Perfectionism in anatomy and path is not a virtue. It is one of the most efficient ways to burn out bright students before they ever touch a real patient.

Let me break this down specifically, because the patterns are predictable. I have watched the same personality traits that produce beautiful anatomy scores and flawless path flashcards later fuel anxiety, imposter syndrome, and specialty choices driven by fear rather than genuine fit.

You are not “detail-oriented.” You are running a private, internal residency in self-criticism—with no days off and no attending supervision.

This article is about that: how perfectionism shows up in anatomy and pathology, how different specialties cultivate their own flavors of self-criticism, and what you can actually do about it without becoming sloppy or “okay with mediocrity” (the fear that keeps a lot of you stuck).

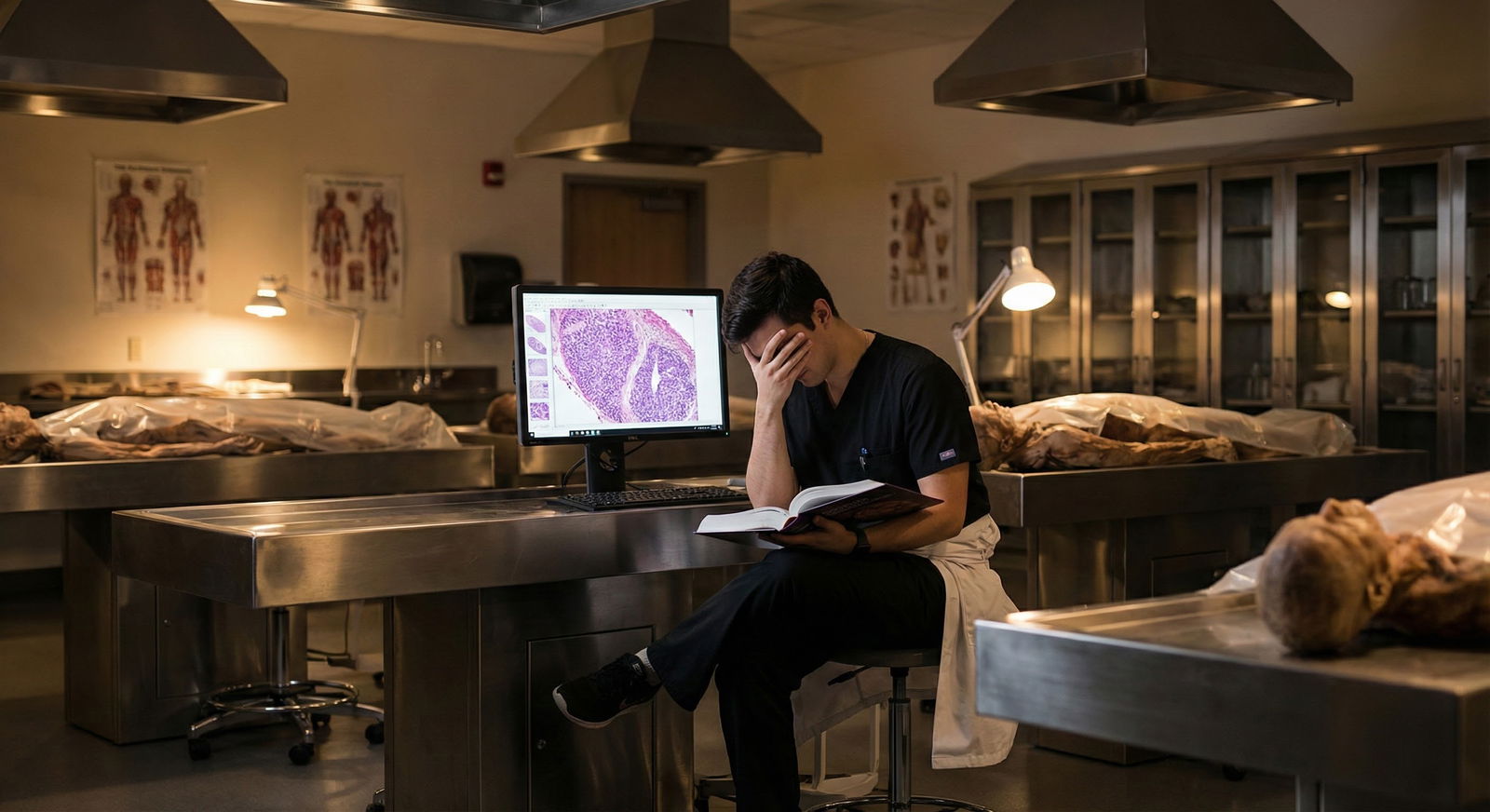

1. Why Anatomy and Path Attract — and Amplify — Perfectionists

Anatomy and pathology are where medical school quietly selects for perfectionism.

