game. You are becoming an attending parent in a specialty you (presumably) care about. You are not competing with the PGY-2 who lives alone and does 3 extra research projects a year. Different sport.

Non-negotiables I suggest:

- Minimum sleep target (e.g., 6 hours) that you guard like a hawk on non-call nights.

- One small routine with your kid that almost always happens: 10-minute bedtime story, breakfast together on your post-call day, Saturday morning park.

- One block of time per week that is yours alone (even 45 minutes) where you aren’t a parent or a resident. Walk, coffee, sit in the car, whatever.

7. Career Moves Within Low-Paying Specialties To Improve Life

You picked a lower-paying specialty. That doesn’t mean every job inside it is equally painful financially or lifestyle-wise. Far from it.

Common levers:

- Location: Rural or smaller-city peds/FM/IM can pay significantly more than urban academic positions.

- Mix of work: A peds doc who does some urgent care shifts or moonlighting can add meaningful income. Same for FM docs doing hospitalist weeks.

- Partnership vs employed: In some areas, FM/IM private practice partners earn far better than academic attendings.

- Side interests: Teaching, admin roles, hospice medical direction, telehealth — these don’t replace your salary, but they can add $10–$40k/year later.

Just don’t try to build five side hustles during residency while raising toddlers. That’s how people explode. Focus on being competent, sane, and debt-stable first.

8. Special Case: Having a Baby During Residency in a Low-Paying Field

If you’re planning a pregnancy or adoption during training, timing and logistics can make or break you.

Pick your window, then engineer around it

More realistic approach:

- Aim for birth during or just before lighter rotations (outpatient, elective).

- Avoid due dates that land in the middle of ICU/wards months if you can.

- Know your program’s actual parental leave policy — and how it interacts with board requirements.

Then you set up:

- Coverage for late-pregnancy unpredictability (switching some calls, front-loading tougher months).

- A clear plan for leave, before you’re 30 weeks: who covers what, how makeups happen, how evaluations are handled.

Protect lactation and postpartum recovery like it’s a medical priority — because it is

Residents get into serious trouble trying to be heroes: back on wards 4 weeks post-cesarean, not pumping because it’s “too awkward,” ignoring their own depression.

Your lines:

- You will take the leave offered.

- You will insist on pumping-friendly schedules if you’re breastfeeding — blocked times, not “whenever there’s a moment” (because there never is).

- You will see your own doctor/therapist if you’re drowning.

The attending who says “back in my day we were on call 36 hours while in labor” is not your role model. That story is not a badge of honor; it’s an indictment of the system.

9. The Quiet Advantages You Actually Have

Let me be clear: money matters, and your specialty choice has real consequences. But raising kids in a low-paying field is not just suffering.

There are upsides you’ll only see years out:

- You will be absurdly good at triage: what matters, what doesn’t, what can wait.

- You’ll have realistic expectations of your future schedule. No bait-and-switch. Outpatient peds/FM/IM schedules, while not perfect, often allow decently family-friendly routines compared to some high-paid procedural fields.

- Your kids grow up with a parent whose work actually aligns with their values, not just their bank account. That matters more than you think.

And frankly, if you manage to raise functioning humans and become a solid peds/FM/IM/geri doc with this setup, you’ve already done something much harder than most of your colleagues who just chased RVUs.

10. Concrete 30-Day Action Plan If You’re Already In It

You’re not starting from scratch. You’re in the mess right now. So: next 30 days.

Week 1: Money

- Pull all loans into one simple spreadsheet: balance, rate, servicer, repayment plan.

- Verify your repayment plan and whether you’re on track for PSLF (if applicable).

- List every recurring expense. Identify the 2–3 biggest non-essential items. Adjust those first; do not nickel-and-dime coffee.

Week 2: Childcare and Backup Plans

- Map your regular week coverage and identify the “holes” (early mornings, late evenings, kid-sick days).

- Line up or at least locate one backup option: a sitter, neighbor, relative, or backup daycare program.

- Talk with your co-parent about a clear, default “who leaves work when daycare calls” plan.

Week 3: Program and Schedule

- Look at your next 6 months of rotations. Flag the hardest ones.

- Email chief or scheduler early about any must-cover family events or high-risk periods (surgery, due dates, partner travel).

- If you’re drowning already, schedule a meeting with your PD or APD to discuss schedule tweaks before something breaks.

Week 4: Your Sanity

- Pick one small weekly ritual with your kid(s) and guard it.

- Book one appointment for yourself: PCP, therapy, or just a haircut. Something that reminds your brain you still exist as a person.

- Decide one thing you will stop doing that is draining but non-essential: extra committee, side project, social obligation you hate.

You’re not fixing everything in a month. You’re turning the ship a few degrees. That’s usually all you can do in residency — and it’s enough to change where you end up.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Is it irresponsible to choose a low-paying specialty if I already have kids and big loans?

No, not if you go into it eyes open and make aligned choices elsewhere: location, lifestyle, housing, and childcare. Irresponsible is picking the specialty you hate just for money, burning out, and blowing up your life at 40. Many peds/FM/IM docs with kids do fine financially by choosing reasonable cities, using PSLF or long-term IDR strategies, and not inflating lifestyle too fast as attendings.

2. Should I delay having kids until after residency because of money and schedule?

From a pure logistics standpoint, sure, it’s easier later. But biology, age, relationship stability, and personal values matter more than “perfect timing.” I’ve seen residents who waited “for the right time” and ended up in fertility treatment hell during fellowship. If you and your partner want kids now and you can build a concrete support and financial plan, residency is survivable. Not pretty, but survivable.

3. Is it realistic to do part-time or 0.8 FTE in a low-paying specialty once I’m an attending and still afford kids?

In many markets, yes — if you avoid the very highest cost-of-living areas and are thoughtful about housing and debt. A 0.8 FTE FM or peds doc in a mid-COL city can often clear enough to cover a modest mortgage, childcare, and loan payments on an IDR plan. The key trade-off: smaller house, fewer luxury extras, but more time with your kids. For a lot of people that’s a very good deal.

4. How do I handle judgment from colleagues who think having kids in training is “selfish” or unprofessional?

You stop treating their opinion as relevant. People will always have something to say: you’re too focused on career, or too focused on family. The only scorecard that matters is whether your patients are cared for, your co-residents can rely on you, and your kids are safe and loved. Show up professionally, pull your weight, ask for accommodations early and transparently, and then mentally fire the armchair critics. They don’t live your life; they don’t get to design it.

With these pieces in place — money reality, childcare strategy, schedule control, and some guardrails around your sanity — you’re not just surviving a brutal season. You’re building the foundation for a long career and a real family life in a specialty you chose on purpose. As residency stabilizes and you move toward attending life, you’ll have a different set of levers to pull — partnership tracks, job offers, city choices. But that’s a fight for future you.