You get rewarded for it early:

- The anatomy practical where one missed branch of an artery costs you the A.

- The pathology exam with “two right answers” but only one “most correct” based on a single phrase in the stem.

- The lab sessions where other students ask you because “you always know the exact detail.”

The structure of these courses is tailor-made to pressure certain traits:

Binary right/wrong mindset

Either you know that nerve or you do not. Either you catch the key buzzword on path or you miss it. There is no partial credit for “good clinical judgment” in first-year anatomy.Microscopic focus, zero big-picture

You can spend three hours memorizing the branches of the SMA and never once talk about the patient with mesenteric ischemia. That disconnection feeds the belief that the only thing that matters is total recall.Public exposure of gaps

Anatomy lab pimping. Path lab quizzes on the spot. Everybody hears when you miss. That burns into your brain: “I must never be caught not knowing again.”

I have watched many first-years go from confident, thoughtful pre-meds to anxious checklists-on-legs by the end of the anatomy block. The trigger is rarely the workload. It is the type of evaluation and the culture around “knowing everything.”

You probably recognize at least one of these internal scripts:

- “If I miss a structure on the practical, I do not deserve to be a surgeon.”

- “If I cannot identify every glomerular pattern on histo, I am not cut out for medicine.”

- “If I get anything wrong on the lab quiz, the faculty will think I am lazy.”

None of that is rational. All of it is common.

2. The Anatomy–Pathway: How Perfectionism Evolves Across Training

Anatomy and pathology perfectionism does not stay confined to those courses. It mutates as you move from preclinical to clinical to specialty choice.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Anatomy & Path Courses |

| Step 2 | High-detail identity |

| Step 3 | Board-style thinking |

| Step 4 | Clerkship self-criticism |

| Step 5 | Specialty-driven perfectionism |

| Step 6 | Burnout or adaptation |

Here is the pattern I see over and over:

Phase 1: Identity forged in detail (M1/M2)

“I am the one who knows all the branches / patterns / histology.”

You start tying your worth to accuracy in micro-detail. The dopamine hit from nailing every structure is strong. You chase it.Phase 2: Transferring that to boards

Pathology becomes Step-style vignettes. You can get 80% of questions right with pattern recognition alone. So you double down: more Anki, more minutiae, more self-punishment when you miss a “stupid” detail.Phase 3: First clinical year collision (M3)

Real patients do not care that you know every intercostal muscle layer. Your attending cares if you thought of the right differential and did something safe. Perfectionist students feel lost: “The rules are fuzzy. I cannot get 100% on this.” Cue anxiety, over-prep for every case, rumination after rounds.Phase 4: Specialty flavor crystallizes

You start thinking, “What field matches the way I think?” Translation: “Where will my perfectionism be rewarded and not exposed?” That is where specialty-specific patterns of self-criticism show up.

Let us talk about those patterns.

3. Specialty Patterns of Self-Criticism: Who Thinks What

Different specialties attract different perfectionistic narratives. A lot of this starts in how you related to anatomy and path.

3.1 Surgery and Surgical Subspecialties: The Anatomy Absolutists

Surgical people often fell in love with anatomy. Or were very good at it and liked being known for that.

Their self-criticism has a sharp, unforgiving tone:

- “If I cannot visualize every step of this approach, I am unsafe.”

- “If I needed help finding a vessel, I am not cut out for OR.”

- “If the attending had to correct my anatomy, they will never trust me again.”

This typically starts early: in anatomy lab, these are the students who cannot tolerate getting a structure wrong at the tank. They go home and re-draw the brachial plexus ten times, not because it will help on exams, but because the shame of not knowing it lingers.

Later, in OR, it morphs into:

- Obsession with steps and “perfect case prep”

- Replay of every minor hesitation as “evidence I’m incompetent”

- Catastrophic thinking: one confused moment becomes “I should not be a surgeon”

The irony: the best surgeons I know had plenty of “I have no idea what that is” moments as residents. What differentiated them was curiosity and recovery, not omniscience.

3.2 Radiology: The Pathology Pattern-Seekers

Radiology is where pathology-style thinking reigns. Images instead of slides, but the same game: pattern recognition, subtle differences, “do not miss the tiny thing.”

Perfectionism here sounds like:

- “If I miss even one small incidental finding, I am dangerous.”

- “If I am not the first to see the abnormality, I am behind.”

- “If I cannot name every differential on the spot, I am a fraud.”

This often roots in path:

- Students who loved micro but hated talking to patients.

- People who got high UWorld path percentages and started to equate “spotting the pattern first” with worth.

In radiology reading rooms, I have watched residents quietly destroy themselves over a single missed tiny fracture they caught on retrospective review. Never mind that the clinical impact was minimal. The internal narrative: “I missed something. This proves I am bad.”

3.3 Internal Medicine: The “I Should Have Caught That” Generalists

Medicine pulls a lot of path-focused students who like systems and differential building. They may or may not have loved anatomy, but they almost always liked pathophysiology.

Their self-criticism is slower, more ruminative:

- “I should have recognized the pattern earlier.”

- “A good resident would have anticipated that decompensation.”

- “If I have to look this up, I am behind my peers.”

The link to path is the expectation of pattern mastery. They expect to see glomerulonephritis and immediately recall the exact classification, associated antibodies, and treatment. They do not forgive themselves for needing to check a guideline.

This gets reinforced on wards:

- Morning report that glorifies the one “zebra” diagnosis.

- Attendings who ask for the one rare association without acknowledging that 99% of the time it does not change management.

Students internalize: “Real doctors know everything from memory. If I do not, I am lesser.”

3.4 Neurology and Neurosurgery: The Mapping Purists

Neuro folks are often ex-anatomy geeks. They love pathways and networks. They think in maps.

Their self-criticism:

- “If I cannot localize this lesion perfectly, I am not a real neurologist.”

- “If I mix up tracts or nuclei during rounds, I am out of my depth.”

- “Anyone who needs an MRI to confirm localization is just faking it.”

This is straight from first-year neuroanatomy:

- Students used to drawing the homunculus, tracts, brainstem cross-sections.

- High reward for precise localization even when it does not change management.

On the wards, they beat themselves up when:

- They localize to the wrong side by one level.

- They need to look up a rare neurogenetic syndrome.

- The attending (usually someone who has seen thousands of these cases) “effortlessly” names a diagnosis.

3.5 Pathology: The Meta-Perfectionists

Pathologists carry the purest version of path perfectionism, unsurprisingly.

Their internal monologue:

- “If I miss a cell pattern, a patient might be misdiagnosed.”

- “If my frozen section call is wrong, I have failed the surgeon and the patient.”

- “I must see everything on the slide. Every time.”

Many path residents were the top scorers in path on Step exams. They were told, explicitly or implicitly, “You see what others miss.” That is flattering. It also sets up a brutal standard.

The result:

- Endless re-checking of slides long after a reasonable answer is reached.

- Reluctance to sign out cases without senior reassurance.

- Intense guilt over any amended report, even when the change is minor.

4. How Perfectionism Shows Up Day-to-Day: Concrete Scenarios

Let’s get specific. Here is how this actually looks in medical school life and exams.

Scenario 1: Anatomy Practical Fallout

You walk out of an anatomy practical. They tagged a tiny nerve branch you forgot existed. You still probably passed. But for the next 48 hours:

- You replay that one tag again and again.

- You do not remember the 30 items you got right.

- You tell yourself: “If this were the OR, I would have cut the wrong thing.”

What actually happened:

You missed a low-yield branch under time pressure on a cadaver with distorted anatomy. That says nothing about your future surgical performance. But your brain encodes it as a character flaw.

Scenario 2: Pathology Shelf Exam Spiral

During your path-heavy exam block, you miss a series of tricky questions. Post-exam, you:

- Re-open Pathoma or Robbins to “prove you were stupid.”

- Spend hours reading the exact paragraph whose nuance you missed.

- Conclude that “everyone else probably got that” and you are the only one who messed up.

You do not see the reality:

- Many of those questions are discrimination items designed to separate 245 from 255, not pass from fail.

- No attending will ever care that you misclassified one vasculitis for another on a preclinical exam.

But your path perfectionism frames it as: “If I do not nail every single nuance, I am not good enough for X specialty.”

Scenario 3: Clerkship Rounds with Anatomy Question

On surgery, the attending asks you to describe the blood supply of the stomach. You get 80% of it right but blank on one minor branch.

The attending shrugs and fills in the blank. Two minutes later, they have forgotten. You, however, are still thinking about it in bed at 2 a.m. and decide:

- “They now think I am unprepared.”

- “I embarrassed myself.”

- “A future surgeon should know this cold.”

What actually happened:

They saw a student who knew enough and will learn the rest later. But perfectionism converts a neutral moment into a career-defining indictment.

5. The Hidden Cost: Perfectionism vs Performance

Here is where I am going to be blunt: Perfectionism eventually makes you worse.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Low | 40 |

| Moderate | 85 |

| High | 70 |

| Extreme | 45 |

There is a sweet spot of conscientiousness:

- You care about accuracy.

- You check your work.

- You review what you miss and adjust.

Then there is what most medical students call “being thorough,” which is actually:

- Spending 3 hours on something that should take 45 minutes.

- Re-reading the same resource because anxiety, not knowledge, is driving you.

- Avoiding practice questions until you have “finished” all the content (you never will).

Concrete costs I see:

- Anatomy students who memorize every low-yield variant and still miss medium-yield structures because their cognitive bandwidth is shot.

- Path students who do 2,000 questions and yet do poorly on the shelf because they never practiced under timed conditions—they were too obsessed with getting each item right to simulate real conditions.

- Clerkship students who underperform because they spend the night before OR re-learning detailed anatomy instead of sleeping.

Your brain does not care how noble your intentions are. Sleep-deprived, stressed brains make worse decisions, recall less, and misinterpret feedback.

6. Specialty Comparison: How Perfectionism Plays Out

Let me lay this out side-by-side.

| Specialty | Core fear | Typical thought pattern | Common consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Making a visible, irreversible error | “If I miss one anatomical step, I am unsafe” | Over-prep, poor sleep, OR anxiety |

| Radiology | Missing a subtle finding | “If I do not see it first, I am incompetent” | Excessive re-checking, slow reads |

| Internal Med | Missing diagnostic pattern | “I should have caught that earlier” | Rumination, decision paralysis |

| Neurology/Neurosurg | Mislocalizing or mis-mapping | “If I cannot localize perfectly, I am a fraud” | Overstudying tracts, under-studying clinical impact |

| Pathology | Misclassifying disease | “If I miss a pattern, I failed the patient” | Avoiding autonomy, sign-out anxiety |

The point: your self-criticism is not random. It tends to align with:

- What you were praised for in anatomy and path.

- What your chosen (or target) specialty puts on a pedestal.

- Where evaluation is most opaque (you never get full feedback, so you fill the gap with blame).

7. Practical Strategies That Do Not Involve “Just Relax”

Let us make this actionable. You do not need generic wellness advice. You need targeted adjustments that respect your standards but stop the self-destruction.

7.1 Reframe What “Mastery” Means in Anatomy and Path

Right now, many of you define mastery as:

- “I can recall every branch, variant, or pattern without hesitation, in any order, under any condition.”

That is fantasy. Here is a better operational definition:

Anatomy mastery (student level): You can

- identify major structures and relations relevant to common procedures,

- anticipate common injury patterns,

- find what you forgot quickly in an atlas or app.

Path mastery (student level): You can

- recognize common patterns and their key differentials,

- connect mechanism to clinical picture,

- know which missing detail you need to look up to safely proceed.

Notice the key shift:

Mastery includes knowing how to look things up and what matters clinically. Not “I have every histologic pattern in my permanent memory.”

7.2 Use “Diagnostic Self-Criticism,” Not Global Self-Criticism

When you miss something in anatomy or path, your default is often:

- “I am stupid.”

- “I do not belong in this field.”

- “I am always missing obvious things.”

That is global, useless self-criticism.

Switch to diagnostic self-criticism:

- Ask: “What exactly broke down? Retrieval? Understanding? Attention? Fatigue? Time management?”

- Then: “What is the minimum adjustment that would have changed the outcome?”

Example:

- You missed a question on glomerulonephritis.

- Diagnostic breakdown: you recognized the pattern but forgot the specific serology.

- Minimum adjustment: “Review 1-page table of GN types 2–3 times this week,” not “Rewatch the entire 3-hour lecture.”

This preserves high standards while avoiding the spiral.

7.3 Set Explicit “Good Enough” Targets for Exams

If you do not set a ceiling, your brain will chase 100%. That is where a lot of the misery comes from.

For anatomy and path exams, define:

- Desired score range (e.g., “I am aiming for 80–90%.”)

- Acceptable miss pattern (e.g., “It is okay if I miss rare variants or zebras, not okay if I miss all of the core arteries or high-yield path patterns.”)

Before you start studying for a block, literally write:

- “I accept that I will miss: rare anatomic variants, obscure tumor subtypes, esoteric stain names.”

- “I will focus on: core vessel/nerve relationships, common tumor patterns, high-yield path mechanisms.”

You are training your brain not to treat every miss as proof of failure.

7.4 Distinguish Between Skill-Building and Ego-Protection

A lot of “extra studying” is not about patients or safety. It is about ego protection:

- You re-read the same Robbins chapter not because it adds new understanding, but because your fear decreases temporarily.

- You obsessively label every structure on a Netter plate, even those that never show up in exam questions, because it makes you feel in control.

Start asking:

- “Is this activity increasing my exam/clinical performance or just reducing my anxiety for an hour?”

- “If a classmate did what I am doing, would I call it smart or excessive?”

Be honest. Then start cutting 10–20% of purely anxiety-driven work and reallocate that time to sleep, exercise, or high-yield practice questions.

7.5 Build a Specialty-Specific “Reality File”

Perfectionism thrives on distorted comparison:

- You see the neuro attending who localizes in five seconds and assume they were born that way.

- You watch a PGY-5 surgeon tie perfect knots and assume you should be close as an MS3.

You need a counterweight. Build a mental (or literal) file of:

- Attendings/excerpts who openly discuss their own misses or gaps.

- Residents who admit, “I had to look that up.”

- Realistic performance standards at each level.

For example, in surgery:

- MS3: knows indication and rough steps of operation, key anatomy, asks good questions.

- Intern: can perform basic tasks, knows anatomy relevant to their tasks, recognizes complications. You are not expected to function like a chief resident in your third year. Stop grading yourself like one.

8. Protecting Mental Health Without Lowering Standards

This is medical school mental health, so let us be very direct about the stakes.

Perfectionism in anatomy and path sends many students into:

- Chronic anxiety.

- Sleep deprivation.

- Loss of joy in learning.

- Delayed or distorted specialty choice (“I cannot do X because I am not flawless.”)

You do not fix this by “caring less.” You fix it by:

- Caring differently.

- Using standards that map to actual clinical competence, not fantasy omniscience.

- Practicing self-criticism as a tool, not a weapon.

If you find yourself:

- Unable to sleep because you replay anatomy or path errors.

- Feeling dread before labs or OR days.

- Avoiding asking questions because you “should already know.”

That is not just “being driven.” That is a problem.

At that point, you need support:

- Talk to an upperclassman or resident in your desired specialty. Ask what is realistic at your stage.

- Use student health or counseling. You are not the first perfectionistic med student they have seen. Cognitive strategies for perfectionism are standard CBT fare.

- Loop in your advisor if your performance is starting to slip; perfectionism-driven burnout shows up as declining scores and motivation after an initial high.

FAQs

1. How do I know if my anatomy/path studying is “healthy” perfectionism or a problem?

Look at three markers: time, flexibility, and impact. Time: if you regularly spend more than 1.5–2x the recommended study time for the same content, that is a red flag. Flexibility: if you cannot switch strategies when something is not working because “I have to finish this resource perfectly,” that is rigidity, not dedication. Impact: if your sleep, mood, or relationships are consistently suffering, and your scores are not improving proportionally, your perfectionism is costing more than it is giving.

2. I want a very competitive specialty. Do I not need to be perfectionistic to match?

You need to be excellent, not perfectionistic. Those are different. Program directors want residents who are reliable, teachable, and resilient. A student who gets strong scores, learns from mistakes without imploding, and functions well in a team beats the brittle 260-scorer who melts down after any criticism. Competitive fields care about performance trends, letters, and how you act under pressure, not whether you never missed an anatomy tag in M1.

3. I feel behind because everyone else seems to know every detail in anatomy and path. Am I actually behind?

Probably not. You are seeing a distorted sample. The loudest students in lab and on group chats tend to be the ones who over-study details and perform showmanship. You do not see their anxiety or the hours they waste on low-yield minutiae. Compare yourself only to objective markers: practice exam percentiles, block grades, shelf scores. If those are in a reasonable range, you are not behind. You may just be less theatrically perfectionistic.

4. How can I talk about my perfectionism in residency interviews without sounding weak?

Frame it as a known trait you have actively managed. For example: “Early in medical school, I tended toward perfectionism, especially in anatomy and pathology. I used to catastrophize small mistakes. Over time, working with mentors and getting more clinical experience, I learned to separate high standards from unrealistic expectations. Now I use errors as specific feedback to adjust my studying and practice, without letting them paralyze me.” That shows insight, growth, and maturity—qualities program directors actually respect.

Key takeaways:

Anatomy and pathology are breeding grounds for destructive perfectionism because they reward microscopic accuracy and punish visible gaps. Different specialties then shape that perfectionism into predictable patterns of self-criticism—surgical, radiologic, medical, neuro, path. Your job is not to abandon high standards, but to redefine mastery, practice diagnostic (not global) self-criticism, and adopt study and thinking patterns that improve performance without sacrificing your mental health.